Arxiv:Math/0208146V4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1111: Linear Algebra I

1111: Linear Algebra I Dr. Vladimir Dotsenko (Vlad) Lecture 11 Dr. Vladimir Dotsenko (Vlad) 1111: Linear Algebra I Lecture 11 1 / 13 Previously on. Theorem. Let A be an n × n-matrix, and b a vector with n entries. The following statements are equivalent: (a) the homogeneous system Ax = 0 has only the trivial solution x = 0; (b) the reduced row echelon form of A is In; (c) det(A) 6= 0; (d) the matrix A is invertible; (e) the system Ax = b has exactly one solution. A very important consequence (finite dimensional Fredholm alternative): For an n × n-matrix A, the system Ax = b either has exactly one solution for every b, or has infinitely many solutions for some choices of b and no solutions for some other choices. In particular, to prove that Ax = b has solutions for every b, it is enough to prove that Ax = 0 has only the trivial solution. Dr. Vladimir Dotsenko (Vlad) 1111: Linear Algebra I Lecture 11 2 / 13 An example for the Fredholm alternative Let us consider the following question: Given some numbers in the first row, the last row, the first column, and the last column of an n × n-matrix, is it possible to fill the numbers in all the remaining slots in a way that each of them is the average of its 4 neighbours? This is the \discrete Dirichlet problem", a finite grid approximation to many foundational questions of mathematical physics. Dr. Vladimir Dotsenko (Vlad) 1111: Linear Algebra I Lecture 11 3 / 13 An example for the Fredholm alternative For instance, for n = 4 we may face the following problem: find a; b; c; d to put in the matrix 0 4 3 0 1:51 B 1 a b -1C B C @0:5 c d 2 A 2:1 4 2 1 so that 1 a = 4 (3 + 1 + b + c); 1 8b = 4 (a + 0 - 1 + d); >c = 1 (a + 0:5 + d + 4); > 4 < 1 d = 4 (b + c + 2 + 2): > > This is a system with 4:> equations and 4 unknowns. -

New Algorithms in the Frobenius Matrix Algebra for Polynomial Root-Finding

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Computer Science Technical Reports CUNY Academic Works 2014 TR-2014006: New Algorithms in the Frobenius Matrix Algebra for Polynomial Root-Finding Victor Y. Pan Ai-Long Zheng How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_cs_tr/397 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] New Algoirthms in the Frobenius Matrix Algebra for Polynomial Root-finding ∗ Victor Y. Pan[1,2],[a] and Ai-Long Zheng[2],[b] Supported by NSF Grant CCF-1116736 and PSC CUNY Award 64512–0042 [1] Department of Mathematics and Computer Science Lehman College of the City University of New York Bronx, NY 10468 USA [2] Ph.D. Programs in Mathematics and Computer Science The Graduate Center of the City University of New York New York, NY 10036 USA [a] [email protected] http://comet.lehman.cuny.edu/vpan/ [b] [email protected] Abstract In 1996 Cardinal applied fast algorithms in Frobenius matrix algebra to complex root-finding for univariate polynomials, but he resorted to some numerically unsafe techniques of symbolic manipulation with polynomials at the final stages of his algorithms. We extend his work to complete the computations by operating with matrices at the final stage as well and also to adjust them to real polynomial root-finding. Our analysis and experiments show efficiency of the resulting algorithms. 2000 Math. -

Cohomological Approach to the Graded Berezinian

J. Noncommut. Geom. 9 (2015), 543–565 Journal of Noncommutative Geometry DOI 10.4171/JNCG/200 © European Mathematical Society Cohomological approach to the graded Berezinian Tiffany Covolo n Abstract. We develop the theory of linear algebra over a .Z2/ -commutative algebra (n N), which includes the well-known super linear algebra as a special case (n 1). Examples of2 such graded-commutative algebras are the Clifford algebras, in particularD the quaternion algebra H. Following a cohomological approach, we introduce analogues of the notions of trace and determinant. Our construction reduces in the classical commutative case to the coordinate-free description of the determinant by means of the action of invertible matrices on the top exterior power, and in the supercommutative case it coincides with the well-known cohomological interpretation of the Berezinian. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010). 16W50, 17A70, 11R52, 15A15, 15A66, 16E40. Keywords. Graded linear algebra, graded trace and Berezinian, quaternions, Clifford algebra. 1. Introduction Remarkable series of algebras, such as the algebra of quaternions and, more generally, Clifford algebras turn out to be graded-commutative. Originated in [1] and [2], this idea was developed in [10] and [11]. The grading group in this case is n 1 .Z2/ C , where n is the number of generators, and the graded-commutativity reads as a;b ab . 1/hQ Qiba (1.1) D n 1 where a; b .Z2/ C denote the degrees of the respective homogeneous elements Q Q 2 n 1 n 1 a and b, and ; .Z2/ C .Z2/ C Z2 is the standard scalar product of binary .n 1/h-vectorsi W (see Section 2). -

Subspace-Preserving Sparsification of Matrices with Minimal Perturbation

Subspace-preserving sparsification of matrices with minimal perturbation to the near null-space. Part I: Basics Chetan Jhurani Tech-X Corporation 5621 Arapahoe Ave Boulder, Colorado 80303, U.S.A. Abstract This is the first of two papers to describe a matrix sparsification algorithm that takes a general real or complex matrix as input and produces a sparse output matrix of the same size. The non-zero entries in the output are chosen to minimize changes to the singular values and singular vectors corresponding to the near null-space of the input. The output matrix is constrained to preserve left and right null-spaces exactly. The sparsity pattern of the output matrix is automatically determined or can be given as input. If the input matrix belongs to a common matrix subspace, we prove that the computed sparse matrix belongs to the same subspace. This works with- out imposing explicit constraints pertaining to the subspace. This property holds for the subspaces of Hermitian, complex-symmetric, Hamiltonian, cir- culant, centrosymmetric, and persymmetric matrices, and for each of the skew counterparts. Applications of our method include computation of reusable sparse pre- conditioning matrices for reliable and efficient solution of high-order finite element systems. The second paper in this series [1] describes our open- arXiv:1304.7049v1 [math.NA] 26 Apr 2013 source implementation, and presents further technical details. Keywords: Sparsification, Spectral equivalence, Matrix structure, Convex optimization, Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse Email address: [email protected] (Chetan Jhurani) Preprint submitted to Computers and Mathematics with Applications October 10, 2018 1. Introduction We present and analyze a matrix-valued optimization problem formulated to sparsify matrices while preserving the matrix null-spaces and certain spe- cial structural properties. -

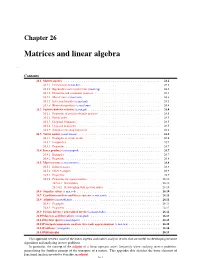

Matrices and Linear Algebra

Chapter 26 Matrices and linear algebra ap,mat Contents 26.1 Matrix algebra........................................... 26.2 26.1.1 Determinant (s,mat,det)................................... 26.2 26.1.2 Eigenvalues and eigenvectors (s,mat,eig).......................... 26.2 26.1.3 Hermitian and symmetric matrices............................. 26.3 26.1.4 Matrix trace (s,mat,trace).................................. 26.3 26.1.5 Inversion formulas (s,mat,mil)............................... 26.3 26.1.6 Kronecker products (s,mat,kron).............................. 26.4 26.2 Positive-definite matrices (s,mat,pd) ................................ 26.4 26.2.1 Properties of positive-definite matrices........................... 26.5 26.2.2 Partial order......................................... 26.5 26.2.3 Diagonal dominance.................................... 26.5 26.2.4 Diagonal majorizers..................................... 26.5 26.2.5 Simultaneous diagonalization................................ 26.6 26.3 Vector norms (s,mat,vnorm) .................................... 26.6 26.3.1 Examples of vector norms.................................. 26.6 26.3.2 Inequalities......................................... 26.7 26.3.3 Properties.......................................... 26.7 26.4 Inner products (s,mat,inprod) ................................... 26.7 26.4.1 Examples.......................................... 26.7 26.4.2 Properties.......................................... 26.8 26.5 Matrix norms (s,mat,mnorm) .................................... 26.8 26.5.1 -

A Logarithmic Minimization Property of the Unitary Polar Factor in The

A logarithmic minimization property of the unitary polar factor in the spectral norm and the Frobenius matrix norm Patrizio Neff∗ Yuji Nakatsukasa† Andreas Fischle‡ October 30, 2018 Abstract The unitary polar factor Q = Up in the polar decomposition of Z = Up H is the minimizer over unitary matrices Q for both Log(Q∗Z) 2 and its Hermitian part k k sym (Log(Q∗Z)) 2 over both R and C for any given invertible matrix Z Cn×n and k * k ∈ any matrix logarithm Log, not necessarily the principal logarithm log. We prove this for the spectral matrix norm for any n and for the Frobenius matrix norm in two and three dimensions. The result shows that the unitary polar factor is the nearest orthogonal matrix to Z not only in the normwise sense, but also in a geodesic distance. The derivation is based on Bhatia’s generalization of Bernstein’s trace inequality for the matrix exponential and a new sum of squared logarithms inequality. Our result generalizes the fact for scalars that for any complex logarithm and for all z C 0 ∈ \ { } −iϑ 2 2 −iϑ 2 2 min LogC(e z) = log z , min Re LogC(e z) = log z . ϑ∈(−π,π] | | | | || ϑ∈(−π,π] | | | | || Keywords: unitary polar factor, matrix logarithm, matrix exponential, Hermitian part, minimization, unitarily invariant norm, polar decomposition, sum of squared logarithms in- equality, optimality, matrix Lie-group, geodesic distance arXiv:1302.3235v4 [math.CA] 2 Jan 2014 AMS 2010 subject classification: 15A16, 15A18, 15A24, 15A44, 15A45, 26Dxx ∗Corresponding author, Head of Lehrstuhl f¨ur Nichtlineare Analysis und Modellierung, Fakult¨at f¨ur Mathematik, Universit¨at Duisburg-Essen, Campus Essen, Thea-Leymann Str. -

Determinants

12 PREFACECHAPTER I DETERMINANTS The notion of a determinant appeared at the end of 17th century in works of Leibniz (1646–1716) and a Japanese mathematician, Seki Kova, also known as Takakazu (1642–1708). Leibniz did not publish the results of his studies related with determinants. The best known is his letter to l’Hospital (1693) in which Leibniz writes down the determinant condition of compatibility for a system of three linear equations in two unknowns. Leibniz particularly emphasized the usefulness of two indices when expressing the coefficients of the equations. In modern terms he actually wrote about the indices i, j in the expression xi = j aijyj. Seki arrived at the notion of a determinant while solving the problem of finding common roots of algebraic equations. In Europe, the search for common roots of algebraic equations soon also became the main trend associated with determinants. Newton, Bezout, and Euler studied this problem. Seki did not have the general notion of the derivative at his disposal, but he actually got an algebraic expression equivalent to the derivative of a polynomial. He searched for multiple roots of a polynomial f(x) as common roots of f(x) and f (x). To find common roots of polynomials f(x) and g(x) (for f and g of small degrees) Seki got determinant expressions. The main treatise by Seki was published in 1674; there applications of the method are published, rather than the method itself. He kept the main method in secret confiding only in his closest pupils. In Europe, the first publication related to determinants, due to Cramer, ap- peared in 1750. -

A Proof of the Multiplicative Property of the Berezinian ∗

Morfismos, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2008, pp. 45–61 A proof of the multiplicative property of the Berezinian ∗ Manuel Vladimir Vega Blanco Abstract The Berezinian is the analogue of the determinant in super-linear algebra. In this paper we give an elementary and explicative proof that the Berezinian is a multiplicative homomorphism. This paper is self-conatined, so we begin with a short introduction to super- algebra, where we study the category of supermodules. We write the matrix representation of super-linear transformations. Then we can define a concept analogous to the determinant, this is the superdeterminant or Berezinian. We finish the paper proving the multiplicative property. 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification: 81R99. Keywords and phrases: Berezinian, superalgebra, supergeometry, super- calculus. 1 Introduction Linear superalgebra arises in the study of elementary particles and its fields, specially with the introduction of super-symmetry. In nature we can find two classes of elementary particles, in accordance with the statistics of Einstein-Bose and the statistics of Fermi, the bosons and the fermions, respectively. The fields that represent it have a parity, there are bosonic fields (even) and fermionic fields (odd): the former commute with themselves and with the fermionic fields, while the latter anti-commute with themselves. This fields form an algebra, and with the above non-commutativity property they form an algebraic structure ∗Research supported by a CONACyT scholarship. This paper is part of the autor’s M. Sc. thesis presented at the Department of Mathematics of CINVESTAV-IPN. 45 46 Manuel Vladimir Vega Blanco called a which we call a superalgebra. -

Moments of Logarithmic Derivative SO

Alvarez, E. , & Snaith, N. C. (2020). Moments of the logarithmic derivative of characteristic polynomials from SO(2N) and USp(2N). Journal of Mathematical Physics, 61, [103506 (2020)]. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0008423, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0008423 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1063/5.0008423 10.1063/5.0008423 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via American Institute of Physics at https://aip.scitation.org/doi/10.1063/5.0008423 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Moments of the logarithmic derivative of characteristic polynomials from SO(N) and USp(2N) E. Alvarez1, a) and N.C. Snaith1, b) School of Mathematics, University of Bristol, UK We study moments of the logarithmic derivative of characteristic polynomials of orthogonal and symplectic random matrices. In particular, we compute the asymptotics for large matrix size, N, of these moments evaluated at points which are approaching 1. This follows work of Bailey, Bettin, Blower, Conrey, Prokhorov, Rubinstein and Snaith where they compute these asymptotics in the case of unitary random matrices. a)Electronic mail: [email protected] b)Electronic mail (Corresponding author): [email protected] 1 I. -

Perron–Frobenius Theorem for Matrices with Some Negative Entries

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Linear Algebra and its Applications 328 (2001) 57–68 www.elsevier.com/locate/laa Perron–Frobenius theorem for matrices with some negative entries Pablo Tarazaga a,∗,1, Marcos Raydan b,2, Ana Hurman c aDepartment of Mathematics, University of Puerto Rico, P.O. Box 5000, Mayaguez Campus, Mayaguez, PR 00681-5000, USA bDpto. de Computación, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Central de Venezuela, Ap. 47002, Caracas 1041-A, Venezuela cFacultad de Ingeniería y Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Universidad Nacional del Cuyo, Mendoza, Argentina Received 17 December 1998; accepted 24 August 2000 Submitted by R.A. Brualdi Abstract We extend the classical Perron–Frobenius theorem to matrices with some negative entries. We study the cone of matrices that has the matrix of 1’s (eet) as the central ray, and such that any matrix inside the cone possesses a Perron–Frobenius eigenpair. We also find the maximum angle of any matrix with eet that guarantees this property. © 2001 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: Perron–Frobenius theorem; Cones of matrices; Optimality conditions 1. Introduction In 1907, Perron [4] made the fundamental discovery that the dominant eigenvalue of a matrix with all positive entries is positive and also that there exists a correspond- ing eigenvector with all positive entries. This result was later extended to nonnegative matrices by Frobenius [2] in 1912. In that case, there exists a nonnegative dominant ∗ Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (P. Tarazaga), [email protected] (M. -

1 1.1. the DFT Matrix

FFT January 20, 2016 1 1.1. The DFT matrix. The DFT matrix. By definition, the sequence f(τ)(τ = 0; 1; 2;:::;N − 1), posesses a discrete Fourier transform F (ν)(ν = 0; 1; 2;:::;N − 1), given by − 1 NX1 F (ν) = f(τ)e−i2π(ν=N)τ : (1.1) N τ=0 Of course, this definition can be immediately rewritten in the matrix form as follows 2 3 2 3 F (1) f(1) 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 7 6 F (2) 7 1 6 f(2) 7 6 . 7 = p F 6 . 7 ; (1.2) 4 . 5 N 4 . 5 F (N − 1) f(N − 1) where the DFT (i.e., the discrete Fourier transform) matrix is defined by 2 3 1 1 1 1 · 1 6 − 7 6 1 w w2 w3 ··· wN 1 7 6 7 h i 6 1 w2 w4 w6 ··· w2(N−1) 7 1 − − 1 6 7 F = p w(k 1)(j 1) = p 6 3 6 9 ··· 3(N−1) 7 N 1≤k;j≤N N 6 1 w w w w 7 6 . 7 4 . 5 1 wN−1 w2(N−1) w3(N−1) ··· w(N−1)(N−1) (1.3) 2πi with w = e N being the primitive N-th root of unity. 1.2. The IDFT matrix. To recover N values of the function from its discrete Fourier transform we simply have to invert the DFT matrix to obtain 2 3 2 3 f(1) F (1) 6 7 6 7 6 f(2) 7 p 6 F (2) 7 6 7 −1 6 7 6 . -

Logarithmic Growth and Frobenius Filtrations for Solutions of P-Adic

Logarithmic growth and Frobenius filtrations for solutions of p-adic differential equations Bruno Chiarellotto∗ Nobuo Tsuzuki† Version of October 24, 2006 Abstract For a ∇-module M over the ring K[[x]]0 of bounded functions we define the notion of special and generic log-growth filtrations. Moreover, if M admits also a ϕ-structure then it is endowed also with generic and special Frobenius slope filtrations. We will show that in the case of M a ϕ-∇-module of rank 2, the two filtrations coincide. We may then extend such a result also for a module defined on an open set of the projective line. This generalizes previous results of Dwork about the coincidences between the log-growth of the solutions of hypergeometric equations and the Frobenius slopes. Contents 1 Log-growth of solutions 7 2 ϕ-modules over a p-adically complete discrete valuation field 9 3 Log-growth filtration over E and E 15 4 Generic and special log-growth filtrations 19 5 Examples 21 6 Generic and special Frobenius slope filtrations 26 7 Comparison between log-growth filtration and Frobenius filtration. The rank 2 case 29 Introduction The meaningful connections in the p-adic setting are those with a good radius of conver- gence for their solutions or horizontal sections. In general this condition is referred as the condition of solvability and it is granted, for example, under the hypotheses of having a Frobenius structure. It has been noticed long time ago that the solutions do not have in ∗[email protected] †[email protected] 1 general the same growth in having their good radius of convergence.