Wirral Revisited University of the West of England, Bristol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting Model

LANDFIRE Biophysical Setting Model Biophysical Setting 7316170 Western North American Boreal Shrub and Herbaceous Floodplain Wetland This BPS is lumped with: This BPS is split into multiple models: General Information Contributors (also see the Comments field Date 5/7/2008 Modeler 1 Tina Boucher [email protected] Reviewer Michelle Schuman michelle.schuman@a k.usda.gov Modeler 2 Kori Blankenship [email protected] Reviewer Modeler 3 Colleen Ryan [email protected] Reviewer Vegetation Type Map Zone Model Zone Wetlands/Riparian 73 Alaska N-Cent.Rockies California Pacific Northwest Dominant Species* General Model Sources Great Basin South Central Literature METR3 ERAN6 Great Lakes Southeast Local Data CAAQ MYGA Northeast S. Appalachians EQFL BENA Expert Estimate Northern Plains Southwest COPA28 CHCA2 Geographic Range This system is found throughout the boreal and sub-boreal regions. It occurs within the floodplain boundaries of the Western North American Boreal Montane Floodplain Forest and Shrubland - Boreal, Western North American Boreal Lowland Large River Floodplain Forest and Shrubland and Western North American Boreal Montane Floodplain Forest and Shrubland - Alaska Sub-boreal. Biophysical Site Description The following information was taken from the draft Boreal Ecological Systems description (NatureServe 2008): Floodplain wetlands occur within the active and inactive portions of floodplain systems. Wetlands develop on poorly drained deposits, oxbows and abandoned channels and are often mosaiced with well- drained floodplain vegetation. Vegetation Description Species composition is variable due to diverse environmental conditions such as water depth, substrate and nutrient input, as well as seral stage. Aquatic bed, marsh and fen communities are common. The earliest seral stages (aquatic bed) have aquatic vegetation such as Nuphar polysepala. -

Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Fruit Essential Oils of Myrica Gale, a Neglected Non-Wood Forest Product

BALTIC FORESTRY http://www.balticforestry.mi.lt Baltic Forestry 2020 26(1): 13–20 ISSN 1392-1355 Category: research article eISSN 2029-9230 https://doi.org/10.46490/BF423 Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of fruit essential oils of Myrica gale, a neglected non-wood forest product KRISTINA LOŽIENĖ1,2, JUOZAS LABOKAS1*, VAIDA VAIČIULYTĖ1, JURGITA ŠVEDIENĖ1, VITA RAUDONIENĖ1, ALGIMANTAS PAŠKEVIČIUS1, LAIMA ŠVEISTYTĖ3 AND VIOLETA APŠEGAITĖ1 1 Nature Research Centre, Akademijos g. 2, LT-08412 Vilnius, Lithuania 2 Farmacy Center, Institute of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Medicine, Vilnius University, M.K. Čiurlionio g. 21/27, LT-03101 Vilnius, Lithuania 3 Plant Gene Bank, Stoties g. 2, Akademija, LT-58343 Kėdainių r., Lithuania * Corresponding author: [email protected], phone: +370 5 2729930 Ložienė, K., Labokas, J., Vaičiulytė, V., Švedienė, J., Raudonienė, V., Paškevičius, A., Šveistytė, L. and Apšegaitė, V. 2020. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of fruit essential oils of Myrica gale, a neglected non-wood forest product. Baltic Forestry 26(1): 13–20. https://doi.org/10.46490/BF423. Received 18 October 2019 Revised 25 March 2020 Accepted 28 April 2020 Abstract The study aimed to establish the chemical composition of fruit essential oils of M. gale and test their activities against the selected pathogenic bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumannii), yeasts (Candida albicans, C. parapsilosis), fungi (Aspergillus fumigatus, A. flavus) and dermatophytes (Trichophyton rubrum, T. mentagrophytes). Fruit samples from natural (Western Lithuania) and anthropogenic (Eastern Lithuania) M. gale populations were studied separately. Essential oils were isolated from dried fruits by hydrodistillation and analysed by GC/FID and GC/MS methods; enantiomeric composition of α-pinene was established by chiral-phase capillary GC. -

Wrightmarshall.Co.Uk Fineandcountry.Com

QUOISLEY BRIDGE HOUSE | QUOISLEY BRIDGE | WHITCHURCH | SY13 4HG GUIDE PRICE £500,000 COUNTRY HOMES │ COTTAGES │ UNIQUE PROPERTIES │ CONVERSIONS │ PERIOD PROPERTIES │ LUXURY APARTMENTS wrightmarshall.co.uk fineandcountry.com 'Quoisley Bridge House', Quoisley Bridge, Whitchurch, Cheshire, SY13 4HG Quoisley Bridge House is a magnificent Four Bedroom, Two Bathroom, Detached Character Country Residence, offering just over 3 acres of splendid gardens, orchard & grazing land with detached stables, garage & small barn, adjoining countryside. The spacious accommodation comprises: Entrance Hall, Snug, Conservatory, Formal Dining Room, Kitchen open to Dining/Family Room, Utility, WC, Drawing Room. First Floor Landing: Master Bedroom One, Dressing Area & Ensuite, Bedroom Two, Bedrooms Three & Four, Bath & Shower Room, Separate WC. Electric gates & approx 60 metre drive leads to the property. Magnificent parkland-style gardens with beautiful ornamental pond, orchard & grazing land, all enjoying complete privacy. Reception Hall / Snug DIRECTIONS Proceed from Nantwich along Welsh Row (A51) to AGENTS NOTE:- 'Quoisley Bridge House' is a most impressive Acton. Turn left at St Marys Church into Monks Lane & proceed detached country residence situated adjoining magnificent open through Burland village. At the main A49 junction, turn left onto the countryside. The current owners have beautifully enhanced the A49 itself passing the Cholmondeley Arms Public House. After approx property which combines charm & character with modern 3.5 miles, the property will be observed on the left hand side, marked conveniences, whilst having a most engaging garden setting. For by our 'For Sale' boards. prospective purchasers simply wishing to live the 'good life', of an equestrian or horticultural persuasion, this property is ideal for a wide QUOISELEY BRIDGE Quoisley Bridge is a rural, predominantly range of requirements. -

New Additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives

Cumbria Archive Service CATALOGUE: new additions August 2021 Carlisle Archive Centre The list below comprises additions to CASCAT from Carlisle Archives from 1 January - 31 July 2021. Ref_No Title Description Date BRA British Records Association Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Moor, yeoman to Ranald Whitfield the son and heir of John Conveyance of messuage and Whitfield of Standerholm, Alston BRA/1/2/1 tenement at Clargill, Alston 7 Feb 1579 Moor, gent. Consideration £21 for Moor a messuage and tenement at Clargill currently in the holding of Thomas Archer Thomas Archer of Alston Moor, yeoman to Nicholas Whitfield of Clargill, Alston Moor, consideration £36 13s 4d for a 20 June BRA/1/2/2 Conveyance of a lease messuage and tenement at 1580 Clargill, rent 10s, which Thomas Archer lately had of the grant of Cuthbert Baynbrigg by a deed dated 22 May 1556 Ranold Whitfield son and heir of John Whitfield of Ranaldholme, Cumberland to William Moore of Heshewell, Northumberland, yeoman. Recites obligation Conveyance of messuage and between John Whitfield and one 16 June BRA/1/2/3 tenement at Clargill, customary William Whitfield of the City of 1587 rent 10s Durham, draper unto the said William Moore dated 13 Feb 1579 for his messuage and tenement, yearly rent 10s at Clargill late in the occupation of Nicholas Whitfield Thomas Moore of Clargill, Alston Moor, yeoman to Thomas Stevenson and John Stevenson of Corby Gates, yeoman. Recites Feb 1578 Nicholas Whitfield of Alston Conveyance of messuage and BRA/1/2/4 Moor, yeoman bargained and sold 1 Jun 1616 tenement at Clargill to Raynold Whitfield son of John Whitfield of Randelholme, gent. -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Early Methodism in and Around Chester, 1749-1812

EARIvY METHODISM IN AND AROUND CHESTER — Among the many ancient cities in England which interest the traveller, and delight the antiquary, few, if any, can surpass Chester. Its walls, its bridges, its ruined priory, its many churches, its old houses, its almost unique " rows," all arrest and repay attention. The cathedral, though not one of the largest or most magnificent, recalls many names which deserve to be remembered The name of Matthew Henry sheds lustre on the city in which he spent fifteen years of his fruitful ministry ; and a monument has been most properly erected to his honour in one of the public thoroughfares, Methodists, too, equally with Churchmen and Dissenters, have reason to regard Chester with interest, and associate with it some of the most blessed names in their briefer history. ... By John Wesley made the head of a Circuit which reached from Warrington to Shrewsbury, it has the unique distinction of being the only Circuit which John Fletcher was ever appointed to superintend, with his curate and two other preachers to assist him. Probably no other Circuit in the Connexion has produced four preachers who have filled the chair of the Conference. But from Chester came Richard Reece, and John Gaulter, and the late Rev. John Bowers ; and a still greater orator than either, if not the most effective of all who have been raised up among us, Samuel Bradburn. (George Osborn, D.D. ; Mag., April, 1870.J Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/earlymethodisminOObretiala Rev. -

South Cheshire Way A4

CONTENTS The Mid-Cheshire Footpath Society Page Waymarked Walks in Central Cheshire About the South Cheshire Way 3 Using this guide (including online map links) 6 Points of interest 9 Congleton Sandbach Mow Walking eastwards 15 Cop Grindley Brook to Marbury Big Mere 17 Scholar Green Biddulph Marbury Big Mere to Aston Village 21 Crewe Aston Village to River Weaver 24 River Weaver to A51 by Lea Forge 26 Nantwich Kidsgrove A51 by Lea Forge to Weston Church 29 Weston Church to Haslington Hall 33 Haslington Hall to Thurlwood 37 Thurlwood to Little Moreton Hall (A34) 41 Little Moreton Hall (A34) to Mow Cop 43 Stoke on Trent Grindley Brook Audlem Walking westwards 45 Mow Cop to Little Moreton Hall (A34) 47 Whitchurch Little Moreton Hall (A34) to Thurlwood 49 Thurlwood to Haslington Hall 51 Haslington Hall to Weston Church 55 Weston Church to A51 by Lea Forge 59 A51 by Lea Forge to River Weaver 63 River Weaver to Aston Village 66 THE SOUTH CHESHIRE WAY Aston Village to Marbury Big Mere 69 Marbury Big Mere to Grindley Brook 73 From Grindley Brook to Mow Cop Update information (Please read before walking) 77 About The Mid-Cheshire Footpath Society 78 A 55km (34 mile) walk in the Cheshire countryside. South Cheshire Way Page 2 of 78 Links with other footpaths ABOUT THE SOUTH CHESHIRE WAY There are excellent links with other long distance footpaths at either end. At Grindley Brook there are links with the 'Shropshire Way', the 'Bishop Bennet Bridleway', the 'Sandstone Trail', the 'Maelor Way' and the (now The South Cheshire Way was originally conceived as a route in the late unsupported) 'Marches Way'. -

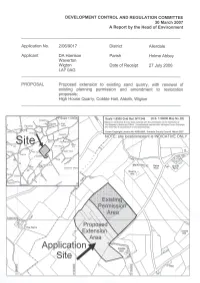

(Item 9) Application No. 2-06-9017 High House Quarry, Cobble Hall

1.0 RECOMMENDATION 1.1 That having regard to the environmental information planning permission be GRANTED for the reasons set out in Appendix 1 and subject to: (a) The execution of an agreement under Section 106 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 to: (i) secure the proposed voluntary HGV routing agreement and ‘Haulier Rules’ which all the applicant’s drivers and haulage contractors are required to abide by; (ii) secure a contribution of £10,000 from the applicant to the Council which shall be applied by the Council to mitigate the impacts of HGV traffic and provide local highway improvements; (iii) secure the route of an access along the Abbeytown ridge top on land in the applicants ownership for recreational use. (b) The conditions in Appendix 2. 1.2 That the planning assessment set out in section 4 of the report shall form the basis of the statutory requirement to be published under Regulation 21 of the Town and Country Planning Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations 1999. 2.0 THE PROPOSAL 2.1 The applicant seeks to extend the life of an existing permission Ref. 2/01/9043 which expired on 31 December 2006 and extend the area of the sand quarry to the west by a further 10.7 hectares making a total site area of 19.6 hectares. 2.2 The High House Quarry is located at the eastern end of the fluvio-glacial sand ridge called the Abbeytown Ridge. Sand has been extracted from the area for 40 years and High House Quarry has been worked for 20 years in association with Aldoth and Dixon Hill Quarries, which are now worked out. -

Display PDF in Separate

V nvironment agency plan EDEN, ESK & SOLWAY ENVIRONMENTAL OVERVIEW SEPTEMBER 1999 ▼ ▼ E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y ▼ DATE DUE - / a n o | E n v ir o n m e n t A g e n c y / iZ /D l/O 'if NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION/SERVICE HEAD 0 FFICE Rio House,/Waterside Drive, Aztec We«. Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD GAYLORD PRNTED IN USX Contents Summary.............................................................................................................................................................1 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Air Quality........................................................................................................................................... 6 3. Water Quality....................................................................................................................................... 9 4. Sewage Effluent Disposal................................................................................................................ 21 5. Industrial Discharges to Air and Water..........................................................................................25 6. Storage Use and Disposal of Radioactive Substances..................................................................28 7. Waste Management.......................................................................................................................... 30 8. Contaminated Land..........................................................................................................................36 -

Chapter 5: Vegetation of Sphagnum-Dominated Peatlands

CHAPTER 5: VEGETATION OF SPHAGNUM-DOMINATED PEATLANDS As discussed in the previous chapters, peatland ecosystems have unique chemical, physical, and biological properties that have given rise to equally unique plant communities. As indicated in Chapter 1, extensive literature exists on the classification, description, and ecology of peatland ecosystems in Europe, the northeastern United States, Canada, and the Rocky Mountains. In addition to the references cited in Chapter 1, there is some other relatively recent literature on peatlands (Verhoeven 1992; Heinselman 1963, 1970; Chadde et al., 1998). Except for efforts on the classification and ecology of peatlands in British Columbia by the National Wetlands Working Group (1988), the Burns Bog Ecosystem Review (Hebda et al. 2000), and the preliminary classification of native, low elevation, freshwater vegetation in western Washington (Kunze 1994), scant information exists on peatlands within the more temperate lowland or maritime climates of the Pacific Northwest (Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia). 5.1 Introduction There are a number of classification schemes and many different peatland types, but most use vegetation in addition to hydrology, chemistry and topological characteristics to differentiate among peatlands. The subject of this report are acidic peatlands that support acidophilic (acid-loving) and xerophytic vegetation, such as Sphagnum mosses and ericaceous shrubs. Ecosystems in Washington state appear to represent a mosaic of vegetation communities at various stages of succession and are herein referred to collectively as Sphagnum-dominated peatlands. Although there has been some recognition of the unique ecological and societal values of peatlands in Washington, a statewide classification scheme has not been formally adopted or widely recognized in the scientific community. -

Dmmo Documentary Research Checklist

Appendix 1 DMMO DOCUMENTARY RESEARCH CHECKLIST District Parish Route Crewe & Nantwich Marbury cum Quoisley FP8 Marbury cum Quoisley Wirswall FP3 Wirswall Document Date Reference Notes County Maps Burdett PP 1777 CRO PM12/16 Not shown Greenwood C 1819 CRO PM13/10 Not shown Bryant A 1831 CRO Searchroom Full length shown as ‘Lanes and Bridleways’ M.5.2 Tithe Records Marbury cum Quoisley 1838 CRO EDT/260/1 Plots 141, 145, 157, 177 and 179 list owner as Domville Halstead Cudworth Apportionment Poole; occupier of plot 141 Thomas Hale others all occupied by Domville Halstead Cudworth Poole. Marbury cum Quoisley 1838-9 CRO EDT/260/2 Route shown between two pecked lines/ one pecked line and one solid line, through plots Map 141, 145, 157, 177 and 179 Wirswall 1837 SRO P303/T/1/2 Plot 186 Dovecote field, * and Pasture 249 Public roads Apportionment Wirswall 1840 SRO P303/T/1/1 Route shown as double pecked lines, annotated ‘Bridle Road’ Map At the edge of map annotated ‘to Marbury’ Ordnance Survey Surveyors’ Drawings 1830 British Library Appears to be a route along the full length Combermere 1” First Edition 1833 PROW Unit Route shown between solid boundaries 6” First Edition 1872-5 PROW Unit Route shown as single/double pecked line, last section of southern end shown as double solid lines. 6” Second Edition As above, with the addition of B.R just to the south of Big Mere. 6” Third Edition As above, with the addition of B.R annotated on the Wirswall side of the route Appendix 1 25” County Series c. -

Antimicrobial Properties of Traditional Brewing Herbs

ANTIMICROBIAL PROPERTIES OF TRADITIONAL BREWING HERBS - Ledum palustre, Myrica gale & Humulus lupulus Gordon Virgo Project work in Ethnobiology 15 hp, 2010 Evolutionary Biology Centre (EBC) Supervisor: Hugo J. de Boer ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor Hugo de Boer for encouragement and his excellent input to this project. Thanks to Stallhagen Brewery and Marcus Lindborg for providing material and literature. Also, I would like to thank Stefan Roos at SLU and Marianne Svarvare for guidance and technique. ABSTRACT In this study, three different brewing herbs that have been used through the history are evaluated as inhibitors of common beer spoilage organisms. The three species are Ledum palustre (Marsh Tea), Myrica gale (Bog Myrtle) and Humulus lupulus (Hops). Experimental batches of 10 L were made with all the three herbs and one without any additives. For each herb, two batches were made with different concentration, one batch with 3g/L and the other with 6g/L. All batches were treated the same and fermentation pattern for all of them were similar. Inoculations of four common beer spoilage organisms were practiced in order to examine microbial resistance of the different beers. Antibacterial activity was analyzed by membrane filtration and by measure the optical density during the incubation time. Both Humulus lupulus and Myrica gale showed clear resistance to the three gram-positive bacteria. 1 INTRODUCTION Throughout history, several different plant species have been used as beer additives for flavour and above all as preservatives. Particularly two species, Myrica gale and Humulus lupulus were widely used as beer additives in Europe (Behre 1999).