Programming with Hyper-Threading† Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computer Science 246 Computer Architecture Spring 2010 Harvard University

Computer Science 246 Computer Architecture Spring 2010 Harvard University Instructor: Prof. David Brooks [email protected] Dynamic Branch Prediction, Speculation, and Multiple Issue Computer Science 246 David Brooks Lecture Outline • Tomasulo’s Algorithm Review (3.1-3.3) • Pointer-Based Renaming (MIPS R10000) • Dynamic Branch Prediction (3.4) • Other Front-end Optimizations (3.5) – Branch Target Buffers/Return Address Stack Computer Science 246 David Brooks Tomasulo Review • Reservation Stations – Distribute RAW hazard detection – Renaming eliminates WAW hazards – Buffering values in Reservation Stations removes WARs – Tag match in CDB requires many associative compares • Common Data Bus – Achilles heal of Tomasulo – Multiple writebacks (multiple CDBs) expensive • Load/Store reordering – Load address compared with store address in store buffer Computer Science 246 David Brooks Tomasulo Organization From Mem FP Op FP Registers Queue Load Buffers Load1 Load2 Load3 Load4 Load5 Store Load6 Buffers Add1 Add2 Mult1 Add3 Mult2 Reservation To Mem Stations FP adders FP multipliers Common Data Bus (CDB) Tomasulo Review 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 LD F0, 0(R1) Iss M1 M2 M3 M4 M5 M6 M7 M8 Wb MUL F4, F0, F2 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Ex Ex Ex Ex Wb SD 0(R1), F0 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss M1 M2 M3 Wb SUBI R1, R1, 8 Iss Ex Wb BNEZ R1, Loop Iss Ex Wb LD F0, 0(R1) Iss Iss Iss Iss M Wb MUL F4, F0, F2 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Ex Ex Ex Ex Wb SD 0(R1), F0 Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss Iss M1 M2 -

PIPELINING and ASSOCIATED TIMING ISSUES Introduction: While

PIPELINING AND ASSOCIATED TIMING ISSUES Introduction: While studying sequential circuits, we studied about Latches and Flip Flops. While Latches formed the heart of a Flip Flop, we have explored the use of Flip Flops in applications like counters, shift registers, sequence detectors, sequence generators and design of Finite State machines. Another important application of latches and flip flops is in pipelining combinational/algebraic operation. To understand what is pipelining consider the following example. Let us take a simple calculation which has three operations to be performed viz. 1. add a and b to get (a+b), 2. get magnitude of (a+b) and 3. evaluate log |(a + b)|. Each operation would consume a finite period of time. Let us assume that each operation consumes 40 nsec., 35 nsec. and 60 nsec. respectively. The process can be represented pictorially as in Fig. 1. Consider a situation when we need to carry this out for a set of 100 such pairs. In a normal course when we do it one by one it would take a total of 100 * 135 = 13,500 nsec. We can however reduce this time by the realization that the whole process is a sequential process. Let the values to be evaluated be a1 to a100 and the corresponding values to be added be b1 to b100. Since the operations are sequential, we can first evaluate (a1 + b1) while the value |(a1 + b1)| is being evaluated the unit evaluating the sum is dormant and we can use it to evaluate (a2 + b2) giving us both |(a1 + b1)| and (a2 + b2) at the end of another evaluation period. -

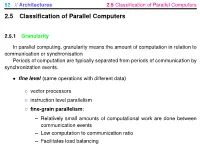

2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers

52 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.1 Granularity In parallel computing, granularity means the amount of computation in relation to communication or synchronisation Periods of computation are typically separated from periods of communication by synchronization events. • fine level (same operations with different data) ◦ vector processors ◦ instruction level parallelism ◦ fine-grain parallelism: – Relatively small amounts of computational work are done between communication events – Low computation to communication ratio – Facilitates load balancing 53 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers – Implies high communication overhead and less opportunity for per- formance enhancement – If granularity is too fine it is possible that the overhead required for communications and synchronization between tasks takes longer than the computation. • operation level (different operations simultaneously) • problem level (independent subtasks) ◦ coarse-grain parallelism: – Relatively large amounts of computational work are done between communication/synchronization events – High computation to communication ratio – Implies more opportunity for performance increase – Harder to load balance efficiently 54 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers 2.5.2 Hardware: Pipelining (was used in supercomputers, e.g. Cray-1) In N elements in pipeline and for 8 element L clock cycles =) for calculation it would take L + N cycles; without pipeline L ∗ N cycles Example of good code for pipelineing: §doi =1 ,k ¤ z ( i ) =x ( i ) +y ( i ) end do ¦ 55 // Architectures 2.5 Classification of Parallel Computers Vector processors, fast vector operations (operations on arrays). Previous example good also for vector processor (vector addition) , but, e.g. recursion – hard to optimise for vector processors Example: IntelMMX – simple vector processor. -

Microprocessor Architecture

EECE416 Microcomputer Fundamentals Microprocessor Architecture Dr. Charles Kim Howard University 1 Computer Architecture Computer System CPU (with PC, Register, SR) + Memory 2 Computer Architecture •ALU (Arithmetic Logic Unit) •Binary Full Adder 3 Microprocessor Bus 4 Architecture by CPU+MEM organization Princeton (or von Neumann) Architecture MEM contains both Instruction and Data Harvard Architecture Data MEM and Instruction MEM Higher Performance Better for DSP Higher MEM Bandwidth 5 Princeton Architecture 1.Step (A): The address for the instruction to be next executed is applied (Step (B): The controller "decodes" the instruction 3.Step (C): Following completion of the instruction, the controller provides the address, to the memory unit, at which the data result generated by the operation will be stored. 6 Harvard Architecture 7 Internal Memory (“register”) External memory access is Very slow For quicker retrieval and storage Internal registers 8 Architecture by Instructions and their Executions CISC (Complex Instruction Set Computer) Variety of instructions for complex tasks Instructions of varying length RISC (Reduced Instruction Set Computer) Fewer and simpler instructions High performance microprocessors Pipelined instruction execution (several instructions are executed in parallel) 9 CISC Architecture of prior to mid-1980’s IBM390, Motorola 680x0, Intel80x86 Basic Fetch-Execute sequence to support a large number of complex instructions Complex decoding procedures Complex control unit One instruction achieves a complex task 10 -

Instruction Pipelining (1 of 7)

Chapter 5 A Closer Look at Instruction Set Architectures Objectives • Understand the factors involved in instruction set architecture design. • Gain familiarity with memory addressing modes. • Understand the concepts of instruction- level pipelining and its affect upon execution performance. 5.1 Introduction • This chapter builds upon the ideas in Chapter 4. • We present a detailed look at different instruction formats, operand types, and memory access methods. • We will see the interrelation between machine organization and instruction formats. • This leads to a deeper understanding of computer architecture in general. 5.2 Instruction Formats (1 of 31) • Instruction sets are differentiated by the following: – Number of bits per instruction. – Stack-based or register-based. – Number of explicit operands per instruction. – Operand location. – Types of operations. – Type and size of operands. 5.2 Instruction Formats (2 of 31) • Instruction set architectures are measured according to: – Main memory space occupied by a program. – Instruction complexity. – Instruction length (in bits). – Total number of instructions in the instruction set. 5.2 Instruction Formats (3 of 31) • In designing an instruction set, consideration is given to: – Instruction length. • Whether short, long, or variable. – Number of operands. – Number of addressable registers. – Memory organization. • Whether byte- or word addressable. – Addressing modes. • Choose any or all: direct, indirect or indexed. 5.2 Instruction Formats (4 of 31) • Byte ordering, or endianness, is another major architectural consideration. • If we have a two-byte integer, the integer may be stored so that the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte or vice versa. – In little endian machines, the least significant byte is followed by the most significant byte. -

Review of Computer Architecture

Basic Computer Architecture CSCE 496/896: Embedded Systems Witawas Srisa-an Review of Computer Architecture Credit: Most of the slides are made by Prof. Wayne Wolf who is the author of the textbook. I made some modifications to the note for clarity. Assume some background information from CSCE 430 or equivalent von Neumann architecture Memory holds data and instructions. Central processing unit (CPU) fetches instructions from memory. Separate CPU and memory distinguishes programmable computer. CPU registers help out: program counter (PC), instruction register (IR), general- purpose registers, etc. von Neumann Architecture Memory Unit Input CPU Output Unit Control + ALU Unit CPU + memory address 200PC memory data CPU 200 ADD r5,r1,r3 ADD IRr5,r1,r3 Recalling Pipelining Recalling Pipelining What is a potential Problem with von Neumann Architecture? Harvard architecture address data memory data PC CPU address program memory data von Neumann vs. Harvard Harvard can’t use self-modifying code. Harvard allows two simultaneous memory fetches. Most DSPs (e.g Blackfin from ADI) use Harvard architecture for streaming data: greater memory bandwidth. different memory bit depths between instruction and data. more predictable bandwidth. Today’s Processors Harvard or von Neumann? RISC vs. CISC Complex instruction set computer (CISC): many addressing modes; many operations. Reduced instruction set computer (RISC): load/store; pipelinable instructions. Instruction set characteristics Fixed vs. variable length. Addressing modes. Number of operands. Types of operands. Tensilica Xtensa RISC based variable length But not CISC Programming model Programming model: registers visible to the programmer. Some registers are not visible (IR). Multiple implementations Successful architectures have several implementations: varying clock speeds; different bus widths; different cache sizes, associativities, configurations; local memory, etc. -

OS and Compiler Considerations in the Design of the IA-64 Architecture

OS and Compiler Considerations in the Design of the IA-64 Architecture Rumi Zahir (Intel Corporation) Dale Morris, Jonathan Ross (Hewlett-Packard Company) Drew Hess (Lucasfilm Ltd.) This is an electronic reproduction of “OS and Compiler Considerations in the Design of the IA-64 Architecture” originally published in ASPLOS-IX (the Ninth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems) held in Cambridge, MA in November 2000. Copyright © A.C.M. 2000 1-58113-317-0/00/0011...$5.00 Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full cita- tion on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers, or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permis- sion and/or a fee. Request permissions from Publications Dept, ACM Inc., fax +1 (212) 869-0481, or [email protected]. ASPLOS 2000 Cambridge, MA Nov. 12-15 , 2000 212 OS and Compiler Considerations in the Design of the IA-64 Architecture Rumi Zahir Jonathan Ross Dale Morris Drew Hess Intel Corporation Hewlett-Packard Company Lucas Digital Ltd. 2200 Mission College Blvd. 19447 Pruneridge Ave. P.O. Box 2459 Santa Clara, CA 95054 Cupertino, CA 95014 San Rafael, CA 94912 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT system collaborate to deliver higher-performance systems. -

Selective Eager Execution on the Polypath Architecture

Selective Eager Execution on the PolyPath Architecture Artur Klauser, Abhijit Paithankar, Dirk Grunwald [klauser,pvega,grunwald]@cs.colorado.edu University of Colorado, Department of Computer Science Boulder, CO 80309-0430 Abstract average misprediction latency is the sum of the architected latency (pipeline depth) and a variable latency, which depends on data de- Control-flow misprediction penalties are a major impediment pendencies of the branch instruction. The overall cycles lost due to high performance in wide-issue superscalar processors. In this to branch mispredictions are the product of the total number of paper we present Selective Eager Execution (SEE), an execution mispredictions incurred during program execution and the average model to overcome mis-speculation penalties by executing both misprediction latency. Thus, reduction of either component helps paths after diffident branches. We present the micro-architecture decrease performance loss due to control mis-speculation. of the PolyPath processor, which is an extension of an aggressive In this paper we propose Selective Eager Execution (SEE) and superscalar, out-of-order architecture. The PolyPath architecture the PolyPath architecture model, which help to overcome branch uses a novel instruction tagging and register renaming mechanism misprediction latency. SEE recognizes the fact that some branches to execute instructions from multiple paths simultaneously in the are predicted more accurately than others, where it draws from re- same processor pipeline, while retaining maximum resource avail- search in branch confidence estimation [4, 6]. SEE behaves like ability for single-path code sequences. a normal monopath speculative execution architecture for highly Results of our execution-driven, pipeline-level simulations predictable branches; it predicts the most likely successor path of a show that SEE can improve performance by as much as 36% for branch, and evaluates instructions only along this path. -

Igpu: Exception Support and Speculative Execution on Gpus

Appears in the 39th International Symposium on Computer Architecture, 2012 iGPU: Exception Support and Speculative Execution on GPUs Jaikrishnan Menon, Marc de Kruijf, Karthikeyan Sankaralingam Department of Computer Sciences University of Wisconsin-Madison {menon, dekruijf, karu}@cs.wisc.edu Abstract the evolution of traditional CPUs to illuminate why this pro- gression appears natural and imminent. Since the introduction of fully programmable vertex Just as CPU programmers were forced to explicitly man- shader hardware, GPU computing has made tremendous age CPU memories in the days before virtual memory, for advances. Exception support and speculative execution are almost a decade, GPU programmers directly and explicitly the next steps to expand the scope and improve the usabil- managed the GPU memory hierarchy. The recent release ity of GPUs. However, traditional mechanisms to support of NVIDIA’s Fermi architecture and AMD’s Fusion archi- exceptions and speculative execution are highly intrusive to tecture, however, has brought GPUs to an inflection point: GPU hardware design. This paper builds on two related in- both architectures implement a unified address space that sights to provide a unified lightweight mechanism for sup- eliminates the need for explicit memory movement to and porting exceptions and speculation on GPUs. from GPU memory structures. Yet, without demand pag- First, we observe that GPU programs can be broken into ing, something taken for granted in the CPU space, pro- code regions that contain little or no live register state at grammers must still explicitly reason about available mem- their entry point. We then also recognize that it is simple to ory. The drawbacks of exposing physical memory size to generate these regions in such a way that they are idempo- programmers are well known. -

CS152: Computer Systems Architecture Pipelining

CS152: Computer Systems Architecture Pipelining Sang-Woo Jun Winter 2021 Large amount of material adapted from MIT 6.004, “Computation Structures”, Morgan Kaufmann “Computer Organization and Design: The Hardware/Software Interface: RISC-V Edition”, and CS 152 Slides by Isaac Scherson Eight great ideas ❑ Design for Moore’s Law ❑ Use abstraction to simplify design ❑ Make the common case fast ❑ Performance via parallelism ❑ Performance via pipelining ❑ Performance via prediction ❑ Hierarchy of memories ❑ Dependability via redundancy But before we start… Performance Measures ❑ Two metrics when designing a system 1. Latency: The delay from when an input enters the system until its associated output is produced 2. Throughput: The rate at which inputs or outputs are processed ❑ The metric to prioritize depends on the application o Embedded system for airbag deployment? Latency o General-purpose processor? Throughput Performance of Combinational Circuits ❑ For combinational logic o latency = tPD o throughput = 1/t F and G not doing work! PD Just holding output data X F(X) X Y G(X) H(X) Is this an efficient way of using hardware? Source: MIT 6.004 2019 L12 Pipelined Circuits ❑ Pipelining by adding registers to hold F and G’s output o Now F & G can be working on input Xi+1 while H is performing computation on Xi o A 2-stage pipeline! o For input X during clock cycle j, corresponding output is emitted during clock j+2. Assuming ideal registers Assuming latencies of 15, 20, 25… 15 Y F(X) G(X) 20 H(X) 25 Source: MIT 6.004 2019 L12 Pipelined Circuits 20+25=45 25+25=50 Latency Throughput Unpipelined 45 1/45 2-stage pipelined 50 (Worse!) 1/25 (Better!) Source: MIT 6.004 2019 L12 Pipeline conventions ❑ Definition: o A well-formed K-Stage Pipeline (“K-pipeline”) is an acyclic circuit having exactly K registers on every path from an input to an output. -

Threading SIMD and MIMD in the Multicore Context the Ultrasparc T2

Overview SIMD and MIMD in the Multicore Context Single Instruction Multiple Instruction ● (note: Tute 02 this Weds - handouts) ● Flynn’s Taxonomy Single Data SISD MISD ● multicore architecture concepts Multiple Data SIMD MIMD ● for SIMD, the control unit and processor state (registers) can be shared ■ hardware threading ■ SIMD vs MIMD in the multicore context ● however, SIMD is limited to data parallelism (through multiple ALUs) ■ ● T2: design features for multicore algorithms need a regular structure, e.g. dense linear algebra, graphics ■ SSE2, Altivec, Cell SPE (128-bit registers); e.g. 4×32-bit add ■ system on a chip Rx: x x x x ■ 3 2 1 0 execution: (in-order) pipeline, instruction latency + ■ thread scheduling Ry: y3 y2 y1 y0 ■ caches: associativity, coherence, prefetch = ■ memory system: crossbar, memory controller Rz: z3 z2 z1 z0 (zi = xi + yi) ■ intermission ■ design requires massive effort; requires support from a commodity environment ■ speculation; power savings ■ massive parallelism (e.g. nVidia GPGPU) but memory is still a bottleneck ■ OpenSPARC ● multicore (CMT) is MIMD; hardware threading can be regarded as MIMD ● T2 performance (why the T2 is designed as it is) ■ higher hardware costs also includes larger shared resources (caches, TLBs) ● the Rock processor (slides by Andrew Over; ref: Tremblay, IEEE Micro 2009 ) needed ⇒ less parallelism than for SIMD COMP8320 Lecture 2: Multicore Architecture and the T2 2011 ◭◭◭ • ◮◮◮ × 1 COMP8320 Lecture 2: Multicore Architecture and the T2 2011 ◭◭◭ • ◮◮◮ × 3 Hardware (Multi)threading The UltraSPARC T2: System on a Chip ● recall concurrent execution on a single CPU: switch between threads (or ● OpenSparc Slide Cast Ch 5: p79–81,89 processes) requires the saving (in memory) of thread state (register values) ● aggressively multicore: 8 cores, each with 8-way hardware threading (64 virtual ■ motivation: utilize CPU better when thread stalled for I/O (6300 Lect O1, p9–10) CPUs) ■ what are the costs? do the same for smaller stalls? (e.g. -

Pipelined Computations

Pipelined Computations 1 Functional Decomposition car manufacturing with three plants speedup for n inputs in a p-stage pipeline 2 Pipeline Implementations processors in a ring topology pipelined addition pipelined addition with MPI MCS 572 Lecture 27 Introduction to Supercomputing Jan Verschelde, 15 March 2021 Introduction to Supercomputing (MCS 572) Pipelined Computations L-27 15 March 2021 1 / 27 Pipelined Computations 1 Functional Decomposition car manufacturing with three plants speedup for n inputs in a p-stage pipeline 2 Pipeline Implementations processors in a ring topology pipelined addition pipelined addition with MPI Introduction to Supercomputing (MCS 572) Pipelined Computations L-27 15 March 2021 2 / 27 car manufacturing Consider a simplified car manufacturing process in three stages: (1) assemble exterior, (2) fix interior, and (3) paint and finish: input sequence - - - - c5 c4 c3 c2 c1 P1 P2 P3 The corresponding space-time diagram is below: space 6 P3 c1 c2 c3 c4 c5 P2 c1 c2 c3 c4 c5 P1 c1 c2 c3 c4 c5 - time After 3 time units, one car per time unit is completed. Introduction to Supercomputing (MCS 572) Pipelined Computations L-27 15 March 2021 3 / 27 p-stage pipelines A pipeline with p processors is a p-stage pipeline. Suppose every process takes one time unit to complete. How long till a p-stage pipeline completes n inputs? A p-stage pipeline on n inputs: After p time units the first input is done. Then, for the remaining n − 1 items, the pipeline completes at a rate of one item per time unit. ) p + n − 1 time units for the p-stage pipeline to complete n inputs.