This May Be the Author's Version of a Work That Was Submitted/Accepted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017

Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 Annual Report 2017 1 Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 Vision Statement: Cork City Council is a dynamic, responsive and inclusive organisation leading a prosperous and sustainable city. 2 Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 CONTENTS: Foreword by Lord Mayor & Chief Executive Members of Cork City Council Senior Management Team Meetings/Committees/Conferences City Architect’s Department Corporate and External Affairs Environment and Recreation Housing and Community ICT and Business Services Human Resource Management & Organisation Reform Strategic Planning and Economic Development Roads and Transportation Financial Statements Recruitment Information Review of the 2017 Annual Service Delivery Plan 3 Comhairle Cathrach Chorcaí Tuarascáil Bhliantúil 2017 Lord Mayor’s & Chief Executive’s Foreword In the words of Cork poet Thomas McCarthy, “a city rising is a beautiful thing”. Cork City is a City Rising. Retail units are opening for business in the €50m Capitol retail and office complex. Work has started on the €90 million Navigation House office development on Albert Quay and over the summer, Cork City Council agreed the sale of 7-9 Parnell Place and 1-2 Deane Street to Tetrarch Capital who propose to build a budget boutique hotel and designer hostel with ground floor restaurants and bars. Earlier this year, Boole House was handed over to UCC and also over the summer, the Presentation Sisters opened Nano Nagle Place on Douglas Street. This is all progress. Our strategy at Cork City Council has been to deliver for the Cork region through a revitalised, vibrant city centre – to our mind, the city centre is the ‘healthy heart’ of Cork. -

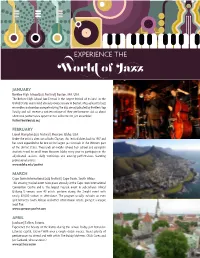

World of Jazz

EXPERIENCE THE World of Jazz JANUARY Berklee High School Jazz Festival | Boston, MA, USA The Berklee High School Jazz Festival is the largest festival of its kind in the United States and is held annually every January in Boston, Massachusetts! Jazz ensembles and combos compete during the day, are adjudicated by Berklee’s top faculty and will receive a written critique of their performance. Ask us about additional performance opportunities in Boston for jazz ensembles! festival.berkleejazz.org FEBRUARY Lionel Hampton Jazz Festival | Moscow, Idaho, USA Under the artistic direction of John Clayton, this festival dates back to 1967 and has since expanded to be one of the largest jazz festivals in the Western part of the United States. Thousands of middle school, high school and collegiate students travel to small town Moscow, Idaho every year to participate in the adjudicated sessions, daily workshops and evening performances featuring professional artists! www.uidaho.edu/jazzfest MARCH Cape Town International Jazz Festival | Cape Town, South Africa This amazing musical event takes place annually at the Cape Town International Convention Centre and is the largest musical event in sub-Saharan Africa! Utilizing 5 venues, over 40 artists perform during the 2-night event with nearly 40,000 visitors in attendance. The program usually includes an even split between South African and other international artists, giving it a unique local flair. www.capetownjazzfest.com APRIL Jazzkaar | Tallinn, Estonia Experience the beauty of the Baltics during this annual 10-day jazz festival in Estonia’s capital, Tallinn! With over a couple dozen venues, there’s plenty of performances to attend and with artists like Bobby McFerrin, Chick Corea and Jan Garbarek, who can resist? www.jazzkaar.ee/en MAY Brussels Jazz Marathon | Brussels, Belgium Belgium’s history of jazz really begins with Mr. -

Mike Mcgrath-Bryan M.A

MIKE MCGRATH-BRYAN M.A. Journalism with New Media, CIT Selected Features Journalism & Content Work 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS: GENDER REBELS: FIGHTING FOR RIGHTS AND VISIBILITY (Evening Echo, August 31st 2018) 3 MOVEMBER: “IT’S AN AWFUL SHOCK TO THE SYSTEM” (Evening Echo, November 13th 2017) 7 REBEL READS: TURNING THE PAGE (Totally Cork, September 2018) 10 FRANCISCAN WELL: FEM-ALE PRESSURE (Evening Echo, July 26th 2018) 12 CORK VINTAGE MAP: OF A CERTAIN VINTAGE (Totally Cork, December 6th 2016) 14 THE RUBBERBANDITS: HORSE SENSE (Evening Echo, December 12, 2016) 16 LANKUM: ON THE CUSP OF THE UNKNOWN (Village Magazine, November 2017) 19 CAOIMHÍN O’RAGHALLAIGH: “IT’S ABOUT FINDING THE RIGHT SPACE” (RTÉ Culture, September 6th 2018) 25 THE JAZZ AT 40: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE (Evening Echo: Jazz Festival Special, October 17th 2017) 28 CORK MIDSUMMER FESTIVAL: THE COLLABORATIVE MODEL (Totally Cork, May 2018) 31 DRUID THEATRE: “VERY AWARE OF ITSELF” (Evening Echo, February 12th 2018) 33 CORK CITY BALLET: EN POINTE (Evening Echo, September 3rd, 2018) 35 2 GENDER REBELS: FIGHTING FOR RIGHTS AND VISIBILITY (Evening Echo, August 31st 2018) Gender Rebels are a group dedicated to working on the rights of transgender, intersex and non-binary people in Cork City, negotiating obstacles both infrastructural and everyday, and providing an outlet for social events and peer support. Mike McGrath-Bryan speaks with chairperson Jack Fitzgerald. With Pride month in the rear view mirror for another year, and celebrations around the country winding down, it’s easy to bask in the colour, pomp and circumstance that the weekend’s proceedings confer on the city. -

4 Cork Business of the Year Awards: 6 Lower Lee Flood

Autumn 2019 / Q4 C ed C www.corkbusiness.ie CORK’S BETTER BUILDING AWARDS: 4 CORK BUSINESS OF THE YEAR AWARDS: 6 LOWER LEE FLOOD RELIEF: 8 ROCHESTOWN PARK HOTEL COOKBOOK: 10 NEW MEMBERS: 12 INFRASTRUCTURE: 14 TOURISM, FESTIVALS & EVENTS: 17 RETAIL: 24 SOCIAL: 25 SPONSORED BY Welcome to the Cork Business Association’s OUR STRENGTH IS IN OUR NUMBERS. Welcome to quarterly magazine Cork Connected. We are the We focus on the following areas: Retail, Hospitality, voice of businesses in Cork, and we are dedicated to Tourism, City Infrastructure, Public Realm Issues, Cork Business promoting their interests at local and national level, Rates, Rents, Parking, Anti-social Behaviour, Crime, and Cork City as the premier commercial and tourist Street Cleaning, Casual Trading, Litter Control, Association’s destination in the Southern region of Ireland. Business Advice, Flood and Weather Alerts, Graffiti Removal, Business Awards, Marketing of Cork, newsletter The Cork Business Association ensures that you Networking and Social Events. have a stronger voice when dealing with local and national issues that affect your business. ello to everyone and I hope you had a great in the city as opposed to shopping online. I would ask summer and are ready now for the next business every one of us to encourage our employees and families President’s Hcycle in Cork. to shop local and put the money back into the local I attended the Guinness Cork Jazz festival launch economy. address recently, this is always a big weekend in the life of Cork We cannot be but impressed with the pace of City both socially and from a business sense. -

National Festivals and Events Calendar 2019

National Festivals and Events Calendar 2019 Some countries have seasons dedicated to festivals but here in Ireland we have an entire calendar of events for your visitor to immerse themselves in. There’s something for everyone, from traditional Irish music to opera, poetry to music festivals, country escapes to city takeovers. We have hundreds of festivals and events to choose from, guaranteeing your visitor a trip to remember!! 1 ST PATRICK’S FESTIVAL DUBLIN 14-18 March 2019 St. Patrick’s Festival is a national cultural event where Ireland welcomes the world to Dublin for a celebration of contemporary Irish culture and our rich Irish heritage. The theme for 2019 is storytelling/scéalaíocht – Ireland has a deep-rooted connection with storytelling reaching back thousands of years and spanning the centuries up to the storytellers of today. Through music, visual art, literature, film, theatre, spoken word, street theatre and circus, St Patrick’s Festival Dublin will celebrate Ireland’s rich heritage of storytelling. The parade on the 17th March is a prestigious performance platform where some of the world’s top marching bands travel to participate annually. Around 3,000 participants will perform. Pageant companies from all over Ireland are commissioned to produce bespoke parade pageants in line with the Festival theme. www.stpatricksfestival.ie 2 IRELAND’S ST. PATRICK’S DAY CELEBRATIONS March 2019 St. Patrick’s Day on the 17th March is one of the biggest day’s in Ireland’s cultural calendar. It is also a national holiday with the very best of Irish and international talent on show at countless festivals and events across the country to celebrate St. -

Annes Grove Gatelodge

Annes grove Gatelodge Sleeps 2 - Castletownroche, Co Cork Situation: Presentation: A miniature medieval castle, Annes Grove Gatelodge was designed in 1853 to impress visitors to the main house - Annesgrove House and Gardens. The silence which surrounds this rural property is part of the charm for our visitors. Beyond the gate, in the privacy of a small garden, guests can enjoy great peace and tranquility - and the small patio offers a wonderful opportunity to dine 'al fresco' on balmy summer evenings. Inside timber ceilings, wood floors, stone arches, and snug rooms make this property an idyllic setting for those looking for a romantic break. La maison de Gardien d’Annes Grove est un château médiéval miniature construit en 1853 pour impressionner les visiteurs de la maison principale: ‘Annes grove House and Gardens’. Le silence qui entoure cette propriété rurale fait partie du charme de ce lieu. Au-delà de la porte, dans l'intimité d'un petit jardin, vous pourrez goûter au grand calme et à la tranquillité. Le petit patio offre une merveilleuse occasion de dîner à l’extérieur lors des douces soirées d'été. Il s'agit d'un bâtiment intensément romantique. A l'intérieur, des poutres, planchers de bois, arches en pierre et chambres douillettes donne à cette propriété un cadre idyllique pour ceux qui recherchent une escapade romantique. History: Annes Grove is built in Gothic style. It is situated at the junction of three quiet country roads and surrounded by mature beech trees, which cradle the property and stonewalls. Annes Grove was designed by Benjamin Woodward, of the distinguished firm of architects Deane and Woodward in 1853. -

The Gathering Ireland 2013 Has Been Described As “The Largest Ever Tourism Initiative” in Ireland

P a g e | 0 FINAL REPORT December 2013 The Gathering Final Report | 1 Contents FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 3 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 8 2. PROJECT ORGANISATION & STRUCTURE ...................................................................................... 11 3. CITIZEN AND COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT ................................................................................... 15 4. PARTNERS & STRATEGIC ALLIANCES ............................................................................................. 23 5. EVENTS FUNDING & SUPPORT ...................................................................................................... 29 6. MARKETING & COMMUNICATIONS .............................................................................................. 35 7. PROJECT PERFORMANCE AND IMPACT ........................................................................................ 47 APPENDICES….......................................................................................................................................53 The Gathering Final Report | 2 FOREWORD The Gathering Ireland 2013 has been described as “the largest ever tourism initiative” -

Parttime-Csm-Prospectus-2016.Pdf

Information for Students and Staff 2016-17 Cover image is a photo from the BA (Theatre & Drama Studies) April 2016 production of Animal Farm, directed by Donal Gallagher Information for Students & Staff 2016-17 Contents Introduction 1 Brief History of CSM 2 Artists-in-Residence 3 CSM Calendar 7 Concerts Calendar 9 CSM Awards 2015-16 11 CSM Performing Groups 15 Enrolment Information 16 Payment of Fees 18 Part-time Courses: Information 19 Health & Safety Matters 25 CSM Competitions 2016-17 27 Staff Lists & Contact Details 34 rRRR Introduction Welcome to the 2016-17 CSM Academic Year! I hope you are looking forward to a rewarding and fulfilling year as a student, parent or staff member and that you will avail of many of the opportunities open to you as a member of the CIT Cork School of Music community. We at the CSM pride ourselves on the holistic nature of our music and drama education, spanning four levels of education, which places us amongst leading conservatoires nationally and internationally. Geoffrey Spratt, Director of Cork School of Music, retires in August 2016. Having been in the post since 1992, Geoff has overseen the development of 3rd and 4th level degree pro- grammes in music and drama and the School is very proud of its graduates of the BMus, MA in Music, MA & MSc in Music Technology, and its first crop of graduates in 2016 of the BA in Popular Music, and the BA in Theatre and Drama Studies; a new milestone indeed! Amongst the many noteworthy landmarks of Geoff’s term as Director is, of course, the real- isation in 2007 of the magnificent state-of-the-art building that is now the CIT Cork School of Music on Union Quay, truly a landmark in every sense of the word. -

Jazz Appreciation Month

A Report on the Ninth Annual Jazz Appreciation Month April 2010 Jazz Appreciation Month Mission and Vision Jazz Appreciation Month provides leadership to advance the field of jazz and promote it as a cultural treasure born in America and celebrated worldwide. Vision Statement -The Smithsonian‘s National Museum of American History will work collaboratively with JAM Partners and Supporters worldwide to fulfill JAM‘s mission by: -Making jazz fun and accessible for all. -Highlighting the music‘s rich legacy and vibrant place in contemporary life and cultural diplomacy. -Making jazz relevant and cool for today‘s youth. -Using the Smithsonian‘s vast jazz collections, exhibits and research resources to develop education/ performance events that teach the public about the roots of jazz, its masters and the music. -Preserving the heritage of jazz and entertaining the public with classical and rarely heard jazz music performed by the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra and others. -Building the music‘s future by inspiring, training and highlighting the next generation of jazz performers, edu- cators, and appreciators. -Making jazz synonymous with ideals of freedom, creativity, innovation, democracy, cultural diversity, and au- thenticity. Table of Contents Notes from the American Music Curator……………………………………………………………….1 Notes from the JAM Program Director………………………………………………………………....2 Notes from the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Executive Producer…………………………………...3 JAM Task Force and Committees……………………………………………………………………....4 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………….5 -

MINUTES of ORDINARY MEETING of CORK CITY COUNCIL HELD on MONDAY 11Th JANUARY 2021

MINUTES OF ORDINARY MEETING OF CORK CITY COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY 11th JANUARY 2021 PRESENT Ardmhéara Comhairleoir J. Kavanagh. NORTH EAST Comhairleoirí K. O’Flynn, J. Maher, T. Tynan, O. Moran, G. Keohane. NORTH WEST Comhairleoirí T. Fitzgerald, M. Nugent, J. Sheehan, K. Collins, D. Boylan. SOUTH EAST Comhairleoirí D. Cahill, L. Bogue, M.R. Desmond, K. McCarthy, T. Shannon, D. Forde. SOUTH CENTRAL Comhairleoirí M. Finn, D. Boyle, S. Martin, S. O’Callaghan, P. Dineen, F. Kerins. SOUTH WEST Comhairleoirí F. Dennehy, D. Canty, C. Finn, C. Kelleher, G. Kelleher, T. Moloney, H. Cremin. ALSO PRESENT Ms. A. Doherty, Chief Executive. Mr. B. Geaney, Assistant Chief Executive. Mr. P. Moynihan, Director of Services, Corporate Affairs & International Relations. Mr. G. O’Beirne, Director of Services, Infrastructure Development. Mr. F. Reidy, Director of Services, Strategic & Economic Development. Mr. D. Joyce, Director of Services, Roads & Environment Operations. Ms. A. Rodgers, Director of Services, Community, Culture & Placemaking. Mr. J. Hallahan, Chief Financial Officer. Mr. T. Duggan, City Architect. Mr. T. Keating, Interim Director of Services, Housing. Mr. A. Mahony, Senior Executive Engineer, Roads & Environment Operations. Ms. A. Murnane, Meetings Administrator. Ms. C. Currid, A/Administrative Officer, Corporate Affairs & International Relations. An tArdmhéara recited the opening prayer. 1. LORD MAYOR’S ITEMS 1.1 ATTENDANCE OF ELECTED MEMBERS AT COUNCIL BUILDINGS In light of the deteriorating situation regarding Covid19, An tArdmhéara reminded An Chomhairle of the AILG/LGMA/LAMA Standard Operating Guidance regarding attendance of Elected Members at Council buildings. He advised that attendance should be by pre-arranged appointment, and for essential business reasons only. -

1 Minutes of Ordinary Meeting of Cork City Council Held

MINUTES OF ORDINARY MEETING OF CORK CITY COUNCIL HELD ON MONDAY 11th JANUARY 2016 PRESENT An tArd-Mhéara Comhairleoir C. O’Leary. NORTH EAST Comhairleoirí S. Cunningham, T. Tynan, T. Brosnan, J. Kavanagh. NORTH CENTRAL Comhairleoirí, T. Gould, M. Barry, L. O’Donnell J. Sheehan. NORTH WEST Comhairleoirí M. Nugent, T. Fitzgerald, K. Collins, M. O’Sullivan. SOUTH EAST Comhairleoirí K. McCarthy, L. McGonigle, N. O’Keeffe, S. O’Shea. SOUTH CENTRAL Comhairleoirí M. Finn, F. Kerins, T. O’Driscoll, S. Martin. SOUTH WEST Comhairleoirí J. Buttimer, H. Cremin, M. Shields, F. Dennehy, P.J. Hourican, T. Moloney. ALSO PRESENT Ms. A. Doherty, Chief Executive Officer Mr. J.G. O’Riordan, Meetings Administrator, Corporate & External Affairs. Ms. J. Gazely, Senior Staff Officer, Corporate & External Affairs. Ms. U. Ramsell, Staff Officer, Corporate & External Affairs. Mr. P. Moynihan, Director of Services, Corporate & External Affairs. Ms. V. O’Sullivan, Director of Services, Housing & Community. Mr. G. O’Beirne, Director of Services, Roads & Transportation. Mr. J. O’Donovan, Director of Services, Environment & Recreation. Mr. P. Ledwidge, Director of Services, Strategic Planning and Economic Development. Mr. J. Hallahan, A/ Head of Finance. Mr. T. Duggan, City Architect. An tArd-Mhéara recited the opening prayer. 1. VOTES OF SYMPATHY • The O’Brien Family on the death of Alan O’Brien • The Twomey Family on the death of Ann Twomey • The Mannix Family on the death of David Mannix • The Dermody Family on the death of Irene Dermody • The Mulcahy Family on the death of Donal Mulcahy • The Philpott Family on the death of Eric Philpott • The Clarke Family on the death of John Clarke 2. -

Architecture Exhibitions Events Education Contents

Your FREE guide to what’s on in the museum until November 2018 Architecture Exhibitions Events Education Contents Architecture + Exhibitions The Glucksman building.................................................2 Josef and Anni Albers.................................................3 Please Touch.................................................4 PeopLe and the PLanet.................................................5 Art in the Foyer.................................................6 UCC Art Collection.................................................7 Events VIBE events.................................................8 Perspectives.................................................9 2018 Residents.................................................10 Heritage Week...............................................11 Culture Night...............................................12 Inclusive Arts...............................................13 Family Sundays...............................................14 Music...............................................15 Craft + Design Fair...............................................16 Education Tours...............................................18 Creative Tech Club...............................................19 Schools Workshops...............................................20 Teacher Programmes...............................................21 Adult Art Courses...............................................22 Art Club Senior...............................................23 Information Museum shop and