Seeing and Being in Buddhism and Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve Mcqueen”, the New Journal and Guide, February 03, 2014

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve McQueen”, The new journal and guide, February 03, 2014 Artist and filmmaker Steven Rodney McQueen was born in London on October 9, 1969. His critically-acclaimed directorial debut, Hunger, won the Camera d’Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival. He followed that up with the incendiary offering Shame, a well- received, thought-provoking drama about addiction and secrecy in the modern world. In 1996, McQueen was the recipient of an ICA Futures Award. A couple of years later, he won a DAAD artist’s scholarship to Berlin. Besides exhibiting at the ICA and at the Kunsthalle in Zürich, he also won the coveted Turner Prize. He has exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Documenta, and at the 53rd Venice Biennale as a representative of Great Britain. His artwork can be found in museum collections around the world like the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Centre Pompidou. In 2003, he was appointed Official War Artist for the Iraq War by the Imperial War Museum and he subsequently produced the poignant and controversial project Queen and Country commemorating the deaths of British soldiers who perished in the conflict by presenting their portraits as a sheet of stamps. Steve and his wife, cultural critic Bianca Stigter, live and work in Amsterdam which is where they are raising their son, Dexter, and daughter, Alex. Here, he talks about his latest film, 12 Years a Slave, which has been nominated for 9 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. -

Sep-Oct 2019

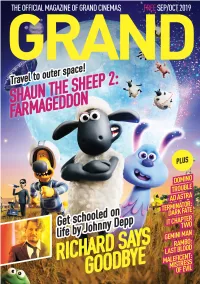

GOGRAND #alwaysentertaining SOCIALISE TALK MOVIES CL @GCLEBANON BOOK E/TICKET • E/KIOSK • GC MOBILE APP EXPERIENCE FIRSTWORD FEAT. DOLBY ATMOS ISSUE 125 When it’s time to GRAND MAGAZINE online edition kick back and relax now interactive! With school back in session, it’s easy to get caught up in preparations and never-ending homework — that’s why it’s important to unwind LOCATIONS and recharge with a dose of entertainment. And at Grand Cinemas, you can count on it. Stay tuned to our social media pages to find out LEBANON JORDAN about upcoming events, and take advantage of the G-POINTS Loyalty GRAND CINEMAS GRAND CINEMAS Card to access special offers and earn fantastic rewards. This issue in ABC VERDUN CITY MALL 01 795 697 962 65 813 461 GRAND MOMENTS, find out about the spectacular premiere attended MX4D featuring IMAX DOLBY ATMOS by French movie star Josephine Japy, among many other surprises. GRAND CLASS In our SPOTLIGHT feature, we talk to Johnny Depp about his CLUB SEATS KUWAIT GRAND AL HAMRA comedy drama Richard Says Goodbye, while 5 HOT FACTS rounds up GRAND CINEMAS LUXURY CENTER , ABC ACHRAFIEH 965 222 70 334 the most exciting tidbits about Domino starring Nikolaj Coster-Waldau. 01 209 109 MX4D ATMOS With FAMILY FIESTA you’re all set for the perfect outing: discover 70 415 200 GRAND GATE seven amazing stats about Shaun the Sheep: Farmageddon, get ready GRAND CINEMAS MALL ABC DBAYEH 965 220 56 464 to party with Big Sean and Snoop Dogg in Trouble, and check out 04 444 650 Angelina Jolie’s comeback in Maleficent: Mistress of Evil. -

Proclamation of Domination

FRIDAY January 4, 2019 BARTOW COUNTY’S ONLY DAILY NEWSPAPER 75 CENTS Better Self 101 to prepare attendees for final arrangements BY MARIE NESMITH insurance, what to [choose], who doesn’t let’s bring it to the community for free to likely happen to all of us. I believe that empowered and equip them with the [email protected] have it, etc.?’ Having buried my mother clear any cobwebs and answer any ques- being educated and prepared will help us knowledge needed to succeed in all facets and brother over the past year and [a] half, tions.” through the difficult times when we may in life,” Whitfield said. “No one really Striving to help others be “educated and I know that worrying about money is that Geared only to adults, Better Self 101 not be thinking clearly or not prepared. I wants to have these talks about death but prepared,” Will2Way Foundation Inc. and last burden that one should endure while will take take place from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. will be helping to develop some of the it’s inevitable.What better way than to let Cartersville resident Brad Cowart are join- trying to grieve through the process. at the Cartersville-Bartow County Cham- topics and getting speakers to discuss your loved ones know what you want, ing forces Jan. 12 to present Better Self “After I posed the question, I received ber of Commerce, 122 W. Main St. in them. what you have and talk about it now rather 101: Wills, Insurance, Estate Planning. -

Heather Mcintosh

HEATHER MCINTOSH COMPOSER FILM & VIDEO THE ART OF SELF-DEFENSE Andrew Kortschak, Walter Kortschak, Cody Ryder, End Cue Stephanie Whonsetler, prods. Riley Stearns, dir. WHAT IS DEMOCRACY Lea Marin, prod. National Film Board of Canada Astra Taylor, dir. HAL Jonathan Lynch, Brian Morrow, Christine Beebe, prods. Amy Scott, dir. 6 BALLOONS Channing Tatum, Samantha Housman, Peter Kiernan, Campfire Ross M. Dinerstein, Reid Carolin, prods. Marja Lewis Ryan, dir. WONDER VALLEY Rhianon Jones, prod. Wandering Vapor, LLC Heidi Hartwig, dir. LITTLE BITCHES Scott Aversano, Dan Carrillo Levy, Dom Genest, prods. Aversano Films Nick Kreiss, dir. TAKE ME Mark Duplass, Jay Duplass, Sev Ohanian, prods. Kidnap Solutions, LLC The Duplass Brothers, dir. AARDVARK Neal Dodson, Susan Leber, Zachary Quinto, prods. Great Point Media Brian Shoaf, dir. LIVING ROOM COFFIN Ian Michaels, Michael Sarrow, Sarah Smick, prods. Green Step Productions Michael Sarrow, dir. VALLEY OF THE MOON Harris Fishman, Patrick Mapel, prods. Patrick Mapel, dir. RADICAL GRACE Nicole Bernardi-Reis, Rebecca Parrish, prods. (documentary) Rebecca Parrish, dir. RAINBOW TIME Ian Michaels, Linas Phillips, prods. Duplass Brothers Productions Linas Phillips, dir. Z FOR ZACHARIAH Sophia Lin, Tobey Maguire, Skuli Fr. Malmquist, Lionsgate Matthew Plouffe, prods. Craig Zobel, dir. MANSON FAMILY VACATION Steve Bannatyne, Eric Blyler, J. Davis, J.M. Logan, prods. Lagolite Entertainment J. Davis, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. 818-260-8500 1 HEATHER MCINTOSH FAULTS Keith Calder, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Snoot Entertainment Jessica Wu, prods. Riley Stearns, dir. GASP Adam Laupus, prod. Annika Kurnick, dir. THE WHITE CITY Moti Adiv, Gil Kofman, prods. Tanner King Barklow, Gil Kofman, dirs. HONEYMOON Patrick Baker, prod. -

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

Cinephilia Or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Thomas Elsaesser Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment 2005 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Elsaesser, Thomas: Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment. In: Marijke de Valck, Malte Hagener (Hg.): Cinephilia. Movies, Love and Memory. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press 2005, S. 27– 43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/11988. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell 3.0 Lizenz zur Verfügung Attribution - Non Commercial 3.0 License. For more information gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment Thomas Elsaesser The Meaning and Memory of a Word It is hard to ignore that the word “cinephile” is a French coinage. Used as a noun in English, it designates someone who as easily emanates cachet as pre- tension, of the sort often associated with style items or fashion habits imported from France. As an adjective, however, “cinéphile” describes a state of mind and an emotion that, one the whole, has been seductive to a happy few while proving beneficial to film culture in general. The term “cinephilia,” finally, re- verberates with nostalgia and dedication, with longings and discrimination, and it evokes, at least to my generation, more than a passion for going to the movies, and only a little less than an entire attitude toward life. -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Full Press Release

IMTA ALUM GARRETT HEDLUND IN TRIPLE FRONTIER IMTA Press Release March 5, 2019 Triple Frontier opens in limited theatrical release Wednesday, March 6, and begins streaming on Netflix Wednesday, March 13. “Back in Minnesota, one of the only ways you could leave the farm was through sport. That’s why everybody in the Midwest—or at least where I grew up—is a triathlete. We all just wanted to get out. But for me, the way to get out was acting.” — Garrett Hedlund Triple Frontier centers on a group of former Special Forces operatives who reunite to plan a heist in a sparsely populated multi-border zone of South America. For the first time in their prestigious careers these unsung heroes undertake this dangerous mission for self instead of country. While each of them has served the U.S. in multiple operations— and been wounded as a reward—they still don't have the money to put kids in college, so a new plan dangles that money in front of their faces. But when events take an unexpected turn and threaten to spiral out of control, their skills, their loyalties and their morals are pushed to a breaking point in an epic battle for survival. IMTA alum Garrett Hedlund stars in Triple Frontier alongside Ben Affleck, Oscar Isaac, Charlie Hunnam, Adria Arjona and Pedro Pascal. The film is directed by Academy Award nominee J.C. Chandor and co-written by Chandor and Academy Award winner Mark Boal. The action feature is set to join the exclusive group of Netflix original films that get a theatrical release in select theaters before premiering on the streaming service. -

{FREE} a Life in Parts Ebook Free Download

A LIFE IN PARTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Bryan Cranston | 288 pages | 20 Oct 2016 | Orion Publishing Co | 9781409156574 | English | London, United Kingdom Book Review: Bryan Cranston's Memoir, "A Life in Parts" | Features | Roger Ebert Follow Us:. Woman who lost limbs now inspiring others wls. Looking at Goebel, you would notice a few fingers missing. On December 11, while wrapping Christmas presents, Loretta's life changed. Losing her hands was the most difficult. Mayor Lightfoot outlines budget proposal featuring property tax increase, layoffs. Officer involved in Breonna Taylor shooting speaks publicly. Mercy Hospital's slated closure among wave of medical centers vanishing from Chicago area. Stimulus talks inch ahead, but McConnell is resistant. HUD investigating complaint alleging Chicago zoning policies are racist. Parents of children separated at border can't be found. If you would rather read about a very human and caring star who is serious about his craft with nary a blemish in his past than the usual crash-and-burn tale, this is your book. Bryan Cranston's "A Life in Parts" is now available. To order your copy, click here. Now unchained from the grind of daily journalism, she is ready to view the world of movies with fresh eyes. Susan Wloszczyna October 11, Latest blog posts. Latest reviews. Looking for some great streaming picks? Check out some of the IMDb editors' favorites movies and shows to round out your Watchlist. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Keep track of everything you watch; tell your friends. Full Cast and Crew. Release Dates. Official Sites. -

Film & Literature

Name_____________________ Date__________________ Film & Literature Mr. Corbo Film & Literature “Underneath their surfaces, all movies, even the most blatantly commercial ones, contain layers of complexity and meaning that can be studied, analyzed and appreciated.” --Richard Barsam, Looking at Movies Curriculum Outline Form and Function: To equip students, by raising their awareness of the development and complexities of the cinema, to read and write about films as trained and informed viewers. From this base, students can progress to a deeper understanding of film and the proper in-depth study of cinema. By the end of this course, you will have a deeper sense of the major components of film form and function and also an understanding of the “language” of film. You will write essays which will discuss and analyze several of the films we will study using accurate vocabulary and language relating to cinematic methods and techniques. Just as an author uses literary devices to convey ideas in a story or novel, filmmakers use specific techniques to present their ideas on screen in the world of the film. Tentative Film List: The Godfather (dir: Francis Ford Coppola); Rushmore (dir: Wes Anderson); Do the Right Thing (dir: Spike Lee); The Dark Knight (dir: Christopher Nolan); Psycho (dir: Alfred Hitchcock); The Graduate (dir: Mike Nichols); Office Space (dir: Mike Judge); Donnie Darko (dir: Richard Kelly); The Hurt Locker (dir: Kathryn Bigelow); The Ice Storm (dir: Ang Lee); Bicycle Thives (dir: Vittorio di Sica); On the Waterfront (dir: Elia Kazan); Traffic (dir: Steven Soderbergh); Batman (dir: Tim Burton); GoodFellas (dir: Martin Scorsese); Mean Girls (dir: Mark Waters); Pulp Fiction (dir: Quentin Tarantino); The Silence of the Lambs (dir: Jonathan Demme); The Third Man (dir: Carol Reed); The Lord of the Rings trilogy (dir: Peter Jackson); The Wizard of Oz (dir: Victor Fleming); Edward Scissorhands (dir: Tim Burton); Raiders of the Lost Ark (dir: Steven Spielberg); Star Wars trilogy (dirs: George Lucas, et. -

ENGL A270 | HISTORY of FILM Fall 2021 | Tuesday & Thursday, 4:55-6

ENGL A270 | HISTORY OF FILM Fall 2021 | Tuesday & Thursday, 4:55-6:10PM Bobet 216 Instructor: Mike Miley | [email protected] | 504.865.2286 Office hours: T/Th 4:15-4:45 PM, 6:15-7:15 PM and by appointment Course Description History of Film is an introduction to the rich and troubling history, impact, and legacy of the motion picture as a commercial narrative art form. The course begins with the creation of the medium in the 1890s and travels around the globe to reach our extremely uncertain and precarious present. Although the medium has developed tremendously throughout the decades due to advancements in style, technology, production, and exhibition, the course will strive to create a sense of continuity, showing how films speak to the legacy of cinema by pointing out the ways in which films influence each other and respond to films of the past. The course will pay particular attention to films and filmmakers who divert from or critique the dominant narratives and forms of film and film history to provide students with a fuller picture of cinema’s capabilities. The goal of the course is not only to educate students on the major figures and developments in cinema but also to expose them to the dynamic field they participate in as spectators and creators to give them the necessary context for a creative and compassionate life in the field. Students who successfully complete the course will be able to demonstrate their knowledge of major events, figures, and films in the history of cinema and will be comfortable with writing about film as a narrative art. -

Tron: Legacy Is Displayed During Comic-Con in San Diego on Thursday

life TUESDAY, JULY 27, 2010 [ MEDIA ] Jezebel — the Web site that roared A recent spat over a TV show’s hiring policies could lead to blog requests being taken more seriously BY SARAH HuGHes THE GUARDIAN, NEW YORK alked about on numerous blogs and Web sites, covered by the New York Times, attacked by The Daily Show and T attracting upwards of 38m global page views a month, the women’s Web site Jezebel has clearly come of age. It also needs to be noted that the site has overtaken its infamous sibling, the gossipy Gawker, in terms of notoriety after a public spat with Jon Stewart’s Daily Show. Gaby Darbyshire, Gawker Media’s chief operating officer, told the New York Observer that Jezebel “has received more complaints per year than any other [Gawker media] site,” while Gawker’s founder, Nick Denton, told the New York Times that it was no longer seen by advertisers as “a cute new entrant” on the blogging scene. The spat with The Daily Show began with a report by the site’s Irin Carmon on the program’s hiring policies, which highlighted the lack of women in senior writing or on-air positions and argued that it was “a boys’ club where women’s contributions are often ignored and dismissed”. Although The Daily Show had declined to comment for Carmon’s original piece, a visibly flustered Stewart attempted to address the issue a week later stating: “Jezebel thinks I’m a sexist prick.” In the days that followed The Daily Show released an open letter rebutting Carmon’s report titled “Dear People Who Don’t Work Here” and signed by more than 30 female employees.