Floodplain Forests of Columbia and Dutchess Counties, NY: Distribution, Biodiversity, Classification, and Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 26, 2020 Via Electronic Mail Hon. Michelle L. Phillips, Secretary

August 26, 2020 Via Electronic Mail Hon. Michelle L. Phillips, Secretary New York State Board on Electric Generation Siting and the Environment 3 Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12223-1350 RE: Case No. 20-F-0048 – Application of Hecate Energy Columbia County 1, LLC for a Certificate of Environmental Compatibility and Public Need Pursuant to Article 10 of the Public Service Law for Construction of a Solar Electric Generating Facility Located in the Town of Copake, Columbia County. Shepherd’s Run Solar Dear Secretary Phillips: Pursuant to the Notice of Filing of Preliminary Scoping Statement and Deadline for Submitting Comments issued August 6, 2020, Scenic Hudson, Inc. (“Scenic Hudson”) respectfully submits the following comments on the Preliminary Scoping Statement (“PSS”) submitted in the above-referenced proceeding. Scenic Hudson’s Interest Scenic Hudson is a 501(c)(3) organization based in Poughkeepsie, New York. Scenic Hudson is dedicated to preserving the scenic, ecological, recreational, historic and agricultural treasures of the Hudson River valley. We combine land acquisition, support for agriculture, citizen-based advocacy and sophisticated planning tools to create environmentally healthy communities, champion smart economic growth, open up riverfronts to the public and preserve the valley’s inspiring beauty and natural resources. A crusader for the valley since 1963, today we are the largest environmental group focused on the Hudson River and its valley. We have over 25,000 supporters, the majority of which reside in the Hudson Valley region, including in Columbia County. The Scenic Hudson Land Trust, Inc. is an affiliate of Scenic Hudson, Inc. that owns lands throughout the Hudson Valley in fee and by conservation easement, including in Columbia County. -

Columbia Greene Trout Unlimited May 15Th Meeting Two DEC

Columbia Greene Trout Unlimited May 15th Meeting Two DEC conservation officers Jim Hayes and Jeff Cox held a Question and Answer session. After much discussion, it was evident that these guys are very dedicated. They are working as usual, though they have no contract, a depressed conservation fund and a hiring freeze. They are down 30 people in Region 4 and it takes 6 months to train and replace someone. They urged us to write letter to legislators and pressure them for funding 1. For new stocking vehicles and 2. For stream restoration. The meeting started at 8:11. The treasurer report: We have $6060- in is checking account. We have $1200 more coming in. The June meeting is changed to Sat. June 16th at 10:00. After a short meeting, we will fish the Roe Jan together. Location will be Bryant’s Farm. You can meet us at Dad’s restaurant in Copake N.Y. At 9:30 if you need help finding us. We will have a streamside cookout (hamburger and hot dog) around 1:00 PM. Our next Board of Directors meeting will be at Crosswinds in Hudson on June 12 at 6:30. All members are welcome TU national stream clean-up day is June 23rd. Vinnie is coordinating multi- group Greene Co stream clean up with the boy scouts, girl scouts, Agro- forestry (will do Catskill Creek) sportsmen, etc . Vinnie is waiting to hear from Kessler Insurance to make sure we have insurance for the stream clean- ups etc. Catskill Water Shed Corp will supply garbage bags for the event. -

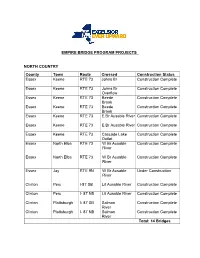

Empire Bridge Program Projects North Country

EMPIRE BRIDGE PROGRAM PROJECTS NORTH COUNTRY County Town Route Crossed Construction Status Essex Keene RTE 73 Johns Br Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 Johns Br Construction Complete Overflow Essex Keene RTE 73 Beede Construction Complete Brook Essex Keene RTE 73 Beede Construction Complete Brook Essex Keene RTE 73 E Br Ausable River Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 E Br Ausable River Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 Cascade Lake Construction Complete Outlet Essex North Elba RTE 73 W Br Ausable Construction Complete River Essex North Elba RTE 73 W Br Ausable Construction Complete River Essex Jay RTE 9N W Br Ausable Under Construction River Clinton Peru I-87 SB Lit Ausable River Construction Complete Clinton Peru I- 87 NB Lit Ausable River Construction Complete Clinton Plattsburgh I- 87 SB Salmon Construction Complete River Clinton Plattsburgh I- 87 NB Salmon Construction Complete River Total: 14 Bridges CAPITAL DISTRICT County Town Route Crossed Construction Status Warren Thurman Rte 28 Hudson River Construction Complete Washington Hudson Falls Rte 196 Glens Falls Construction Complete Feeder Canal Washington Hudson Falls Rte 4 Glens Falls Construction Complete Feeder Saratoga Malta Rte 9 Kayaderosseras Construction Complete Creek Saratoga Greenfield Rte 9n Kayaderosseras Construction Complete Creek Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Hoosick Rte -

2017 WRI Summary Report

NEW YORK STATE WATER RESOURCES INSTITUTE Department of Biological & Environmental Engineering 230 Riley-Robb Hall, Cornell University Tel: (607) 254-7163 Ithaca, NY 14853-5701 Fax: (607) 255-4080 http://wri.cals.cornell.edu Email: [email protected] Water Resource Infrastructure in New York: Assessment, Management, & Planning Prepared November 26, 2018 DRAFT – Water Resource Infrastructure in New York: Assessment, Management, & Planning – Year 6 The New York State Water Resources Institute (NYS 5) Environmental Policy & Socio-Economic Analysis - WRI), with funding from the United States Geological Integration of scientific, economic, Survey (USGS), and the New York State Department of planning/governmental and/or social expertise to Environmental Conservation (DEC) Hudson River build comprehensive strategies for public asset and Estuary Program (HREP) has undertaken a coordinated watershed management research effort on water resource infrastructure in New York State, with a focus on the Hudson and Mohawk Following this summary we also include: River basins. • A link to the full versions of final reports, which are available at our website The primary objective of this multi-year program is to http://wri.cals.cornell.edu/grants-funding bring innovative research and analysis to watershed • Outreach efforts currently underway planning and management. In particular, WRI-HREP is • How we are adapting our efforts to support research working to address the related topics of water and create effective outreach products infrastructure, environmental -

Spring 2019 Trout Stocking Summary

Mill Creek East Greenbush 440 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches SPRING 2019 TROUT STOCKING SUMMARY Poesten Kill Brunswick 2570 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Albany, Columbia, Rensselaer, Saratoga and Schenectady County Poesten Kill Brunswick 200 April Brown Trout 12 -15 inches Poesten Kill Brunswick 1420 May Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches WATER TOWN NUMBER DATE SPECIES SIZE Poesten Kill Poestenkill 300 April Brown Trout 12 -15 inches Poesten Kill Poestenkill 1560 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Albany County Poesten Kill Poestenkill 270 May Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Basic Creek Westerlo 440 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Poesten Kill Poestenkill 710 May - June Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Catskill Creek Rensselaerville 750 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Second Pond Grafton 440 June Brown Trout 8.5 - 9.5 inches Catskill Creek Rensselaerville 180 May Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Shaver Pond Grafton 600 Spring Rainbow Trout 8.5 - 9.5 inches Hannacrois Creek Coeymans 125 April Brown Trout 12 -15 inches Tackawasick Creek Nassau 100 April Brown Trout 12 -15 inches Hannacrois Creek Coeymans 1060 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Tackawasick Creek Nassau 800 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Hannacrois Creek Coeymans 710 May - June Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Tackawasick Creek Nassau 530 May - June Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Lisha Kill Colonie 350 March - April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Town Park Pond East Greenbush 500 April - May Rainbow Trout 8.5 - 9.5 inches Onesquethaw Creek New Scotland 1150 April Brown Trout 8 - 9 inches Walloomsac River Hoosick 500 April Brown Trout -

A Review of River and Stream Black Bass Data from the NY Stateweide

A REVIEW OF RIVER AND STREAM BLACK BASS DATA FROM THE NEW YORK STATEWIDE FISHERIES DATABASE 2004-2013 Photo by: Ryan Coulter, NYSDEC Jeff Loukmasa and Christian Perryb June 9, 2015 aBureau of Fisheries, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation bNew York Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Cornell University Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Methods........................................................................................................................................... 3 Results ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Survey categories ........................................................................................................................ 6 Gear types ................................................................................................................................... 7 Length by gear type .................................................................................................................... 9 Catch rates ................................................................................................................................. 11 Relative weight ........................................................................................................................ -

Ulster Orange Greene Dutchess Albany Columbia Schoharie

Barriers to Migratory Fish in the Hudson River Estuary Watershed, New York State Minden Glen Hoosick Florida Canajoharie Glenville Halfmoon Pittstown S a r a t o g a Schaghticoke Clifton Park Root Charleston S c h e n e c t a d y Rotterdam Frost Pond Dam Waterford Schenectady Zeno Farm Pond Dam Niskayuna Cherry Valley M o n t g o m e r y Duanesburg Reservoir Dam Princetown Fessenden Pond Dam Long Pond Dam Shaver Pond Dam Mill Pond Dam Petersburgh Duanesburg Hudson Wildlife Marsh DamSecond Pond Dam Cohoes Lake Elizabeth Dam Sharon Quacken Kill Reservoir DamUnnamed Lent Wildlife Pond Dam Delanson Reservoir Dam Masick Dam Grafton Lee Wildlife Marsh Dam Brunswick Martin Dunham Reservoir Dam Collins Pond Dam Troy Lock & Dam #1 Duane Lake Dam Green Island Cranberry Pond Dam Carlisle Esperance Watervliet Middle DamWatervliet Upper Dam Colonie Watervliet Lower Dam Forest Lake Dam Troy Morris Bardack Dam Wager Dam Schuyler Meadows Club Dam Lake Ridge Dam Beresford Pond Dam Watervliet rapids Ida Lake Dam 8-A Dyken Pond Dam Schuyler Meadows Dam Mt Ida Falls Dam Altamont Metal Dam Roseboom Watervliet Reservoir Dam Smarts Pond Dam dam Camp Fire Girls DamUnnamed dam Albia Dam Guilderland Glass Pond Dam spillway Wynants Kill Walter Kersch Dam Seward Rensselaer Lake Dam Harris Dam Albia Ice Pond Dam Altamont Main Reservoir Dam West Albany Storm Retention Dam & Dike 7-E 7-F Altamont Reservoir Dam I-90 Dam Sage Estates Dam Poestenkill Knox Waldens Pond DamBecker Lake Dam Pollard Pond Dam Loudonville Reservoir Dam John Finn Pond Dam Cobleskill Albany Country Club Pond Dam O t s e g o Schoharie Tivoli Lake Dam 7-A . -

Natural Areas and Wildlife in Your Community a Habitat Summary Prepared for the Town of Copake March 2014

Natural Areas and Wildlife in Your Community A Habitat Summary Prepared for the Town of Copake March 2014 This summary was completed to provide information for land-use planning and decision-making as requested by the Town of Copake. It identifies significant ecosystems in the town, including streams, forests, wetlands, and other natural areas with important biological values. This summary is based only on existing information available to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and its partners, and, therefore should not be considered a complete inventory. Additional information about habitats in our region can be found in the Wildlife and Habitat Conservation Framework developed by the Hudson River Estuary Program (Penhollow et al. 2006) and in the Biodiversity Assessment Manual for the Hudson River Estuary Corridor developed by Hudsonia and published by NYSDEC (Kiviat and Stevens 2001). Ecosystems of the estuary watershed—wetlands, forests, stream corridors, grasslands, and shrublands— are not only habitat for abundant fish and wildlife, but also support the estuary and provide many vital benefits to human communities. These ecosystems help to keep drinking water and air clean, moderate temperature, filter pollutants, and absorb floodwaters. They also provide opportunity for outdoor recreation and education, and create the scenery and sense of place that is unique to the Hudson Valley. Local land-use planning efforts are instrumental in balancing future development with protection of these resources. By conserving sufficient habitat to support the region’s astonishing diversity of plants and animals, communities can ensure that healthy, resilient ecosystems—and the benefits they provide—are available to future generations. -

Hudson Valley Region: Health Advice on Eating Fish You Catch

Hudson Valley MAPS Region INSIDE Health Advice on Eating Fish You Catch Including Albany, Columbia, Dutchess, Greene, Orange, Putnam, Rensselaer, Rockland, Saratoga, Schenectady, Ulster, Washington, and Westchester Counties Why We Have Advice Chemicals in the Hudson Valley Region Fishing is fun and fish are an important part of a healthy diet. Fish contain high quality The primary chemicals of concern in the Hudson Valley Region are PCBs and mercury. protein, essential nutrients, healthy fish oils, and are low in saturated fat. However, A few waterbodies have chlordane, dieldrin, dioxin, cadmium and PFCs. some fish contain chemicals at levels that may be harmful to health. To help people make healthier choices about which fish they eat, the New York State Department of Health • PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), chlordane, and dieldrin are man-made issues advice about eating sportfish (fish you catch). The health advice about which fish chemicals that were banned in the 1970s and 1980s. Dioxins are byproducts to eat depends on: released by a number of activities, including burning of trash, wood fires, and manufacturing. PCBs, chlordane, dieldrin, and dioxin remain in the Where You Fish environment and accumulate in the fat of fish and other animals. The advice on eating fish from the Hudson Valley Region depends • Mercury occurs naturally, but it is also released into our environment from upon where you fish. The region has great fishing and many waters sources like coal combustion. Testing of fish in the Adirondack and Catskill where everyone in the family can eat up to four fish meals a month. Regions and in some NYS reservoirs has shown certain species of fish have However, some waters and their tributaries have been affected higher levels of mercury than in other parts of the state. -

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Hudson River Estuary Program, Biodiversity Outreach 625 Broadway, 5th Floor; Albany, NY 12233-4750 Phone: (518) 402-8878 • FAX: (518) 402-8925 Website: www.dec.ny.gov Peter M. Iwanowicz Acting Commissioner To: Town of Hillsdale Conservation Advisory Council From: Karen Strong, Hudson River Estuary Biodiversity Outreach Coordinator, 518-402-8878, [email protected] Re: Town of Hillsdale Habitat Summary Date: November 2010 Background This summary was completed upon request to provide information for the Town of Hillsdale for use in land use planning and decision-making. It identifies major natural features, as well as important stream, forest, wetland, and other habitats with important biological resources based on information available to the NYSDEC. Because it is based only on existing information, it should not be considered a complete biological resource inventory. In the case of Hillsdale, few biological surveys have been completed, therefore little is known about the occurrence of plants and animals of conservation concern. Additional general information can be found in the Wildlife and Habitat Conservation Framework developed by the Hudson River Estuary Program (Penhollow et al. 2006). If you have any questions about this summary, or want to know if it needs to be updated, please contact Karen Strong, Biodiversity Outreach Coordinator. NYSDEC’s Hudson River Estuary Program protects and improves the historic and scenic Hudson River watershed for all its residents. The program was created in 1987 and extends from the Troy dam to the Verrazano Narrows. Its core mission is to: • Ensure clean water; • Protect and restore fish and wildlife habitats; • Provide recreation in and on the water; • Adapt to climate change; and • Conserve the scenic landscape. -

Discovery Report Appendix H Discovery Meeting Summary Memorandum Mid-Hudson Watershed HUC 02020006

Discovery Report Appendix H Discovery Meeting Summary Memorandum Mid-Hudson Watershed HUC 02020006 June 2017 Federal Emergency Management Agency Department of Homeland Security 26 Federal Plaza New York, NY Memorandum To: Mid-Hudson Watershed Discovery Project File From: NYSDEC Floodplain Management Section Date: June 2017 Re: Mid-Hudson Watershed Discovery Meeting Summary Two initial Pre-Discovery webinars were held for all stakeholders within the Mid-Hudson Watershed on May 10, 2016 and May 11, 2016. The purpose of these webinars was to: introduce watershed stakeholders to Risk MAP Discovery project concepts; review the Discovery Stakeholder Survey to be completed by watershed stakeholders; the survey served as a way for FEMA and NYSDEC to collect information upfront on communities mapping needs and existing data that could be incorporated into a possible Risk MAP project; and to discuss upcoming timelines for future Discovery Meetings and the Discovery project overall. Five Risk MAP Discovery Meetings were held in the Mid-Hudson Watershed during the week of October 17, 2016. The purpose of the Discovery Meetings was to present the draft Discovery Report and Maps containing the information collected to date, and to provide the communities with an additional opportunity for input. This memo is a summary of the information collected through the Discovery project engagement process for the Mid-Hudson Watershed and will be used to determine the floodplain mapping restudy priorities. Albany County, CID# 36001C Pre- Discovery Webinar Attendance: Attended Discovery Stakeholder Survey Completed: June 5, 2016, October 19, 2016 Discovery Meeting Attendance: October 19, 2016 Community Representative(s): Lee Bormann, Critical Incident Emergency Management Unit Commander (Survey and Meeting) Albany County Sheriff Office 58 Verda Avenue Clarksville, NY 12041 518-720-8025 [email protected] Peter Bayzon, Natural Resource Specialist (Meeting) Albany County Soil and Water Conservation District P.O. -

Regional Economic Development Council Plans

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo Regional EconomicAwards Development Council 2016 1 Table of Contents Regional Council Awards Western New York .........................................................................................................................10 Finger Lakes ...................................................................................................................................24 Southern Tier ..................................................................................................................................36 Central New York ..........................................................................................................................44 Mohawk Valley ...............................................................................................................................56 North Country .................................................................................................................................68 Capital Region ................................................................................................................................80 Mid-Hudson .....................................................................................................................................96 New York City ................................................................................................................................ 112 Long Island ...................................................................................................................................