THR 10805, Halls Hut, Halls Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glacial History of the Upper Mersey Valley

THE GLACIAL HISTORY OF THE UPPER MERSEY VALLEY by A a" D. G. Hannan, B.Sc., B. Ed., M. Ed. (Hons.) • Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science UNIVERSITY OF TASMANIA HOBART February, 1989 CONTENTS Summary of Figures and Tables Acknowledgements ix Declaration ix Abstract 1 Chapter 1 The upper Mersey Valley and adjacent areas: geographical 3 background Location and topography 3 Lithology and geological structure of the upper Mersey region 4 Access to the region 9 Climate 10 Vegetation 10 Fauna 13 Land use 14 Chapter 2 Literature review, aims and methodology 16 Review of previous studies of glaciation in the upper Mersey 16 region Problems arising from the literature 21 Aims of the study and methodology 23 Chapter $ Landforms produced by glacial and periglacial processes 28 Landforms of glacial erosion 28 Landforms of glacial deposition 37 Periglacial landforms and deposits 43 Chapter 4 Stratigraphic relationships between the Rowallan, Arm and Croesus glaciations 51 Regional stratigraphy 51 Weathering characteristics of the glacial, glacifluvial and solifluction deposits 58 Geographic extent and location of glacial sediments 75 Chapter 5 The Rowallan Glaciation 77 The extent of Rowallan Glaciation ice 77 Sediments associated with Rowallan Glaciation ice 94 Directions of ice movement 106 Deglaciation of Rowallan Glaciation ice 109 The age of the Rowallan Glaciation 113 Climate during the Rowallan Glaciation 116 Chapter The Arm, Croesus and older glaciations 119 The Arm Glaciation 119 The Croesus Glaciation 132 Tertiary Glaciation 135 Late Palaeozoic Glaciation 136 Chapter 7 Conclusions 139 , Possible correlations of other glaciations with the upper Mersey region 139 Concluding remarks 146 References 153 Appendix A INDEX OF FIGURES AND TABLES FIGURES Follows page Figure 1: Location of the study area. -

DRAFT Tasmanian Inland Recreational Fishery Management Plan 2018-28

DRAFT Tasmanian Inland Recreational Fishery Management Plan 2018-28 DRAFT Tasmanian Inland Recreational Fishery Management Plan 2018-28 Minister’s message It is my pleasure to release the Draft Tasmanian Inland Recreational Fishery Management Plan 2018-28 as the guiding document for the Inland Fisheries Service in managing this valuable resource on behalf of all Tasmanians for the next 10 years. The plan creates opportunities for anglers, improves access, ensures sustainability and encourages participation. Tasmania’s tradition with trout fishing spans over 150 years. It is enjoyed by local and visiting anglers in the beautiful surrounds of our State. Recreational fishing is a pastime and an industry; it supports regional economies providing jobs in associated businesses and tourism enterprises. A sustainable trout fishery ensures ongoing benefits to anglers and the community as a whole. To achieve sustainable fisheries we need careful management of our trout stocks, the natural values that support them and measures to protect them from diseases and pest fish. This plan simplifies regulations where possible by grouping fisheries whilst maintaining trout stocks for the future. Engagement and agreements with land owners and water managers will increase access and opportunities for anglers. The Tasmanian fishery caters for anglers of all skill levels and fishing interests. This plan helps build a fishery that provides for the diversity of anglers and the reasons they choose to fish. Jeremy Rockliff, Minister for Primary Industries and Water at the Inland Fisheries Service Trout Weekend 2017 (Photo: Brad Harris) DRAFT Tasmanian Inland Recreational Fishery Management Plan 2018-2028 FINAL.docx Page 2 of 27 DRAFT Tasmanian Inland Recreational Fishery Management Plan 2018-28 Contents Minister’s message ............................................................................................................... -

Western Lakes Fishery Management Plan 2002

Wilderness Fishery Western Lakes Western November 2002 F ISHERY M ANAGEMENT P LAN WESTERN LAKES WESTERN LAKES F ISHERY M ANAGEMENT P LAN November 2002 November 2002 Western Lakes – Fishery Management Plan Western Lakes – Fishery Management Plan November 2002 Executive Summary Introduction This fishery management plan is a subsidiary plan under the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan (WHA plan). The plan covers all areas of responsibility for which the Inland Fisheries Service (IFS) has statutory control; freshwater native species, freshwater recreational fisheries, and freshwater commercial fisheries. The plan also makes several recommendations on land management issues for consideration by the Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS). The area covered by the plan includes the Central Plateau Conservation Area west of the Lake Highway and the Walls of Jerusalem National Park, both of which lie within the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Environment This section examines the impacts of users (primarily anglers) on the environment and specifically water quality, and how these impacts can be minimised while maintaining angling opportunities. Management prescriptions focus on monitoring and review of water quality and the impacts of boating, wading and weir construction in various waters, and where necessary, implementing remediation measures. An information and education approach with the particular emphasis on the use of signage, will play an important role. Establishment of alternative boating access outside of the Western Lakes, development of a boating code of practice and review of current boating regulations will assist in minimising boating impacts. Additionally, the IFS will encourage and support studies that examine the impacts of boating and wading. -

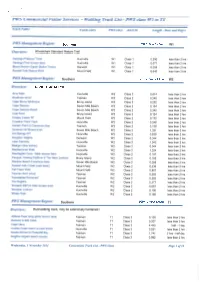

Walking Track List - PWS Class Wl to T4

PWS Commercial Visitor Services - Walking Track List - PWS class Wl to T4 Track Name FieldCentre PWS class AS2156 Length - Kms and Days PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: VV1 Overview: Wheelchair Standard Nature Trail Hastings Platypus Track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.290 less than 2 hrs Hastings Pool access track Huonville W1 Class 1 0.077 less than 2 hrs Mount Nelson Signal Station Tracks Derwent W1 Class 1 0.059 less than 2 hrs Russell Falls Nature Walk Mount Field W1 Class 1 0.649 less than 2 hrs PWS Management Region: Southern PWS Track Class: W2 Overview: Standard Nature Trail Arve Falls Huonville W2 Class 2 0.614 less than 2 hrs Blowhole circuit Tasman W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Cape Bruny lighthouse Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.252 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.154 less than 2 hrs Cape Deslacs Beach Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 0.345 less than 2 hrs Coal Point Bruny Island W2 Class 2 0.124 less than 2 hrs Creepy Crawly NT Mount Field W2 Class 2 0.175 less than 2 hrs Crowther Point Track Huonville W2 Class 2 0.248 less than 2 hrs Garden Point to Carnarvon Bay Tasman W2 Class 2 3.138 less than 2 hrs Gordons Hill fitness track Seven Mile Beach W2 Class 2 1.331 less than 2 hrs Hot Springs NT Huonville W2 Class 2 0.839 less than 2 hrs Kingston Heights Derwent W2 Class 2 0.344 less than 2 hrs Lake Osbome Huonville W2 Class 2 1.042 less than 2 hrs Maingon Bay lookout Tasman W2 Class 2 0.044 less than 2 hrs Needwonnee Walk Huonville W2 Class 2 1.324 less than 2 hrs Newdegate Cave - Main access -

To the Westward’

‘To The Westward’ Meander Valley Heritage Study Stage 1: Thematic History Prepared by Ian Terry & Kathryn Evans for Meander Valley Municipal Council October 2004 © Meander Valley Municipal Council Cover. Looking west to Mother Cummings Peak and the Great Western Tiers from Stockers Plains in 1888 (Tasmaniana Library, State Library of Tasmania) C O N T E N T S The Study Area.......................................................................................................................................1 The Study ...............................................................................................................................................2 Authorship ..............................................................................................................................................2 Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................2 Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................................................2 Abbreviations .........................................................................................................................................3 Historical Context .................................................................................................................................4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................4 -

Western Lakes Anglers Access

EDITION 5 Native Fish Western Lakes The Western Lakes area is home to four species of native fish; the Climbing galaxias, Spotted galaxias, Wilderness Fishery Clarence galaxias and the Western paragalaxias. The Western paragalaxias (Paragalaxias julianus) is a State and Commonwealth listed threatened fish found only Part of the Tasmanian Wilderness within the Western Lakes area in the Ouse, James and World Heritage Area Little Pine river systems. While the Western paragalaxias co-exists with trout, they are far more abundant in waters that are trout free. There are also a number of Anglers invertebrate species that are unique to the region. To assist in the protection of these species it is an offence to use fish or fish products as bait or to transfer any fish Access species or other organisms between waters. Western paragalaxias REGION: CENTRAL (Paragalaxias julianus) Matt Daniel • Report any unusual fish captures or algal sightings immediately to the Inland Fisheries Service • Report illegal activities to Bushwatch 1800 333 000 Code of Conduct • Be aware of and comply with fishing regulations. • Respect the rights of other anglers and users. • Protect the environment – this is a World Heritage Area. • Carefully return undersized, protected or unwanted catch back to the water. CONTACT DETAILS • Fish species and other organisms must not be relocated or transferred into other water bodies. 17 Back River Road, New Norfolk, 7140 Ph: 1300 INFISH www.ifs.tas.gov.au BL11369 Inland Fisheries Service Introduction 4WD tracks to Talinah Lagoon, Lake Pillans and the Julian Angling Notes Lakes are open at certain times of the year. -

FOI 180903 Document 1

DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND ENERGY To: James Barker, Assistant Secretary, Assessments and Governance Branch Referral Decision Brief - Halls Island Standing Camp, Lake Malbena, Tasmania (EPBC 2018/8177) Timing: 2 July 2018 - Statutory timeframe Recommended NCA [gJ NCA(pm) D CAD Decision Person proposing Wild Drake Pty Ltd the action Controlling World Heritage (s12 & s15A) National Heritage (s15B & s15C) Provisions Yes D No [gJ No if PM D Yes D No [gJ No if PM D triggered or matters protected Threatened Species & by particular Ramsar wetland (s16 & s17B) Communities (s18 & s18A) manner Yes D No [gJ No if PM D Yes D No [gJ No if PM D Migratory Species (s20 & s20A) C'wealth marine (s23 & 24A) YesD No~ NoifPMD YesD No[gJ NoifPMD Nuclear actions (s21 & 22A) C'wealth land (s26 & s27A) Yes D No [gJ No if PM D Yes D No [gJ No if PM D C'wealth actions (s28) GBRMP (s24B & s24C)* YesD No[gJ NoifPMD Yes D No [gJ No if PM D A water resource -large coal C'wealth heritage o/s (s27B & mines and CSG (s24D & s24E) 27C) YesD No[gJ NoifPMD YesD No[gJ NoifPMD Public Comments Yes [gJ No D Number: 940 See Attachment F Ministerial Yes [gJ No D Who: Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Comments Water and Environment. See Attachment G Recommendation/s: 1. Consider the information in this brief, the referral (Attachment A) and other attachments. ~idere 1 Please discuss 2. Agree with the recommended decision. ~otagreed 3. If you agree to 2, indicate that you accept the reasoning in the departmental briefing package as the basis for your decision. -

Fishing Code 2015-16

THE ESSENTIAL POCKET GUIDE TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2015-16 $6.00 concession entry fee for all Full Season Licence holders during the 2015/2016 season www.salmonponds.com.au Contents Contacts 4-5 Important season dates 6 Regulation changes 6 Licence information 7 Rules and regulations 11 Exceptions to the general rule 17-18 Exceptions to the general rules chart 19-20, 25-28 Boating information 29-31 Inland Fisheries Officers 32 Protecting the fishery and environment 35-39 Anglers Alliance Tasmania 39 Trout Guides 40 Cover photo courtesy of Brad Harris - 2015 THE TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2015 -16 PAGE 3 Contacts Inland Fisheries Service contacts Head Office 17 Back River Rd, New Norfolk, Tasmania 7140 PO Box 575, New Norfolk, Tasmania 7140 Phone (03) 6165 3808 1300 INFISH (1300 463 474) Fax (03) 6261 8051 Email [email protected] Website www.ifs.tas.gov.au Manager, Compliance and Operations 0438 338 530 Liawenee Field Station (03) 6259 8166 Lake Crescent Field Station (03) 6254 0058 THE TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2015 -16 PAGE 4 Other contacts Anglers Alliance Tasmania www.anglersalliance.org.au Bureau of Meteorology www.bom.gov.au Bushwatch 131 444 Devil facial tumour disease (03) 6165 4300 Emergency Animal Disease hotline 1800 675 888 Hydro Tasmania (lake levels) www.hydro.com.au Hydro Tasmania 1300 360 441 Marine and Safety Tasmania 1300 135 513 Orphaned or injured wildlife (03) 6165 4305 Parks and Wildlife Service (PWS) 1300 827 727 PWS Mole Creek (Central Plateau) (03) 6363 5133 Quarantine Tasmania (03) 6165 3777 Report -

2531 WHA Man Folder Cover

Tasmanian Wilderness Tasmanian World Heritage Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area MANAGEMENT PLAN 1999 Area Wilderness MANAGEMENT World Heritage PLAN 1999 Area “To identify, protect, conserve, present and, where appropriate, rehabilitate the world heritage and other natural and cultural values of the WHA, and to transmit that heritage to future generations in as good or better condition than at present.” WHA Management Plan, Overall Objective, 1999 MANAGEMENT PLAN PARKS PARKS and WILDLIFE and WILDLIFE SERVICE 1999 SERVICE ISBN 0 7246 2058 3 Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area PARKS MANAGEMENT PLAN and WILDLIFE 1999 SERVICE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA MANAGEMENT PLAN 1999 This management plan replaces the Tasmanian Abbreviations and General Terms Wilderness World Heritage Area Management The meanings of abbreviations and general terms Plan 1992, in accordance with Section 19(1) of the used throughout this plan are given below. National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970. A glossary of technical terms and phrases is The plan covers those parts of the Tasmanian provided on page 206. Wilderness World Heritage Area and 21 adjacent the Director areas (see table 2, page 15) reserved under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970 and has been The term ‘Director’ refers to the Director of prepared in accordance with the requirements of National Parks and Wildlife, a statutory position Part IV of that Act. held by the Director of the Parks and Wildlife Service. The draft of this plan (Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan 1997 the Minister Draft) was available for public comment from 14 The ‘Minister’ refers to the Minister administering November 1997 until 16 January 1998. -

Walls of Jerusalem Recreation Zone Plan

RECREATION ZONE PLAN 2013 Walls of Jerusalem NATIONAL PARK Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Walls of Jerusalem National Park Recreation Zone Plan 2013 Walls of Jerusalem National Park Recreation Zone Plan 2013 This Recreation Zone Plan has been prepared under the provisions of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Management Plan 1999, which is a management plan prepared in accordance with the National Parks and Reserves Management Act 2002. It aims to describe current and emerging issues and identify and provide for the appropriate level of facilities, management, interpretation, and commercial use of the Walls of Jerusalem area. The Tasmanian Reserve Management Code of Practice 2003 specifies appropriate standards and practices for new activities in reserves which have been approved through project planning and assessment processes. It also provides best practice operational standards. The Guiding Principles and Basic Approach specified in the Tasmanian Reserve Management Code of Practice 2003 have been adopted in the development of this recreation zone plan and will be applied in the conduct of operational management activities. Acknowledgement Many people have assisted in the preparation of this plan with ideas, feedback and information. Their time and effort is gratefully acknowledged. ISBN 978-0-9875827-4-4 (print version) ISBN 978-0-9875827-5-1 (pdf version) © Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment 2013 Cover image: Solomons Throne from Damascus Gate. Published by: Parks and Wildlife Service Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment GPO Box 1751 Hobart TAS 7001 Cite as: Parks and Wildlife Service (2013), Walls of Jerusalem Recreation Zone Plan, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart. -

TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2018-19 PAGE 2 Wear Your Life Jacket

TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2 0 1 8 - 1 9 THE ESSENTIAL POCKET GUIDE Introducing the... In sh App Access all the essentials for your shing needs: Find out where you can sh and how to get there Buy a shing licence Discover which regulations apply to different waters Find out what sh have been stocked where Check up to date weather observations, weather forecasts and warnings for all waters FREE! View lake levels and lake web cams Available from the App store and Google playstore for both iPhone and Android devices www.ifs.tas.gov.au THE TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2018-19 PAGE 2 Wear your life jacket Know how your life jacket works Go easy on the drink - stay under .05 Check the weather THE TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2018-19 PAGE 3 Visit the IFS online shop today to purchase all your... trout fishing mementos Medallions Posters Car and boat stickers Books Huon pine boxes Cheese boards & knives Zingers Coffee mugs Revolving (Lazy Susan) platters Coasters Lots of great gift ideas for family and friends www.ifs.tas.gov.au THE TASMANIAN INLAND FISHING CODE 2018-19 PAGE 4 Fisheries Habitat Improvement Fund PROTECT OUR HERITAGE The Fund has been established as a public, non-profit Trust to generate money for practical studies and works aimed at improving and restoring habitat for fish and other aquatic life. Contributions are being sought from corporations, government agencies, community organisations and private individuals. RESTORE THE HABITAT Although the focus of the Fund is on improving freshwater habitats, a key outcome is improved fishing for the angler. -

Conservation of Freshwater Ecosystem Values (CFEV) Database � Metadata

Conservation of Freshwater Ecosystem Values (CFEV) Database - Metadata Contents Abstraction index ........................................................................................................ 1 Acid mine drainage .................................................................................................... 5 Area ........................................................................................................................... 7 Burrowing crayfish regions ......................................................................................... 8 Catchment disturbance .............................................................................................. 9 Conservation Management Priority – Immediate ...................................................... 14 Conservation Management Priority – Potential ......................................................... 17 Crayfish regions ....................................................................................................... 19 Digital elevation model ............................................................................................. 23 Elevation .................................................................................................................. 24 Estuaries .................................................................................................................. 25 Estuaries biophysical classification ........................................................................... 26 Estuaries naturalness ..............................................................................................