Grounding Sectarianism: the End of Syncretic Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dilemma of Kalabagh Dam and Pakistan Future

2917 Muhammad Iqbal et al./ Elixir Bio. Diver. 35 (2011) 2917-2920 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Bio Diversity Elixir Bio. Diver. 35 (2011) 2917-2920 Dilemma of kalabagh dam and Pakistan future Muhammad Iqbal 1 and Khalid Zaman 2 1Department of Development Studies, Comsats Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad, Pakistan. 2Department of Management Sciences, Comsats Institute of Information Technology, Abbottabad, Pakistan. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The purpose of this study is to explore the importance of Kalabagh dam in the perspective of Received: 11 April 2011; Pakistan. In addition, the study observes different views of the residents which cover all four Received in revised form: provinces of Pakistan namely, Sindh, Punjab, Khyber PukhtoonKhawa (KPK) and 20 May 2011; Baluchistan. The importance of Kalabagh dam in Pakistan is related with electricity Accepted: 27 May 2011; generation capacity which will meet the country’s power requirement. There has some reservation regarding construction of the dam. Sindh province objects that their share of the Keywords Indus water will be curtailed as water from the Kalabagh will go to irrigate farmlands in Kalabagh dam, Punjab and Khyber PukhtoonKhawa at their cost. KPK province of Pakistan has concerns Electricity generation, that large areas of Nowshera (district of KPK) would be submerged by the dam and even Power requirement, wider areas would suffer from water-logging and salinity. Further, as the water will be Pros and Cons, stored in Kalabagh dam as proposed Government of Pakistan, it will give water level rise to Pakistan. the city that is about 200 km away from the proposed location. -

Solanum Nigrum

Sci.Int.(Lahore),28(6),5251-5255,2016 ISSN 1013-5316;CODEN: SINTE 8 5251 SPATIAL VARIATIONS IN NUTRITIONAL AND ELEMENTAL PROFILE OF MAKO (Solanum nigrum) COLLECTED FROM DIFFERENT TEHSILS OF DISTRICT MIANWALI, PUNJAB, PAKISTAN Abdul Ghani1, Muhammad Nadeem2, Muhammad Mehrban Ahmed3, Mujahid Hussain4, Muhammad Ikram5 and Muhammad Imran6 1,3,4,5,6 Department of Botany, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, Punjab, Pakistan 2 Institute of Food Science and Nutrition, University of Sargodha, Sargodha, Pakistan Corresponding Author: [email protected] Key words: Spatial variation, Nutritional composition, Elemental profile, Solanum nigrum, District Mianwali ABSTRACT: The survey was conducted to assess the nutritional composition and elemental profile of Solanum nigrum collected from different tehsils (Mianwali, Esakhel, Piplan) of District Mianwali. Highest moisture (28.48%), ash (21.68%) and fat contents (14.23%) were present in tehsil Mianwali. Highest carbohydrate content (25.75%), crude fiber (13.04%) and crude protein content (0.41%) was observed in tehsil Piplan. Highest concentration of Cr (0.16mg/kg), Mg (6.76mg/kg), Mn (0.12mg/kg), Fe (8.19 mg/kg) and Pb (1.85 mg/kg) was present in tehsil Piplan. Highest concentration of Zn (3.52mg/kg) was noted in tehsil Esakhel. Highest concentration of Cd (0.82mg/kg) and Cr (0.25mg/kg) was present in samples collected from tehsil Mianwali. Variation in nutritional composition and elemental profile of Solanum nigrum may be attributed to soil composition (nutrients) and difference of climatic factor prevailing in different tehsils of District Mianwali. INTRODUCTION effective efficiency of curing diseases with no side effects The main aim of the study is to explore the nutrition and the [4]. -

Checklist of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali-Pakistan

Ethnobotanical Leaflets 10: 41-48. 2006. Check List of Medicinal Flora of Tehsil Isakhel, District Mianwali-Pakistan Mushtaq Ahmad, Mir Ajab Khan, Shabana Manzoor, Muhammad Zafar And Shazia Sultana Department of Biological Sciences, Quaid-I-Azam University Islamabad-Pakistan Issued 15 February 2006 ABSTRACT The research work was conducted in the selected areas of Isakhel, Mianwali. The study was focused for documentation of traditional knowledge of local people about use of native medicinal plants as ethnomedicines. The method followed for documentation of indigenous knowledge was based on questionnaire. The interviews were held in local community, to investigate local people and knowledgeable persons, who are the main user of medicinal plants. The ethnomedicinal data on 55 plant species belonging to 52 genera of 30 families were recorded during field trips from six remote villages of the area. The check list and ethnomedicinal inventory was developed alphabetically by botanical name, followed by local name, family, part used and ethnomedicinal uses. Plant specimens were collected, identified, preserved, mounted and voucher was deposited in the Department of Botany, University of Arid Agriculture Rawalpindi, for future references. Key words: Checklist, medicinal flora and Mianwali-Pakistan. INTRODUCTION District Mianwali derives its name from a local Saint, Mian Ali who had a small hamlet in the 16th century which came to be called Mianwali after his name (on the eastern bank of Indus). The area was a part of Bannu district. The district lies between the 32-10º to 33-15º, north latitudes and 71-08º to 71-57º east longitudes. The district is bounded on the north by district of NWFP and Attock district of Punjab, on the east by Kohat districts, on the south by Bhakkar district of Punjab and on the west by Lakki, Karak and Dera Ismail Khan District of NWFP again. -

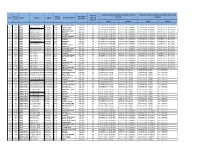

Aaaaaaaaaaaaa Type of Branch S No Branch Code Cluster

Sameday Centralized and Decentralised branches for Local Centralized and Decentralised branches for Intercity Branch Type of NIFT / NON- S No Cluster District Region Name Of Branch Clearing Clearing Clearing Code Branch NIFT AREA Branches Inward Outward Inward Outward a a a a a a a a a a a a a 1 0387 NORTH HARIPUR DISTRICT ISLAMABAD RETAIL MAIN BAZAR BRANCH NIFT AREA NO Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) 2 0465 NORTH HARIPUR DISTRICT ISLAMABAD RETAIL VILLAGE HATTAR NIFT AREA NO Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) 3 0252 NORTH ABBOTTABAD DISTRICT ISLAMABAD RETAIL PINE VIEW ROAD NIFT AREA NO Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) 4 0235 NORTH HARIPUR DISTRICT ISLAMABAD RETAIL AKBAR PLAZA (SABZI NIFT AREA NO Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) 5 0571 NORTH HARIPUR DISTRICT ISLAMABAD RETAIL HAVELIAN NIFT AREA NO Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) 6 0990 NORTH ABBOTTABAD DISTRICT ISLAMABAD RETAIL MANSEHRA NIFT AREA NO Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) Centralized (CPU - ISLAMABAD) 7 0203 NORTH HARIPUR DISTRICT ISLAMABAD RETAIL KHALABAT TOWNSHIP NIFT AREA NO Centralized (CPU -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

List of Canidates for Recuritment of Mali at Police College Sihala

LIST OF CANIDATES FOR RECURITMENT OF MALI AT POLICE COLLEGE SIHALA not Sr. No Sr. Name Address CNIC No CNIC age on07-04-21age Remarks Attached Qulification Date ofBirth Date Father Name Father Appliedin Quota AppliedPost forthe Date ofTestPractical Date Home District-DomicileHome Affidavit attached / Not Not Affidavit/ attached Day Month Year Experienceor Certificate attached 1 Ghanzafar Abbas Khadim Hussain Chak Rohacre Teshil & Dist. Muzaffargarh Mali Open M. 32304-7071542-9 Middle 01-01-86 7 4 35 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 W. No. 2 Mohallah Churakil Wala Mouza 2 Mohroz Khan Javaid iqbal Pirhar Sharqi Tehsil Kot Abddu Dist. Mali Open M. 32303-8012130-5 Middle 12-09-92 26 7 28 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Muzaffargarh Ghulam Rasool Ward No. 14 F Mohallah Canal Colony 3 Muhammad Waseem Mali Open M. 32303-6730051-9 Matric 01-12-96 7 5 24 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Khan Tehsil Kot Addu Dist. Muzaffargrah Muhammad Kamran Usman Koryia P-O Khas Tehsil & Dist. 4 Rasheed Ahmad Mali Open M. 32304-0582657-7 F.A 01-08-95 7 9 25 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Rasheed Muzaffargrah Muhammad Imran Mouza Gul Qam Nashtoi Tehsil &Dist. 5 Ghulam Sarwar Mali Open M. 32304-1221941-3 Middle 12-04-88 26 0 33 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Sarwar Muzaffargrah Nohinwali, PO Sharif Chajra, Tehsil 7 6 Mujahid Abbas Abid Hussain Mali Open M. 32304-8508933-9 Matric 02-03-91 6 2 30 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 District Muzaffargarh. Hafiz Ali Chah Suerywala Pittal kot adu, Tehsil & 7 Muhammad Akram Mali Disable 32303-2255820-5 Middle 01-01-82 7 4 39 Muzaffargarh x x 20-05-21 Mumammad District Muzaffargarh. -

49372-002: Greater Thal Canal Irrigation Project

Environmental Impact Assessment Project number: 49372–002 February 2020 PAK: Greater Thal Canal Irrigation Project Main Report Prepared by Irrigation Department, Government of the Punjab for the Asian Development Bank. This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. IRRIGATION DEPARTMENT Greater Thal Canal Irrigation Project ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Draft EIA Report January 2020 Greater Thal Canal Irrigation Project Abbreviations EIA Report CONTENTS Page No. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IX CHAPTER-1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND ....................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 PROJECT OBJECTIVE ................................................................................................................ 1-2 1.3 NATURE AND SIZE OF THE PROJECT ...................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 NECESSITY OF THE EIA ............................................................................................................ -

Annual Policing Plan for the Year 2018-19 District Mianwali

ANNUAL POLICING PLAN FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 DISTRICT MIANWALI District Police Officer, Mianwali. FOREWORD District Police cannot achieve peace and maintenance of law & order without proper planning. Police order-2002 has made it incumbent upon every District Police Officer to prepare policing plan in consultation with the District Nazim and same may be got approved from the District Public Safety Commission, (DPSC), but now, Nazim and DPSC are not functioning. The District Police Mianwali has prepared the Policing Plan of District Mianwali for the year 2018-19. This plan contains analysis of crime committed during the year 2017 & 2018, resources available during the year 2017-2018 alongwith requirement. This policing plan also indicates targets to be achieved during the year 2018-2019 alongwith mechanism to achieve these targets. The total crime in the preceding couple of the years in the district remained under control. The performance of Mianwali Police in terms of providing security to the Moharram processions, prevention of terrorism, arrest of terrorists and other Law & Order situations during the preceding year remained satisfactory. More efforts will be made in the next year to improve the performance of District Police in all sphere of police working. (MUMTAZ AHMAD DEV)PSP District Police Officer, Mianwali INTRODUCTION According to Article 32 (4) of Police Orders 2002, it is incumbent upon head of District Police to prepare Policing Plan consistent with provincial plan. The police plan shall include. a) Objectives of policing. b) Financial recourses likely to be available during the year. c) Target and mechanism to achieve them. 1.1 Our Policing pledge. -

Climate Change, Resilience, and Population Dynamics in Pakistan: a Case Study of the 2010 Floods in Mianwali District

Population Council Knowledge Commons Poverty, Gender, and Youth Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 2018 Climate change, resilience, and population dynamics in Pakistan: A case study of the 2010 floods in Mianwali District Zeba Sathar Population Council Muhammad Khalil Population Council Sabahat Hussain Population Council Maqsood Sadiq Population Council Kiren Khan Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, Environmental Public Health Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Place and Environment Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Sathar, Zeba, Muhammad Khalil, Sabahat Hussain, Maqsood Sadiq, and Kiren Khan. 2018. "Climate change, resilience, and population dynamics in Pakistan: A case study of the 2010 floods in Mianwali District." Islamabad: Population Council. This Brief is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. RESEARCH TO FILL CRITICAL EVIDENCE GAPS CLIMATE CHANGE, RESILIENCE, AND POPULATION DYNAMICS IN PAKISTAN A CASE STUDY OF THE 2010 FLOODS IN MIANWALI DISTRICT The Population Council is prioritizing research to strengthen the evidence on resilience among those who are vulnerable to environmental stressors. This research is designed to fill evidence gaps and generate the evidence decision-makers need to develop and implement effective programs and policies. popcouncil.org/research/climate-change-vulnerability- and-resilience For information on partnership and funding opportunities, contact: Jessie Pinchoff, [email protected] Suggested citation: Sathar, Zeba, A., Muhammad Khalil, Sabahat Hussain, Maqsood Sadiq, and Kiren Khan. 2018. “Climate Change, Resilience, and Population Dynamics in Pakistan: A Case Study of the 2010 Floods in Mianwali District.” Pakistan: Population Council. -

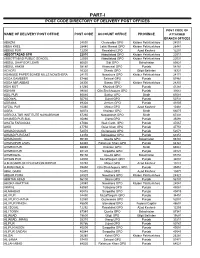

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

Ethnobotanical Studies of Plants of Mianwali District Punjab, Pakistan

Pak. J. Bot., 39(7): 2285-2290, 2007. ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDIES OF PLANTS OF MIANWALI DISTRICT PUNJAB, PAKISTAN RIZWANA ALEEM QURESHI, SYED ANEEL GILANI* AND M. ASAD GHUFRAN Department of Plant Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan *Pakistan Museum of Natural History Shakarparian, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract Medicinally important plants are necessary for the production of the various drugs and curing diseases. The local people use 26 species of the vascular plants of the Mianwali district for medicine, furniture and agricultural implements and as the food. The local community is extremely knowledgeable about the local plants but unfortunately this knowledge is going to be lost as traditional culture is disappearing. The information obtained while studying the flora of Mianwali District, Punjab is presented here. For each plant its botanical name, family name, vernacular names and method of using this plant is given. Total of 21 species belonging to 16 families were recorded for the medicinal use and five species utilized for agricultural implements and for other purposes. Introduction Mianwali is situated in the south-western part of the Punjab province. It represents the plains of the western part of the salt-ranges near the Sakesar hill (Iftikhar, 1964). It has boundaries with Bhakkar, Khushab, D.I Khan and Bannu districts. It is included in the Sargodha Division. It′s population is more than one million. About 79.22% people live in the rural area while 20.78% of people live in the urban areas (Census, 1998). Literacy rate of the city is as low as 25%. Average maximum temperature per annum is 47°C and minimum temperature is 19°C. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of District Government Mianwali

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DISTRICT GOVERNMENT MIANWALI AUDIT YEAR 2015-16 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS & ACRONYMS ....................................................... i PREFACE .................................................................................................. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................... iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ................................................. vii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics .................................................... vii Table 2: Audit observation regarding Financial Management .... vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ........................................................ vii Table 4: Irregularities Pointed Out ............................................. viii Table 5: Cost-Benefit ................................................................. viii CHAPTER-1 .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 District Government Mianwali................................................ 1 1.1.1 Introduction of Departments ................................................... 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) ...... 1 1.1.3 Brief Comments on the Status of MFDAC Audit Paras of Audit Report 2015-16.............................................................. 3 1.1.4 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance with PAC Directives ................................................................................ 3 1.2