Powerless in Movement: How Social Movements Influence, and Fail to Influence, American Oliticsp and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Yarns and Funny Jokes

f IMfWtMTYLIBRARY^)Of AUKJUNIA h SAMMMO ^^F -J) NEW YARNS AND COMPRISING ORIGINAL AND SELECTED MERIGAN * HUMOR WITH MANY LAUGHABLE ILLUSTRATIONS. Copyright, 1890, by EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE. NEW YORK* EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSB, 29 & 3 1 Beekman Street EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE, 29 &. 31 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. PAYNE'S BUSINESS EDUCATOR AN- ED cyclopedia of the Knowl* edge necessary to the Conduct of Business, AMONG THE CONTENTS ARE: An Epitome of the Laws of the various States of the Union, alphabet- ically arranged for ready reference ; Model Business Letters and Answers ; in Lessons Penmanship ; Interest Tables ; Rules of Order for Deliberative As- semblies and Debating Societies Tables of Weights and Measures, Stand- ard and the Metric System ; lessons in Typewriting; Legal Forms for all Instruments used in Ordinary Business, such as Leases, Assignments, Contracts, etc., etc.; Dictionary of Mercantile Terms; Interest Laws of the United States; Official, Military, Scholastic, Naval, and Professional Titles used in U. S.; How to Measure Land ; in Yalue of Foreign Gold and Silver Coins the United states ; Educational Statistics of the World ; List of Abbreviations ; and Italian and Phrases Latin, French, Spanish, Words -, Rules of Punctuation ; Marks of Accent; Dictionary of Synonyms; Copyright Law of the United States, etc., etc., MAKING IN ALL THE MOST COMPLETE SELF-EDUCATOR PUBLISHED, CONTAINING 600 PAGES, BOUND IN EXTRA CLOTH. PRICE $2.00. N.B.- LIBERAL TERMS TO AGENTS ON THIS WORK. The above Book sent postpaid on receipt of price. Yar]Qs Jokes. ' ' A Natural Mistake. Well, Jim was champion quoit-thrower in them days, He's dead now, poor fellow, but Jim was a boss on throwing quoits. -

Kickstart Your Social Media Marketing

Social Media 101 Your Anti-Sales Social Media Action Plan Text Copyright © STARTUP UNIVERSITY All Rights Reserved No part of this document or the related files may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, by any means (electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. LEAsectionR 1 N The Basics to Get Started What Social Media Isn’t Sorry to break it to you but here’s a few things that social media was never, ever designed for: 1. Free marketing Do you really thing Mark Zuckerberg became a billionaire by giving away free advertising? Social media is a branding tool – not a marketing tool. It’s designed to give the public a taste of your business, get to know you a little bit, and let them know how to find out more information – if they want to! 2. One-way conversations Social media is a two+ mostly public conversation. The user has the power to click away, so why would they ever watch or read advertising they were not interested in? 3. Soap-box speeches Again, it’s a conversation, not a pulpit. 4. Non-judgmental comments Tweet an unpopular, misleading, or misguided message and prepare the face the wrath of…everyone on the planet. 5. Easy money Actually, using social media is very easy. It’s just not easy for businesses. This cheat sheet will help you figure out how you want to use social media, and help you avoid the biggest blunders. Your Social Media Goals 1. Build your brand’s image 2. -

Structures in the Mind: Chap18

© 2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or informa- tion storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected]. edu. This book was set in Times by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Structures in the mind : essays on language, music, and cognition in honor of Ray Jackendoff / edited by Ida Toivonen, Piroska Csúri, and Emile van der Zee. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-02942-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Psycholinguistics. 2. Cognitive science. 3. Neurolinguistics. 4. Cognition. I. Jackendoff, Ray, 1945- honoree. II. Toivonen, Ida. III. Csúri, Piroska. IV. Zee, Emile van der. P37.S846 2015 401 ′ .9–dc23 2015009287 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 18 The Friar’s Fringe of Consciousness Daniel Dennett Ray Jackendoff’s Consciousness and the Computational Mind (1987) was decades ahead of its time, even for his friends. Nick Humphrey, Marcel Kinsbourne, and I formed with Ray a group of four disparate thinkers about consciousness back around 1986, and, usually meeting at Ray’s house, we did our best to understand each other and help each other clarify the various difficult ideas we were trying to pin down. Ray’s book was one of our first topics, and while it definitely advanced our thinking on various lines, I now have to admit that we didn’t see the importance of much that was expressed therein. -

Classics in Jazz

1 Classics in Jazz Introduction - 2 First Jazz Recording - 5 The Influence of Jazz in Europe and the World - 70 Harling - A Light From St. Agnus - 205 2 Jazz’s Use of Classical Material Introduction Jazz, through its history, has progressed past a number of evolutions; it has had its influences and had both a musical and social background. History never begins or stops at a definite time, nor is it developed by one individual. Growth happens by various situations and experimentation and by creative people. Jazz is a style and not a form. Styles develop and forms are created. Thus jazz begins when East meets West. Jazz evolved in the U.S. with the environment of the late 19th and early 20th century; the music system of Europe, and Africa (with influence of Arab music with the rhythms of the native African. The brilliant book “Post & Branches of Jazz” by Dr. Lloyd C. Miller describes the musical cultures that brought their styles that combined to produce jazz. The art of jazz is over 100 years old now and we have the gift of time to examine the past and by careful research and thought we can produce more accurate conclusions of jazz’s past influences. Jazz could not have developed anywhere but the U.S. In his article” Jazz – The National Anthem” by Frank Patterson in the May 4th, 1922 Musical Courier we read: “Is it Americanism? Well, that is a fine point of contention. There are those who say it is not, that it expresses nothing of the American character; that it is exotic, African Oriental, what not. -

Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Capano, Fabio, "Between the Local and the National: The Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianita," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 5312. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/5312 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between the Local and the National: the Free Territory of Trieste, "Italianità," and the Politics of Identity from the Second World War to the Osimo Treaty Fabio Capano Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Modern Europe Joshua Arthurs, Ph.D., Co-Chair Robert Blobaum, Ph.D., Co-Chair Katherine Aaslestad, Ph.D. -

The Infirmity of Social Democracy in Postcommunist Poland a Cultural History of the Socialist Discourse, 1970-1991

The Infirmity of Social Democracy in Postcommunist Poland A cultural history of the socialist discourse, 1970-1991 by Jan Kubik Assistant Professor of Political Science, Rutgers University American Society of Learned Societies Fellow, 1990-91 Program on Central and Eastem Europe Working Paper Series #20 January 1992 2 The relative weakness of social democracy in postcommunist Eastern Europe and the poor showing of social democratic parties in the 1990-91 Polish and Hungarian elections are intriguing phenom ena. In countries where economic reforms have resulted in increasing poverty, job loss, and nagging insecurity, it could be expected that social democrats would have a considerable follOwing. Also, the presence of relatively large working class populations and a tradition of left-inclined intellec tual opposition movements would suggest that the social democratic option should be popular. Yet, in the March-April 1990 Hungarian parliamentary elections, "the political forces ready to use the 'socialist' or the 'social democratic' label in the elections received less than 16 percent of the popular vote, although the class-analytic approach predicted that at least 20-30 percent of the working population ... could have voted for them" (Szelenyi and Szelenyi 1992:120). Simi larly, in the October 1991 Polish parliamentary elections, the Democratic Left Alliance (an elec toral coalition of reformed communists) received almost 12% of the vote. Social democratic parties (explicitly using this label) that emerged from Solidarity won less than 3% of the popular vote. The Szelenyis concluded in their study of social democracy in postcommunist Hungary that, "the major opposition parties all posited themselves on the political Right (in the Western sense of the term), but public opinion was overwhelmingly in favor of social democratic measures" (1992:125). -

View Full Issue As

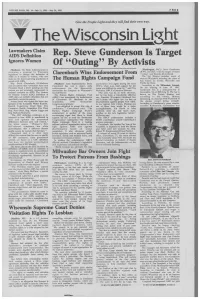

VOLUME FOUR, NO. 14—July 11, 1991—July 24, 1991 FREE Give the People Light and they will find their own way. The Wisconsin Light Lawmakers Claim AIDS Definition Rep. Steve Gunderson Is Target Ignores Women Of "Outing" By Activists [Madison]- The Bush Administration is [Washington, D.C.]- Steve Gunderson reviewing a proposal by Wisconsin (R-WI, 3rd Dist.) was the target of heavy legislators to change the definition of Clarenbach Wins Endorsement From "outing" over the July 4th weekend. AIDS as it relates to women, who now The 3rd District includes much of make up the fastest-growing population of The Human Rights Campaign Fund western Wisconsin including the cities of people with AIDS. Eau Claire, La Crosse, Platteville and Rep. David Clarenbach (D-Madison) [Madison]. State Representative David and Lesbian civil rights during the early Prairie du Chien. and seventeen other lawmakers have sent Clarenbach has won a major, early 1970's, when even mild support for the According to the Milwaukee Journal, President Bush a letter pointing out that endorsement for the Democratic cause was difficult to come by," said Tim On the evening of June 30, 1991, woman are not accurately represented in nomination for Congress in Wisconsin's McFeeley, HRCF's Executive Director. Gunderson was in a restaurant/bar in national statistics on AIDS. The Centers Second District. "Not only was he an early advocate, Alexandria, VA at 808 King St. The bar is for Disease Control (CDC) definition of The Human Rights Campaign Fund but he has been a remarkable effective known as The French Quarter and AIDS does not include infections that are (HRCF) has announced its endorsement one. -

The Gay Revolution: the Story of the Struggle PDF Book

THE GAY REVOLUTION: THE STORY OF THE STRUGGLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Lillian Faderman | 798 pages | 22 Oct 2015 | SIMON & SCHUSTER | 9781451694116 | English | New York, United States The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle PDF Book The days of rage become years of struggle. In general, Faderman only pays periodic lip service to trans-led movements in the same cursory way she only pays lip service to radical movements altogether. I know from my own perspective as a life-long lesbian activist, it was my finding these organizations as a teenager that led me to my own activism. But, in a stunning disconnect, lawmakers and the medical doctors who influenced them preferred to insist that people who engaged in such acts comprised a tiny distinct group, different from the rest of humanity. The inspiring history told in this book testifies to the truth of Margaret Mead's famous words: 'Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. We need to be mad. In her prologue, Faderman starts with Johnson and ends with the ceremony to bestow the rank of brigadier general two stars to Army Colonel Tammy Smith. Family Values. It treats so many of the important, but lesser-known moments in this history and brings to life the many players that have made the movement successful as well as highlighting some of the failures in instructive ways. Anisfield- Wolf Book Award. While the history was fascinating, by the time I got near the end I was missing a sense of what it was actually like to live as a gay person in each of the eras she described. -

Social Movements: Iberian Connections

ARTICLE Copyright © 2009 SAGE Publications (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore and Washington DC) Young www.sagepublications.com Vol 17(4): 421–442 Nordic Journal of Youth Research 10.1177/110330880901700405 Global citizenship and the ‘New, New’ social movements: Iberian connections CARLES FEIXA University of Lleida, Spain INÊS PEREIRA CIES/ISCTE, Lisbon, Portugal/FCT JEFFREY S. JURIS Northeastern University, USA Abstract The past two decades have witnessed the rise of a new global cycle of collective action not only organized through the Internet and made visible during mass pro- test events, but also locally shaped by diverse organizations, networks, platforms and groups. FocusingNOT on FOR specifi c casesCOMMERCIAL in two Iberian cities — Barcelona USE and Lisbon — we argue that this protest cycle has given rise to new kinds of movements referred to here as ‘new, new’ social movements. We analyze particular aspects of each case, but also discuss their European and global dimensions. The article will also highlight the role of youth, discussing the characteristics associated with the participation of young people in the ‘new, new’ movements. After a short introduction to the research on this topic, focusing on the emergence of the ‘anti-corporate globalization movement’ and related theoretical implications, we provide a description of four protest events in Barcelona and Lisbon. Next, we analyze the local contexts that anchor these events. Finally, we discuss the main 422 Young 17:4 (2009): 421–442 characteristics of the ‘new, new’ social movements, examining the links between Barcelona and Lisbon and the wider international context that shapes them and paying particular attention to contemporary networking dynamics. -

The Apology | the B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero Scene & Heard

November-December 2017 VOL. 32 THE VIDEO REVIEW MAGAZINE FOR LIBRARIES N O . 6 IN THIS ISSUE One Week and a Day | Poverty, Inc. | The Apology | The B-Side | Night School | Madonna: Rebel Heart Tour | Betting on Zero scene & heard BAKER & TAYLOR’S SPECIALIZED A/V TEAM OFFERS ALL THE PRODUCTS, SERVICES AND EXPERTISE TO FULFILL YOUR LIBRARY PATRONS’ NEEDS. Learn more about Baker & Taylor’s Scene & Heard team: ELITE Helpful personnel focused exclusively on A/V products and customized services to meet continued patron demand PROFICIENT Qualified entertainment content buyers ensure frontlist and backlist titles are available and delivered on time SKILLED Supportive Sales Representatives with an average of 15 years industry experience DEVOTED Nationwide team of A/V processing staff ready to prepare your movie and music products to your shelf-ready specifications Experience KNOWLEDGEABLE Baker & Taylor is the Full-time staff of A/V catalogers, most experienced in the backed by their MLS degree and more than 43 years of media cataloging business; selling A/V expertise products to libraries since 1986. 800-775-2600 x2050 [email protected] www.baker-taylor.com Spotlight Review One Week and a Day and target houses that are likely to be empty while mourners are out. Eyal also goes to the HHH1/2 hospice where Ronnie died (and retrieves his Oscilloscope, 98 min., in Hebrew w/English son’s medical marijuana, prompting a later subtitles, not rated, DVD: scene in which he struggles to roll a joint for Publisher/Editor: Randy Pitman $34.99, Blu-ray: $39.99 the first time in his life), gets into a conflict Associate Editor: Jazza Williams-Wood Wr i t e r- d i r e c t o r with a taxi driver, and tries (unsuccessfully) to hide in the bushes when his neighbors show Editorial Assistant: Christopher Pitman Asaph Polonsky’s One Week and a Day is a up with a salad. -

The Commune Movement During the 1960S and the 1970S in Britain, Denmark and The

The Commune Movement during the 1960s and the 1970s in Britain, Denmark and the United States Sangdon Lee Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of History September 2016 i The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement ⓒ 2016 The University of Leeds and Sangdon Lee The right of Sangdon Lee to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ii Abstract The communal revival that began in the mid-1960s developed into a new mode of activism, ‘communal activism’ or the ‘commune movement’, forming its own politics, lifestyle and ideology. Communal activism spread and flourished until the mid-1970s in many parts of the world. To analyse this global phenomenon, this thesis explores the similarities and differences between the commune movements of Denmark, UK and the US. By examining the motivations for the communal revival, links with 1960s radicalism, communes’ praxis and outward-facing activities, and the crisis within the commune movement and responses to it, this thesis places communal activism within the context of wider social movements for social change. Challenging existing interpretations which have understood the communal revival as an alternative living experiment to the nuclear family, or as a smaller part of the counter-culture, this thesis argues that the commune participants created varied and new experiments for a total revolution against the prevailing social order and its dominant values and institutions, including the patriarchal family and capitalism. -

Fringe Season 1 Transcripts

PROLOGUE Flight 627 - A Contagious Event (Glatterflug Airlines Flight 627 is enroute from Hamburg, Germany to Boston, Massachusetts) ANNOUNCEMENT: ... ist eingeschaltet. Befestigen sie bitte ihre Sicherheitsgürtel. ANNOUNCEMENT: The Captain has turned on the fasten seat-belts sign. Please make sure your seatbelts are securely fastened. GERMAN WOMAN: Ich möchte sehen wie der Film weitergeht. (I would like to see the film continue) MAN FROM DENVER: I don't speak German. I'm from Denver. GERMAN WOMAN: Dies ist mein erster Flug. (this is my first flight) MAN FROM DENVER: I'm from Denver. ANNOUNCEMENT: Wir durchfliegen jetzt starke Turbulenzen. Nehmen sie bitte ihre Plätze ein. (we are flying through strong turbulence. please return to your seats) INDIAN MAN: Hey, friend. It's just an electrical storm. MORGAN STEIG: I understand. INDIAN MAN: Here. Gum? MORGAN STEIG: No, thank you. FLIGHT ATTENDANT: Mein Herr, sie müssen sich hinsetzen! (sir, you must sit down) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Beruhigen sie sich! (calm down!) Entschuldigen sie bitte! Gehen sie zu ihrem Sitz zurück! [please, go back to your seat!] FLIGHT ATTENDANT: (on phone) Kapitän! Wir haben eine Notsituation! (Captain, we have a difficult situation!) PILOT: ... gibt eine Not-... (... if necessary...) Sprechen sie mit mir! (talk to me) Was zum Teufel passiert! (what the hell is going on?) Beruhigen ... (...calm down...) Warum antworten sie mir nicht! (why don't you answer me?) Reden sie mit mir! (talk to me) ACT I Turnpike Motel - A Romantic Interlude OLIVIA: Oh my god! JOHN: What? OLIVIA: This bed is loud. JOHN: You think? OLIVIA: We can't keep doing this.