How Smoking Affects the Way You Look

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Effects of Mouthwash on the Human Oral Mucosae: with Special References to Sites, Sex Differences and Smoking

J. Nihon Univ. Sch. Dent., Vol. 39, No. 4, 202-210, 1997 A study of effects of mouthwash on the human oral mucosae: With special references to sites, sex differences and smoking Kayo Kuyama1 and Hirotsugu Yamamoto2 Departments of Public Health1 and Pathology2, Nihon University School of Dentistry at Matsudo (Received8 Septemberand accepted20 September1997) Abstract : In recent years, the use of mouthwash an ingredientof almost all mouthwashesat zero to 23.0 % has become widespread as a part of routine oral (9, 10), was discussed in particular (4, 6-8). In this hygiene. However, there have been no fundamental connection,Gagari et al. (1) pointed out that the exposure studies on the influence of mouthwashes on the human time of ethanol to the oral mucosae by mouthwashing oral mucosae. One hundred and twenty-five subjects was probably longer than that provided by drinking an (50 males and 75 females) were selected for this study. alcoholic beverage. The inflammation and/or The effects of mouthwash was assessed with the use of hyperkeratosis of the hamster cheek pouch caused by exfoliative cytological and cytomorphometric analyses exposure to a commerciallyavailable mouthwash with a of smears obtained from clinically normal upper high ethanol content were examined (11, 12). In a study labium and cheek mucosae before mouthwashing, 30 of human oral mucosae, epithelial peeling, ulceration, s, 10 min and 1 h after mouthwashing. The inflammationand other miscellaneouschanges occurred independent variables examined were oral site, sex in the mucosae as a result of mouthwashing with high- and smoking (smokers versus never-smokers). In all alcoholproducts (13). -

Tax, Price and Cigarette Smoking

i62 Tob Control: first published as 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i62 on 1 March 2002. Downloaded from Tax, price and cigarette smoking: evidence from the tobacco documents and implications for tobacco company marketing strategies F J Chaloupka, K M Cummings, CP Morley, JK Horan ............................................................................................................................. Tobacco Control 2002;11(Suppl I):i62–i72 Objective: To examine tobacco company documents to determine what the companies knew about the impact of cigarette prices on smoking among youth, young adults, and adults, and to evaluate how this understanding affected their pricing and price related marketing strategies. Methods: Data for this study come from tobacco industry documents contained in the Youth and Marketing database created by the Roswell Park Cancer Institute and available through http:// roswell.tobaccodocuments.org, supplemented with documents obtained from http://www. See end of article for tobaccodocuments.org. authors’ affiliations Results: Tobacco company documents provide clear evidence on the impact of cigarette prices on ....................... cigarette smoking, describing how tax related and other price increases lead to significant reductions in smoking, particularly among young persons. This information was very important in developing the Correspondence to: F J Chaloupka, Department industry’s pricing strategies, including the development of lower price branded generics and the pass of Economics (m/c 144), through of cigarette excise tax increases, and in developing a variety of price related marketing efforts, University of Illinois at including multi-pack discounts, couponing, and others. Chicago, 601 South Conclusions: Pricing and price related promotions are among the most important marketing tools Morgan Street, Chicago, IL 60607-7121, USA; employed by tobacco companies. -

Oral Health and Smoking Information for You

Oral health and smoking Information for you Follow us on Twitter @NHSaaa FindVisit our us website: on Facebook www.nhsaaa.net/better-health at www.facebook.com/nhsaaa FollowVisit our us on website: Social Media www.nhsaaa.net @AyrshireandArranOHI @NHSOHI All our publications are available in other formats Steps for good oral health: • Keep sugary snacks and drinks to mealtimes • Brush teeth twice a day using 1450ppm fluoride toothpaste • Visit the dentist regularly 2 How can smoking affect my oral health? Most people are now aware that smoking is bad for their health. It can cause many different medical problems and in some cases fatal diseases. However, many people don’t realise the damage that smoking does to their mouth, gums and teeth. Smoking can lead to tooth staining, gum disease, tooth loss, bad breath (halitosis), reduced sense of taste and smell, reduced blood supply to the mouth and in more severe cases mouth cancer. Can smoking lead to gum disease? Patients who smoke are more likely to produce bacterial plaque, which leads to gum disease. The gums are affected because smoking causes a lack of oxygen in the bloodstream, so the infected gums fail to heal. Smoking can lead to an increase in dental plaque and cause gum disease to progress more quickly than in non-smokers. 3 Smoking can mask problems with your gums, and often when you stop smoking your gums will begin to bleed. For more information see the ‘Gum disease, sensitivity and erosion’ leaflet. Gum disease still remains the most common cause of tooth loss in adults. -

How Much Does Smoking Cost? It Is Important for You to Realize How Much Money You Spend on Tobacco

SECTION 5: Group 1 – Handouts 2012 Chapter 6 How Much Does Smoking Cost? It is important for you to realize how much money you spend on tobacco. Smoking cigarettes is very expensive. It costs $7.00 or more to buy a pack of cigarettes today. The tobacco companies only spend only pennies (about 6 cents) to make a pack of cigarettes. That means that the tobacco companies make several dollars profit on each pack of cigarettes that you buy and the government gets a few dollars! The more you smoke…the more money the tobacco industry makes. Did you know that the Tobacco Companies make more than $32 billion dollars each year Important point to remember: 1 Pack of Cigarettes Costs Approx $7.00 Minus 6 Cents it Costs to Make -.06 BALANCE $6.94 This balance includes the profits made by the tobacco companies and taxes paid to the government. Learning about Healthy Living – Revised 2012 Page | 58 SECTION 5: Group 1 – Handouts 2012 Chapter 6 How much does smoking cost? Look at the chart below and estimate how much smoking cigarettes costs you every day, week, month and year. Sometimes we don’t realize how much we are spending on things until we stop to total the cost. The following chart is based on a pack of cigarettes costing about $7.00: Column 1 2 3 4 5 6 Approximate Number Average Average Average Average Average Cost of Cigarettes that I Cost Per Cost Per Cost Per Cost Per in 10 Years Smoke Each Day Day Week Month Year ½ pack (10 cigs) $3.50 $24.50 $98.00 $1,176.00 $11,760.00 1 pack (20 cigs) $7.00 $49.00 $196.00 $2,352.00 $23,520.00 1 -

Pretreatment Oral Hygiene Habits and Survival of Head and Neck

Friemel et al. BMC Oral Health (2016) 16:33 DOI 10.1186/s12903-016-0185-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Pretreatment oral hygiene habits and survival of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients Juliane Friemel1†, Ronja Foraita1†, Kathrin Günther1, Mathias Heibeck1, Frauke Günther1, Maren Pflueger1, Hermann Pohlabeln1, Thomas Behrens2, Jörn Bullerdiek3, Rolf Nimzyk3 and Wolfgang Ahrens1* Abstract Background: The survival time of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is related to health behavior, such as tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption. Poor oral health (OH), dental care (DC) and the frequent use of mouthwash have been shown to represent independent risk factors for head and neck cancerogenesis, but their impact on the survival of HNSCC patients has not been systematically investigated. Methods: Two hundred seventy-six incident HNSCC cases recruited for the ARCAGE study were followed through a period of 6–10 years. Interview-based information on wearing of dentures, gum bleeding, teeth brushing, use of floss and dentist visits were grouped into weighted composite scores, i.e. oral health (OH) and dental care (DH). Use of mouthwash was assessed as frequency per day. Also obtained were other types of health behavior, such as smoking, alcohol drinking and diet, appreciated as both confounding and study variables. Endpoints were progression-free survival, overall survival and tumor-specific survival. Prognostic values were estimated using Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression models. Results: A good dental care score, summarizing annual dental visits, daily teeth cleaning and use of floss was associated with longer overall survival time (p = .001). -

Do You Know... Tobacco

Do You Know... What is it? Tobacco is a plant (Nicotiana tabacum and Tobacco Nicotiana rustica) that contains nicotine, an addictive drug with both stimulant and depressant effects. Tobacco is most commonly smoked in cigarettes. It is also smoked in cigars or pipes, chewed as chewing tobacco, sniffed as dry snuff or held inside the lip or cheek as wet snuff. Tobacco may also be mixed with cannabis and smoked in “joints.” All methods of using tobacco deliver nicotine to the body. Although tobacco is legal, federal, provincial and municipal laws tightly control tobacco manufacture, marketing, distribution and use. Second-hand tobacco smoke is now recognized as a health danger, which has led to increasing restrictions on where people can smoke. Violations of tobacco-related laws can result in fines and/or prison terms. 1/5 © 2003, 2010 CAMH | www.camh.ca Where does tobacco come from? How does tobacco make you feel? The tobacco plant’s large leaves are cured, fermented The nicotine in tobacco smoke travels quickly to the and aged before they are manufactured into tobacco brain, where it acts as a stimulant and increases heart products. Tobacco was cultivated and widely used by rate and breathing. Tobacco smoke also reduces the the peoples of the Americas long before the arrival of level of oxygen in the bloodstream, causing a drop in Europeans. Today, most of the tobacco legally produced skin temperature. People new to smoking are likely to in Canada is grown in Ontario, commercially packaged experience dizziness, nausea and coughing or gagging. and sold to retailers by one of three tobacco companies. -

Quitting Smoking Is the Most Important Step You Can Take to Improve Your Health

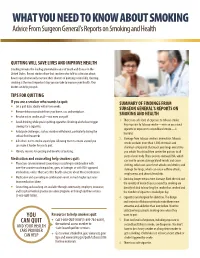

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT SMOKING Advice From Surgeon General’s Reports on Smoking and Health QUITTING WILL SAVE LIVES AND IMPROVE HEALTH Smoking remains the leading preventable cause of death and disease in the United States. Recent studies show that smokers who talk to a clinician about how to quit dramatically increase their chances of quitting successfully. Quitting smoking is the most important step you can take to improve your health. Your doctor can help you quit. TIPS FOR QUITTING If you are a smoker who wants to quit: SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FROM l Set a quit date, ideally within two weeks. l SURGEON GENERAL’S REPORTS ON Remove tobacco products from your home, car, and workplace. SMOKING AND HEALTH l Resolve not to smoke at all—not even one puff. 1. There is no safe level of exposure to tobacco smoke. l Avoid drinking while you’re quitting cigarettes. Drinking alcohol can trigger cravings for a cigarette. Any exposure to tobacco smoke—even an occasional cigarette or exposure to secondhand smoke—is l Anticipate challenges, such as nicotine withdrawal, particularly during the harmful. critical first few weeks. 2. Damage from tobacco smoke is immediate. Tobacco l Ask others not to smoke around you. Allowing them to smoke around you smoke contains more than 7,000 chemicals and can make it harder for you to quit. chemical compounds that reach your lungs every time l Identify reasons for quitting and benefits of quitting. you inhale. Your blood then carries the poisons to all parts of your body. These poisons damage DNA, which Medication and counseling help smokers quit: can lead to cancer; damage blood vessels and cause l Physicians can recommend counseling or coaching in combination with clotting, which can cause heart attacks and strokes; and over-the-counter nicotine patches, gum, or lozenges or with FDA-approved damage the lungs, which can cause asthma attacks, medications, unless there are other health concerns about those medications. -

Healthypeople Dental

JUNE | 2017 HealthyPeople ●Dental CELEBRATE NATIONAL SMILE MONTH Good oral health can have so many wonderful life-changing benefits. From greater self- confidence to better luck in careers and relationships, a healthy smile can truly transform your visual appearance, the positivity of your mind-set, as well as improving the health of not only your mouth but your body too. As part of National Smile Month, here are some top tips covering all areas of your oral health, to help keep you smiling. CARING FOR YOUR MOUTH Brush your teeth last thing at night and at least one other time during the day with a fluoride toothpaste. Clean between your teeth at least once a day using interdental brushes or floss. If you use mouthwash don’t use it directly after brushing as you rinse away the fluoride from your toothpaste. Quit smoking to help reduce the chances of tooth staining, gum disease, tooth loss, and in more severe cases mouth cancer. Make sure your toothpaste contains fluoride; it helps strengthen tooth enamel making it more resistant to decay. Change your toothbrush every two to three months or sooner if it becomes worn as it will not clean the teeth properly. REGULAR DENTAL CARE IS ESSENTIAL VISITING THE DENTIST Avoid snacking and try to only have sugary foods and drinks at mealtimes, reducing the Visit your dentist regularly, as often as time your teeth come under attack. recommended. DIET AND YOUR ORAL HEALTH If you have a sweet tooth, try to choose Some dentists may offer home visits Chew sugar-free gum after eating or sugar-free sweets and drinks which contain for those housebound or have other drinking to help protect your teeth and xylitol as it can actively contribute to your difficulties visiting the office. -

Cigarette Type Or Smoking History

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Cigarette type or smoking history: Which has a greater impact on the metabolic syndrome and its components? Sarah Soyeon Oh1,2, Ji‑Eun Jang1,4, Doo‑Woong Lee1,2, Eun‑Cheol Park1,3 & Sung‑In Jang1,3* Few studies have researched the gender‑specifc efects of electronic nicotine delivery systems on the metabolic syndrome (MetS) and/or its risk factors (central obesity, raised triglycerides, decreased HDL cholesterol, raised blood pressure, raised fasting plasma glucose). Thus, this study investigated the association between smoking behavior (cigarette type, smoking history) and MetS in a nationally representative sample of Korean men and women. Our study employed data for 5,462 cases of MetS and 12,194 controls from the Korea National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (KNHANES) for the years 2014 to 2017. Logistic regression analysis was employed to determine the association between type of cigarette (non‑smoker, ex‑smoker, and current smoker—conventional only, current smoker—conventional and electronic) and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its risk factors. Smoking history was clinically quantifed by pack‑year. No association between cigarette type and MetS was found for men. For women, relative to non‑smokers, smokers of conventional cigarettes (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.02–3.18) and both conventional and electronic cigarettes (OR 4.02, 95% CI 1.48–10.93) had increased odds of MetS. While there was no association between smoking history and MetS for women, for men, conventional smoking history was associated with MetS for individuals with a smoking history of > 25 pack‑years (> 25 to ≤ 37.5 OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.04–2.02; > 37.5 to ≤ 50 OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.08–2.18; > 50 OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.07–2.27). -

Smoking Before High School

THE PATH TO TOBACCO ADDICTION STARTS AT VERY YOUNG AGES Lifetime smoking and other tobacco use almost always begins by the time kids graduate from high school.1 Young kids’ naïve experimentation frequently develops into regular smoking, which typically turns into a strong addiction—well before the age of 18—that can overpower the most well-intentioned efforts to quit. Any efforts to decrease future tobacco use levels among high school students, college-aged youths or adults must include a focus on reducing experimentation and regular tobacco use among teenagers and pre-teens. How Early Do Kids Try Smoking? Every day about 1,600 kids under 18 try smoking for the first time.2 Though very little data about smoking is regularly collected for kids under 12, the peak years for first trying to smoke appear to be in the sixth and seventh grades (or between the ages of 11 and 13), with a considerable number starting even earlier.3 A 2019 nationwide survey found that 7.9 percent of high school students had tried cigarette smoking (even one or two puffs) before the age of 13.4 The 2020 nationwide Monitoring the Future Study reports that 24.0 percent of twelfth grade students,13.9 percent of tenth grade students, and 11.5 percent of eighth grade students had ever tried smoking.5 According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, nearly 80 percent of all adult smokers begin smoking by age 18; and 90 percent do so before leaving their teens.6 One study found that in 2018, 51.3% of lifetime cigarette users had initiated use at 14 years or younger -

Factsheet: Passive Smoking

Passive smoking What is passive smoking? infant death syndrome. Also it has harmful effects on the developing lung and immune system resulting in Passive smoking is breathing in smoke from other decreased lung function at birth and increased allergic people’s cigarettes, cigars or pipes. Smoke that is and asthmatic response in childhood. breathed out by a smoker is called mainstream smoke. The smoke drifting from the burning end of a cigarette is called sidestream smoke. Second Hand Smoke (SHS) also known as Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) is a What is the health risk for children? combination of mainstream and sidestream smoke with Children exposed to SHS are at risk of sudden infant each contributing to about half of the smoke generated. death syndrome and are more likely to develop a Smoking parents are the most common source of ETS range of illnesses including asthma, croup, exposure for children. bronchitis, bronchiolitis, pneumonia and middle ear Sidestream smoke stays in a room longer and contains infections, compared to children living in smoke-free many cancer causing substances, more than mainstream environments. smoke. As we spend more and more time indoors, SHS is Impaired learning, slower growth and changes in a serious but preventable health hazard. Children in behavior have been linked with children’s exposure particular are at risk of harmful effects from passive to passive smoke. smoking. Both asthma and respiratory infections What is the health risk for unborn babies? (characterised by wheezing, breathlessness, cough Smoking during pregnancy is harmful to the developing and phlegm) are increased in children who are baby. -

Secondhand Smoke March 2020

Secondhand Smoke March 2020 Introduction Breathing in other people’s cigarette smoke is called passive, involuntary or secondhand smoking (SHS). Secondhand smoke, also called “environmental tobacco smoke”, comprises “sidestream” smoke from the burning tip of the cigarette and “mainstream” smoke which is smoke that has been inhaled and then exhaled by the smoker. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) classifies environmental tobacco smoke as a Class A (known human) carcinogen alongside asbestos, arsenic, benzene and radon gas.1 There is no safe level of exposure to SHS.2 Worldwide, an estimated 33% of male non-smokers, 35% of female non-smokers and 40% of children are exposed to SHS.3 What’s in secondhand smoke? Tobacco smoke contains over 4000 chemicals in the form of particles and gases.1 Many potentially toxic gases are present in higher concentrations in sidestream smoke (the smoke that comes from the lighted end of the cigarette/pipe/cigar) than in mainstream smoke (smoke that is inhaled by a smoker and then exhaled into the environment) and nearly 85% of the smoke in a room results from sidestream smoke.4 The particulates in tobacco smoke include tar (itself composed of many chemicals), nicotine, benzene and benzo(a)pyrene. The gaseous component includes carbon monoxide, ammonia, dimethylnitrosamine, formaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide and acrolein. Some of these have marked irritant properties and there are more than 50 cancer-causing chemicals in secondhand smoke.5 For further information on tobacco smoke, please see ASH Fact Sheet: What’s in a Cigarette. Health effects Short-term effects of exposure to secondhand smoke (SHS) include eye irritation, headaches, coughs, sore throat, dizziness and nausea.