Orthodoxy Bt the Same Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide for G.K. Chesterton's Orthodoxy1

Study Guide for G.K. Chesterton’s Orthodoxy1 By Kyle D. Rapinchuk Chapter Summaries Chapter One: Introduction Chesterton begins Orthodoxy with a statement about its origin, noting that he wrote this book in response to a challenge from G.S. Street. Street’s challenge was that Chesterton’s previous book, Heretics, merely pointed out flaws in other philosophies without ever establishing his own. In this work, then, Chesterton will set forth his philosophy, though he will not call it his, for, as he writes, “I did not make it. God and humanity made it; and it made me” (1). In this opening chapter, Chesterton tells a farcical tale of an English yachtsman who set sail, and due to a miscalculation, succeeded in discovering England, though in truth it had already been discovered. Chesterton will liken himself to this man in saying that his attempts to search for truth merely led him to discover that which had already been discovered over 1800 years before. Consequently, his plan is to lay out his own journey as one means of demonstrating how the “central Christian theology (sufficiently summarized in the Apostle’s Creed) is the best root of energy and sound ethics” (5). Chapter Two: The Maniac Chesterton begins this chapter by challenging the common notion that a man will succeed if he believes in himself. Chesterton argues the opposite—a man who believes in himself will almost certainly fail, for men are not to be trusted. “Complete self-confidence,” writes Chesterton, “is not merely a sin; complete self-confidence is a weakness” (7). -

An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Kentucky Mountain Bible College

Inklings Forever Volume 5 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fifth Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Lewis & Article 14 Friends 6-2006 An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Kentucky Mountain Bible College Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Huff, Randy (2006) "An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton," Inklings Forever: Vol. 5 , Article 14. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol5/iss1/14 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume V A Collection of Essays Presented at the Fifth FRANCES WHITE COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2006 Upland, Indiana An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff Huff, Randy. “An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton.” Inklings Forever 5 (2006) www.taylor.edu/cslewis An Apologetic for Marriage and the Family from G.K. Chesterton Randy Huff G.K. Chesterton was regarded by friend and foe as he enters, it is built wrong.”6 In the conclusion to a man of genius, a defender of the faith, a debater and What’s Wrong with the World, he sums it up thus: conversationalist par excellence. -

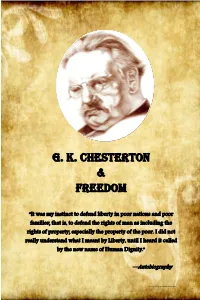

It Was My Instinct to Defend Liberty in Poor Nations and Poor Families; That Is, to Defend the Rights of Man As Including

G. K. Chesterton & G. K.Freedom Chesterton “It was my instinct to defend liberty in poor nations and poor families; that is, to defend the rights of man as including the rights of property; especially the property of the poor. I did not really understand what I meant by Liberty, until I heard it called by the new name of Human Dignity.” —Autobiography © 2012 G. K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture “The free man owns himself. He can damage himself with either eating or drinking; he can ruin himself with gambling. If he does, he is certainly a damn fool, and he might possibly be a damned soul; but if he may not, he is not a free man any more than a dog.” —Broadcast talk, June 1935 “Most modern freedom is at root fear. It is not so much that we are too bold to en- dure rules; it is rather that we are too timid to endure responsibilities.” —What’s Wrong With the World G. K. Chesterton “The man of the true religious tradition understands two things: liberty and obedience. The first means knowing what you really want. The second means knowing what you really trust.” —G. K.’s Weekly, August 18, 1933 © 2012 G. K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture Fr. Ian Boyd on Chesterton & Freedom “The two ideas upon which Christian theology was based were the ideas of Reason and Liberty.” So said Chesterton in November 1911 in his address to a meeting at Cambridge organized by a student club who called themselves “The Heretics.” He went on to say that Reason was real. -

G K Chesterton

G.K. CHESTERTON: A LIFE Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in Kensington in 1874, educated at St. Paul’s School and the Slade School of Art where it was found that his primary talents were in the direction of writing. His earliest work was done in the family home and later at the publishers’ offices of Redway and T Fisher Unwin, and in the hurly burly of Fleet Street. It was his marriage to Frances Blogg in 1901 which turned his thoughts to a permanent home where he could continue his writing and find some quiet from the busy life as a journalist. The early years of marriage were spent in Kensington and Overstrand Mansions at Battersea, and it was from the latter that one day they took a second honeymoon journey to Slough from a station they had reached by chance on a bus labelled ‘Hanwell’. From Slough they walked through the beech woods to Beaconsfield, staying at the White Hart Hotel and decided ‘This is the sort of place where someday we will make our home’. This proved possible in 1909 when they rented Overroads, which had just been built in Grove Road. Their hopes of having children had by this time faded and they busied themselves with entertaining the children of their friends. Charades and other such games were an excuse for assembling cloaks and hats, bringing swords out of the umbrella stands or sheets from the beds. Despite the disappointment, children played a great part in their life and many local children had drawings done for them, skilfully but hastily drafted and full of humour. -

The Controversy Over Modernism and in Particular the Furor That

Susan E. Hanssen DUMB OX AT THE CROSSROADS OF ENGLISH CATHOLICISM: G. K. CHESTERTOn’s “thOUGHTS NOT IN THEMSELves new” HE controversy over modernism and in particular the furor that met Pius X’s 1907 Syllabus and encyclical letter Pascendi sheds light Ton the protean figure ofG . K. Chesterton, who stands so prominent- ly in the transition between the Second and Third Spring of the English Catholic revival. Over the course of its magisterial teaching, the papacy described two different modernisms and prescribed two distinct Thomistic antidotes: Pius IX’s nineteenth-century Syllabus of Errors addressed po- litical modernism attacking the Church from without; Pius X’s twentieth- century Syllabus took aim at philosophical modernism destroying Chris- tian theology from within. This two-front battle with modernism had the unintended consequence of separating Thomas’s political thought from his metaphysical thought, creating two distinct Thomisms — social doctrine Thomism and metaphysical Thomism.1 It becomes apparent, in light of this trajectory of the modernist controversy, that Chesterton’s influence on twentieth-century converts was due largely to the fact that he elaborated the metaphysical critique of modernism in a way that earlier converts had not. “Newman gave . extraordinarily graphic descriptions of the actual mental steps involved in giving consent on the basis of common sense, but never probed into the philosophy of common sense” (Jaki 237). Ches- terton, however, was forced to go one step further than Newman, to dive for the philosophy of common sense. The translation and promotion of Nietzsche’s work in English by Chesterton’s editor at The New Age, A. -

Detective Fiction Reinvention and Didacticism in G. K. Chesterton's

Detective Fiction Reinvention and Didacticism in G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown Clifford James Stumme Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of English College of Arts and Science Liberty University Stumme 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................3 Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................................4 Historical and Autobiographical Context ....................................................................................6 Detective Fiction’s Development ..............................................................................................10 Chesterton, Detective Fiction, and Father Brown ......................................................................21 Chapter 2: Paradox as a Mode for Meaning ..................................................................................32 Solution Revealing Paradox .......................................................................................................34 Plot Progressing Paradox ...........................................................................................................38 Truth Revealing Paradox ...........................................................................................................41 Chapter 3: Opposition in Character and Ideology .........................................................................49 -

Chesterton's View of Human Nature Through Father Brown Mark Eckel Crossroads Bible College

Inklings Forever Volume 7 A Collection of Essays Presented at the Seventh Frances White Ewbank Colloquium on C.S. Article 4 Lewis & Friends 6-3-2010 Devils in My Heart: Chesterton's View of Human Nature through Father Brown Mark Eckel Crossroads Bible College Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Eckel, Mark (2010) "Devils in My Heart: Chesterton's View of Human Nature through Father Brown," Inklings Forever: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Available at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/inklings_forever/vol7/iss1/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of C.S. Lewis & Friends at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inklings Forever by an authorized editor of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INKLINGS FOREVER, Volume VII A Collection of Essays Presented at the Seventh FRANCES WHITE COLLOQUIUM on C.S. LEWIS & FRIENDS Taylor University 2010 Upland, Indiana Devils in My Heart Chesterton’s View of Human Nature through Father Brown Mark Eckel “I had murdered them all myself.”1 Father Brown perhaps comes closest to true, biblical mystery. While a crime may have been solved, the good padre still wondered after the human penchant toward sin. Sherlock Holmes fans are used to deductive reasoning: a scientific analysis, assessing problems from the outside, in. Father Brown became the murderer because he was a murderer. Chesterton‟s sleuth, a Catholic priest, saw people as they were, from the inside, out. -

Ifefigia Àpm&JM By

IfefigiA àPM & JM By PRINCIPLES Of EDUCATION IN THE WORKS W 0. K. CHESTERTON ivi BY SISTER U, CONCORDIA SCHNEOLBERGER, O .S.P. A THESIS Submitted to the Faculty of The Creighton University in P a rtia l Fulfillm ent of the Requirements fo r the Degree of lias ter of Arts in the Department of Eduoation OSAKA, 1944 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page X. INTRODUCTION . X XX* CHESTERTON THE MAN....................................... 5 XIX, PHILOSOPHY AID PRACTICE UNDERLYING MODERN EDUCATION ................... *»*».»* 15 IV, CHESTSKM*S PHILOSOPHY............................. , 21 V. GHESTERTC$f»S EDUCATIONAL WXSDOI,.................. 31 V I. EDUCATIONAL VALUES OF FAIRY TALES..................44 V I I . AN ENTIRELY CATHOLIC EDUCATION FOR THE CATHOLIC CHURCH.................................................50 V III, DOES AMERICA NEED CHESTERTON .........................56 BIBLIOGRAPHY .................................* ........................ , 63 CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION The purpose of this thesis is to analyze G ilbert Keith Chesterton's ideas on education and thereby show his view of modern educational philosophy and practices in many of our schools. After a brief description of the life and char acter of Chesterton, the writer intends to set forth the philosophy and praotices of modern education, followed by Chesterton's unsympathetic attitude toward that phi losophy and practice as gleaned from his writings* F i nally, the w riter aims to show the harmonious relation between Catholic philosophy and Chestertonian thought, concluding the study with a chapter on America's need for Chesterton* Chesterton's thoughts on education were mainly drawn from his book What Is Wrong with the v/orld. in which he expounds his views of man and man's destiny* The chapter on the mistake made about the child sheds much light on Chesterton's educational outlook* Two other books, Heretics and Orthodoxy, lent themselves splendidly to following up the philosophical trends of that great w riter. -

Faith and Reason in G. K. Chesterton's Father Brown

Faith and Reason in G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown Sara Conti G. K. Chesterton wrote a lot of detective stories, but the peculiarity of the Father Brown series is that the person who solves the mysteries of the cases is a priest of the Roman Catholic Church. Contrary to his sober appearance and his being a cleric, which gives an impression of a man who is far from reality, Father Brown is wiser and more able to face reality than any other character in the stories. It is well known that Chesterton was a religious writer, but it is also true that he had a special fondness of reality. We can see that his way of perceiving things such as‘eggs are eggs’, written in St. Thomas Aquinas, is consistent with the way of facing reality of Father Brown and also in the relationship between faith and reason. The Catholic Church asserts that faith is one of the Virtues given by God, but at the same time an act of free will. In Father Brown, on one hand, we can see Father Brown’s attitudes and words which suggest his absolute confidence in God. On the other hand, we can see also that he respects the freedom of choice of the suspects. In addition, for Father Brown, believing in God and seeing‘things as they are’ are connected. According to The Bible, faith is‘the evidence of things not seen’ (Heb: 11, 1), and as Chesterton says in Heretics, faith is a virtue because it‘means believing the incredible’. -

The Chesterton Review Are Part of the Center for Catholic Studies

G.K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture Established in 1974 G.K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture Established in 1974 About G. K. Chesterton G. K. Chesterton, (1874-1936) was an English writer. His prolific and diverse output included philosophy, poetry, plays, journalism, public lectures and debates, literary and art criticism and fiction. He has been called “the prince of paradox.” His diverse body of work and his ability to write about serious subjects in a style accessible to the ordinary reader made him one of the most beloved figures twentieth- century literature. His thought and philosophy of life are of particular importance to those who value the sacramental tradition, Catholic social teaching and Christian spirituality. His works have been translated into many languages and because his writings are the subject of study by students and scholars, they continue to reach new generations of readers. About the Institute History The G. K. Chesterton Institute for Faith & Culture founded by Father Ian Boyd in 1974 is based at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. Previously, from 1974 to 1999 the Institute was based at St. Thomas More College in Saskatchewan, Canada where Father Boyd was a member of the faculty of the English Department. Mission The purpose of the Institute is to promote the thought of G. K. Chesterton and his circle and, more broadly, to explore the application of Chestertonian ideas to the contemporary world through social and economic projects, lectures and seminars and their application in the world of today. The work of the Institute is one * of recovery through Chesterton and the tradition he represents * it proposes a re-awakening of the moral and sacramental imagination * a renewed sense of human dignity * a re-evangelization of culture * And a return to social sanity The Institute does this work through its publications is engaged in a growing programme of research, conferences and symposiums in the United States and around the world. -

GK Chesterton

THE SAGE DIGITAL LIBRARY APOLOGETICS HERETICS by Gilbert K. Chesterton To the Students of the Words, Works and Ways of God: Welcome to the SAGE Digital Library. We trust your experience with this and other volumes in the Library fulfills our motto and vision which is our commitment to you: M AKING THE WORDS OF THE WISE AVAILABLE TO ALL — INEXPENSIVELY. SAGE Software Albany, OR USA Version 1.0 © 1996 2 HERETICS by Gilbert K. Chesterton SAGE Software Albany, Oregon © 1996 3 “To My Father” 4 The Author Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in London, England on the 29th of May, 1874. Though he considered himself a mere “rollicking journalist,” he was actually a prolific and gifted writer in virtually every area of literature. A man of strong opinions and enormously talented at defending them, his exuberant personality nevertheless allowed him to maintain warm friendships with people — such as George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells — with whom he vehemently disagreed. Chesterton had no difficulty standing up for what he believed. He was one of the few journalists to oppose the Boer War. His 1922 “Eugenics and Other Evils” attacked what was at that time the most progressive of all ideas, the idea that the human race could and should breed a superior version of itself. In the Nazi experience, history demonstrated the wisdom of his once “reactionary” views. His poetry runs the gamut from the comic 1908 “On Running After One’s Hat” to dark and serious ballads. During the dark days of 1940, when Britain stood virtually alone against the armed might of Nazi Germany, these lines from his 1911 Ballad of the White Horse were often quoted: I tell you naught for your comfort, Yea, naught for your desire, Save that the sky grows darker yet And the sea rises higher. -

Orthodoxy- G.K.Chesterton (Pdf)

ORTHODOXY BY GILBERT K. CHESTERTON John Lane Company 1908 This book is in the public domain. PREFACE THIS book is meant to be a companion to “Heretics,” and to put the positive side in addition to the negative. Many critics complained of the book called “Heretics” because it merely criticised current philosophies without offering any alternative philosophy. This book is an attempt to answer the challenge. It is unavoidably affirmative and therefore unavoidably autobiographical. The writer has been driven back upon somewhat the same difficulty as that which beset Newman in writing his Apologia; he has been forced to be egotistical only in order to be sincere. While everything else may be different the motive in both cases is the same. It is the purpose of the writer to attempt an explanation, not of whether the Christian Faith can be believed, but of how he personally has come to believe it. The book is therefore arranged upon the positive principle of a riddle and its answer. It deals first with all the writer’s own solitary and sincere speculations and then with all the startling style in which they were all suddenly satisfied by the Christian Theology. The writer regards it as amounting to a convincing creed. But if it is not that it is at least a repeated and surprising coincidence. GILBERT K. CHESTERTON. CONTENTS I—Introduction in Defence of Everything Else ................................................................. 5 II—The Maniac................................................................................................................ 8 III—The Suicide of Thought........................................................................................... 17 IV—The Ethics of Elfland .............................................................................................. 26 V—The Flag of the World.............................................................................................. 37 VI—The Paradoxes of Christianity ...............................................................................