Columbia Land Conservancy 2018 Natural Resources Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 26, 2020 Via Electronic Mail Hon. Michelle L. Phillips, Secretary

August 26, 2020 Via Electronic Mail Hon. Michelle L. Phillips, Secretary New York State Board on Electric Generation Siting and the Environment 3 Empire State Plaza Albany, New York 12223-1350 RE: Case No. 20-F-0048 – Application of Hecate Energy Columbia County 1, LLC for a Certificate of Environmental Compatibility and Public Need Pursuant to Article 10 of the Public Service Law for Construction of a Solar Electric Generating Facility Located in the Town of Copake, Columbia County. Shepherd’s Run Solar Dear Secretary Phillips: Pursuant to the Notice of Filing of Preliminary Scoping Statement and Deadline for Submitting Comments issued August 6, 2020, Scenic Hudson, Inc. (“Scenic Hudson”) respectfully submits the following comments on the Preliminary Scoping Statement (“PSS”) submitted in the above-referenced proceeding. Scenic Hudson’s Interest Scenic Hudson is a 501(c)(3) organization based in Poughkeepsie, New York. Scenic Hudson is dedicated to preserving the scenic, ecological, recreational, historic and agricultural treasures of the Hudson River valley. We combine land acquisition, support for agriculture, citizen-based advocacy and sophisticated planning tools to create environmentally healthy communities, champion smart economic growth, open up riverfronts to the public and preserve the valley’s inspiring beauty and natural resources. A crusader for the valley since 1963, today we are the largest environmental group focused on the Hudson River and its valley. We have over 25,000 supporters, the majority of which reside in the Hudson Valley region, including in Columbia County. The Scenic Hudson Land Trust, Inc. is an affiliate of Scenic Hudson, Inc. that owns lands throughout the Hudson Valley in fee and by conservation easement, including in Columbia County. -

Hudson River Watershed 2002 Water Quality Assessment Report

HUDSON RIVER WATERSHED 2002 WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT REPORT COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS EXECUTIVE OFFICE OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS ROBERT W. GOLLEDGE, JR, SECRETARY MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION ARLEEN O’DONNELL, ACTING COMMISSIONER BUREAU OF RESOURCE PROTECTION GLENN HAAS, ACTING ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER DIVISION OF WATERSHED MANAGEMENT GLENN HAAS, DIRECTOR NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY LIMITED COPIES OF THIS REPORT ARE AVAILABLE AT NO COST BY WRITTEN REQUEST TO: MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION DIVISION OF WATERSHED MANAGEMENT 627 MAIN STREET WORCESTER, MA 01608 This report is also available from the MassDEP’s home page on the World Wide Web at: http://www.mass.gov/dep/water/resources/wqassess.htm Furthermore, at the time of first printing, eight copies of each report published by this office are submitted to the State Library at the State House in Boston; these copies are subsequently distributed as follows: · On shelf; retained at the State Library (two copies); · Microfilmed retained at the State Library; · Delivered to the Boston Public Library at Copley Square; · Delivered to the Worcester Public Library; · Delivered to the Springfield Public Library; · Delivered to the University Library at UMass, Amherst; · Delivered to the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Moreover, this wide circulation is augmented by inter-library loans from the above-listed libraries. For example a resident in Marlborough can apply at their local library for loan of any MassDEP/DWM report from the Worcester Public Library. A complete list of reports published since 1963 is updated annually and printed in July. This report, entitled, “Publications of the Massachusetts Division of Watershed Management – Watershed Planning Program, 1963-(current year)”, is also available by writing to the Division of Watershed Management (DWM) in Worcester. -

New York Freshwater Fishing Regulations Guide: 2015-16

NEW YORK Freshwater FISHING2015–16 OFFICIAL REGULATIONS GUIDE VOLUME 7, ISSUE NO. 1, APRIL 2015 Fishing for Muskie www.dec.ny.gov Most regulations are in effect April 1, 2015 through March 31, 2016 MESSAGE FROM THE GOVERNOR New York: A State of Angling Opportunity When it comes to freshwater fishing, no state in the nation can compare to New York. Our Great Lakes consistently deliver outstanding fishing for salmon and steelhead and it doesn’t stop there. In fact, New York is home to four of the Bassmaster’s top 50 bass lakes, drawing anglers from around the globe to come and experience great smallmouth and largemouth bass fishing. The crystal clear lakes and streams of the Adirondack and Catskill parks make New York home to the very best fly fishing east of the Rockies. Add abundant walleye, panfish, trout and trophy muskellunge and northern pike to the mix, and New York is clearly a state of angling opportunity. Fishing is a wonderful way to reconnect with the outdoors. Here in New York, we are working hard to make the sport more accessible and affordable to all. Over the past five years, we have invested more than $6 million, renovating existing boat launches and developing new ones across the state. This is in addition to the 50 new projects begun in 2014 that will make it easier for all outdoors enthusiasts to access the woods and waters of New York. Our 12 DEC fish hatcheries produce 900,000 pounds of fish each year to increase fish populations and expand and improve angling opportunities. -

Columbia Greene Trout Unlimited May 15Th Meeting Two DEC

Columbia Greene Trout Unlimited May 15th Meeting Two DEC conservation officers Jim Hayes and Jeff Cox held a Question and Answer session. After much discussion, it was evident that these guys are very dedicated. They are working as usual, though they have no contract, a depressed conservation fund and a hiring freeze. They are down 30 people in Region 4 and it takes 6 months to train and replace someone. They urged us to write letter to legislators and pressure them for funding 1. For new stocking vehicles and 2. For stream restoration. The meeting started at 8:11. The treasurer report: We have $6060- in is checking account. We have $1200 more coming in. The June meeting is changed to Sat. June 16th at 10:00. After a short meeting, we will fish the Roe Jan together. Location will be Bryant’s Farm. You can meet us at Dad’s restaurant in Copake N.Y. At 9:30 if you need help finding us. We will have a streamside cookout (hamburger and hot dog) around 1:00 PM. Our next Board of Directors meeting will be at Crosswinds in Hudson on June 12 at 6:30. All members are welcome TU national stream clean-up day is June 23rd. Vinnie is coordinating multi- group Greene Co stream clean up with the boy scouts, girl scouts, Agro- forestry (will do Catskill Creek) sportsmen, etc . Vinnie is waiting to hear from Kessler Insurance to make sure we have insurance for the stream clean- ups etc. Catskill Water Shed Corp will supply garbage bags for the event. -

Hydrogeology of the Schodack-Kinderhook Area, Rensselaer and Columbia Counties, New York

Hydrogeology of the Schodack-Kinderhook Area, Rensselaer and Columbia Counties, New York U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 97-639 Prepared in cooperation with NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION Cover: View of Moordener Kill from State Rt. 150 in Brookview, N.Y., looking west (downstream). Note exposed bedrock in streambed. (Photo by R.J. Reynolds, 1999). Hydrogeology of the Schodack-Kinderhook Area, Rensselaer and Columbia Counties, New York By Richard J. Reynolds ______________________________________________________________ U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 97-639 Prepared in cooperation with the NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION science for a changing world Troy, New York 1999 i U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director ______________________________________________________________________ For additional information Copies of this report may be write to: purchased from: U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey 425 Jordan Road Branch of Information Services Troy, NY 12180-8349 P.O. Box 25286 Denver, CO 80225 ii CONTENTS Abstract ................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Purpose and Scope ......................................................................................................................................................... -

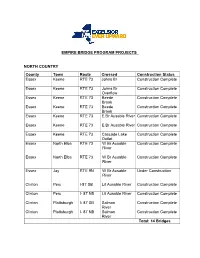

Empire Bridge Program Projects North Country

EMPIRE BRIDGE PROGRAM PROJECTS NORTH COUNTRY County Town Route Crossed Construction Status Essex Keene RTE 73 Johns Br Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 Johns Br Construction Complete Overflow Essex Keene RTE 73 Beede Construction Complete Brook Essex Keene RTE 73 Beede Construction Complete Brook Essex Keene RTE 73 E Br Ausable River Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 E Br Ausable River Construction Complete Essex Keene RTE 73 Cascade Lake Construction Complete Outlet Essex North Elba RTE 73 W Br Ausable Construction Complete River Essex North Elba RTE 73 W Br Ausable Construction Complete River Essex Jay RTE 9N W Br Ausable Under Construction River Clinton Peru I-87 SB Lit Ausable River Construction Complete Clinton Peru I- 87 NB Lit Ausable River Construction Complete Clinton Plattsburgh I- 87 SB Salmon Construction Complete River Clinton Plattsburgh I- 87 NB Salmon Construction Complete River Total: 14 Bridges CAPITAL DISTRICT County Town Route Crossed Construction Status Warren Thurman Rte 28 Hudson River Construction Complete Washington Hudson Falls Rte 196 Glens Falls Construction Complete Feeder Canal Washington Hudson Falls Rte 4 Glens Falls Construction Complete Feeder Saratoga Malta Rte 9 Kayaderosseras Construction Complete Creek Saratoga Greenfield Rte 9n Kayaderosseras Construction Complete Creek Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Nassau Rte 20 Kinderhook Creek Construction Complete Rensselaer Hoosick Rte -

Distribution of Ddt, Chlordane, and Total Pcb's in Bed Sediments in the Hudson River Basin

NYES&E, Vol. 3, No. 1, Spring 1997 DISTRIBUTION OF DDT, CHLORDANE, AND TOTAL PCB'S IN BED SEDIMENTS IN THE HUDSON RIVER BASIN Patrick J. Phillips1, Karen Riva-Murray1, Hannah M. Hollister2, and Elizabeth A. Flanary1. 1U.S. Geological Survey, 425 Jordan Road, Troy NY 12180. 2Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Troy NY 12180. Abstract Data from streambed-sediment samples collected from 45 sites in the Hudson River Basin and analyzed for organochlorine compounds indicate that residues of DDT, chlordane, and PCB's can be detected even though use of these compounds has been banned for 10 or more years. Previous studies indicate that DDT and chlordane were widely used in a variety of land use settings in the basin, whereas PCB's were introduced into Hudson and Mohawk Rivers mostly as point discharges at a few locations. Detection limits for DDT and chlordane residues in this study were generally 1 µg/kg, and that for total PCB's was 50 µg/kg. Some form of DDT was detected in more than 60 percent of the samples, and some form of chlordane was found in about 30 percent; PCB's were found in about 33 percent of the samples. Median concentrations for p,p’- DDE (the DDT residue with the highest concentration) were highest in samples from sites representing urban areas (median concentration 5.3 µg/kg) and lower in samples from sites in large watersheds (1.25 µg/kg) and at sites in nonurban watersheds. (Urban watershed were defined as those with a population density of more than 60/km2; nonurban watersheds as those with a population density of less than 60/km2, and large watersheds as those encompassing more than 1,300 km2. -

Flood Resilience Education in the Hudson River Estuary: Needs Assessment and Program Evaluation

NEW YORK STATE WATER RESOURCES INSTITUTE Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences 1123 Bradfield Hall, Cornell University Tel: (607) 255-3034 Ithaca, NY 14853-1901 Fax: (607) 255-2016 http://wri.eas.cornell.edu Email: [email protected] Flood Resilience Education in the Hudson River Estuary: Needs Assessment and Program Evaluation Shorna Allred Department of Natural Resources (607) 255-2149 [email protected] Gretchen Gary Department of Natural Resources (607) 269-7859 [email protected] Catskill Creek at Woodstock Dam during low flow (L) and flood conditions (R) Photo Credit - Elizabeth LoGiudice Abstract In recent decades, very heavy rain events (the heaviest 1% of all rain events from 1958-2012) have increased in frequency by 71% in the Northeast U.S. As flooding increases, so does the need for flood control Decisions related to flood control are the responsibility of many individuals and groups across the spectrum of a community, such as local planners, highway departments, and private landowners. Such decisions include strategies to minimize future Flood Resilience Education in the Hudson River Estuary: Needs Assessment and Program Evaluation flooding impacts while also properly responding to storm impacts to streams and adjacent and associated infrastructure. This project had three main components: 1) a flood education needs assessment of local municipal officials (2013), 2) an evaluation of a flood education program for highway personnel (2013), and 3) a survey of riparian landowners (2014). The riparian landowner needs assessment determined that the majority of riparian landowners in the region have experienced flooding, yet few are actually engaging in stream management to mitigate flood issues on their land. -

HUDSON VALLEY REGION Columbia County

HUDSON VALLEY REGION Columbia County. The long unwinding road. Take a drive along our country roads and you’ll step back in time to another era. Where the livin’ is easy. Where you can enjoy the best of cultural and historical sites and attractions. Or not, your choice. Where a country store offers fresh produce and baked goods, and a you-can-pay-me- tomorrow attitude. Where “laid back” isn’t just a label, but a lifestyle. Best of all, wherever you wander in our fair county—to shop, hear music, dine, or just explore—you’ll meander along some of best country roads in America. www.bestcountryroads.com 1 Seeing & Doing Seeing & Doing The Arts Living History More and more, Columbia County is the cultural Columbia County offers life’s simple gifts in a gem of the Hudson Valley. Here in a bucolic setting place that’s simply historic. you can view provocative works from international Start with a jewel of Columbia County architecture: and regional artists. Avant-garde painting and Olana—the masterstroke of Frederic Church, sculpture. Exhilarating musicals. And classical one of America’s premier landscape painters. concerts of every size and shape. His Persian-style mansion offers sweeping views Here, renowned artists, inspired by tranquility, of the Hudson that will take your breath away. make their home, following in the footsteps of Head down to Clermont, the 18th century manor Frederic Church, Thomas Cole, Sanford Gifford home, and celebrate Clermont’s Fulton-Livingston and other painters of the Hudson River school. steamboat bicentennial in 2007. Wander through Today, galleries dot the country and grace our the Federal mansion of James Vanderpoel, whose towns and villages. -

Watershed Stewardship Program Summary of Programs and Research 2010

Watershed Stewardship Program Summary of Programs and Research 2010 Adirondack Watershed Institute Watershed Stewardship Program Report # AWI 2011-02 2 Watershed Stewardship Program Summary of Programs and Research 2010 Table of Contents Executive Summary and Introduction ...................................................................................................... 3 Watershed Stewardship Program- Staff Profiles .................................................................................... 10 Recreation Use Study: Lake Placid State Boat Launch ............................................................................ 13 Recreation Use Study: Osgood Pond ...................................................................................................... 29 Recreation Use Study: Rainbow Lake ..................................................................................................... 35 Recreation Use Study: Saratoga Lake State Boat Launch ........................................................................ 44 Recreation Use Study: Second Pond/Lower Saranac Lake ...................................................................... 55 Recreation Use Study: St. Regis Lakes .................................................................................................... 65 Recreation Use Study: Tupper Lake ....................................................................................................... 73 Fragment viability and rootlet formation in Eurasian watermilfoil after desiccation .............................. -

Chittenden Falls Hydroelectric Project FERC Project No

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR HYDROPOWER LICENSE Chittenden Falls Hydroelectric Project FERC Project No. 3273-024 New York Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Office of Energy Projects Division of Hydropower Licensing 888 First Street, NE Washington, D.C. 20426 January 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... xii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ xiii ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ......................................................................... xiv 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Application .................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of Action and Need For Power ........................................................ 2 1.2.1 Purpose of Action ............................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Need for Power ................................................................................ 4 1.3 Statutory and Regulatory Requirements ....................................................... 4 1.4 Public Review and Comment ........................................................................ 4 1.4.1 Scoping ............................................................................................ 4 1.4.2 Interventions ................................................................................... -

2017 WRI Summary Report

NEW YORK STATE WATER RESOURCES INSTITUTE Department of Biological & Environmental Engineering 230 Riley-Robb Hall, Cornell University Tel: (607) 254-7163 Ithaca, NY 14853-5701 Fax: (607) 255-4080 http://wri.cals.cornell.edu Email: [email protected] Water Resource Infrastructure in New York: Assessment, Management, & Planning Prepared November 26, 2018 DRAFT – Water Resource Infrastructure in New York: Assessment, Management, & Planning – Year 6 The New York State Water Resources Institute (NYS 5) Environmental Policy & Socio-Economic Analysis - WRI), with funding from the United States Geological Integration of scientific, economic, Survey (USGS), and the New York State Department of planning/governmental and/or social expertise to Environmental Conservation (DEC) Hudson River build comprehensive strategies for public asset and Estuary Program (HREP) has undertaken a coordinated watershed management research effort on water resource infrastructure in New York State, with a focus on the Hudson and Mohawk Following this summary we also include: River basins. • A link to the full versions of final reports, which are available at our website The primary objective of this multi-year program is to http://wri.cals.cornell.edu/grants-funding bring innovative research and analysis to watershed • Outreach efforts currently underway planning and management. In particular, WRI-HREP is • How we are adapting our efforts to support research working to address the related topics of water and create effective outreach products infrastructure, environmental