Assessment of Canine Temperament: Predictive Or Prescriptive?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usaf Sentry Dog Manual

I 4 A I R AFM FORCE 125-6 MANUAL a _ / USAF SENTRY DOG MANUAL 15 MAY 1956 D EPA RT MEN T OF THE AIR FORCE ~374 AFM 125-6 AIR FORCE MANUAL DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR NUMBER 125-6 WASHINGTON, 1.5 M Foreword 1. Purpose and Scope. This manual prescribes the policies and proce- dures governing the operation and maintenance of the USAF Sentry Dog Program as established in AFR 125-9. 2. Contents. This manual covers the following elements of the USAF Sentry Dog Program: Qualifications, selection and training of handler per- sonnel; procurement, training and utilization of sentry dogs; and the pro- cedures for providing the necessary administrative, maintenance and logis- tical support. 3. Recommendations. Suggestions for the improvement of the Sentry Dog Program and the measures prescribed in this manual are encouraged. They may be submitted through proper channels to The Inspector General, Headquarters, USAF, Washington 25, D. C., Attention: The Provost Marshal. BY ORDER OF THE SECRETARY OF THE AIR FORCE: OFFICIAL N. F. TWINING Chief of Staff, United States Air Force E. E. TORO Colonel, USAF Air Adjutant General DISTRIBUTION Zone of Interior and Overseas: Headquarters USAF 150 Major air commands 8 Subordinate air commands 6 Bases 3 Squadrons (Air Police) 2 *Special * Commanders will requisition additional copies as required for issuing one copy to each dog handler. ~374 IS May 1956 AFM 125—6 Contents Page Chapter I —Background Section I—Origins of TJSAF Sentry Dog Program 1 Section Il—Objective of the Program 3 Chapter 2—Handler Personnel Section -

What Are Some of the Common Myths About Dog Training?

What are Some of the Common Myths About Dog Training? ith the wide variety of dog trainers available and the differing skills and educational levels, you will no doubt encounter a diverse set of opinions when talking to trainers, readingW their web sites and getting opinions from former clients, friends, and others. While the internet has been a great tool for education, it also has helped to propagate many myths about dog training. Here’s some of the common ones that you may hear in your search for a trainer. MYTH: If a dog can’t learn a behavior, he is either stubborn, dominant, stupid, or a combination of the three. REALITY: The truth is, dogs in many ways are just like people. Some dogs will pick things up very quickly and others will take more time and guidance. Often times when we as trainers see a dog having difficulty learning a task, it’s because the dog is not being communicated to in a way that the dog can understand. Other times they fail to learn a task because they are not properly instructed as to when they’ve done the behavior correctly and therefore have no way of knowing what you are asking of them . Always reward your dog for doing something right and use patience when demonstrating a desired behavior. If your dog still seems to have trouble learning something new, think about how you’ve been teaching the dog from the “dog’s point of view.” Think about how certain behaviors may not be as clearly taught as you thought they were, or if there are elements in the environment that might be causing your dog to become confused or distracted. -

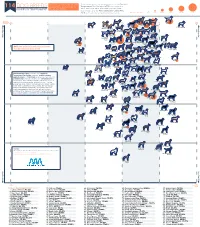

Ranked by Temperament

Comparing Temperament and Breed temperament was determined using the American 114 DOG BREEDS Popularity in Dog Breeds in Temperament Test Society's (ATTS) cumulative test RANKED BY TEMPERAMENT the United States result data since 1977, and breed popularity was determined using the American Kennel Club's (AKC) 2018 ranking based on total breed registrations. Number Tested <201 201-400 401-600 601-800 801-1000 >1000 American Kennel Club 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 1. Labrador 100% Popularity Passed 2. German Retriever Passed Shepherd 3. Mixed Breed 7. Beagle Dog 4. Golden Retriever More Popular 8. Poodle 11. Rottweiler 5. French Bulldog 6. Bulldog (Miniature)10. Poodle (Toy) 15. Dachshund (all varieties) 9. Poodle (Standard) 17. Siberian 16. Pembroke 13. Yorkshire 14. Boxer 18. Australian Terrier Husky Welsh Corgi Shepherd More Popular 12. German Shorthaired 21. Cavalier King Pointer Charles Spaniel 29. English 28. Brittany 20. Doberman Spaniel 22. Miniature Pinscher 19. Great Dane Springer Spaniel 24. Boston 27. Shetland Schnauzer Terrier Sheepdog NOTE: We excluded breeds that had fewer 25. Bernese 30. Pug Mountain Dog 33. English than 30 individual dogs tested. 23. Shih Tzu 38. Weimaraner 32. Cocker 35. Cane Corso Cocker Spaniel Spaniel 26. Pomeranian 31. Mastiff 36. Chihuahua 34. Vizsla 40. Basset Hound 37. Border Collie 41. Newfoundland 46. Bichon 39. Collie Frise 42. Rhodesian 44. Belgian 47. Akita Ridgeback Malinois 49. Bloodhound 48. Saint Bernard 45. Chesapeake 51. Bullmastiff Bay Retriever 43. West Highland White Terrier 50. Portuguese 54. Australian Water Dog Cattle Dog 56. Scottish 53. Papillon Terrier 52. Soft Coated 55. Dalmatian Wheaten Terrier 57. -

Behaviour Test for Eight-Week Old Puppies—Heritabilities of Tested

Applied Animal Behaviour Science 58Ž. 1998 151±162 Behaviour test for eight-week old puppiesÐheritabilities of tested behaviour traits and its correspondence to later behaviour Erik Wilsson a,), Per-Erik Sundgren b a Department of Zoology, Stockholm UniÕersity,S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Animal Breeding and Genetics, Swedish UniÕersity of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden Accepted 25 June 1997 Abstract In order to test if adult behaviour could be predicted at eight weeks of age, 630 German shepherd puppies were tested. All dogs were also tested at 450±600 days of age according to regimen used to select service dogs. Significant gender differences were found in 4 of the 10 score groups of the puppy test. There were also significant correlations between the puppy test score groups. Correspondence of puppy test results to performance at adult age was negligible and the puppy test was therefore not found useful in predicting adult suitability for service dog work. Heritability was medium high or high for behaviour characteristics of the score groups in the puppy test. Maternal effects on the puppy test results were found when comparing estimations based on sire and dam variances. It also suggests that maternal effects are more likely to be seen in juvenile than in adult behaviour. q 1998 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Dog; Behavioural test; Temperament; Genetics; Ontogeny 1. Introduction Puppy behavioural tests for different purposes have been presented. Scott and Fuller Ž.1965 in their work at Bar Harbor performed a large number of tests on puppies and young dogs, from birth up to the age of one year. -

Visit Two: Training and Socialization

Visit Two: Training and Socialization Clermont Animal Hospital, Inc. Introduction to Obedience Training 15 •• How often should I work on training my dog? 15 • Should I use rewards? 15 • Collars and Leads 15 • Basic Commands: Sit, Down, Stay, Come, and Heel 15 Puppy and Obedience Classes 18 •• Why should I take my puppy to obedience classes? 18 • What are the different types of obedience classes? 18 •• How do I choose a training facility? 19 Socializing your Puppy20 •• What is Socialization?20 •• Socialization with People 20 • Socialization with Other Animals 20 •• Environmental Exploration 21 Preventing Aggressive Behavior 22 • Why are dogs aggressive? 22 • Suggestions to Decrease Dominant and Aggressive Behavior 22 Training your Puppy to Accept Examination and Restraint 23 • Home Health Care 23 • Training your Puppy to Stand for Examination23 •• Training your Puppy to Accept Restraint 23 Introduction to Obedience Training Whether you work with your puppy on your own or take formal classes together, it is important that your puppy learns to obey basic commands. This will help you to keep your dog safe and to prevent your dog from being a problem to other people. Teaching your dog good “manners” will also strengthen your bond with your pet. Remember that repetition is the key to teaching your dog new commands and to reinforcing commands he or she has already learned. How often should I work on training my dog? Work with your dog every day. A few minutes of training a couple times a day can make a big difference. Should I use rewards? The veterinarians at Clermont Animal Hospital, Inc. -

Aggression in Dogs an Overview

Behavior & Training 415.506.6280 Available B&T Services Aggression in Dogs: An Overview What is the behavior? Aggression is a natural behavior, not an aberration. Most aggression is defensive in nature – that is, the dog is reacting to what he perceives as a threat. Behavior is always in flux, and can get worse before it gets better. If your dog is aggressive, you must decide: Whether your dog is too dangerous to work with. Whether the behavior can be kept under control by managing the environment. Whether you have the ability to modify the behavior. Whether you have the time and commitment to do so. Know your dog and his body language - from behind your dog as well as beside or in front. Dogs, after all, often walk ahead of their owner. (Please review our Body Language: Speaking “Dog” handout.) Observe your dog's body language when relaxed. Observe your dog's body language when tense. Observe the DISTANCE between your dog and the object of interest. Observe your dog's body language when he is about to attack. Observe EXACTLY what sets off your dog: children/other dogs/other male or female dogs/men with beards/people in uniform. Know your own response to stress. Note what you or your family members do when your dog looks like he might aggress or when you are worried while with your dog. How do you modify the behavior? This handout will discuss some of the reasons a dog may behave aggressively and is only an overview of aggressive displays. To build an individualized behavior modification program for your dog’s needs, please contact Behavior & Training to schedule a consultation. -

Comparative Study of Free-Roaming Domestic Dog Management and Roaming Behavior Across Four Countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 Comparative study of free-roaming domestic dog management and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda Warembourg, Charlotte ; Wera, Ewaldus ; Odoch, Terence ; Bulu, Petrus Malo ; Berger-González, Monica ; Alvarez, Danilo ; Abakar, Mahamat Fayiz ; Maximiano Sousa, Filipe ; Cunha Silva, Laura ; Alobo, Grace ; Bal, Valentin Dingamnayal ; López Hernandez, Alexis Leonel ; Madaye, Enos ; Meo, Maria Satri ; Naminou, Abakar ; Roquel, Pablo ; Hartnack, Sonja ; Dürr, Salome Abstract: Dogs play a major role in public health because of potential transmission of zoonotic diseases, such as rabies. Dog roaming behavior has been studied worldwide, including countries in Asia, Latin America, and Oceania, while studies on dog roaming behavior are lacking in Africa. Many of those studies investigated potential drivers for roaming, which could be used to refine disease control measures. However, it appears that results are often contradictory between countries, which could be caused by differences in study design or the influence of context-specific factors. Comparative studiesondog roaming behavior are needed to better understand domestic dog roaming behavior and address these discrepancies. The aim of this study was to investigate dog demography, management, and roaming behavior across four countries: Chad, Guatemala, Indonesia, and Uganda. We equipped 773 dogs with georeferenced contact sensors (106 in Chad, 303 in Guatemala, 217 in Indonesia, and 149 in Uganda) and interviewed the owners to collect information about the dog [e.g., sex, age, body condition score (BCS)] and its management (e.g., role of the dog, origin of the dog, owner-mediated transportation, confinement, vaccination, and feeding practices). -

Basic Commands and Training

Greyhounds: Basic Commands and Training Written by Susan McKeon, MAPDT, UK (01157) www.HappyHoundsTraining.co.uk Registered Charity Numbers 269688 & SC044047 ProvidingProviding bright bright futures futures and and loving loving homes home for forretired retired racing racing greyhounds greyhounds Importance of training Dog training should be fun for you and your greyhound. Everyone likes a well behaved and socialised dog and providing some basic training will help equip your greyhound to adjust to his life after racing and know what is expected of him in his new home. Positive training techniques Positive training works by rewarding our dogs for the behaviours we want and ignoring or preventing the behaviours we don’t want. By rewarding our dogs as soon as they perform the required behaviour (such as ‘Down’), we are letting them know they have performed the correct action and giving them a reason to repeat the behaviour next time we ask for it. Greyhounds are a sensitive breed and do not respond well to punishment. Using aversive training techniques such as shouting, physical punishment, or using rattle cans, will not teach your dog what you want him to do. It is more likely to make your dog fearful and cause other behaviour problems. Using rewards in training When you start teaching your dog, you need to reward him as soon as he has performed the required action. The type of rewards you use need to be something your dog really wants. This will vary from dog to dog and rewards can include food, praise, gentle petting and games with toys. -

Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY

Military Working Dog History Chapter 2 MILITARY WORKING DOG HISTORY NOLAN A. WATSON, MLA* INTRODUCTION COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR WORLD WAR I WORLD WAR II KOREAN WAR AND THE EARLY COLD WAR VIETNAM WAR THE MILITARY WORKING DOG CONCLUSION *Army Medical Department (AMEDD) Regimental Historian; AMEDD Center of History and Heritage, Medical Command, 2748 Worth Road, Suite 28, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, Texas 78234; formerly, Branch Historian, Military Police Corps, US Army Military Police School, Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri 83 Military Veterinary Services INTRODUCTION History books recount stories of dogs accompany- which grew and changed with subsequent US wars. ing ancient armies, serving as sources of companion- Currently, US forces utilize military working dogs ship and performing valuable sentry duties. Dogs also (MWDs) in a variety of professions such as security, fought in battle alongside their owners. Over time, law enforcement, combat tracking, and detection (ie, however, the role of canines as war dogs diminished, for explosives and narcotics). Considered an essential especially after firearms became part of commanders’ team member, an MWD was even included in the arsenals. By the 1800s and up until the early 1900s, the successful raid against Osama Bin Laden in 2011.1 (See horse rose to prominence as the most important mili- also Chapter 3, Military Working Dog Procurement, tary animal; at this time, barring some guard duties, Veterinary Care, and Behavioral Services for more dogs were relegated mostly to the role of mascots. It information about the historic transformation of the was not until World War II that the US Army adopted MWD program and the military services available broader roles for its canine service members—uses for canines.) COLONIAL AMERICA AND THE CIVIL WAR Early American Army dogs were privately owned tary continued throughout the next century and into at first; there was neither a procurement system to the American Civil War. -

2021 Michigan Black Bear Digest

2021 Michigan Black Bear Digest Reminders • NEW Season date changes for hunt periods 1 and 2; see page 11. • NEW Bait barrels no longer allowed on DNR-managed lands. • NEW Archery-only season in Baldwin and Gladwin bear management units. Drawing results available July 6. Application Period: May 1 - June 1, 2021 RAP (Report All Poaching): Call or text - (800)-292-7800 Table of Contents Managing Black Bears ......................................................................3 Black Bear Management ......................................................................3 Bear Drawing and Preference Point System .......................................5 2021 Hunting Information ................................................................6 How to Apply for a Limited License Hunt .............................................6 2021 Bear Hunts ................................................................................11 License Purchase ................................................................................14 Leftover Licenses ................................................................................15 Mentored Youth Hunting .....................................................................16 Apprentice Hunting License ...............................................................16 Bear Hunt Transfer Program ...............................................................17 Hunting Hours .....................................................................................18 Hunting Methods .................................................................................20 -

Train and Certify Service Dogs for Individuals with Disabilities”

Great Plains Assistance Dogs Foundation dba Service Dogs for America Types of service dogs PO Box 513 Jud, ND 58454 ABOUT SERVICE DOGS FOR AMERICA Service Dogs for America (SDA) trained its first service dog in 1989 and placed it with SDA’s first client in 1990. In 1992, SDA was officially designated as a 501(c) (3) nonprofit organization. SDA is an accredited service dog school member of Assistance Dogs International. The mission of SDA is to: “train and certify service dogs for individuals with disabilities” The following describes the different types of dogs trained and placed by SDA Mobility Assistance Dog Mobility Assistance Dog ‐ Task Training Assists with (but not limited to) the following types of diseases or Retrieve dropped object. injuries: Open interior/exterior doors. Amputation Retrieve a beverage, medication, or other item from Arthritis a refrigerator. Cerebral Palsy Bring medication and/or a beverage to a person on Multiple Sclerosis command or when alerted to do so by a Muscular Dystrophy timer/alarm. Paraplegia Help a person stand and brace. Parkinson’s Disease Stabilize during walking. Spina Bifida Assist in pulling a manual wheelchair. Stroke Turn lights on or off. Tetraplegia Pull/push/open door, drawer, or cupboard. Traumatic brain or spinal cord injury Operate handicap door switch. Retrieve a phone or other specified object to person’s hand or lap. Get help by alerting another person in the environment. Activate an electronic alert system. Assist a person in removing/putting on clothing. Carry medication, wallet, etc. Dog can perform skills while client is using adaptive equipment such as a wheelchair, scooter, walker or specialized leash or harness. -

Assessment of Canine Temperament in Relation to Breed Groups 5

Temperament assessment related to breed groups S.E. Dowd 2006 Assessment of Canine Temperament in Relation to Breed Groups Scot E. Dowd Ph.D. Matrix Canine Research Institute. PO BOX 1332, Shallowater, TX 79363, [email protected] , http://www.canineresearch.org . Abstract Breed specific legislations (BSL), are laws that discriminate against dogs of specific breeds and breed groups. BSL similar to human racial profiling is based upon the premise that certain breed types are more dangerous to humans because of genetic temperament predispositions. The American Pit Bull Terrier and the American Staffordshire Terrier are the breeds most targeted by BSL. In the current study, the temperaments of over 25,000 dogs, of various breeds, have been evaluated including 1136 dogs from the pit bull group and 469 American Pit Bull Terriers. Using results of a rigorous pass-fail temperament test, designed to evaluate characteristics such as human aggression, these analyses statistically evaluated the proportion of dogs categorized by breed groups (e.g. sporting, pit bull, hound, toy, terrier) passing. Interestingly, results show that the pit bull group had a significantly higher passing proportion (p < 0.05) than all other pure breed groups, except the Sporting and Terrier groups. These groups however, did not have a statistically higher passing proportion (p = 0.78) than the pit bull group. This study has provided data to indicate the classification of dog breed groups with respect to their inherent temperament, as part of BSL, may lack scientific credibility. Breed stereotyping, like racial profiling, ignores the complex environmental factors that contribute to canine temperament and behavior.