The Death of God: William Blake's Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blake's Re-Vision of Sentimentalism in the Four Zoas

ARTICLE “Tenderness & Love Not Uninspird”: Blake’s Re- Vision of Sentimentalism in The Four Zoas Justin Van Kleeck Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 39, Issue 2, Fall 2005, pp. 60-77 ARTICLES tion. Their attack often took a gendered form, for critics saw sentimentalism as a dividing force between the sexes that also created weak victims or crafty tyrants within the sexes. Blake points out these negative characteristics of sentimen "Tenderness & Love Not Uninspird": talism in mythological terms with his vision of the fragmen tation and fall of the Universal Man Albion into male and fe Blake's ReVision of Sentimentalism male parts, Zoas and Emanations. In the chaotic universe that in The Four Zoas results, sentimentalism is part of a "system" that perpetuates suffering in the fallen world, further dividing the sexes into their stereotypical roles. Although "feminine" sentimentality BY JUSTIN VAN KLEECK serves as a force for reunion and harmony, its connection with fallen nature and "vegetated" life in Blake's mythology turns it into a trap, at best a BandAid on the mortal wound of the fall. For Mercy has a human heart Pity would be no more, For Blake, mutual sympathy in the fallen world requires the Pity, a human face If we did not make somebody Poor: additional strength and guidance of inspired vision (initiating And Love, the human form divine, And Mercy no more could be, And Peace, the human dress. If all were as happy as we; a fiery Last Judgment) in order to become truly redemptive, William Blake, "The Divine Image" Blake, "The Human Abstract" effective rather than merely affective. -

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Poems and Fairy Tales Program (SCROLL)

Poems and Fairy Tales Anna Ball, soprano Annie Winkelman, oboe Lauren Winkelman, piano from Ten Blake Songs (1958) Ralph Vaughan Williams Infant Joy The Piper The Lamb The Divine Image Eternity In Sleep the World is Yours (2014) Lori Laitman Lullaby Yes Tragedy from Three Fairy Tales (1997) Marcia Kraus The Little Mermaid The Ugly Duckling Please join us outdoors for a reception following the performance. Wednesday, June 16, 2021 7:00 p.m. Knollwood Baptist Church www.knollwood.org/live Then every man, of every clime, Eternity Ten Blake Songs That prays in his distress, He who binds to himself a Joy poetry by William Blake Prays to the human form divine, Doth the wingèd life destroy; Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace. But he who kisses the Joy as it flies Infant Joy The Lamb Live in Eternity’s sunrise. "I have no name: Little Lamb, who made thee? And all must love the human form, In heathen, Turk, or Jew; I am but two days old." Dost thou know who made thee? The look of love alarms, Where Mercy, Love, and Pity dwell What shall I call thee? Gave thee life, and bid thee feed, Because it’s fill’d with fire; There God is dwelling too. "I happy am, By the stream and o’er the mead; But the look of soft deceit Joy is my name." Gave thee clothing of delight, Shall win the lover’s hire. Sweet joy befall thee! Softest clothing wooly, bright; Gave thee such a tender voice, Soft deceit and idleness, Pretty Joy! Making all the vales rejoice? These are beauty’s sweetest dress. -

Learner Resource 7 “The Divine Image” and “The Human Abstract” – a Comparison

William Blake Learner Resource 7 “The Divine Image” and “The Human Abstract” – a comparison In the exam you are asked to compare two poems. This activity poses the following exam-type question: • Explore how Blake presents religion in “The Divine Image” and “The Human Abstract”. You should consider his use of stylistic techniques, as well as any other relevant contexts. Below are two tables to help you to find ideas for your essay. Divide yourselves into pairs: one of you is responsible for completing table one and the other is responsible for completing table two. Once you have completed your half of the table, you can either take it in turns to give feedback to the class, or swap one of your completed tables with another pair, so that you have the two halves to refer to when you write your essay. Table one: “The Human Abstract” “The Divine Image” “The Human Abstract” Context: In the Songs of Innocence – rhetorical praise of God and man and the connections between them. Reference to the ballad form, and the common hymn metre. Possible links to “The Human Abstract”, “The Divine Image”. Structure: Introduction (human interaction with the abstract qualities of Mercy, Pity etc.), development (qualities seen in human behaviour and form), elaboration (unity of those qualities and God), conclusion (man, these qualities and God are one and the same – if we live by these qualities then we are close to God). Voice: First person plural, with the possessive pronoun “our” presuming a shared belief “our father dear”. Nature of the voice – declarative sentences suggest a confidence, that this is a statement of an accepted truth about the connection between man and God. -

The Symbol of Christ in the Poetry of William Blake

The symbol of Christ in the poetry of William Blake Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Nemanic, Gerald, 1941- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 01/10/2021 18:11:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/317898 THE SYMBOL OF CHRIST IN THE POETRY OF WILLIAM BLAKE Gerald Carl Neman!e A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the 3 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1965 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the. Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. APPROVAL. BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: TABLE OF COITENTS INTRODUCTION. -

“Did He Who Made the Lamb Make The… Tyger”?)

ARTICLE Blake actually identifies the question’s “thee” and indicates its addressee: it is not a tyger or, worse, a tiger,2 but “Tyger Tyger burning bright, / In the forests of the night.” In other words, he emphasizes his experienced poem’s self-referen- “Did he who made the Lamb tial character and, in effect, suggests the answer (or at least an answer) to its climactic question. Did he who made “The make the… Tyger”? Lamb” also make “Tyger Tyger burning bright”? Of course he did, because there is one and the same maker behind the two works—William Blake, who was perfectly aware of the By Eliza Borkowska provocation his work offered and who made it part of his artistic program aimed at “rouz[ing] the faculties to act.”3 Eliza Borkowska ([email protected]) is assis- Without doubt the self-referential element of “The Tyger” tant professor of English at the University of Social Sci- is Blake’s way to add more fuel to the fires of experience to ences and Humanities in Warsaw. She is the author of let them burn all the brighter. However, this self-referential But He Talked of the Temple of Man’s Body. Blake’s Rev- turn is not an independent act but a part of the program elation Un-Locked (2009), which studies Blake’s idiom as a whole, and it cannot be effectively performed before against rationalist philosophy of language. She is cur- an unprepared audience, on an unprepared stage. Let me rently working on her contribution to The Reception therefore return to it later, at a more mature stage of this of William Blake in Europe, writing her second book reflection, after I explain how I understand the idea of this (The Presence of the Absence: Wordsworth’s Discourses on performance. -

The Divine Image Jocelyn Hagen Pdf - $1.75 Treble Choir, SSATB, Oboe, Piano Printed - $3.25 JH - C002

The Divine Image Jocelyn Hagen pdf - $1.75 treble choir, SSATB, oboe, piano printed - $3.25 JH - C002 The Divine Image Treble choir, SSATB choir, oboe and piano The Divine Image by William Blake _________________________________________ To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love, All pray in their distress, And to these virtues of delight Return their thankfulness. For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love, Is God our Father dear; And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love, Is man, his child and care. For Mercy has a human heart Pity, a human face; And Love, the human form divine; And Peace, the human dress. Then every man, of every clime, That prays in his distress, Prays to the human form divine: Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace. And all must love the human form, In heathen, Turk, or Jew. Where Mercy, Love, and Pity dwell, There God is dwelling too. JH - C002 Commissioned for Amy & Ted on their wedding day, August 10, 2007. pdf download $1.75 Divine Image printed $3.25 treble choir, SSATB choir, oboe, & piano William Blake Jocelyn Hagen Andante = 92 q P Treble # # # # 3 ∑ ∑ ∑ ŒŒ Œ Choir & 4 œ œ œ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ œ œ œ œ ˙ T o Merœ --c y , Piœ t y , Peace,œ and Love,œ Oboe #### 3 & 4 ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ Œ ˙ molto p # ## # 3 . & 4 Œ œ j œ ˙. ˙ Œ œ j œ ˙. ˙. œ œ. œ œ œ. œ P ˙. ˙. ? # # 3 ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. # # 4 ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. ˙. pedal chordally 9 Tr. # # # # ∑ ŒŒ Œ & ∑ ∑ ˙ œ œ ˙ œ ˙. œ œ œ Allœ pray in their dis - tress, And 9 # Oboe ## # œ & ˙ œ œ œ ˙. œ œ ˙. -

Romantic Transformation : Visions of Difference in Blake and Wordsworth

ROMANTIC TRANSFORMATION: VISIONS OF DIFFERENCE IN BLAKE AND WORDSWORTH By RONALD BROGLIO A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Donald Ault for his visionary difference. Also thanks go out to my other committee members including John Leavey for his patience and kind advice, John Murchek for his insightful and exacting readings of my work, and Gayle Zachmann for her generosity in serving on my committee. For many, many hours in our collective construction of Romantic monstrosities, I thank my colleague and collaborator Bill Ruegg. For their friendship along the way, I thank Tom, Steph, and Trish. For all their support through my graduate career, I would like thank to my family. And I would like to thank Theresa for her loving companionship. For his inspirational indifference to my turmoils, I thank Bad Badtz-Maru. 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii LIST OF FIGURES v ABSTRACT vii CHAPTERS 1 THERMODYNAMIC TRANSFORMATION COUTNERING ORGANIC GROWTH 1 Metaphor and the First Law of Thermodynamies 4 The Gothic Church Meets the Second Law of Thermodynamics 16 Transformational Relations and Implications of Entropy 24 Notes 29 2 VECTORS OF READING AND TOPOGRAPHIES OF DEFIANCE IN WORDSWORTH'S LANDSCAPES 33 Reading for Time 34 The Simplon Pass: from the Sublime to the Transformational 37 The Penrith Beacon: The Collapse of an Architecture 53 Other Poems of -

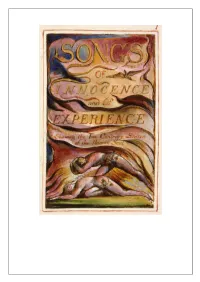

Songs of Innocence Is a Publication of the Pennsylvania State University

This publication of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence is a publication of the Pennsylvania State University. This Portable Document file is furnished free and without any charge of any kind. Any person using this document file, for any purpose, and in any way does so at his or her own risk. Neither the Pennsylvania State University nor Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, nor anyone associated with the Pennsylvania State University assumes any responsibility for the material contained within the document or for the file as an electronic transmission, in any way. William Blake’s Songs of Innocence, the Pennsylvania State University, Jim Manis, Faculty Editor, Hazleton, PA 18201-1291 is a Portable Document File produced as part of an ongoing student publication project to bring classical works of literature, in English, to free and easy access of those wishing to make use of them, and as such is a part of the Pennsylvania State University’s Elec- tronic Classics Series. Cover design: Jim Manis; Cover art: William Blake Copyright © 1998 The Pennsylvania State University Songs of Innocence by William Blake Songs of Innocence was the first of Blake’s illuminated books published in 1789. The poems and artwork were reproduced by copperplate engraving and colored with washes by hand. In 1794 he expanded the book to in- clude Songs of Experience. Frontispiece 3 Songs of Innocence by William Blake Table of Contents 5 …Introduction 17 …A Dream 6 …The Shepherd The images contained 19 …The Little Girl Lost 7 …Infant Joy in this publication are 20 …The Little Girl Found 7 …On Another’s Sorrow copies of William 22 …The Little Boy Lost 8 …The School Boy Blakes originals for 22 …The Little Boy Found 10 …Holy Thursday his first publication. -

G a L L E R Y B L a K E I N C O L O R

T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y B L A K E I N C O L O R facsimile plates from THE TRIANON PRESS presented by J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 205, San Francisco, CA 94108 williamblakegallery.com johnwindle.com T H E W I L L I A M B L A K E G A L L E R Y TERMS: All items are guaranteed as described and may be returned within 5 days of receipt only if packed, shipped, and insured as received. Payment in US dollars drawn on a US bank, including state and local taxes as ap- plicable, is expected upon receipt unless otherwise agreed. Institutions may receive deferred billing and duplicates will be considered for credit. References or advance payment may be requested of anyone ordering for the first time. Postage is extra and will be via UPS. PayPal, Visa, MasterCard, and American Express are gladly accepted. Please also note that under standard terms of business, title does not pass to the purchaser until the purchase price has been paid in full. ILAB dealers only may deduct their reciprocal discount, provided the account is paid in full within 30 days; thereafter the price is net. J O H N W I N D L E A N T I Q U A R I A N B O O K S E L L E R 49 Geary Street, Suite 233 San Francisco, CA 94108 T E L : (415) 986-5826 F A X : (415) 986-5827 C E L L : (415) 224-8256 www.johnwindle.com www.williamblakegallery.com John Windle: [email protected] Chris Loker: [email protected] Rachel Eley: [email protected] Annika Green: [email protected] Justin Hunter: [email protected] -

Songs of Innocence and of Experience by William Blake

SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE BY WILLIAM BLAKE 1789-1794 Songs Of Innocence And Of Experience By William Blake. This edition was created and published by Global Grey 2014. ©GlobalGrey 2014 Get more free eBooks at: www.globalgrey.co.uk No account needed, no registration, no payment 1 SONGS OF INNOCENCE INTRODUCTION Piping down the valleys wild Piping songs of pleasant glee On a cloud I saw a child. And he laughing said to me. Pipe a song about a Lamb: So I piped with merry chear, Piper pipe that song again— So I piped, he wept to hear. Drop thy pipe thy happy pipe Sing thy songs of happy chear, 2 So I sung the same again While he wept with joy to hear. Piper sit thee down and write In a book that all may read— So he vanish’d from my sight, And I pluck’d a hollow reed. And I made a rural pen, And I stain’d the water clear, And I wrote my happy songs, Every child may joy to hear 3 THE SHEPHERD How sweet is the Shepherds sweet lot, From the morn to the evening he strays: He shall follow his sheep all the day And his tongue shall be filled with praise. For he hears the lambs innocent call. And he hears the ewes tender reply. He is watchful while they are in peace, For they know when their Shepherd is nigh. 4 THE ECCHOING GREEN The Sun does arise, And make happy the skies. The merry bells ring, To welcome the Spring. -

William Blake ( 1757-1827)

William Blake ( 1757-1827) "And I made a rural pen, " "0 Earth. 0 Earth, returnl And I stained the water clear, "Arise from out the dewy grass. And J wrote my happy songs "Night is worn. Every child may joy to hear." "And the mom ("Introduction". Songs of Innocence) "Rises from the slumberous mass." ("Introduction''. Songs of Experience! 19 Chapter- 2 WILLIAM BLAKE "And I made a rural pen, And I stain'd the water clear, And I wrote my happy songs Every child may joy to hear. "1 "Then come home, my children, the sun is gone down, And the dews of night arise; Your spring and your day are wasted in play, · And your winter and night in disguise. "1 Recent researches have shown the special importance and significance of childhood in romantic poetry. Blake, being a harbinger of romanticism, had engraved childhood as a state of unalloyed joy in his Songs of Innocence. And among the romantics, be was perhaps the first to have discovered childhood. His inspiration was of course the Bible where he had seen the image of the innocent, its joy and all pure image of little, gentle Jesus. That image ignited the very ·imagination of Blake, the painter and engraver. And with his illuntined mind, he translated that image once more in his poetry, Songs of Innocence. Among the records of an early meeting of the Blake Society on 12th August, 1912 there occurs the following passage : 20 "A pleasing incident of the occasion was the presence of a very pretty robin, which hopped about unconcernedly on the terrace in front of the house and among the members while the papers were being read..