Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) "Your Music Has

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pioneers of the Concept Album

Fancy Meeting You Here: Pioneers of the Concept Album Todd Decker Abstract: The introduction of the long-playing record in 1948 was the most aesthetically signi½cant tech- nological change in the century of the recorded music disc. The new format challenged record producers and recording artists of the 1950s to group sets of songs into marketable wholes and led to a ½rst generation of concept albums that predate more celebrated examples by rock bands from the 1960s. Two strategies used to unify concept albums in the 1950s stand out. The ½rst brought together performers unlikely to col- laborate in the world of live music making. The second strategy featured well-known singers in song- writer- or performer-centered albums of songs from the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s recorded in contemporary musical styles. Recording artists discussed include Fred Astaire, Ella Fitzgerald, and Rosemary Clooney, among others. After setting the speed dial to 33 1/3, many Amer- icans christened their multiple-speed phonographs with the original cast album of Rodgers and Hammer - stein’s South Paci½c (1949) in the new long-playing record (lp) format. The South Paci½c cast album begins in dramatic fashion with the jagged leaps of the show tune “Bali Hai” arranged for the show’s large pit orchestra: suitable fanfare for the revolu- tion in popular music that followed the wide public adoption of the lp. Reportedly selling more than one million copies, the South Paci½c lp helped launch Columbia Records’ innovative new recorded music format, which, along with its longer playing TODD DECKER is an Associate time, also delivered better sound quality than the Professor of Musicology at Wash- 78s that had been the industry standard for the pre- ington University in St. -

The Descending Diminished 7Ths in the Brass in the Intro

VCFA TALK ON ELLINGTON COMPOSITION TECHNIQUES FEB.2017 A.JAFFE 1.) Clarinet Lament [1936] (New Orleans references) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FS92-mCewJ4 (3:14) Compositional Techniques: ABC ‘dialectical’ Sonata/Allegro type of form; where C = elements of A + B combined; Diminution (the way in which the “Basin St. Blues” chord progression is presented in shorter rhythmic values each time it appears); play chord progression Quoting with a purpose (aka ‘signifying’ – see also Henry Louis Gates) 2.) Lightnin’ [1932] (‘Chorus’ form); reliance on distinctively individual voices (like “Tricky Sam” Nanton on trombone) – importance of the compositional uses of such voices who were acquired by Duke by accretion were an important element of his ‘sonic signature’ – the opposite of classical music where sonic conformity in sound is more the rule in choosing players for ensembles. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3XlcWbmQYmA (3:07) Techniques: It’s all about the minor third (see also discussion of “Tone Parallel to Harlem”) Motivic Development (in this case the minor 3rd; both harmonically and melodically pervasive) The descending diminished 7ths in the Brass in the Intro: The ascending minor third motif of the theme: The extended (“b9”) background harmony in the Saxophones, reiterating the diminished 7th chord from the introduction: Harmonic AND melodic implications of the motif Early use of the octatonic scale (implied at the modulation -- @ 2:29): Delay of resolution to the tonic chord until ms. 31 of 32 bar form (prefigures Monk, “Ask Me Now”, among others, but decades earlier). 3.) KoKo [1940]; A tour de force of motivic development, in this case rhythmic; speculated to be related to Beethoven’s 5th (Rattenbury, p. -

The Highest Note in the Century Since His Birth, Duke Ellington Has Been the Most Important Composer of Any Music, Anywhere Blumenthal, Bob

Document 1 of 1 The highest note In the century since his birth, Duke Ellington has been the most important composer of any music, anywhere Blumenthal, Bob. Boston Globe [Boston, Mass] 25 Apr 1999: 1. Abstract The late Duke Ellington, whose 100th birthday will be celebrated on Thursday, disliked the word "jazz." As he famously remarked, the only subsets of music he recognized were good and bad. Rather than stress categorical distinctions, Ellington preferred to celebrate artists and works that were, in another of his oft-quoted phrases, "beyond category." The magnitude of Ellington's legacy should be clear to all who can hear, and even to those who can only count. Just look at the numbers. From 1914, when he wrote "Soda Fountain Rag" as an aspiring pianist in his native Washington, D.C., until shortly before his death, on May 24, 1974, Ellington was responsible for nearly 2,000 documented compositions. From 1923, when he first gained employment in New York for his Washingtonians at Barron Wilkins's Harlem nightclub, he kept an orchestra together through boom andbust. The notion of writing for specific individuals as part of an ensemble reached its highest form of expression with Ellington. Rather than simply creating music for a three-piece trombone section, he crafted lines that fit the plungered growl of Joe "Tricky Sam" Nanton, the fluency of Lawrence Brown, and the warmth of Jual Tizol's valved instrument; and he applied this practice to every chair in the band. This led Ellington to collect musicians whose "tonal personality" (another favor-ite image) inspired him, ratherthan those who might simply blendinto an undifferentiated orchestral mass. -

Jazzreach Study Guide.Indd

1906 05/06 Centennial Season 2006 SchoolTime Study Guide JazzReach Hangin’ with the Giants Wednesday, January 25, 2006 at 11:00 am Zellerbach Hall Welcome January 9, 2006 Dear Educator and Students, Welcome to SchoolTime! On Wednesday, January 25, 2006 at 11:00 a.m., you will attend the SchoolTime performance of Hangin’ with the Giants by JazzReach. This study guide will help you prepare your students for their experience in the theater and give you a framework for how to integrate the performing arts into your curriculum. Targeted questions and activities will help students understand the history of jazz and will introduce them to some of the personalities who will be represented in the performance. Please feel free to copy any portion of this study guide. Study guides are also available online at http://cpinfo.berkeley.edu/information/education/study_guides.php. Your students can actively participate at the performance by: • OBSERVING how the musicians play their instruments. • LISTENING attentively to the music. • THINKING ABOUT improvisation and how the instruments relate to one another. • REFLECTING on what they have experienced at the theater after the performance. We look forward to seeing you at the theater! Sincerely, Laura Abrams Rachel Davidman Director Education Programs Administrator Education & Community Programs About Cal Performances and SchoolTime The mission of Cal Performances is to inspire, nurture and sustain a lifelong appreciation for the performing arts. Cal Performances, the performing arts presenter and producer of the University of California, Berkeley, fulfi lls this mission by presenting, producing and commissioning outstanding artists, both renowned and emerging, to serve the University and the broader public through performances and education and community programs. -

Mount Harissa Full Score

Jazz Lines Publications Presents Mount harissa From ‘IMPRESSIONS OF THE FAR EAST SUITE’ Arranged by duke ellington Prepared for Publication by Peter Jensen, Dylan Canterbury, Rob DuBoff, and Jeffrey Sultanof full score jlp-7405 By Duke Ellington Copyright © 1967 (Renewed) by Tempo Music, Inc., Music Sales Corporation All Rights for Tempo Music, Inc. administered by Music Sales Corporation (ASCAP) International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission. Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2015 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA duke ellington/billy strayhorn series mount harissa [from impressions of the far east suite] (1964) Biographies: Duke Ellington influenced millions of people both around the world and at home. In his fifty-year career, he played over 20,000 performances in Europe, Latin America, and the Middle East as well as Asia. Simply put, Ellington transcends boundaries and fills the world with a treasure trove of music that renews itself through every generation of fans and music-lovers. His legacy continues to live onward and will endure for generations to come. Wynton Marsalis said it best when he said, “His music sounds like America.” Because of the unmatched artistic heights to which he soared, no one deserves the phrase “beyond category” more than Ellington, for it aptly describes his life as well. When asked what inspired him to write, Ellington replied, “My men and my race are the inspiration of my work. -

Jazz at the Crossroads)

MUSIC 127A: 1959 (Jazz at the Crossroads) Professor Anthony Davis Rather than present a chronological account of the development of Jazz, this course will focus on the year 1959 in Jazz, a year of profound change in the music and in our society. In 1959, Jazz is at a crossroads with musicians searching for new directions after the innovations of the late 1940s’ Bebop. Musical figures such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane begin to forge a new direction in music building on their previous success earlier in the fifties. The recording Kind of Blue debuts in 1959 documenting the work of Miles Davis’ legendary sextet with John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley, Bill Evans, Paul Chambers and Jimmy Cobb and reflects a new direction in the music with the introduction of a modal approach to composition and improvisation. John Coltrane records Giant Steps the culmination of the harmonic intricacies of Bebop and at the same time the beginning of something new. Ornette Coleman arrives in New York and records The Shape of Jazz to Come, an LP that presents a radical departure from the orthodoxies of Be-Bop. Dave Brubeck records Time Out, a record featuring a new approach to rhythmic structure in the music. Charles Mingus records Mingus Ah Um, establishing Mingus as a pre-eminent composer in Jazz. Bill Evans forms his trio with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian transforming the interaction and function of the rhythm section. The quiet revolution in music reflects a world that is profoundly changed. The movement for Civil Rights has begun. The Birmingham boycott and the Supreme Court decision Brown vs. -

Duke Ellington 4 Meet the Ellingtonians 9 Additional Resources 15

ellington 101 a beginner’s guide Vital Statistics • One of the greatest composers of the 20th century • Composed nearly 2,000 works, including three-minute instrumental pieces, popular songs, large-scale suites, sacred music, film scores, and a nearly finished opera • Developed an extraordinary group of musicians, many of whom stayed with him for over 50 years • Played more than 20,000 performances over the course of his career • Influenced generations of pianists with his distinctive style and beautiful sound • Embraced the range of American music like no one else • Extended the scope and sound of jazz • Spread the language of jazz around the world ellington 101 a beginner’s guide Table of Contents A Brief Biography of Duke Ellington 4 Meet the Ellingtonians 9 Additional Resources 15 Duke’s artistic development and sustained achievement were among the most spectacular in the history of music. His was a distinctly democratic vision of music in which musicians developed their unique styles by selflessly contributing to the whole band’s sound . Few other artists of the last 100 years have been more successful at capturing humanity’s triumphs and tribulations in their work than this composer, bandleader, and pianist. He codified the sound of America in the 20th century. Wynton Marsalis Artistic Director, Jazz at Lincoln Center Ellington, 1934 I wrote “Black and Tan Fantasy” in a taxi coming down through Central Park on my way to a recording studio. I wrote “Mood Indigo” in 15 minutes. I wrote “Solitude” in 20 minutes in Chicago, standing up against a glass enclosure, waiting for another band to finish recording. -

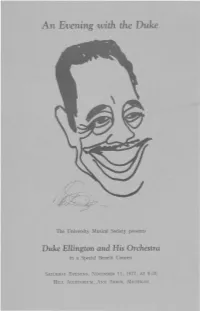

An Evening with the Duke

An Evening with the Duke The University Musical Society presents Duke Ellington and His Orchestra in a Special Benefit Concert SATURDAY EVENING, NOVEMBER 11, 1972, AT 8:30 HILL AUDITORIUM, ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN Mood Illdigo Mood ltldigo Sophisticatfd Lady Sophisticated Lady Solitllde Solitude I Lei A SOllg Go I Let A Song Go Out of My Hearl Out of My Heart DOIl't Get Around Don't Get Aroulld Milch A Ilymore Much Altymore I Got It Bad I Got It Bad Do N otMltg Til l'au Do Nothing Til You Hear From Me Hear From Me I'm Beginllillg to I'm Begilm ing to See Ihe Ligltt See the Light I'm Just A Lucky The Ann Arbor and University community I'm Just A Lucky So-alld-So welcomes Duke Ellington and his colleagues. So-and-So Just Squeeze Me Just Squeeze Me Satill Doll Their cooperation in making this evening pos Satin Doll Blac k alld Tall sible for the benefit of the University Musical Black ana Tall Fantasy Fantasy Creole Love Call Society is deeply appreciated. Creole Love Call The Mooche The Mooche Rockill' ill Rhythm Rockill' in Rhythm Warm Valley Warm Valley C Jam Bllles C Jam Blues III a Mellotone 111 a Mellotone Happy-Go-Lucky Happy-Go-Lucky Local Special Benefit Committee Local Afro-Bossa Afro-Bossa Black, Browll and Black, Brown alld Beige Sarah G. Power, Chairman Beige The Liberiall Suite Mary S. Palmer, Hazen J. Schumacher, Jr., The Liberian Suite The Perfume Suite The Perfume Suite Deep SOltth Suite Lois U. -

What the Reviews and Reviewers Are Saying About Such Sweet Thunder: Views on Black American Music

What the reviews and reviewers are saying about Such Sweet Thunder: Views on Black American Music “I truly enjoyed reading [Such Sweet Thunder] and was enthralled with its scope and depth. What is more impressive, unlike many book publications on black music and musicians, is the inclusion of noted artists and their perspectives along with scholars of certain areas of black music. Knowing how difficult photographs are hard to come by, the black and white photos vividly captured each high moment and powerful persona of each participant-artist over the twenty-five year span of the conference. Moreover, I am seriously thinking about including it as a primary reader for my survey classes in African American music. As such, I would highly recommend Such Sweet Thunder to anyone who wishes to grasp the true meaning and significance of black music in America and beyond.” Dr. Cheryl L. Keyes (Associate Professor of Ethnomusicology, University of California, Los Angeles) “In explaining why I think Such Sweet Thunder is an essential exposition of the evolution of black American music, I realized my role in the on-going sequences in the history of black American music. In reflecting on my role, my first recollection goes back to 1950, in Detroit, Michigan when I was a member of Mack McCrayry’s house band at Sonny Wilson’s Forest Club. For two weeks of that year in January the band accompanied the renowned blues singer/guitarist T. Bone Walker, who brought with him his protégé – Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown. Being a participant observer of their musical creativity during those two weeks left lasting impressions on me. -

Guide to the Felix Grant Collection

Guide to the Felix Grant Collection NMAH.AC.0410 Ben Nicastro and Scott Schwartz 1996 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Felix Grant Collection, [sound recordings] NMAH.AC.0410 Collection Overview Repository: Archives Center, National Museum of American History Title: Felix Grant Collection, [sound recordings] Identifier: NMAH.AC.0410 Date: 1935-1985 Creator: Grant, Felix, 1918-1993 Ellington, Duke, 1899-1974 Extent: 4.3 Cubic feet (6 boxes) Language: English . Summary: Collection consists of 128 albums featuring -

Dems Bulletin Duke Ellington Music Society

THE INTERNATIONAL DEMS BULLETIN DUKE ELLINGTON MUSIC SOCIETY FOUNDER: BENNY AASLAND HONORARY MEMBER: FATHER JOHN GARCIA GENSEL EDITOR: SJEF HOEFSMIT ASSISTED BY: ROGER BOYES Voort 18b, Meerle, Belgium Telephone: +32 3 315 75 83 Email: [email protected] If you are like me, you save your DEMS Bulletins and consult them with reasonable frequency. I often have trouble remembering when something was published in DEMS, thus I thought to make this Table of Contents for the DEMS Bulletins (with Sjef Hoefsmit's permission, of course). The items below are listed in the order that they were published in DEMS. Issues are arranged in reverse chronological order. Each item consists of the DEMS issue and the title and page number of each article. You can search the article titles using the search function on your internet brower, which in Netscape is Ctrl + F (both keys at the same time). Thus, if you remember reading about a good place to buy discographies somewhere in a DEMS Bulletin, hit Ctrl + F, type discog into the search window (you don't have to type the whole word) and hit enter. You will be taken to the following entry: 2001/3 DEMS 4 : Discographies available from Arthur Newman Here you learn that Arthur Newman is the man and that the information you seek is in the 2001 DEMS Bulletin, issue number 3, on page 4. Admittedly you can only find entries if you remember a word from the title of the DEMS article, but I still found this useful. I began with the most current DEMS Bulletin and am working backwards. -

The Cambridge Companion to Duke Ellington Edited by Edward Green Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88119-7 - The Cambridge Companion to Duke Ellington Edited by Edward Green Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Companion to Duke Ellington Duke Ellington is widely held to be the greatest jazz composer and one of the most significant cultural icons of the twentieth century. This comprehensive and accessible Companion is the first collection of essays to survey, in-depth, Ellington’s career, music, and place in popular culture. An international cast of authors includes renowned scholars, critics, composers, and jazz musicians. Organized in three parts, the Companion first sets Ellington’s life and work in context, providing new information about his formative years, method of composing, interactions with other musicians, and activities abroad; its second part gives a complete artistic biography of Ellington; and the final section is a series of specific musical studies, including chapters on Ellington and songwriting, the jazz piano, descriptive music, and the blues. Featuring a chronology of the composer’s life and major recordings, this book is essential reading for anyone with an interest in Ellington’s enduring artistic legacy. edward green is a professor at Manhattan School of Music, where since 1984 he has taught jazz, music history, composition, and ethnomusicology. He is also on the faculty of the Aesthetic Realism Foundation, and studied with the renowned philosopher Eli Siegel, the founder of Aesthetic Realism. Dr. Green serves on the editorial boards of The International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music, Haydn (the journal of the Haydn Society of North America), and Проблемы Музыкальной Науки (Music Scholarship), which is published by a consortium of major Russian conservatories, and is editor of China and the West: The Birth of a New Music (2009).