Tree Hollows ESSENTIAL for WILDLIFE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAG Operational Structure

PARROT TAXON ADVISORY GROUP (TAG) Regional Collection Plan 5th Edition 2020-2025 Sustainability of Parrot Populations in AZA Facilities ...................................................................... 1 Mission/Objectives/Strategies......................................................................................................... 2 TAG Operational Structure .............................................................................................................. 3 Steering Committee .................................................................................................................... 3 TAG Advisors ............................................................................................................................... 4 SSP Coordinators ......................................................................................................................... 5 Hot Topics: TAG Recommendations ................................................................................................ 8 Parrots as Ambassador Animals .................................................................................................. 9 Interactive Aviaries Housing Psittaciformes .............................................................................. 10 Private Aviculture ...................................................................................................................... 13 Communication ........................................................................................................................ -

Conservation Advice Polytelis Swainsonii Superb Parrot

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister approved this conservation advice on 5 May 2016; and confirmed this species 16 July 2000 inclusion in the Vulnerable category. Conservation Advice Polytelis swainsonii superb parrot Taxonomy Conventionally accepted as Polytelis swainsonii (Desmarest, 1826). Summary of assessment Conservation status Vulnerable: Criterion 1 A4(a)(c) The highest category for which Polytelis swainsonii is eligible to be listed is Vulnerable. Polytelis swainsonii has been found to be eligible for listing under the following listing categories: Criterion 1: A4(a)(c): Vulnerable Species can be listed as threatened under state and territory legislation. For information on the listing status of this species under relevant state or territory legislation, see http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Reason for conservation assessment by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee The superb parrot was listed as Endangered under the predecessor to the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) the Endangered Species Protection Act 1992 and transferred to the EPBC Act in June 2000. This advice follows assessment of information provided by public nomination to change the listing status of Polytelis swainsonii. Public Consultation Notice of the proposed amendment and a consultation document was made available for public comment for greater than 30 business days between 17 November 2014 and 9 January 2015. Any comments received that were relevant to the survival of the species were considered by the Committee as part of the assessment process. Species Information Description The superb parrot is a medium-sized (36–42 cm long; 133–157 g weight) slender, long-tailed green parrot. -

Breeding Ecology of the Superb Parrot, Polytelis Swainsonii In

Technical Report Breeding ecology of the superb parrot Polytelis swainsonii in northern Canberra Laura Rayner, Dejan Stojanovic, Robert Heinsohn and Adrian Manning Fenner School of Environment and Society The Australian National University This report was prepared for Environment and Planning Directorate Australian Capital Territory Government Technical Report: Superb parrot breeding in northern Canberra Acknowledgements This technical report was prepared by Professor Adrian D. Manning and Dr Laura Rayner of the Fenner School of Environment and Society (ANU). Professor Robert Heinsohn and Dr Dejan Stojanovic of the Fenner School of Environment and Society (ANU) were integral to the design and execution of research contained within. Mr Chris Davey contributed many hours of nest searching and monitoring to this project. In addition, previous reports of superb parrot breeding in the study area, prepared by Mr Davey for the Canberra Ornithologists Group, provided critical baseline data for this work. Dr Laura Rayner and Dr Dejan Stojanovic undertook all bird banding, transmitter deployment and the majority of nest checks and tree climbing. Mr Henry Cook contributed substantially to camera maintenance and transmitter retrieval. Additional field assistance was provided by Chloe Sato, Steve Holliday, Jenny Newport and Naomi Treloar. Funding and equipment support were provided by Senior Environmental Planner Dr Michael Mulvaney of the Environment and Planning Directorate (Environment Division) and Ecologist Dr Richard Milner of the Territory and Municipal Services Directorate (ACT Parks and Conservation Service). Spatial data of superb parrot breeding trees and flight paths for the Canberra region were provided by the ACT Conservation Planning and Research Directorate, (ACT Government). Mr Daniel Hill and Mr Peter Marshall of Canberra Contractors facilitated access to a nest tree located within the Throsby Development Area. -

Species Threatenedsuperb Parrot Polytelis Swainsonii

Australian Species ThreatenedSuperb Parrot Polytelis swainsonii CONSERVATION STATUS COMMONWEALTH: Vulnerable (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999) AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY: Vulnerable (Nature Conservation Act 1980) NEW SOUTH WALES: Vulnerable (Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995) VICTORIA: Threatened (and listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988) The Superb Parrot is a striking bird found in central woodland areas of southern WHERE DOES IT LIVE? New South Wales (NSW), the Australian The parrots are found in the NSW Capital Territory (ACT) and Victoria. southwest slopes as well as northern Already under threat from land clearing, parts of the ACT and north central loss of hollows, and lack of regeneration Victoria. Each spring they retreat towards of woodland habitat, this species may the southwest to breed, mainly in River soon be faced with another challenge and Blakely’s red gums. They then – the common myna bird. move further north and east, relying on Photo: Katherine Miller woodland habitat for flowers, fruits and seed, particularly in box and Blakely’s red gum. As one of the many Australian WHAT DOES IT bird species that uses tree hollows for breeding, clearing of woodland areas DID YOU KNOW... LOOK LIKE? has had a large impact on the parrot and, • The total population of the Superb The Superb Parrot is a medium-sized with minimal replacement of old trees, Parrot is estimated to be only a few bird with a long slender tail. Both males its numbers may continue to decline in thousand birds and females have a green body, although the future. • It is the official emblem of NSW’s the plumage on males tends to be more Boorowa Shire brilliant. -

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan Version 2: 29 July 2020 PLAN DATE PREPARED FOR CWP Renewables Pty Ltd Bango Wind Farm Contact 1: Leanne Cross P. (02) 4013 4640 M. 0416 932 549 E. [email protected] Contact 2: Alana Gordijn P. (02) 6100 2122 M. 0414 934 538 E. [email protected] PREPARED BY Dr Laura Rayner P. (02) 6207 7614 M. 0418 414 487 E. [email protected] on behalf of The National Superb Parrot Recovery Team BACKGROUND The Superb Parrot ................................................................................................................................................................2 PURPOSE Commonwealth compliance .......................................................................................................................................................2 PROJECT OVERVIEW Primary aims of proposed research ...................................................................................................................3 SCOPE OF WORK Objectives and approach of proposed research ...................................................................................................3 PROJECT A Understanding local and regional movements of Superb Parrots ....................................................................................................... 3 PROJECT B Understanding the breeding ecology and conservation status of Superb Parrots .......................................................................... 3 SIGNIFICANCE Alignment of project aims with recovery plan objectives -

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan

Superb Parrot Conservation Research Plan PLAN DATE 17 August 2020 PREPARED FOR Coppabella Wind Farm Pty Ltd Coppabella (Yass Valley) Wind Farm Contact: Medard Boutry P. (02) 9008 1728 E. [email protected] PREPARED BY Dr Laura Rayner P. (02) 6207 7614 M. 0466 391 722 E. [email protected] on behalf of The National Superb Parrot Recovery Team BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 PURPOSE ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 PROJECT OVERVIEW ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 SCOPE OF WORK ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 SIGNIFICANCE ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Breeding Ecology of the Superb Parrot Polytelis Swainsonii in Northern Canberra

Technical Report Breeding ecology of the superb parrot Polytelis swainsonii in northern Canberra Nest Monitoring Report 2016 Laura Rayner, Dejan Stojanovic, Robert Heinsohn and Adrian Manning Fenner School of Environment and Society Australian National University This report was prepared for Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate Australian Capital Territory Government Technical Report II: Superb parrot breeding in northern Canberra 2016 Acknowledgements This technical report was prepared by Professor Adrian D. Manning and Dr Laura Rayner of the Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University (ANU). Professor Robert Heinsohn and Dr Dejan Stojanovic of the Fenner School of Environment and Society (ANU) contributed to conceptualisation of research within. Chris Davey contributed many hours of nest searching and monitoring to this project. In addition, previous reports of superb parrot breeding in the study area, prepared by Davey for the Canberra Ornithologists Group, provided critical baseline data for this work. Henry Cook contributed to nest checks and camera maintenance. Field assistance was provided by Dr Chloe Sato and Lachlan Bailey. Funding and administrative support was provided by Dr Michael Mulvaney, Dr Richard Milner, Dr Margaret Kitchin and Clare McInnes of the Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate, ACT Government. Disclaimers The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Capital Territory Government. Knowledge and understanding of many aspects of the superb parrot's ecology and biology may be imperfect, uncertain or non-existent. The Superb Parrot is listed as Vulnerable in the ACT, and at Commonwealth and international levels. -

The Following Is a Section of a Document Properly Cited As: Snyder, N., Mcgowan, P., Gilardi, J., and Grajal, A. (Eds.) (2000) P

The following is a section of a document properly cited as: Snyder, N., McGowan, P., Gilardi, J., and Grajal, A. (eds.) (2000) Parrots. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan 2000–2004. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. x + 180 pp. © 2000 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the World Parrot Trust It has been reformatted for ease of use on the internet . The resolution of the photographs is considerably reduced from the printed version. If you wish to purchase a printed version of the full document, please contact: IUCN Publications Unit 219c Huntingdon Road, Cambridge, CB3 0DL, UK. Tel: (44) 1223 277894 Fax: (44) 1223 277175 Email: [email protected] The World Parrot Trust World Parrot Trust UK World Parrot Trust USA Order on-line at: Glanmor House PO Box 353 www.worldparrottrust.org Hayle, Cornwall Stillwater, MN 55082 TR27 4HB, United Kingdom Tel: 651 275 1877 Tel: (44) 1736 753365 Fax: 651 275 1891 Fax (44) 1736 751028 Island Press Box 7, Covelo, California 95428, USA Tel: 800 828 1302, 707 983 6432 Fax: 707 983 6414 E-mail: [email protected] Order on line: www.islandpress.org The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or the Species Survival Commission. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK. Copyright: © 2000 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources and the World Parrot Trust Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. -

Princess Parrot.Pdf

Husbandry Guidelines for Princess Parrots Polytelis alexandrae SALLY FLEW 1 ` Husbandry Guidelines for Princess Parrot Polytelis alexandrae (Aves : Psittacidae) Compiled by: Ms Sally Anne Flew Date of Preparation: 2009-10 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Certificate 3 Captive Animals RUV 30204 Lecturer: Graeme Phipps, Jackie Salkeld, Brad Walker. Husbandry Guidelines for Princess Parrots Polytelis alexandrae SALLY FLEW 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2 TAXONOMY ...................................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.1 NOMENCLATURE .................................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.2 SUBSPECIES .......................................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.3 RECENT SYNONYMS ............................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 2.4 OTHER COMMON NAMES ..................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 3 NATURAL HISTORY ....................................................... ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 3.1 MORPHOMETRICS ................................................................. ERROR! BOOKMARK NOT DEFINED. 3.1.1 Mass And Basic Body Measurements ...................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism .................................................................. Error! Bookmark not defined. -

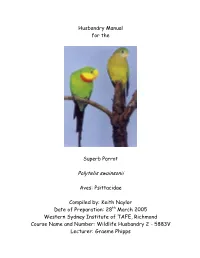

Husbandry Manual for the Superb Parrot

Husbandry Manual for the Superb Parrot Polytelis swainsonii Aves: Psittacidae Compiled by: Keith Naylor Date of Preparation: 28th March 2005 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: Wildlife Husbandry 2 - 5883V Lecturer: Graeme Phipps Animal Care Studies - Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond This husbandry manual was produced by Keith Naylor at TAFE N.S.W. – Western Sydney Institute, Richmond College, N.S.W. as part of the assessment for completion of the Animal Care Studies Course No. 8128. Keith Naylor 28/3/2005 Version 3 2 Animal Care Studies - Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 7 2 TAXONOMY 8 2.1 Nomenclature 8 2.2 Subspecies 8 2.3 Recent Synonyms 8 2.4 Other Common Names 8 3 NATURAL HISTORY 9 3.1 Morphometrics (Key Measurements and Features) 9 3.1.1 Mass and Basic Body Measurements 9 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism 9 3.1.3 Distinguishing Features 10 3.2 Distribution and Habitat 11 (Breeding, Post Breeding Dispersal and Habitat Use) 3.3 Conservation Status 20 3.4 Diet in the Wild 20 3.5 Longevity 22 3.5.1 In the Wild 22 3.5.2 In Captivity 22 3.5.3 Techniques Used to Determine Age in Adults 22 4 HOUSING REQUIREMENTS 23 4.1 Exhibit/Enclosure Design 23 4.2 Holding Area Design 33 4.3 Spatial Requirements 33 4.4 Position of Enclosures 34 4.5 Weather Protection 34 4.6 Temperature Requirements 34 4.7 Substrate 34 4.8 Nestboxes and/or Bedding Material 36 4.9 Enclosure Furnishings 36 5 GENERAL HUSBANDRY 37 5.1 Hygiene and Cleaning 37 5.2 Record Keeping 40 5.3 Methods of Identification -

Forest Ecology and Management Xxx (Xxxx) Xxx

Forest Ecology and Management xxx (xxxx) xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Suitable nesting sites for specialized cavity dependent wildlife are rare in woodlands Dejan Stojanovic a,*,1, Laura Rayner b,1, Mclean Cobden a, Chris Davey 2, Stuart Harris b, Robert Heinsohn a, Giselle Owens a, Adrian D. Manning a a Fenner School, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia b ACT Parks and Conservation Service, Australian Capital Territory Government, Canberra, Australia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Non-excavating species that prefer rare combinations of cavity traits are limited to only a fraction of the available Tree hollow tree cavity resource. Understanding animal preferences and quantifying the abundance of suitable cavities is Nest hollow fundamental to protecting non-excavators. We aimed to identify the traits of trees and cavities selected by a Habitat selection vulnerable, non-excavating bird, the superb parrot Polytelis swainsonii. We also evaluated cavity abundance and Deforestation the accuracy of ground-based survey techniques (where an observer estimated the number of cavities in the Ground survey methods Carrying capacity canopy with binoculars from the ground). We then climbed trees to accurately identify true cavities and to Superb Parrot Polytelis swainsonii measure their internal dimensions. Ground-based counts of tree cavities were correlated with the true number of cavity entrances in trees. When trees had zero cavities, ground counts overestimated their abundance, but for cavity-bearing trees ground counts underestimated their abundance. We found that superb parrot nest trees contained more cavities than random trees. Superb parrots selected cavities that were deeper, with wider floors and entrance sizes than random cavities. -

Resolving a Phylogenetic Hypothesis for Parrots: Implications from Systematics to Conservation

Emu - Austral Ornithology ISSN: 0158-4197 (Print) 1448-5540 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/temu20 Resolving a phylogenetic hypothesis for parrots: implications from systematics to conservation Kaiya L. Provost, Leo Joseph & Brian Tilston Smith To cite this article: Kaiya L. Provost, Leo Joseph & Brian Tilston Smith (2017): Resolving a phylogenetic hypothesis for parrots: implications from systematics to conservation, Emu - Austral Ornithology To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01584197.2017.1387030 View supplementary material Published online: 01 Nov 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 51 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=temu20 Download by: [73.29.2.54] Date: 13 November 2017, At: 17:13 EMU - AUSTRAL ORNITHOLOGY, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/01584197.2017.1387030 REVIEW ARTICLE Resolving a phylogenetic hypothesis for parrots: implications from systematics to conservation Kaiya L. Provost a,b, Leo Joseph c and Brian Tilston Smithb aRichard Gilder Graduate School, American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA; bDepartment of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA; cAustralian National Wildlife Collection, National Research Collections Australia, CSIRO, Canberra, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Advances in sequencing technology and phylogenetics have revolutionised avian biology by Received 27 April 2017 providing an evolutionary framework for studying natural groupings. In the parrots Accepted 21 September 2017 (Psittaciformes), DNA-based studies have led to a reclassification of clades, yet substantial gaps KEYWORDS remain in the data gleaned from genetic information.