Descant 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

Issue 04 2017

The Final Frontier Podcasts Aplenty Culture Club Danielle Maynard interviews solar scientist Jordan Margetts welcomes you to Night Vale Daniel Vernon reflects on the rebirth of āM ori Lucie Green; steers clear of Star Trek references and other places representation in pop culture [1] ISSUE FOUR CONTENTS 8 10 NEWS COMMUNITY HOUSING HANG-UPS FLEEING AMERICA We’re still talking about those An American seeks sanctuary in pesky foreign investors Auckland 20 22 FEATURES LIFESTYLE A BETTER DONALD RAW Nikki Addison is madly in love Like the food at Little Bird with Donald Glover Unbakery, not like the wrestling 25 33 ARTS COLUMNS GARY OF THE PACIFIC PRESCIENT POPULAR CULTURE An interview with lead actor, Josh Thomson Michael Clark discusses finding solace in the surreal Got a legal problem e.g. Tenancy or Struggling to pay Employment? your bills? Dissatisfied with your course or grades? We can help! Have a dispute with a student or staff member? Facing a disciplinary meeting? Having a personal crisis? We offer free support, advice and information to all students. Student Advice Hub Free // Confidential // Experienced // Independent[4] Old Choral Hall (Alfred St Entrance) [email protected] 09 923 7299 www.ausa.org.nz Got a legal problem e.g. Tenancy or EDITORIAL Struggling to pay Employment? your bills? Catriona Britton Samantha Gianotti Dissatisfied with your course or grades? In Virginia, high school football is a way of life We at Craccum are very fond of finding ways to care about, or accepting free trials of things that when well-known characters are white and di- distract ourselves from the crushing weight of their followers might be interested in. -

Excesss 2017-Jan-March by Artist

Excesss 2017-Jan-March by Artist Artist Song Title Artist Song Title Adele Daydreamer Chainsmokers, The Paris Remedy Chainsmokers, The & Daya Don't Let Me Down Water Under The Bridge Chance The Rapper & 2 No Problem Alaina, Lauren Queen Of Hearts Chainz & Lil Wayne Road Less Traveled, The Charli XCX & Lil Yachty After The Afterparty Aldean, Jason Any Ol' Barstool Chesney, Kenny Bar At the End of the Little More Summertime, World A Rich & Miserable Alice in Chains Fear the Voices Childish Gambino Redbone Nutshell Christmas/Terry, Matt When Christmas Comes Amine Caroline Around Aoki, Steve & Louis Just Hold On Church, Eric Kill A Word Tomlinson Clarkson, Kelly It's Quiet Uptown Arthur, James Safe Inside Clean Bandit & Sean Paul Rockabye Say You Won't Let Go & Anne-Marie Say You Wouldn't Let Go Coldplay Everglow Ashanti Helpless Combs, Luke Hurricane B-52's, The Dance This Mess Around Cooper, JP September Song Meet The Flintstones Craig, Adam Just a Phase Badu, Erykah Back in the Day (puff) Cullum, Jamie Old Devil Moon Band Perry, The Stay in the Dark David, Craig Change My Love Beathard, Tucker Rock On Day, Andra Burn Beatles, The I Want You (She's So Rise Up Heavy) Degraw, Gavin She Sets the City On Fire Bellion, Jon All Time Low Depeche Mode Strangelove Big Sean Bounce Back Stripped Bjork Bachelorette Dirty Heads That's All I Need Joga DJ Snake & Justin Bieber Let Me Love You Play Dead Dr Dre Keep Their Heads Ringin' Blunt, James Love Me Better Drake Fake Love Bone Thugs 'n' Harmony Crossroads Dropkick Murphys I'm Shipping Up To Boston -

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 19Th December, 2016 Compiled by the Music Network© FREE SIGN UP

AUSTRALIAN SINGLES REPORT 19th December, 2016 Compiled by The Music Network© FREE SIGN UP ARTIST TOP 50 Combines airplay, downloads & streams #1 SINGLE ACROSS AUSTRALIA Starboy 1 The Weeknd | UMA starboy Rockabye The Weeknd ft. Daft Punk | UMA 2 Clean Bandit | WMA Say You Won't Let Go 3 James Arthur | SME Riding the year out at #1 on the Artist Top 50 is The Weeknd’s undeniable hit Starboy ft. Daft Punk. Black Beatles Overtaking Clean Bandit’s Rockabye ft. Sean Paul & Anne-Marie which now sits at #2, Starboy has 4 Rae Sremmurd | UMA stuck it out and finally taken the crown. Vying for #1 since the very first issue of the Australian Singles Scars to your beautiful Report and published Artist Top 50, Starboy’s peak at #1 isn’t as clear cut as previous chart toppers. 5 Alessia Cara | UMA Capsize The biggest push for Starboy has always come from Spotify. Now on its eighth week topping the 6 Frenship | SME streaming service’s Australian chart, the rest of the music platforms have finally followed suit.Starboy Don't Wanna Know 7 Maroon 5 | UMA holds its peak at #2 on the iTunes chart as well as the Hot 100. With no shared #1 across either Starvi n g platforms, it’s been given a rare opportunity to rise. 8 Hailee Steinfeld | UMA Last week’s #1, Rockabye, is still #1 on the iTunes chart and #2 on Spotify, but has dropped to #5 on after the afterparty 9 Charli XCX | WMA the Hot 100. It’s still unclear whether there will be one definitive ‘summer anthem’ that makes itself Catch 22 known over the Christmas break. -

California State University, Northridge Hidden Gifts A

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE HIDDEN GIFTS A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Screenwriting By Sean Flaherty May 2010 The thesis of Sean Flaherty is approved: Eric Edson Date Thomas McWilliams Date Date California State University, Northridge 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS SIGNATURE PAGE 11 ABSTRACT lV Hidden Gifts 1 111 ABSTRACT PREMISE FOR HIDDEN GIFTS By Sean Flaherty Master of Arts in Screenwriting Hidden Gifts is a detective thriller about Yolanda Martinez, an angry young obituary writer with deep psychological wounds, who, upon being released from a bizarre "experiment", wants to find and bring to justice the man responsible for her ordeal. Dismissed by the authorities, Yolanda has no way to pursue this end, until her former captor returns her journal of the experiment in order for her to "write her story." Yolanda, however, chooses to locate her fellow ex-captives for help in her quest, which seems increasingly impossible because they prove unable if not unwilling to provide her with assistance. Yolanda's desperation grows when she discovers not only that the experiment's mastermind is a rogue CIA agent but that his experiment with Yolanda was merely a trial run for an experiment involving the country's top political and business leaders. We will know that Yolanda has succeeded when she finally meets the CIA man again, understands him, and even tries to protect him from the authorities, just before his corrupt superior has him shot to death. lV FADE JN: MOUNTAINS. FOREST. THE WILDERNESS OF THE AMERICAN WEST. -

Sample Report Only

SAMPLE REPORT ONLY BROADCASTER COMPREHENSIVE DRT REPORT SIRIUS/XM - HITS 1 REPORT DATES FROM 2/19/2017 - 2/25/2017 ARTIST SONG TITLE LABEL AIRPLAY TIMES RUNAGROUND CHASE YOU DOWN ROBBINS 2/19/2017 0:01 ZAYN\/TAYLOR SWIFT I DON'T WANNA LIVE FOREVER 50 SHADES DARKER/RCA 2/19/2017 0:09 BRUNO MARS THAT'S WHAT I LIKE ATLANTIC 2/19/2017 0:18 TWENTY ONE PILOTS HEATHENS FUELED BY RAMEN 2/19/2017 0:26 KATY PERRY\/SKIP MARLEY CHAINED TO THE RHYTHM CAPITOL 2/19/2017 0:34 RIHANNA LOVE ON THE BRAIN ROC NATION/DEF JAM 2/19/2017 0:43 THE CHAINSMOKERS\/HALSEY CLOSER COLUMBIA 2/19/2017 0:51 BRUNO MARS 24K MAGIC ATLANTIC 2/19/2017 0:59 JULIA MICHAELS ISSUES REPUBLIC 2/19/2017 1:08 HAILEE STEINFELD\/GREY\/ZEDD STARVING UNIVERSAL REPUBLIC 2/19/2017 1:16 JON BELLION ALL TIME LOW CAPITOL 2/19/2017 1:24 ZAYN MALIK PILLOWTALK 50 SHADES DARKER/RCA 2/19/2017 1:33 TWENTY ONE PILOTS HEAVYDIRTYSOUL FUELED BY RAMEN 2/19/2017 1:41 ZAYN\/TAYLOR SWIFT I DON'T WANNA LIVE FOREVER 50 SHADES DARKER/RCA 2/19/2017 1:49 PANIC! AT THE DISCO DEATH OF A BACHELOR FUELED BY RAMEN 2/19/2017 1:57 AJR WEAK RED/SONY/BMG 2/19/2017 2:06 PANIC! AT THE DISCO L.A. DEVOTEE FUELED BY RAMEN 2/19/2017 2:14 CALUM SCOTT DANCING ON MY OWN CAPITOL 2/19/2017 2:22 CLEAN BANDIT\/SEAN PAUL\/ANNE MARIEROCKABYE ATLANTIC UK 2/19/2017 2:30 @MIKEYPIFF HIT-BOUND UNKNOWN 2/19/2017 2:38 LINKIN PARK\/KIIARA HEAVY WARNER BROTHERS 2/19/2017 2:47 LITTLE MIX TOUCH SYCO/COLUMBIA 2/19/2017 2:55 PITBULL\/FLO RIDA\/LUNCHMONEY LEWISGREEN LIGHT 305/RCA 2/19/2017 3:03 MARTIN GARRIX\/BEBE REXHA IN THE NAME OF LOVE RCA 2/19/2017 -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

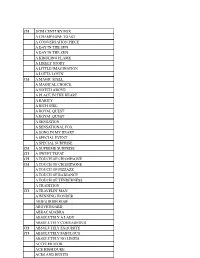

Saddlebred Sidewalk List.Docx

CH 20TH CENTURY FOX A CHAMPAGNE TOAST A CONVERSATION PIECE A DAY IN THE SUN A DAY IN THE SUN A KINDLING FLAME A LIKELY STORY A LITTLE IMAGINATION A LOTTA LOVIN' CH A MAGIC SPELL A MAGICAL CHOICE A NOTCH ABOVE A PLACE IN THE HEART A RARITY A RICH GIRL A ROYAL QUEST A ROYAL QUEST A SENSATION A SENSATIONAL FOX A SONG IN MY HEART A SPECIAL EVENT A SPECIAL SURPRISE CH A SUPREME SURPRISE CH A SWEET TREAT CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ A TOUCH OF RADIANCE A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS A TRADITION CH A TRAVELIN' MAN A WINNING WONDER ABIE'S IRISH ROSE ABOVE BOARD ABRACADABRA ABSOLUTELY A LADY ABSOLUTELY COURAGEOUS CH ABSOLUTELY EXQUISITE CH ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS ABSOLUTELY NO LIMITS ACCELERATOR ACE HIGH DUKE ACES AND EIGHTS ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS ACE HIGH DUKE ACES AND EIGHTS ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS ACE'S QUEEN ROSE ACE'S REFRESHMENT TIME ACE'S SOARING SPIRIIT ACE'S SWEET LAVENDER ACE'S TEMPTATION ACTIVE SERVICE ADF STRICTLY CLASS ADMIRAL FOX ADMIRAL'S AVENGER ADMIRAL'S BLACK FEATHER ADMIRAL'S COMMAND CH ADMIRAL'S FLEET CH ADMIRAL'S MARK CH ADMIRAL'S MARK ADMIRAL'S SHIPMATE CH ADVANTAGE ME CH ADVANTAGE ME AFFAIR OF THE HEART "JAKE" AFLAME AGLOW AGLOW AHEAD OF THE CLASS AIN'T MISBEHAVIN AIN'T MISBEHAVIN AIR OF ELEGANCE CH ALETHA STONEWALL ALEXANDER THE GREAT ALEXANDER'S EMERAUDE ALEXANDER'S EMERAUDE ALFIE ALICE LOU'S DENMARK CH ALISON MACKENZIE CH ALISON MACKENZIE CH ALL AMERICAN BOY ALL DRESSED UP ALL NIGHT LONG ALL ROSES ALL SHOW ALL THE MONEY ALLEGORY ALLIE COME LATELY "BAH" ALL'S CLEAR ALLSWEET ALLURING LADY ALONG CAME A SPIDER ALTERED IMAGE ALTON BELLE ALONG CAME A SPIDER ALTERED IMAGE ALTON BELLE CH ALVIN'S MR. -

Marychain Speed Mp3, Flac, Wma

Marychain Speed mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Speed Country: UK & Europe Released: 1993 Style: Alternative Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1137 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1217 mb WMA version RAR size: 1475 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 806 Other Formats: ASF MPC DMF RA TTA AIFF MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits 1 Snakedriver 3:39 2 Something I Can't Have 3:01 3 Write Record Release Blues 2:56 Little Red Rooster 4 3:26 Written-By – Dixon* Companies, etc. Designed At – Warsaw Phonographic Copyright (p) – Warner Music UK Ltd. Copyright (c) – Warner Music UK Ltd. Credits Engineer – Dick Meaney Producer – Jim Reid, William Reid Sleeve – Greg* Written-By – Reid* (tracks: 1 to 3), Reid* (tracks: 1 to 3) Notes Track 1 taken from the forthcoming Paramount Picture film The Crow (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack). Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 4509-93067-2 4 Matrix / Runout: 450993067-2 WME Label Code: LC 4281 Distribution Code: France WE739 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Sound Of Speed The Jesus & Blanco Y NEG66TE E.P. (10", EP, NEG66TE UK 1993 Mary Chain* Negro Ltd, Num) The Jesus And Sound Of Speed Blanco Y NEG 66C NEG 66C UK 1993 Mary Chain E.P. (Cass, EP) Negro Australia Sound Of Speed Warner Music 4509-93067-2 Marychain* 4509-93067-2 & New 1993 E.P. (CD, EP) (Australia) Zealand Blanco Y NEG 66, The Jesus & Sound Of Speed NEG 66, Negro, Blanco UK 1993 4509-93067-7 Marychain* E.P. (7", EP) 4509-93067-7 Y Negro Related Music albums to Speed by Marychain 1. -

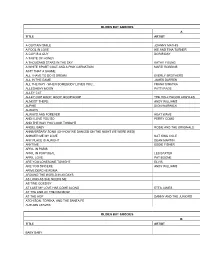

Oldies but Goodies a Title Artist a Certain Smile Johnny Mathis a Fool in Love Ike and Tina Turner a Guy Is a Guy Doris Day a Ta

OLDIES BUT GOODIES A TITLE ARTIST A CERTAIN SMILE JOHNNY MATHIS A FOOL IN LOVE IKE AND TINA TURNER A GUY IS A GUY DORIS DAY A TASTE OF HONEY A THOUSAND STARS IN THE SKY KATHY YOUNG A WHITE SPORT COAT AND A PINK CARNATION MARTI ROBBINS AIN'T THAT A SHAME ALL I HAVE TO DO IS DREAM EVERLY BROTHERS ALL IN THE GAME JAMES DARREN ALL THE WAY - WHEN SOMEBODY LOVES YOU… FRANK SINATRA ALLEGHENY MOON PATTI PAGE ALLEY CAT ALLEY OOP BOOP, BOOP, BOOP BOOP THE HOLLYWOOD ARGYLES ALMOST THERE ANDY WILLIAMS ALPHIE DION WARWICK ALWAYS ALWAYS AND FOREVER HEAT WAVE AND I LOVE YOU SO PERRY COMO AND THE WAY YOU LOOK TONIGHT ANGEL BABY ROSIE AND THE ORIGINALS ANNIVERSARY SONG (OH HOW WE DANCED ON THE NIGHT WE WERE WED) ANSWER ME MY LOVE NAT KING COLE ANY PLACE IS ALRIGHT DEAN MARTIN ANYTIME EDDIE FISHER APRIL IN PARIS APRIL IN PORTUGAL LES BAXTER APRIL LOVE PAT BOONE ARE YOU LONESOME TONIGHT ELVIS ARE YOU SINCERE ANDY WILLIAMS ARIVE DERCHE ROMA AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS AS LONG AS SHE NEEDS ME AS TIME GOES BY AT LAST MY LOVE HAS COME ALONG ETTA JAMES AT THE END OF THE RAINBOW AT THE HOP DANNY AND THE JUNIORS ATCHISON, TOPEKA, AND THE SANTA FE AUTUMN LEAVES OLDIES BUT GOODIES B TITLE ARTIST BABY BABY BABY DON'T SAY DON'T ELVIS PRESLEY BABY ELEPHANT WALK BABY I'M YOURS MAMA CASS BAND OF GOLD BARBARA ANN THE BEACH BOYS BECAUSE (YOU'VE COME TO ME) PERRY COMO BECAUSE OF YOU BEWITCHED, BOTHERED AND BEWILDERED BIG JOHN JIMMY DEAN BIG MAN FOUR PREPS BIRD DOG EVERLY BROTHERS BLAME IT ON THE BOSANOVA BLOWIN' IN THE WIND PETER PAUL & MARY BLUE HAWAII ELVIS PRESLEY BLUE -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun