Wilderness in the Circumpolar North

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Law 96-487 (ANILCA)

APPENDlX - ANILCA 587 94 STAT. 2418 PUBLIC LAW 96-487-DEC. 2, 1980 16 usc 1132 (2) Andreafsky Wilderness of approximately one million note. three hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge" dated April 1980; 16 usc 1132 {3) Arctic Wildlife Refuge Wilderness of approximately note. eight million acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "ArcticNational Wildlife Refuge" dated August 1980; (4) 16 usc 1132 Becharof Wilderness of approximately four hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "BecharofNational Wildlife Refuge" dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (5) Innoko Wilderness of approximately one million two note. hundred and forty thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Innoko National Wildlife Refuge", dated October 1978; 16 usc 1132 (6} Izembek Wilderness of approximately three hundred note. thousand acres as �enerally depicted on a map entitied 16 usc 1132 "Izembek Wilderness , dated October 1978; note. (7) Kenai Wilderness of approximately one million three hundred and fifty thousand acres as generaJly depicted on a map entitled "KenaiNational Wildlife Refuge", dated October 16 usc 1132 1978; note. (8) Koyukuk Wilderness of approximately four hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "KoxukukNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (9) Nunivak Wilderness of approximately six hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon DeltaNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 {10} Togiak Wilderness of approximately two million two note. hundred and seventy thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Togiak National Wildlife Refuge", dated July 16 usc 1132 1980; note. -

Togiak National Wildlife Refuge and Welcome to Togiak National Wildlife Refuge

, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Togiak National Wildlife Refuge and welcome to Togiak National Wildlife Refuge. This southwestern corner of Alaska is the ancestral home of Yup 'ik Eskimos and the abundant fish and wildlife that continue to support the people of the region. Jotldik Creek' i 290] wxvw.rulK'rtKli'iinkiulmm.com Circle of Life Togiak Refuge is home to at least 283 species of wildlife, including 33 kinds offish, 201 birds, 31 land mammals, 17 marine mammals, and 1 amphibian — the wood frog. Not everyone lives here all year, however. Only the most hardy or those that can hibernate are found on the Refuge when snow blankets the land and temperatures fall to -30"F, making food scarce. Sportfishing opportunities The Bering Sea of the North Pacific In April and May flocks of migratory attract anglers Ocean washes the shores of Togiak birds arrive by the tens of thousands from around National Wildlife Refuge while and hibernating wildlife awaken to search for new plant growth in the the world. clouds catch in the glacier-carved inland peaks. Great migrations of longer daylight hours. salmon fight their way upstream in the many rivers that flow from As the rivers thaw, the first of the mountains, providing a nutrient- more than a million salmon begin rich link between ocean and land- to migrate up Refuge rivers to based ecosystems. spawn. Wildflowers bloom in a changing panorama of colors. Togiak Refuge covers 4.7 million New life is everywhere. acres, which is a land and water area about the size of Connecticut and Animal activity soon shifts to intense Rhode Island combined. -

2007 Annual Lands Report

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Annual Report of Lands Under Control of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service as of September 30, 2007 On the cover: contamination from nuclear weapons With approximately 16 miles of trails, Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge production. thousands of acres of grassland habitat, (A unit of the National Wildlife Refuge and a beautiful mountain backdrop, System) Rocky Flats NWR contains a healthy Rocky Flats NWR will provide many expanse of grasslands, tall upland shrub opportunities for wildlife-dependent Established by the Rocky Flats National communities, and wetlands, including recreation such as hiking and wildlife Wildlife Refuge Act of 2001 (Pub. L. rare, xeric tallgrass prairie. The refuge photography. In addition, the refuge 107-107, 115 Stat. 1012, 1380-1387), will be managed to restore and protect will contain visitor use facilities, a visitor Rocky Flats National Wildlife Refuge native ecosystems; provide habitat for, contact station, interpretive overlooks, officially became the newest national and population management of, native viewing blinds, and parking. The refuge wildlife refuge when the U.S. Department plants and migratory and resident will also provide environmental education, of Energy transferred nearly 4,000 wildlife (including birds, mammals, and a limited hunting program, acres to the Service. A former nuclear river-dependent species); conserving and interpretive programs. defense facility, Rocky Flats is located threatened and endangered species 16 miles northwest of Denver, CO, at the (including Preble’s meadow jumping Cover Photo By: intersection of Jefferson, Boulder, and mouse); and providing opportunities for ©Mike Mauro (Used with his permission) Broomfield Counties. Transfer of the land compatible scientific research. -

TOGIAK NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Dillingham, Alaska ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT Calendar Year 1985 U.S. Department of the Interior Fi

TOGIAK NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Dillingham, Alaska ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT Calendar Year 1985 U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife service NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SYSTEM REVIE~l AND APPROVALS TOGIAK NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Dillingham, Alaska ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT Calendar Year 1985 Jadtk Refuge Manager Date TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION i - v A. HIGHLIGHTS 1 B. CLIMATIC CONDITIONS 1 C. LAND ACQUISITION 1. Fee Title ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 2. Easements ••••••• 5 3. Other • .•.••••••• 5 D. PLANNING 1. Master Plan ••••••• 9 2. Management Plan ••• • ••• 12 3. Public Participation •••• • ••• 12 4. Compliance with Environmental and Cultural Resource Mandates ••• NTR 5. Research and Investigations •••••••••••••••• . .••.•••••••..•.•• 12 6. Other • •.•...•••••..•.•••••••...••••• • •• Nothing to Report E. ADMINISTRATION 1. Personnel •••••••• ......................... 37 2. Youth Programs ••• •••••••••• Nothing to Report 3. Other Manpower Programs ••• •••• Nothing to Report 4. Volunteer Programs ••••• • •• 39 5. Funding . .............. .... 43 6. Safety . ............... .. 44 7. Technical Assistance •••• • ••• Nothing to Report 8. Other . ....................... .•••••..•....••.....•.....• 45 F. HABITAT MANAGEMENT 1. General •••• ..... 47 2. Wetlands ••• ..... 49 3. Forests •••• • ••• Nothing to Report 4. Croplands •• • ••• Nothing to Report 5. Grasslands ••••• ..Nothing to Report 6. Other Habitats •• . ............... 49 7. Grazing ••••••••••• ..Nothing to Report 8. Haying .. ........ • ••• Nothing to Report 9. Fire Management -

Page 1464 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION § 1132

§ 1132 TITLE 16—CONSERVATION Page 1464 Department and agency having jurisdiction of, and reports submitted to Congress regard- thereover immediately before its inclusion in ing pending additions, eliminations, or modi- the National Wilderness Preservation System fications. Maps, legal descriptions, and regula- unless otherwise provided by Act of Congress. tions pertaining to wilderness areas within No appropriation shall be available for the pay- their respective jurisdictions also shall be ment of expenses or salaries for the administra- available to the public in the offices of re- tion of the National Wilderness Preservation gional foresters, national forest supervisors, System as a separate unit nor shall any appro- priations be available for additional personnel and forest rangers. stated as being required solely for the purpose of managing or administering areas solely because (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classi- they are included within the National Wilder- fications as primitive areas; Presidential rec- ness Preservation System. ommendations to Congress; approval of Con- (c) ‘‘Wilderness’’ defined gress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Ea- A wilderness, in contrast with those areas gles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado where man and his own works dominate the The Secretary of Agriculture shall, within ten landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where years after September 3, 1964, review, as to its the earth and its community of life are un- suitability or nonsuitability for preservation as trammeled by man, where man himself is a visi- wilderness, each area in the national forests tor who does not remain. An area of wilderness classified on September 3, 1964 by the Secretary is further defined to mean in this chapter an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its of Agriculture or the Chief of the Forest Service primeval character and influence, without per- as ‘‘primitive’’ and report his findings to the manent improvements or human habitation, President. -

Togiak National Wildlife Refuge

TOGIAK NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Dillingham, Alaska ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT Calendar Year 1991 U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SYSTEM REVIEW AND APPROVALS REVIEW AND APPROVALS TOGIAK NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE Dillingham, Alaska ANNUAL NARRATIVE REPORT Calendar Year 1991 , N?? Regional Office Approval Date US FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE--ALASKA Ill~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 3 4982 00022058 1 INTRODUCfiON Togiak National Wildlife Refuge encompasses 4. 7 million acres of land in southwestern Alaska between Kuskokwim Bay and Bristol Bay. The eastern boundary of the refuge is about 400 air miles southwest of Anchorage. The refuge is bordered on the north by Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge and on the east by Wood-Tikchik State Park. The refuge contains a variety of landscapes, including tundra, lakes, wetlands, mountains, and rugged cliffs. The Kanektok, Goodnews and Togiak rivers provide habitat necessary for five species of salmon and other fish that spawn in the refuge. More than 30 species of mammals are present including brown bear, moose, caribou, wolves, and wolverine. Sea lions, walrus, and harbor seals inhabit the Pacific coast shoreline. The Refuge's coastal lakes and wetlands are also heavily used by migrating waterfowl. Southwest Alaska, Togiak National Wildlife Refuge is shaded. The former Cape Newenham National Wildlife Refuge (created in 1969) became part of the present Togiak National Wildlife Refuge. The northern 2.3 million acres of the refuge are designated wilderness. Eighty percent of the refuge is located in the Ahklun Mountains, where large expanses of tundra uplands are cut by several broad glacial valleys expanding to the coastal plain. -

Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

APPENDIX - ANILCA 537 XXIII. APPENDIX 1. Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act PUBLIC LAW 96–487—DEC. 2, 1980 94 STAT. 2371 Public Law 96–487 96th Congress An Act To provide for the designation and conservation of certain public lands in the State Dec. 2, 1980 of Alaska, including the designation of units of the National Park, National [H.R. 39] Wildlife Refuge, National Forest, National Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Wilderness Preservation Systems, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Alaska National SECTION 1. This Act may be cited as the “Alaska National Interest Lands Interest Lands Conservation Act”. Conservation Act. TABLE OF CONTENTS 16 USC 3101 note. TITLE I—PURPOSES, DEFINITIONS, AND MAPS Sec. 101. Purposes. Sec. 102. Definitions. Sec. 103. Maps. TITLE II—NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM Sec. 201. Establishment of new areas. Sec. 202. Additions to existing areas. Sec. 203. General administration. Sec. 204. Native selections. Sec. 205. Commercial fishing. Sec. 206. Withdrawal from mining. TITLE III—NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SYSTEM Sec. 301. Definitions. Sec. 302. Establishment of new refuges. Sec. 303. Additions to existing refuges. Sec. 304. Administration of refuges. Sec. 305. Prior authorities. Sec. 306. Special study. TITLE IV—NATIONAL CONSERVATION AREA AND NATIONAL RECREATION AREA Sec. 401. Establishment of Steese National Conservation Area. Sec. 402. Administrative provisions. Sec. 403. Establishment of White Mountains National Recreation Area. Sec. 404. Rights of holders of unperfected mining claims. TITLE V—NATIONAL FOREST SYSTEM Sec. 501. Additions to existing national forests. -

Including Pegati and Kagati Lakes)

United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT Alaska State Office 222 West Seventh Avenue, #13 Anchorage, Alaska 9951 3-7504 www.blm.%ov/alaska AUG 072078 In Reply Refer To: 1864 (LLAK941O) Memorandum To: File AA-93210 From: Jack Frost, Navigable Water Specialist (LLAK941O) Subject: Summary Report on Federal Interest in Lands underlying the Kanektok River System (including Pegati and Kagati lakes) On Feb. 28, 2012, the State of Alaska (State) filed an application for a recordable disclaimer of interest (RDI) with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for lands underlying the Kanektok River including Pegati and Kagati lakes. Specifically, the State applied for a disclaimer of the United States’ interest in “the submerged lands and bed up to and including the ordinary high water line of Pegati and Kagati lakes within Township 03 & 04 South, Range 63 West, Seward Meridian, Alaska and for the submerged lands and bed of the Kanektok River lying between the ordinary high water marks of the right and left banks of that river from the outlet of Pegati Lake within Township 03 South, Range 63 West, Seward Meridian, Alaska, downstream to the location where the river enters the Kuskokwim Bay in Township 05 South, Range 74 West, Seward Meridian, Alaska.” The land description and maps for the Kanektok River and Pegati and Kagati lakes can be found in the State’s application.’ The State’s applications for disclaimers of interest are based on the Equal Footing Doctrine, the Submerged Lands Act of May 22, 1953, the Alaska Statehood Act, the Submerged Lands Act of 1988, or any other legally cognizable reason. -

The Wilderness Act of 1964

The Wilderness Act of 1964 Source: US House of Representatives Office of the Law This is the 1964 act that started it all Revision Counsel website at and created the first designated http://uscode.house.gov/download/ascii.shtml wilderness in the US and Nevada. This version, updated January 2, 2006, includes a list of all wilderness designated before that date. The list does not mention designations made by the December 2006 White Pine County bill. -CITE- 16 USC CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM 01/02/2006 -EXPCITE- TITLE 16 - CONSERVATION CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -HEAD- CHAPTER 23 - NATIONAL WILDERNESS PRESERVATION SYSTEM -MISC1- Sec. 1131. National Wilderness Preservation System. (a) Establishment; Congressional declaration of policy; wilderness areas; administration for public use and enjoyment, protection, preservation, and gathering and dissemination of information; provisions for designation as wilderness areas. (b) Management of area included in System; appropriations. (c) "Wilderness" defined. 1132. Extent of System. (a) Designation of wilderness areas; filing of maps and descriptions with Congressional committees; correction of errors; public records; availability of records in regional offices. (b) Review by Secretary of Agriculture of classifications as primitive areas; Presidential recommendations to Congress; approval of Congress; size of primitive areas; Gore Range-Eagles Nest Primitive Area, Colorado. (c) Review by Secretary of the Interior of roadless areas of national park system and national wildlife refuges and game ranges and suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; authority of Secretary of the Interior to maintain roadless areas in national park system unaffected. (d) Conditions precedent to administrative recommendations of suitability of areas for preservation as wilderness; publication in Federal Register; public hearings; views of State, county, and Federal officials; submission of views to Congress. -

Togiak CCP Comments 1=08

791 Redpoll Ln Fairbanks, Alaska 99712 January 18, 2008 Maggie Arend Planning Team Leader U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1011 East Tudor Road, MS 231 Anchorage, AK 99503 Re: Public Comments on Draft Revised Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Public Use Management Plans EIS for Togiak National Wildlife Refuge Dear Ms Arend: Please accept the following comments on behalf of the Alaska Chapter of Wilderness Watch, a non-profit conservation organization dedicated to advocating for appropriate stewardship of our Nation’s National Wilderness Preservation System and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Historic Context: While the draft EIS presents a bewildering array of legal mandates, agency policies and processes, it lacks any presentation of the historic context which led to the establishment of Togiak Refuge. To be “comprehensive,” the plan should include a description of ANILCA history that tells the story of a growing national awareness that in the vast, wild landscapes of Alaska, our nation had a “second chance” to avoid making many of the land use errors that had occurred elsewhere in the U.S. This concern, and the resolve to prevent such errors is now embedded in the purposes of ANILCA (Section 101): “to preserve unrivaled scenic and geological values associated with natural landscapes …maintenance of sound populations of wildlife…dependent on vast relatively undeveloped areas; to preserve in their natural state extensive unaltered arctic tundra, boreal forest and coastal rainforest ecosystems…to preserve wilderness resource values and related recreational opportunities…within large arctic and subarctic wildlands and on freeflowing rivers and to maintain opportunities for scientific research and undisturbed ecosystems.” (emphasis added) It was in this over-arching National interest that Togiak Refuge, along with several other National Wildlife Refuges, National Parks and Preserves, National Wild Rivers and Wildernesses, were designated by Congress. -

2019 Application -Save As “Application Your Last Name” -Save As “.Pdf Or .Docx” Formatting

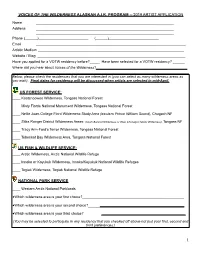

VOICES OF THE WILDERNESS ALASKAN A.I.R. PROGRAM -- 2019 ARTIST APPLICATION Name _____________________________________________________________________ Address _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Phone (______)_________________________ (______)_________________________ Email ___________________________________________________________________________ Artistic Medium _________________________________________________________________________ Website / Blog __________________________________________________________________________ Have you applied for a VOTW residency before?_____ Have been selected for a VOTW residency? ______ Where did you hear about Voices of the Wilderness? _____________________________________________ Below, please check the residencies that you are interested in (you can select as many wilderness areas as you wish). Final dates for residency will be discussed when artists are selected in mid-April. ! US FOREST SERVICE: ____ Kootznoowoo Wilderness, Tongass National Forest ____ Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness, Tongass National Forest ____ Nellie Juan-College Fiord Wilderness Study Area (western Prince William Sound), Chugach NF ____ Sitka Ranger District Wilderness Areas: (South Baranof Wilderness or West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness), Tongass NF ____ Tracy Arm-Ford’s Terror Wilderness, Tongass National Forest ____ Tebenkof Bay Wilderness Area, Tongass National Forest ! US FISH & WILDLIFE SERVICE: ____ Arctic -

Subsistenceuse on Togiak Refuge Rivers by Localresidents

This brochure was produced by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. For further information, please write: Togiak National Wildlife Refuge Bethel Chamber of Commerce P.O. Box 270 P.O. Box 329 Dillingham, AK 99576 Bethel, AK 99559 (907)8420 063 Alaska Department of Natural Resources Alaska Department of Fish & Came South Central Regional Office Sport Fisheries or Commercial Fisheries P.O.Box 107005 P.O. Box 230 Anchorage, AK 99510-7005 Dillingham, AK 99576 (907) 842-2427 or 842-5227 Bristol Bay Native Association Natural Resource Program Alaska Department of Fish & Came P.O. Box 310 Commercial Fisheries Dillingham, AK 99576 P.O. Box 90 Bethel, AK 99652 Association of Village Council Presidents Natural Resource Program Dillingham Chamber of Commerce P.O. Box 219 P.O. Box 348 Bethel, AK 99559 Dillingham, AK 99576 Camping and River Recreation Camping and fishing are permitted on public lands throughout the refuge. There are no des ignated campsites so you are free to choose a site to meet your own needs as long as it is not on private land. Camping on Togiak Refuge lands or adjacent State-owned lands is limit ed to three days at one location. At the outlet of Kagati Lake, camping is limited to one day to provide equal access for float parties and anglers. Camping on State-owned lands may be permitted for more than three days by contacting the Alaska Department of Natural Welcome Resources at the address provided on the back cover of this brochure. The rivers of the Togiak National Wildlife Refuge attract visitors from around the world.