Redalyc.Rejecting the Shadow: Steve Berrios, an Apache of the Skins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (Guest Post)*

“Manteca”--Dizzy Gillespie Big Band with Chano Pozo (1947) Added to the National Registry: 2004 Essay by Raul Fernandez (guest post)* Chano Pozo and Dizzy Gillespie The jazz standard “Manteca” was the product of a collaboration between Charles Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie and Cuban musician, composer and dancer Luciano (Chano) Pozo González. “Manteca” signified one of the beginning steps on the road from Afro-Cuban rhythms to Latin jazz. In the years leading up to 1940, Cuban rhythms and melodies migrated to the United States, while, simultaneously, the sounds of American jazz traveled across the Caribbean. Musicians and audiences acquainted themselves with each other’s musical idioms as they played and danced to rhumba, conga and big-band swing. Anthropologist, dancer and choreographer Katherine Dunham was instrumental in bringing several Cuban drummers who performed in authentic style with her dance troupe in New York in the mid-1940s. All this laid the groundwork for the fusion of jazz and Afro-Cuban music that was to occur in New York City in the 1940s, which brought in a completely new musical form to enthusiastic audiences of all kinds. This coming fusion was “in the air.” A brash young group of artists looking to push jazz in fresh directions began to experiment with a radical new approach. Often playing at speeds beyond the skills of most performers, the new sound, “bebop,” became the proving ground for young New York jazz musicians. One of them, “Dizzy” Gillespie, was destined to become a major force in the development of Afro-Cuban or Latin jazz. Gillespie was interested in the complex rhythms played by Cuban orchestras in New York, in particular the hot dance mixture of jazz with Afro-Cuban sounds presented in the early 1940s by Mario Bauzá and Machito’s Afrocubans Orchestra which included singer Graciela’s balmy ballads. -

“Mongo” Santamaría

ABOUT “MONGO” SANTAMARÍA The late 1940's saw the birth of Latin Jazz in New York City, performed first by its pioneers Machito, Mario Bauza, Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo. Ramón "Mongo" Santamaría Rodríguez emerged from the next wave of Latin Jazz that was led by vibraphonist Cal Tjader and timbalero Tito Puente. When Mongo finally became a bandleader himself, his impact was profound on both the Latin music world and the jazz world. His musical career was long, ushering in styles from religious Afro-Cuban drumming and charanga-jazz to pop- jazz, soul-jazz, Latin funk and eventually straight ahead Latin jazz. From Mongo’s bands emerged some young players who eventually became jazz legends, such as Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock and Hubert Laws. I had a chance to meet Mongo a few times during the years which culminated in a wonderful hangout on my radio show Jazz on the Latin Side, broadcast on KJazz 88.1 FM in Los Angeles) where he shared great stories and he also sat in with the live band that I had on the air that night. What a treat for my listeners! After his passing I felt like jazz fans were beginning to forget him. So I decided to form Mongorama in his honor and revisit his innovative charanga-jazz years of the 1960s. Mongo Santamaría was the most impactful Jazz “conguero” ever! Hopefully Mongorama will not only remind jazz fans of his greatness, but also create new fans that will explore his vast musical body of work. Viva Mongo!!!!! - Mongorama founder and bandleader José Rizo . -

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Bobby Sanabria Reflects on His New Role at WBGO, and a Life of Advocacy for Latin Jazz

Bobby Sanabria Reflects on His New Role at WBGO, And a Life of Advocacy For Latin Jazz By NATE CHINEN • 8 HOURS AGO Latin Jazz Cruise TwitterFacebookGoogle+Email Bobby Sanabria, the new host of Latin Jazz Cruise, in the studio at WBGO. NATE CHINEN / WBGO Bobby Sanabria was a teenager, growing up in the Bronx, when he placed his first call to a radio station. The station was WRVR, a beacon of jazz in the New York area at the time, and he was calling to request a song by vibraphonist Cal Tjader. “I asked for ‘Cuban Fantasy’ — the live version from an album called Concert on the Campus,” Sanabria recalls. “Willie Bobo takes an incredible timbale solo on that track. As a percussionist, that was something I knew I needed to study.” To his surprise and dismay, the DJ at the station brusquely replied that “Cuban Fantasy” was Latin music, and had no place on a jazz program. Then he hung up. Sanabria called back again, and again and again, until finally his protestations got the song played on the air. But why had it been such a struggle? “That was when I realized this branch of the music was not considered part of the mainstream by the jazz intelligentsia,” Sanabria says. “I guess you could call that my first ‘A-ha moment’ of being an advocate. I always remember that. And I always will be a champion for this art form.” Sanabria is about to bring that passion to a new platform as the incoming host of Latin Jazz Cruise, which broadcasts on Fridays from 9 to 11 p.m. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

Robert GADEN: Slim GAILLARD

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Robert GADEN: Robert Gaden -v,ldr; H.O. McFarlane, Karl Emmerling, Karl Nierenz -tp; Eduard Krause, Paul Hartmann -tb; Kurt Arlt, Joe Alex, Wolf Gradies -ts,as,bs; Hans Becker, Alex Beregowsky, Adalbert Luczkowski -v; Horst Kudritzki -p; Harold M. Kirchstein -g; Karl Grassnick -tu,b; Waldi Luczkowski - d; recorded September 1933 in Berlin 65485 ORIENT EXPRESS 2.47 EOD1717-2 Elec EG2859 Robert Gaden und sein Orchester; recorded September 16, 1933 in Berlin 108044 ORIENTEXPRESS 2.45 OD1717-2 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded December 1936 in Berlin 105298 MEIN ENTZÜCKENDES FRÄULEIN 2.21 ORA 1653-1 HMV EG3821 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded October 1938 in Berlin 106900 ICH HAB DAS GLÜCK GESEHEN 2.12 ORA3296-2 Elec EG6519 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded November 1938 in Berlin 106902 SIGNORINA 2.40 ORA3571-2 Elec EG6567 106962 SPANISCHER ZIGEUNERTANZ 2.45 ORA 3370-1 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; Refraingesang: Rudi Schuricke; recorded September 1939 in Berlin 106907 TAUSEND SCHÖNE MÄRCHEN 2.56 ORA4169-1 Elec EG7098 ------------------------------------------ Slim GAILLARD: "Swing Street" Slim Gaillard -g,vib,vo; Slam Stewart -b; Sam Allen -p; Pompey 'Guts' Dobson -d; recorded February 17, 1938 in New York 9079 FLAT FOOT FLOOGIE 2.51 22318-4 Voc 4021 Some sources say that Lionel Hampton plays vibraphone. 98874 CHINATOWN MY CHINATOWN -

Changuito, El Misterioso

Changuito, el misterioso Rafael Lam | Maqueta Sergio Berrocal Jr. En Cuba han existido, entre muchos, otros percusionistas que residieron en el exterior, muchas estrellas: Mongo Santamaría, el Patato Valdés, Orestes Vilató, Candito Camero, Walfredo de los Reyes, Carlos Vidal Bolado. Pero, en La Habana, hay que hablar de tres percusionistas de marca mayor, de grandes ligas: Chano Pozo, rey de las congas; Tata Guines, estrella de la tumbadora y José Luis Quintana “Changuito”, rey de las pailas. Changuito cumplió años el 18 de enero, no hubo fiesta grande, unas cervezas heladas (frías) y masitas de cerdo. El pailero mayor pasó la raya de los sesenta años de vida profesional. Cuando se hable de Premio Nacional de la Música, hay que recordar a los grandes. Changuito, ¿dónde comenzaste en la música? Empiezo a tocar influido por el ambiente en mi casa, mi papá era músico y ya a los cinco años yo estaba metido en la percusión, también me ayudó mucho Roberto Sánchez Calderín, formaba piquetes con mis amigos, estuve en el grupo Cabeza de Perro, y ya en 1956 responsablemente sustituía a mi padre en la orquesta del cabaret Tropicana y en la Orquesta Habana Jazz. Cuando aquello se empezaba temprano. Le hice una suplencia a mi padre en el cabaret Tropicana. ¿Después de esas experiencias qué hiciste en todos estos años, antes de 1959? Estuve trabajando con la Orquesta de Gilberto Valdés, Quinteto José Tomé, Artemisa Souvenir, Habana Rítmica 7. ¿A partir de 1959 qué haces? Comencé con el grupo Los Bucaneros que, en aquellos tiempos tenía mucha aceptación del público joven. -

Stage Door Swings Brochure

. 0 A G 6 E C R 2 G , O 1 FEATURING A H . T T D C I O I S F A N O E O A P T B R I . P P G The Palladium Big 3 Orchestra S M . N N R U O E O Featuring the combined orchestras N P L of Tito Puente, Machito and Tito Rodriguez presents Manteca - The Afro-Cuban Music of The Dizzy Gillespie Big Band FROM with special guest Candido CUBAN FIRE Brazilliance featuring TO SKETCHES Bud Shank OF SPAIN The Music of Chico O’ Farrill Big Band Directed by Arturo O’Farrill Bill Holman Band- Echoes of Aranjuez 8 3 0 Armando Peraza 0 - 8 Stan Kenton’s Cuban Fire 0 8 0 Viva Tirado- 9 e The Gerald Wilson Orchestra t A u t C i Jose Rizo’s Jazz on , t s h the Latin Side All-Stars n c I a z Francisco Aguabella e z B a Justo Almario J g n s o Shorty Rogers Big Band- e l L , e Afro-Cuban Influence 8 g 3 n Viva Zapata-The Latin Side of 0 A 8 The Lighthouse All-Stars s x o o L Jack Costanzo B . e O h Sketches of Spain . P T The classic Gil Evans-Miles Davis October 9-12, 2008 collaboration featuring Bobby Shew Hyatt Regency Newport Beach Johnny Richards’ Rites of Diablo 1107 Jamboree Road www.lajazzinstitute.org Newport Beach, CA The Estrada Brothers- Tribute to Cal Tjader about the LOS PLATINUM VIP PACKAGE! ANGELES The VIP package includes priority seats in the DATES HOW TO amphitheater and ballroom (first come, first served JAZZ FESTIVAL | October 9-12, 2008 PURCHASE TICKETS basis) plus a Wednesday Night bonus concert. -

The Singing Guitar

August 2011 | No. 112 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Mike Stern The Singing Guitar Billy Martin • JD Allen • SoLyd Records • Event Calendar Part of what has kept jazz vital over the past several decades despite its commercial decline is the constant influx of new talent and ideas. Jazz is one of the last renewable resources the country and the world has left. Each graduating class of New York@Night musicians, each child who attends an outdoor festival (what’s cuter than a toddler 4 gyrating to “Giant Steps”?), each parent who plays an album for their progeny is Interview: Billy Martin another bulwark against the prematurely-declared demise of jazz. And each generation molds the music to their own image, making it far more than just a 6 by Anders Griffen dusty museum piece. Artist Feature: JD Allen Our features this month are just three examples of dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals who have contributed a swatch to the ever-expanding quilt of jazz. by Martin Longley 7 Guitarist Mike Stern (On The Cover) has fused the innovations of his heroes Miles On The Cover: Mike Stern Davis and Jimi Hendrix. He plays at his home away from home 55Bar several by Laurel Gross times this month. Drummer Billy Martin (Interview) is best known as one-third of 9 Medeski Martin and Wood, themselves a fusion of many styles, but has also Encore: Lest We Forget: worked with many different artists and advanced the language of modern 10 percussion. He will be at the Whitney Museum four times this month as part of Dickie Landry Ray Bryant different groups, including MMW. -

Herbie Hancock 1 Jive Hoot (Bob Brookmeyer)

MUNI 20150420 – Herbie Hancock 1 Jive Hoot (Bob Brookmeyer) 4:43 From album BOB BROOKMEYER AND FRIENDS (Columbia CS 9037 / 468413) Bob Brookmeyer-vtb; Stan Getz-ts; Gary Burton-vib; Herbie Hancock-p; Ron Carter- b; Elvin Jones-dr. New York City, May 1964. Herbie Hancock: THE COMPLETE BLUE NOTE SIXTIES SESSIONS (all compositions by Herbie Hancock) Recorded at Rudy Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey (all sessions) Three Wishes 5:10 Donald Byrd-tp; Wayne Shorter-ts; Herbie Hancock-p; Butch Warren-b; Billy Higgins-dr. December 11, 1961. From album Donald Byrd: FREE FORM (Blue Note 95961) Watermelon Man 7:08 Freddie Hubbard-tp; Dexter Gordon-ts; Herbie Hancock-p; Butch Warren-b; Billy Higgins-dr. May 28, 1962. From album TAKIN’ OFF (Blue Note 84109 / 46506) Yams 7:56 Jackie McLean-as; Donald Byrd-tp; Herbie Hancock-p; Butch Warren-b; Tony Williams-dr. February 11, 1963. Jackie McLean: VERTIGO (Blue Note LT-1085) Blind Man, Blind Man 8:16 Donald Byrd-tp; Grachan Moncur III-tb; Hank Mobley-ts; Grant Green-g; Herbie Hancock-p; Chuck Israels-b; Tony Williams-dr. March 19, 1963. MY POINT OF VIEW (Blue Note 84126 / 84126-2) Mimosa 6:34 Herbie Hancock-p; Paul Chambers-b; Willie Bobo-dr, timb; Oswaldo „Chihuahua“ Martinez-bongos, finger cymbals. August 30, 1963. INVENTIONS AND DIMENSIONS (Blue Note 84147 / -2) One Finger Snap 7:16 Freddie Hubbard-co; Herbie Hancock-p; Ron Carter-b; Tony Williams-dr. June 17, 1964. EMPYREAN ISLES (Blue Note 84175 / -2) Maiden Voyage 7:55 Dolphin Dance 9:16 Freddie Hubbard-tp; George Coleman-ts; Herbie Hancock-p; Ron Carter-b; Tony Williams-dr. -

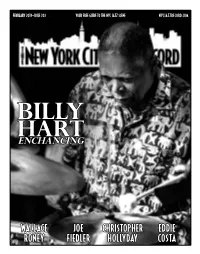

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

Leopard Society Music and Language in West Africa, Western Cuba, and New York City Ivor L

African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal Vol. 5, No. 1, January 2012, 85Á103 Bongo´ Ita´: leopard society music and language in West Africa, Western Cuba, and New York City Ivor L. Miller* Research Fellow, African Studies Center, Boston University, USA The Abakua´ mutual-aid society of Cuba, recreated from the E´ kpe` leopard society of West Africa’s Cross River basin, is a richly detailed example of African cultural transmission to the Americas. Its material culture, such as masquerades and drum construction, as well as rhythmic structures, are largely based on E´ kpe` models. Its ritual language is expressed through hundreds of chants that identify source regions and historical events; many can be interpreted by speakers of E` f`k,ı the pre-colonial lingua franca of the Cross River region (Miller 2005). With the help of both E´ kpe` and Abakua´ leaders, I have examined relationships between the musical practices of West African E´ kpe`, Cuban Abakua´, as well as Cuban migrants to the United States whose commercial recordings have evoked West African places and events historically relevant to Abakua´, meanwhile contribut- ing to the evolution of North American jazz. Keywords: Abakua´; Calabar; Cross River region; Cuba; E´ kpe` leopard society; jazz; Nigeria The E´ kpe` Imperium The leopard society of the Cross River basin is known variously as E´ kpe`, Ngbe`, and Obe`, after local terms for ‘leopard’.1 Being among the most diverse linguistic regions in the world, to simplify, I will hereafter use E´ kpe`, an E` f`kı term, the most common in the existing literature.