(Cellvizio) Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy in Gastroenterology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gastrointestinal Cancers a Multidisciplinary Approach to Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Second Annual Update on Gastrointestinal Cancers A Multidisciplinary Approach to Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Friday, September 27, 2013 7:00am – 4:10pm COURSE DIRECTORS K.S. Clifford Chao, MD Michel Kahaleh, MD, AGAF, FACG, FASGE P. Ravi Kiran, MBBS, MS, FRCS, FACS Tyvin Rich, MD, FACR LOCATION Columbia University Medical Center Bard Hall New York City Register Online www.columbiasurgerycme.org Second Annual Update on Gastrointestinal Cancers A Multidisciplinary Approach to Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment OVERVIEW EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES This course consists of lectures, case It is intended that this Continuing presentations, and Q&A panels with Medical Education (CME) activity will lead expert faculty. The course is broken into to improved patient care. At the conclusion five sessions, each covering gastrointestinal of this activity, participants should be able to: cancer in a specific area of the GI tract. 1. Identify new technologies and modalities Speakers in each session will cover research in the screening, surveillance, and diagnosis and the latest standards of care including of relevant gastrointestinal cancers. new innovations for screening, diagnosis, and treatment modalities including radiation 2. Offer patients non-invasive, interventional, therapy, chemotherapy, and surgery. This medical, and surgical approaches in the course will increase participant familiariza- treatment of gastrointestinal cancers. tion with current guidelines and recommen- 3. Identify emerging new chemotherapy, dations, and focus on the multidisciplinary targeted therapy, and radiation therapy team involved in the care of patients with options and approaches in the treatment gastrointestinal cancers. of gastrointestinal cancers. IDENTIFIED PRACTICE GAP/ 4. Apply their enhanced understanding of EDUCATIONAL NEEDS the benefits of the multidisciplinary approach to the screening, diagnosis, Gastrointestinal cancers include several treatment, and palliation of patients with malignancies, including those of the gastrointestinal cancers. -

Practice Patterns and Use of Endoscopic Retrograde

Practice patterns and use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the management of recurrent acute pancreatitis Qiang Cai, Emory University Field Willingham, Emory University Steven Keilin, Emory University Vaishali Patel, Emory University Parit Mekaroonkamol, Emory University JB Reichstein, Duke University S Dacha, Emory University Journal Title: Clinical Endoscopy Volume: Volume 53, Number 1 Publisher: (publisher) | 2019-01-01, Pages 73-81 Type of Work: Article Publisher DOI: 10.5946/ce.2019.052 Permanent URL: https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/vhjfb Final published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.5946/ce.2019.052 Accessed September 27, 2021 7:02 AM EDT ORIGINAL ARTICLE Clin Endosc 2020;53:73-81 https://doi.org/10.5946/ce.2019.052 Print ISSN 2234-2400 • On-line ISSN 2234-2443 Open Access Practice Patterns and Use of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in the Management of Recurrent Acute Pancreatitis Jonathan B. Reichstein1, Vaishali Patel2, Parit Mekaroonkamol2, Sunil Dacha2, Steven A. Keilin2, Qiang Cai2 and Field F. Willingham2 1Department of Medicine, Duke University, Durham, NC, 2Division of Digestive Disease, Department of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA Background/Aims: There are conflicting opinions regarding the management of recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP). While some physicians recommend endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in this setting, others consider it to be contraindicated in patients with RAP. The aim of this study was to assess the practice patterns and clinical features influencing the management of RAP in the US. Methods: An anonymous 35-question survey instrument was developed and refined through multiple iterations, and its use was approved by our Institutional Review Board. -

Colorectal Cancer Screening

CLINICAL MEDICAL POLICY Policy Name: Colorectal Cancer Screening Policy Number: MP-059-MD-PA Responsible Department(s): Medical Management Provider Notice Date: 03/19/2021 Issue Date: 03/19/2021 Effective Date: 04/19/2021 Next Annual Review: 02/2022 Revision Date: 02/17/2021 Products: Gateway Health℠ Medicaid Application: All participating hospitals and providers Page Number(s): 1 of 10 DISCLAIMER Gateway Health℠ (Gateway) medical policy is intended to serve only as a general reference resource regarding coverage for the services described. This policy does not constitute medical advice and is not intended to govern or otherwise influence medical decisions. POLICY STATEMENT Gateway Health℠ may provide coverage under the medical-surgical benefits of the Company’s Medicaid products for medically necessary colorectal cancer screening procedures. This policy is designed to address medical necessity guidelines that are appropriate for the majority of individuals with a particular disease, illness or condition. Each person’s unique clinical circumstances warrant individual consideration, based upon review of applicable medical records. (Current applicable Pennsylvania HealthChoices Agreement Section V. Program Requirements, B. Prior Authorization of Services, 1. General Prior Authorization Requirements.) Policy No. MP-059-MD-PA Page 1 of 10 DEFINITIONS Average-Risk Population – Patient population defined as having no personal history of adenomatous polyps, colorectal cancer, or inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative Colitis); no family history of colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps, familial adenomatous polyposis, or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. High-Risk Population – Patient population defined as having a first-degree relative (sibling, parent, or child) who has had colorectal cancer or adenomatous polyps; OR family history of familial adenomatous polyposis; OR family history of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer; OR family history of MYH- associated polyposis in siblings; OR diagnosis of Cowden syndrome. -

Interventional Innovations in Digestive Care to Receive the Negotiated Group Rate

The First Annual Peter D. Stevens Course on Interventional Innovations in Digestive Ca re Special Sessions: Hands-on Animal Tissue Labs, Live OR & Interventional Cases April 2 6–27, 2012 New York City Program Co-Directors: Michel Kahaleh, MD, AGAF, FACG, FASGE Robbyn Sockolow, MD, AGAF Marc Bessler, MD, FACS Jeffrey Milsom, MD, FACS, FACG www.gi-innovations.org Endorsed by This course is endorsed by the American Society for Endorsed by the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy AGA Institute Interventional Innov ations in Digestive Ca re n Overall Goals This two day course will inform participants of the latest innovations for the management of gastrointestinal diseases and disorders, and will offer a unique opportunity to learn more about the current trends in interventional endoscopic and surgical procedures. Internationally recognized faculty will address issues in current clinical practice, compli - cations and pitfalls of newer technologies, and the evolution of the field. Using a systems- based approach, the format will cover all major areas of digestive care and treatment options. Attendee participation and interaction will be emphasized and facilitated through Q & A sessions, live OR and interactive case presentations, hands-on animal tissue labs and meet the professor break-out sessions. n Learning Objectives • Understand endoscopic necrosectomy • Understand the use of ablation • Increase knowledge of the latest therapy for bile duct cancer innovations in minimally invasive • Learn the latest advances in techniques in bariatrics endoscopic -

Endoscopic Ultrasound

CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY Series Editor George Y. Wu University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT, USA For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/7672 Endoscopic Ultrasound Edited by VANESSA M. SHA M I , MD Director of Endoscopic Ultrasound University of Virginia Health System Digestive Health Center, USA and MICHEL KAHALEH , MD Director of Pancreatico-Biliary Services University of Virginia Health System Digestive Health Center, USA Editors Vanessa M. Shami, MD Michel Kahaleh, MD Associate Professor of Medicine Associate Professor of Medicine Director of Endoscopic Ultrasound Director of Pancreatico-Biliary Services Digestive Health Center Digestive Health Center University of Virginia Health System University of Virginia Health System Charlottesville, VA, USA Charlottesville, USA [email protected] [email protected] ISBN 978-1-60327-479-1 e-ISBN 978-1-60327-480-7 DOI 10.1007/978-1-60327-480-7 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2010930043 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Humana Press, c/o Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. -

Geisinger Lewistown Hospital Published: March 25, 2019

Geisinger Lewistown Hospital Published: March 25, 2019 DESCRIPTION CHARGE Fine needle aspiration; without imaging guidance $ 607.00 Fine needle aspiration; without imaging guidance $ 286.00 Fine needle aspiration; with imaging guidance $ 2,218.00 Fine needle aspiration; with imaging guidance $ 1,691.00 Placement of soft tissue localization device(s) (eg, clip, metallic pellet, wire/needle, radioactive seeds), percutaneous, including imaging guidance; first lesion $ 1,979.00 Placement of soft tissue localization device(s) (eg, clip, metallic pellet, wire/needle, radioactive seeds), percutaneous, including imaging guidance; each $ 1,385.00 additional lesion (List separately in addition to code for primary procedure) Incision and drainage of abscess (eg, carbuncle, suppurative hidradenitis, cutaneous or subcutaneous abscess, cyst, furuncle, or paronychia); simple or single $ 657.00 Incision and drainage of abscess (eg, carbuncle, suppurative hidradenitis, cutaneous or subcutaneous abscess, cyst, furuncle, or paronychia); complicated or $ 986.00 multiple Incision and drainage of pilonidal cyst; simple $ 657.00 Incision and drainage of pilonidal cyst; complicated $ 3,726.00 Incision and removal of foreign body, subcutaneous tissues; simple $ 1,694.00 Incision and removal of foreign body, subcutaneous tissues; complicated $ 4,710.00 Incision and drainage of hematoma, seroma or fluid collection $ 3,470.00 Puncture aspiration of abscess, hematoma, bulla, or cyst $ 1,272.00 Puncture aspiration of abscess, hematoma, bulla, or cyst $ 657.00 Incision -

Stents for the Gastrointestinal Tract and Nutritional Implications

NUTRITION ISSUES IN GASTROENTEROLOGY, SERIES #46 Carol Rees Parrish, R.D., M.S., Series Editor Stents for the Gastrointestinal Tract and Nutritional Implications Michelle Loch Michel Kahaleh Endoscopic stenting of many sites along the gastrointestinal tract is used successfully for palliation of malignant or benign obstructions. These obstructions may be the result of primary gastrointestinal tumors invading the lumen, tumors of another primary site causing external compression or in some instance benign diseases secondary to various inflammatory processes. Stenting of the gastrointestinal tract has been commonly per- formed either by interventional radiologists with the use of fluoroscopy, or by gas- troenterologists endoscopically, with or without fluoroscopic guidance. Their efficacy can be measured by resolution of obstruction or symptom improvement. The current literature shows that endoscopic stenting have acceptable success and complication rates and might be considered as first-line therapy in centers offering expertise in inter- ventional endoscopy. The techniques, efficacy and complication of stenting will be dis- cussed. Nutritional guidelines will also be provided based on our institutions practice. INTRODUCTION most current literature (Table 1) (4–9). Common causes ndoscopy within the last two decades has encom- of stent requirement to preserve nutritional status passed many interventional procedures allowing include esophageal, duodenal, biliary and colonic Ethe treatment of multiple conditions of the upper obstruction; -

Confocal Laser Microscopy in Neurosurgery: State of the Art of Actual Clinical Applications

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Confocal Laser Microscopy in Neurosurgery: State of the Art of Actual Clinical Applications Francesco Restelli 1, Bianca Pollo 2 , Ignazio Gaspare Vetrano 1 , Samuele Cabras 1, Morgan Broggi 1 , Marco Schiariti 1, Jacopo Falco 1, Camilla de Laurentis 1, Gabriella Raccuia 1, Paolo Ferroli 1 and Francesco Acerbi 1,* 1 Department of Neurosurgery, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (F.R.); [email protected] (I.G.V.); [email protected] (S.C.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (M.S.); [email protected] (J.F.); [email protected] (C.d.L.); [email protected] (G.R.); [email protected] (P.F.) 2 Neuropathology Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, 20133 Milan, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-022-3932-309 Abstract: Achievement of complete resections is of utmost importance in brain tumor surgery, due to the established correlation among extent of resection and postoperative survival. Various tools have recently been included in current clinical practice aiming to more complete resections, such as neuronavigation and fluorescent-aided techniques, histopathological analysis still remains the gold-standard for diagnosis, with frozen section as the most used, rapid and precise intraoperative histopathological method that permits an intraoperative differential diagnosis. Unfortunately, due Citation: Restelli, F.; Pollo, B.; to the various limitations linked to this technique, it is still unsatisfactorily for obtaining real-time Vetrano, I.G.; Cabras, S.; Broggi, M.; intraoperative diagnosis. -

Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopy of Biliary Diseases

DISEASES OF THE BILIARY TRACT, SERIES #6 Rad Agrawal, M.D., Series Editor Diagnostic and Therapeutic Endoscopy of Biliary Diseases by Yamini Subbiah, Shyam Thakkar, Elie Aoun The therapeutic approach to biliary diseases has undergone a paradigm shift over the past decade toward minimally invasive endoscopic interventions. This paper reviews the advances and different diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic approaches to common biliary diseases including choledocholithiasis, benign and malignant biliary strictures and bile leaks. INTRODUCTION endoscopist to differentiate between benign and malig- ith the introduction of innovative endoscopic nant features, thus guiding decision making in real time. implements and options allowing for unprece- Wdented access to the biliary tree, the therapeutic COMMON BILE DUCT STONES approach to biliary diseases has undergone a significant Over 98% of biliary disorders are linked to gallstones. paradigm shift over the past decade toward minimally Stones are found in the common bile duct (CBD) in up invasive endoscopic interventions. The days where bil- to 18% of patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis (1). iary diseases were exclusively managed surgically are The vast majority of gallstones are cholesterol-rich, long gone, and much has changed since the first form in the gallbladder and gain access to the CBD via reported biliary sphincterotomies in 1974. The recent the cystic duct. De novo CBD stone formation is also developments in peroral cholangioscopy and new well described and is more common in patients of modalities of anchoring high resolution nasogastric Asian descent. These primary duct stones typically scopes in the bile duct offer the opportunity of direct have a higher bilirubin and a lower cholesterol content visualization of the bile duct lumen, which allows for and biliary stasis; further, bacterial infections have not only better identification of the underlying disease been implicated in their pathogenesis (2,3). -

Confocal Laser Endomicroscopy Platform Large Addressable Market: Early Cancer Diagnosis in GI, Urology, Interventional 2 Pulmonology, Others

Mauna Kea Technologies Corporate Presentation - November 2018 Disclaimer • This document has been prepared by Mauna Kea Technologies (the "Company") and is provided for information purposes only. • The information and opinions contained in this document speak only as of the date of this document and may be updated, supplemented, revised, verified or amended, and such information may be subject to significant changes. Mauna Kea Technologies is not under any obligation to update the information contained herein and any opinion expressed in this document is subject to change without prior notice. • The information contained in this document has not been independently verified. No representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, completeness or appropriateness of the information and opinions contained in this document. The Company, its subsidiary, its advisors and representatives accept no responsibility for and shall not be held liable for any loss or damage that may arise from the use of this document or the information or opinions contained herein. • This document contains information on the Company’s markets and competitive position, and more specifically, on the size of its markets. This information has been drawn from various sources or from the Company’s own estimates. Investors should not base their investment decision on this information. • This document contains certain forward-looking statements. These statements are not guarantees of the Company's future performance. These forward- looking statements relate to the Company's future prospects, developments and marketing strategy and are based on analyses of earnings forecasts and estimates of amounts not yet determinable. Forward-looking statements are subject to a variety of risks and uncertainties as they relate to future events and are dependent on circumstances that may or may not materialize in the future. -

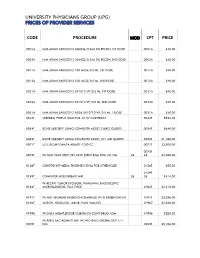

Code Procedure Cpt Price University Physicians Group

UNIVERSITY PHYSICIANS GROUP (UPG) PRICES OF PROVIDER SERVICES CODE PROCEDURE MOD CPT PRICE 0001A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 1ST DOSE 0001A $40.00 0002A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 30MCG/0.3ML DIL RECON 2ND DOSE 0002A $40.00 0011A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0011A $40.00 0012A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 100 MCG/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0012A $40.00 0021A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 1ST DOSE 0021A $40.00 0022A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 5X1010 VP/0.5 ML 2ND DOSE 0022A $40.00 0031A IMM ADMN SARSCOV2 AD26 5X10^10 VP/0.5 ML 1 DOSE 0031A $40.00 0042T CEREBRAL PERFUS ANALYSIS, CT W/CONTRAST 0042T $954.00 0054T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, FLURO GUIDED 0054T $640.00 0055T BONE SURGERY USING COMPUTER ASSIST, CT/ MRI GUIDED 0055T $1,188.00 0071T U/S LEIOMYOMATA ABLATE <200 CC 0071T $2,500.00 0075T 0075T PR TCAT PLMT XTRC VRT CRTD STENT RS&I PRQ 1ST VSL 26 26 $2,208.00 0126T CAROTID INT-MEDIA THICKNESS EVAL FOR ATHERSCLER 0126T $55.00 0159T 0159T COMPUTER AIDED BREAST MRI 26 26 $314.00 PR RECTAL TUMOR EXCISION, TRANSANAL ENDOSCOPIC 0184T MICROSURGICAL, FULL THICK 0184T $2,315.00 0191T PR ANT SEGMENT INSERTION DRAINAGE W/O RESERVOIR INT 0191T $2,396.00 01967 ANESTH, NEURAXIAL LABOR, PLAN VAG DEL 01967 $2,500.00 01996 PR DAILY MGMT,EPIDUR/SUBARACH CONT DRUG ADM 01996 $285.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ UNI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 1/> 0200T NDL 0200T $5,106.00 PR PERQ SAC AGMNTJ BI W/WO BALO/MCHNL DEV 2/> 0201T NDLS 0201T $9,446.00 PR INJECT PLATELET RICH PLASMA W/IMG 0232T HARVEST/PREPARATOIN 0232T $1,509.00 0234T PR TRANSLUMINAL PERIPHERAL ATHERECTOMY, RENAL -

Cycloid Scanning for Wide Field Optical Coherence Tomography Endomicroscopy and Angiography in Vivo

Cycloid scanning for wide field optical coherence tomography endomicroscopy and angiography in vivo The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Liang, Kaicheng et al. "Cycloid scanning for wide field optical coherence tomography endomicroscopy and angiography in vivo." Optica 5, 1 (January 2018): 36-43 © 2018 Optical Society of America As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OPTICA.5.000036 Publisher OSA Publishing Version Author's final manuscript Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/121433 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Optica. Manuscript Author Author manuscript; Manuscript Author available in PMC 2018 April 20. Published in final edited form as: Optica. 2018 January 20; 5(1): 36–43. doi:10.1364/OPTICA.5.000036. Cycloid scanning for wide field optical coherence tomography endomicroscopy and angiography in vivo Kaicheng Liang1,†, Zhao Wang1,†, Osman O. Ahsen1, Hsiang-Chieh Lee1, Benjamin M. Potsaid1,2, Vijaysekhar Jayaraman3, Alex Cable2, Hiroshi Mashimo4,5, Xingde Li6, and James G. Fujimoto1,* 1Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, Research Laboratory of Electronics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA 2Thorlabs, Newton, New Jersey 07860, USA 3Praevium Research, Santa Barbara, California 93111, USA 4Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts 02130, USA 5Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA 6Department of Biomedical Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218, USA Abstract Devices that perform wide field-of-view (FOV) precision optical scanning are important for endoscopic assessment and diagnosis of luminal organ disease such as in gastroenterology.