Land Use Controls in Historic Areas Thomas J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Council Agenda

CITY OF CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA CITY COUNCIL AGENDA Agenda Date: August 20, 2012 Action Required: Approve the 2012 Architectural Design Control (ADC) Districts Design Guidelines (5-Year Update) as recommended by the Charlottesville Board of Architectural Review (BAR) Presenter: Mary Joy Scala, Preservation & Design Planner, City of Charlottesville Staff Contacts: Jim Tolbert, Director, Neighborhood Development Services Title: 2012 Architectural Design Control (ADC) Districts Design Guidelines (5-Year Update) Background: The current ADC Districts Design Guidelines were adopted by City Council on October 17, 2005. Sec. 34-288(6) of the existing ADC District regulations requires that the Design Guidelines are updated every 5 years. On May 15, 2012 the BAR recommended (7-0) for City Council’s approval the attached revisions to the ADC Districts Design Guidelines. The Word document shows proposed deletions struck out, and proposed new text underlined, so you can see the changes. The end product will be formatted to look similar to the existing Guidelines document. Discussion: A BAR subcommittee (Fred Wolf, Eryn Brennan, Preston Coiner and Syd Knight) proposed changes that were discussed by the full BAR in November 2011. The subcommittee noted the lack of guidelines related to public landscapes, so experts Genevieve Keller, Gregg Bleam, Preston Coiner and Syd Knight were convened in December 2011 to discuss. A full BAR work session was held in January 2012 to review additional proposed guidelines for Public Landscapes and for Tents. Substantive revisions (other than typos, updates, corrections, and rearranging text) include: Chapter 5 - Signs, Awnings, Vending and Cafes (page 40) New guidelines for tents for weekend use and for winter café season or year-round use. -

9781455616602 Ch 1.Pdf

MACD Book 1.indb 14 7/9/2012 2:23:12 PM The History of Café Du Monde In May 2012, Café Du Monde celebrated its 150th anniversary. fritter, sometimes filled with fruit. Today, the beignet is a When the original location in the French Quarter opened, square piece of dough that is fried and then covered with electricity was still a decade away. Café Du Monde sits just off powdered sugar and is served in orders of three. the Mississippi River in the New Orleans French Market. The In 1942, Hubert Fernandez purchased Café Du Monde. French Market dates back to the Choctaw Indians, who used Since then, four generations of the Fernandez family have this natural Mississippi River-level location to trade their joined together to serve their guests. They have expanded to wares with travelers along the river. The French Market is nine different locations in New Orleans and the surrounding comprised of seven buildings and is anchored at the Jackson areas, while remaining family owned and operated. Square end by Café Du Monde and on the other end by the Farmers Market and flea markets. The café is located at the corner of St. Ann and Decatur in the building known as the Butcher’s Hall. This building was built in 1812, after a hurricane destroyed the original. It has undergone a number of renovations over the last two hundred years, including major changes in 1930 and 1975. Café Du Monde is world renowned for its café au lait and beignets. The signature drink is a blend of coffee and chicory, which is the root of the endive plant. -

Saint Denis in New Orleans

A SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF NEW ORLEANS & THE LOCATIONS THAT INSPIRED RED DEAD REDEMPTION 2 1140 Royal St. 403 Royal St. Master Nawak Master Nawak We start at Bastille In the mission “The Joys Next up is the Lemoyne the RDR2 storyline. Saloon, the lavish, of Civilization”, Arthur National Bank, a grand three-storied social Morgan stops here to and impressive In the mission, The Louisiana State Bank epicenter of Saint gather intel on Angelo The infamous LaLaurie representation of the “Banking, The Old serves as a real life mirror Denis, made exclusive Bronte, the notorious Mansion is a haunted largest developed city American Art”, Dutch landmark in the French to its fictitious counterpart to the upper echelons of Italian crime lord of in the country. and Hosea round up the Quarter. Madame LaLaurie in both design and purpose. gang for one last heist, society by its wealthy, Saint Denis. He is was a distinguished Creole According to Wikipedia, “the Established in 1763, a final attempt to well-to-do patrons. cautioned by the wary socialite in the early 1800’s, Louisiana State Bank was bartender to abandon later discovered to be a Saint Denis’ stateliest procure the cash they founded in 1818, and was Will you: play a dangerous waters... serial killer and building is older than need in order to start the first bank established in spirited, high-stakes slave torturer. the country itself. over as new men in a the new state of Louisiana game of poker with a This is also the only When her despicable crimes Heiresses and captains free world. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

The Cup, the Cap and the Cupola Cupolas and coppolas can both be found atop domes, and in New Orleans they can also be found in the French Quarter (in more ways than one). In architecture, a cupola is itself a dome-like ornamental structure located on top of another larger dome or roof. It can be used as a “lookout” or to admit light and ventilation. This Italian word comes from the classical Latin word for a small cup, since this mini- dome resembles an upside down cup. Cupolas can be found positioned above the Cabildo, Presbytere and the Napoleon House. The Presbytere had a cupola just like the Cabildo until the hurricane of 1915. After over ninety years without bilateral symmetry, the Presbytere is back to normal (with a design by the architectural firm of Yeates & Yeates). The Presbytere in New Orleans, with its restored cupola The Italian word coppola is the name for the traditional cloth cap that can be seen worn on men’s “domes” back in Sicily in the film classic “The Godfather”. It is so appropriate that the movie’s director and part-time Quarterite is the acclaimed director and screenwriter, Francis Ford Coppola. Another French Quarter homeowner is his nephew, actor Nicolas Cage, nee Nicholas Kim Coppola. In 2007, Cage paid $3,450,000 for the famous LaLaurie mansion at 1140 Royal Street. Delphine LaLaurie (who first lived there in 1831) was infamous for her sadistic treatment of her slaves, and it is said that the home is haunted. Another Italian word for cupola (usually if a stair is involved) is belvedere, literally meaning a “beautiful view”. -

Private Dining Guide

Private Dining Guide Thank you for considering Napoleon House for your upcoming event. Napoleon House offers a prime, historic French Quarter setting, Chef Chris Montero’s acclaimed classic New Orleans cuisine, caring service and heartfelt hospitality. Our ambition is to deliver a very special, one-of-a-kind event that will charm your guests and reflect your palate, theme and budget Constructed in the late 1700’s; owned and operated by the Impastato family of New Orleans for 101 years and Ralph Brennan since May of 2015, the Napoleon House (named for the exiled French Emperor who was offered the opportunity to take up residence) suspends you in time. It’s authentic exterior, deeply patinaed walls, heart of pine floors, sunken cypress doors, and luminous photography exudes the European charm that begets civilized eating and drinking. The upstairs private rooms boast glittering custom chandeliers, antiqued cypress wood mantles, heirloom silk tapestry drapes and balcony access with breathtaking views of the French Quarter. The Cupola at the very top of the building was long used by sailors as a premier destination to view the boating traffic along the Mississippi River, and also by the original owner, former New Orleans Mayor Nicholas Giraud who would retreat to this treasured space to wait for Napoleon Bonaparte, who sadly was poisoned before his rumored arrival. Napoleon House offers several enchanting event spaces. The upstairs Rosa and Pietro Rooms can accommodate up to 135 for receptions and 70 for seated events. Downstairs the Emperor’s Room stands 40 and seats 30. We also offer our courtyard and iconic bar area for groups of 25 and up to 75 respectively. -

Where the Locals Go

Where The Locals Go Stone Pigman's Top New Orleans Picks Where The Locals Go 1 The lawyers of Stone Pigman Walther Wittmann L.L.C. welcome you to the great city of New Orleans. Known around the world for its food, nightlife, architecture and history, it can be difficult for visitors to decide where to go and what to do. This guide provides recommendations from seasoned locals who know the ins-and-outs of the finest things the city has to offer. "Antoine’s Restaurant is the quintessential classic New Orleans restaurant. The oldest continuously operated family owned restaurant in the country. From the potatoes soufflé to the Baked Alaska with café Diablo for dessert, you are assured a memorable meal." (713 St. Louis Street, New Orleans, LA 70130 (504) 581-4422) Carmelite Bertaut "My favorite 100+ year old, traditional French Creole New Orleans restaurant is Arnaud’s. It's a jacket required restaurant, but has a causal room called the Jazz Bistro, which has the same menu, is right on Bourbon Street, and has a jazz trio playing in the corner of the room." (813 Bienville Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70112 (504) 523-5433) Scott Whittaker "The food at Atchafalaya is delicious and the brunch is my favorite in the city. The true standout of the brunch is their build-your-own bloody mary bar. It has everything you could want, but you must try the bacon." (901 Louisiana Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70115 (504) 891-9626) Maurine Wall "Chef John Besh’s restaurant August never fails to deliver a memorable fine dining experience. -

![The American Legion Magazine [Volume 74, No. 5 (May 1963)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5402/the-american-legion-magazine-volume-74-no-5-may-1963-2735402.webp)

The American Legion Magazine [Volume 74, No. 5 (May 1963)]

THE AMERICAN 20C • MAY 1963 I J m j Ji JL x^rJJ^ MAGAZINE V SEE PAGE 26 The Legion Hosts ! ENTER THE COCA-COLA BOTTLERS' 250,000 ©©i^IIIISn®^ SWEEPSTAKES! C. Dorsett 16' Runabout D. Evinrude 75 HP Starflite V Motor E. Super Gator Trailer B. 1963 Ford Country Sedan Station Wagon A. 1963 Thunderbird Convertible by Ford F. 2 Pair Cypress Gardens Water Skis G. Wenzel Camping Equipment for four H. Coleman Camping Set I. Pflueger "Freespeed" Spinning Kit J. Pflueger "Junior" Fishing Set Win all this, plus $20,000 in cash K. Spalding Sports Chest L. Kodak 8 MM Movie Outfit First Prize total value: $33,000! M. Kodak "Starmite" Camera Outfit N. $1,000 Oil Company Credit Card Sweepstakes rules - -read carefully. 2nd PRIZE: $10,000 Cash • $500 Oil Company Credit Card • PLUS: All HERE'S ALL YOU DO TO ENTER: the merchandise listed in First Prize, except the Thunderbird. 24 3rd 1. On an official entry blank, or a plain of the Sweepstakes will be final. Only one PHIZES: 1963 Ford Country Sedan Station Wagon • 2 Wenzel Sleeping piece of paper, hand print or write clearly prize to a family. No substitutions will be Bags • Coleman Camping Set • Pflueger "Freespeed" Spinning Kit • your name and address along with the made for any prize offered. All entries be- name of your favorite retail store. Mail to: come the property of The Coca-Cola Com- Pflueger "Junior" Fishing Set • Cypress Gardens Water Skis • Spalding Go America Sweepstakes, P.O. Box 468, pany and none will be returned. -

HNOC Q2 02.Pdf

THE HISTORIC THE MARY MEEKS MORRISON NEW ORLEANS AND QUARTERLY JACOB MORRISON PAPERS 1883-1998 Volume XX, Number 2 Spring 2002 Mary Morrison and Jacob Morrison (MSS 553); View down Royal Street from 100 block by Charles L. Franck, 1940 (1979.325.5516) We of New Orleans are fortunate in having with us today a link forming a continuity with the past. It is reassuring in “this day of changing concepts, of families dividing, of the tearing up of roots to be able to live beside history. It makes us proud of our heritage, it encourages us to live up to it and it bespeaks an earthly immortality in future generations. Few spots in the United States can boast these steadying influences and no place can show a complete city of them.” All quotes are from the typescript of New Orleans, Then and Now, a speech given by Mary Morrison several times during the 1970s (MSS 553). HE ARY EEKS ORRISON he early 1930s and ’40s witnessed T M M M the emergence of one of the most AND T important movements in recent New Orleans history. A dedicated group of people who recognized the singularity of JACOB MORRISON PAPERS the Vieux Carré, or French Quarter, began efforts to defend its integrity. With street 1883-1998 after street of irreplaceable historic struc- tures, the French Quarter was increasingly under threat from both the elements and Hundreds of items in the Morrison commercial developers whose plans were at Papers attest to the extraordinary tenacity of odds with maintaining the distinctive char- local preservationists to defeat the proposed acter of the neighborhood. -

Processes, Mechanisms, and Interventions WELCOME to the 2019 SOCIETY of PEDIATRIC PSYCHOLOGY ANNUAL CONFERENCE

APRIL 4-6, 2019 | NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA CELEBRATING 50 YEARS OF SPP 1969-2019 Risk and Resilience in Pediatric Psychology: Processes, Mechanisms, and Interventions WELCOME TO THE 2019 SOCIETY OF PEDIATRIC PSYCHOLOGY ANNUAL CONFERENCE e welcome you to the 2019 Society of Pediatric Psychology Annual Conference (SPPAC). Please take a few minutes to read through the program, where you will find information regarding Contents preconference workshops, plenary addresses, concurrent symposia, professional development sessions, poster W General Information ...........................3-4 presentations, and continuing education. This year we are celebrating the Society of Pediatric Psychology’s Acknowledgments .............................4-5 50th anniversary. Our conference theme is Risk and Resilience in About Our Plenary Speakers. .6 Pediatric Psychology: Processes, Mechanisms, and Interventions. Detailed Conference Program .................7-15 The conference features programming on important and timely topics relevant to preventive interventions, early identification and Thursday-at-a-Glance ............................8 intergenerational transmission of risk, health disparities, resilience Friday-at-a-Glance ..............................12 and protective factors, and the promotion of well-being for children and their families. The conference also includes programming to Saturday-at-a-Glance ............................15 meet the unique professional development needs of pediatric Continuing Education Information. 16 psychologists at all -

For Sharing... Starters Soups & Salads Sides 6.00 Featured

Strawberry Radler Blueberry Mojito FEATURED Abita Strawberry Beer, Bushmill’s Red Irish Whiskey, Cruzan Aged Silver Rum, Fresh Blueberries, Mint, LUNCH Fresh Lemon Juice & Orange Bitters 7 Lime, Soda Water 7 Pimms Cup Red Fish Mary DRINKS Pimm’s No. 1, Cucumber, Fresh Citrus, Ginger Beer 7 Housemade Bloody Mary Mix, Vodka, Seasoned Rim, Pickled Vegetables 10 FOR SHARING... HARD HAT PO-BOY LUNCH Red Fish Grill Seafood Sampler The street may be closed, but the sidewalk is open... Fried Green Tomatoes & Crawfish, Alligator Boudin Balls, and Creole Marinated Gulf Shrimp 29.95 Award-Winning Seafood Po-Boys $14.95 includes your choice of Creole potato salad or house-cut French fries BBQ Oysters - Our Signature! flash fried oysters, Crystal BBQ sauce, housemade blue cheese dressing Grilled Gulf Shrimp BBQ Oyster Po-Boy 11.95 (½ dozen) / 19.95 (dozen) / 37.95 (double dozen) & Blackened Avocado Po-Boy “Best Seafood Po-Boy” - Po-Boy Festival ‘10-’14, ‘16 “Best Shrimp Po-Boy” - Po-Boy Festival 2010 flash fried oysters tossed in Crystal Gulf Oysters on the Half-Shell* blackened avocado relish, smoked BBQ sauce, romaine lettuce, tomato, red cocktail sauce, horseradish, crackers onion mayo, romaine lettuce, tomato onion, housemade blue cheese dressing 8.95 (½ dozen) / 15.95 (dozen) / 29.95 (double dozen) Surf & Turf Po-Boy Gulf Shrimp *There may be a risk associated with consuming raw shellfish, as is the case “What the @#&$ Po-Boy” - Po-Boy Festival 2015 & Pimento Cheese Panini with other raw protein products. If you suffer from chronic illness of the liver, housemade hot sausage, “Best Shrimp Po-Boy” - Po-Boy Festival 2016 stomach, or blood or have other immune disorders, you should eat these products fully cooked. -

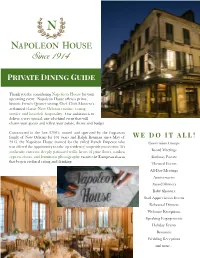

Private Dining Guide

Private Dining Guide Thank you for considering Napoleon House for your upcoming event. Napoleon House offers a prime, historic French Quarter setting, Chef Chris Montero’s acclaimed classic New Orleans cuisine, caring service and heartfelt hospitality. Our ambition is to deliver a very special, one-of-a-kind event that will charm your guests and reflect your palate, theme and budget Constructed in the late 1700’s; owned and operated by the Impastato family of New Orleans for 101 years and Ralph Brennan since May of WE DO IT ALL! 2015, the Napoleon House (named for the exiled French Emperor who Convention Groups was offered the opportunity to take up residence) suspends you in time. It’s authentic exterior, deeply patinaed walls, heart of pine floors, sunken Board Meetings cypress doors, and luminous photography exudes the European charm Birthday Parties that begets civilized eating and drinking. Themed Events All-Day Meetings Anniversaries Award Dinners Baby Showers Staff Appreciation Events Rehearsal Dinners Welcome Receptions Speaking Engagements Holiday Events Reunions Wedding Receptions and more... Rosa Room 30 SEATED / 40 RECEPTION The upstairs private rooms boast glittering custom chandeliers, antiqued cypress wood mantles, heirloom silk tapestry drapes and balcony access with breathtaking views of the French Quarter. The Cupola at the very top of the building was long used by sailors as a premier destination to view the boating traffic along the Mississippi River, and also by the original owner, former New Orleans Mayor Nicholas Giraud who would retreat to this treasured space to wait for Napoleon Bonaparte, who sadly was poisoned before his rumored arrival. -

Welcome to New Orleans “The Big Easy” Le Vieux Carré (The French

Welcome to New Orleans “The Big Easy” Prepared by Bill Paquette, Merlot History Co-Editor Introduction: Over the last ten years, I have had the pleasure to visit New Orleans for many professional conferences and conventions. During those visits I have been fortunate to tour the Vieux Carré (the French Quarter) and the Garden District to enjoy its history, jazz, and cuisine. Anne Rice no longer writes about vampires and her house in the Garden District is for sale. You will miss the pleasure of seeing her arrive in a coffin in a hearse with limos of ghouls who carried her coffin into the New Orleans bookstores for author signings. Even though Anne Rice and LeStat are gone, there is still much to see and enjoy including a waterfront casino. Here are a few suggestions given our brief time in New Orleans. Le Vieux Carré (The French Quarter) Locations: Bourbon Street: Bars and jazz clubs. Chatres Street: Elegant and funky antiques shops Royal Street: Antiques and the home to the Blue Dog paintings. Sites: Cathedral of St. Louis: The oldest Roman Catholic Church in the United States faces Jackson (General/President Andrew Jackson) Square. The Square is home to restaurants and street artists, particularly on weekends. Cabildo: 701 Chatres Street, the site of the signing of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty. Old Ursuline Convent: 1100 Chatres Street, the oldest building in the Mississippi River Valley. William Faulkner: Faulkner House Books, 624 Pirates Alley. This is where William Faulkner lived and wrote Soldier’s Pay and Mosquitoes. Truman Capote: Resided at 711 Royal Street in 1945 and wrote Other Voices, Other Rooms.