Migration and Summer Distribution of Lesser Snow Geese in Interior Keewatin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NUNAVUT a 100 , 101 H Ackett R Iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C Lve Coal T Rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H Igh Lake , Izo K Lake M M G Resources Inc

150°W 140°W 130°W 120°W 110°W 100°W 90°W 80°W 70°W 60°W 50°W 40°W 30°W PROJECTS BY REGION Note: Bold project number and name signifies major or advancing project. AR CT KITIKMEOT REGION 8 I 0 C LEGEND ° O N umber P ro ject Operato r N O C C E Commodity Groupings ÉA AN B A SE M ET A LS Mineral Exploration, Mining and Geoscience N Base Metals Iron NUNAVUT A 100 , 101 H ackett R iver , Wishbone Xstrata Zinc Canada R Ye C lve Coal T rto Nickel-Copper-PGE 102, 103 H igh Lake , Izo k Lake M M G Resources Inc. I n B P Q ay q N Diamond Active Projects 2012 U paa Rare Earth Elements 104 Hood M M G Resources Inc. E inir utt Gold Uranium 0 50 100 200 300 S Q D IA M ON D S t D i a Active Mine Inactive Mine 160 Hammer Stornoway Diamond Corporation N H r Kilometres T t A S L E 161 Jericho M ine Shear Diamonds Ltd. S B s Bold project number and name signifies major I e Projection: Canada Lambert Conformal Conic, NAD 83 A r D or advancing project. GOLD IS a N H L ay N A 220, 221 B ack R iver (Geo rge Lake - 220, Go o se Lake - 221) Sabina Gold & Silver Corp. T dhild B É Au N L Areas with Surface and/or Subsurface Restrictions E - a PRODUCED BY: B n N ) Committee Bay (Anuri-Raven - 222, Four Hills-Cop - 223, Inuk - E s E E A e ER t K CPMA Caribou Protection Measures Apply 222 - 226 North Country Gold Corp. -

Annual Report: October 1, 2014 Assessing the Impact of Small, Canadian Arctic River Flows to the Freshwater Budget of the Canadian Archipelago Matthew B

Annual Report: October 1, 2014 Assessing the impact of small, Canadian Arctic River flows to the freshwater budget of the Canadian Archipelago Matthew B. Alkire, University of Washington Assessing the impact of small, Canadian Arctic river flows to the freshwater budget of the Canadian Archipelago (or SCARFs) is a scientific research project funded by the National Science Foundation (USA). The purpose of this project is to collect water samples from seven different rivers and their adjoining estuaries throughout the Canadian Arctic Archipelago (see Fig. 1) in order to determine whether or not their chemical signatures differ from larger North American rivers such as the Mackenzie and Yukon Rivers. Five of the rivers are located within Nunavut, Canada: the Coppermine River (near Kugluktuk), Ellice River (~140 km southeast of Cambridge Bay), Back River (~180 km southeast of Gjoa Haven), Cunningham River (~77 km southeast of Resolute Bay on Somerset Island), and Kangiqtugaapik River (near Clyde River, Baffin Island). Two of the rivers are located within the Northwest Territories, Canada: the Kujjuua River (located approximately 67 km northeast of Ulukhaktok on Victoria Island) and Thomsen River (specifically near the mouth of the river where it empties into Castel Bay, on Banks Island). Figure 1. Map of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The red stars indicate the mouths of the rivers sampled during this study: (1) Coppermine R., (2) Ellice R., (3) Back R., (4) Kuujuua R. (Victoria Island), (5) Thomsen R. (Banks Island), (6) Cunningham R. (Somerset Island), and (7) Clyde R. (Baffin Island). The Coppermine, Ellice, and Back Rivers are located on the mainland of Nunavut. -

Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1

ARCTIC VOL. 71, NO.3 (SEPTEMBER 2018) P.292 – 308 https://doi.org/10.14430/arctic4733 Who Discovered the Northwest Passage? Janice Cavell1 (Received 31 January 2018; accepted in revised form 1 May 2018) ABSTRACT. In 1855 a parliamentary committee concluded that Robert McClure deserved to be rewarded as the discoverer of a Northwest Passage. Since then, various writers have put forward rival claims on behalf of Sir John Franklin, John Rae, and Roald Amundsen. This article examines the process of 19th-century European exploration in the Arctic Archipelago, the definition of discovering a passage that prevailed at the time, and the arguments for and against the various contenders. It concludes that while no one explorer was “the” discoverer, McClure’s achievement deserves reconsideration. Key words: Northwest Passage; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen RÉSUMÉ. En 1855, un comité parlementaire a conclu que Robert McClure méritait de recevoir le titre de découvreur d’un passage du Nord-Ouest. Depuis lors, diverses personnes ont avancé des prétentions rivales à l’endroit de Sir John Franklin, de John Rae et de Roald Amundsen. Cet article se penche sur l’exploration européenne de l’archipel Arctique au XIXe siècle, sur la définition de la découverte d’un passage en vigueur à l’époque, de même que sur les arguments pour et contre les divers prétendants au titre. Nous concluons en affirmant que même si aucun des explorateurs n’a été « le » découvreur, les réalisations de Robert McClure méritent d’être considérées de nouveau. Mots clés : passage du Nord-Ouest; John Franklin; Robert McClure; John Rae; Roald Amundsen Traduit pour la revue Arctic par Nicole Giguère. -

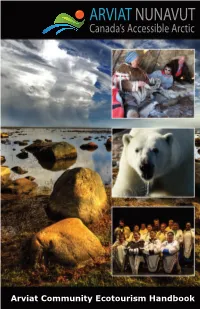

Arviat Community Ecotourism Handbook This Copy Belongs To

Arviat Community Ecotourism Handbook This copy belongs to: Front cover photo credits: Polar bear, Mark Seth Lender Landscape, Michelle Valberg Welcome to Arviat! Arviat is one of the more southerly and most accessible Inuit communities in Nunavut, Canada’s newest territory. Located on the western shores of Hudson Bay, framed in by several large barrenland rivers lies this intriguing land rich in wildlife, a flat to gently rolling landscape dotted with lakes and ponds, and steeped in Inuit culture. Arviat presents the authentic best in Nunavut tourism. If you are looking for a real arctic tourism experience Arviat offers spectacular wildlife viewing combined with an interactive cultural program providing insight into fascinating age old Inuit cultural traditions. Arviammiut (the people of Arviat) are your hosts in this magical land. We are a proud people living in harmony with the land and wildlife around us and we maintain a strong connection with our Inuit traditions and culture. This landscape has been occupied for thousands of years and much of the physical evidence of early occupations still survives due to the Arctic climate. Two National Historic Sites that can be easily accessed from the community are testament to the rich cultural heritage and resources on the land www.historicplaces.ca Come explore the land of the Inuit, with the Inuit. If you are interested in learning more about the Inuit of Arviat you can visit the Nanisiniq website: nanisiniq.tumblr.com Michelle Valberg 1 The Arviat Community Ecotourism (ACE) initiative is true community-based tourism. ACE is owned and operated by the community. -

Historical Developments in Utkuhiksalik Phonology; 5/16/04 Page 1 of 36

Carrie J. Dyck Department of Linguistics Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John’s NL A1B 3X9 Jean L. Briggs Department of Anthropology Memorial University of Newfoundland St. John’s NL A1B 3X9 Historical developments in Utkuhiksalik phonology; 5/16/04 page 1 of 36 1 Introduction* Utkuhiksalik has been analysed as a subdialect of Natsilik within the Western Canadian Inuktun (WCI) dialect continuum (Dorais, 1990:17; 41). 1 While Utkuhiksalik has much in com- mon with the other Natsilik subdialects, the Utkuhiksalingmiut and the Natsilingmiut were his- torically distinct groups (see §1.1). Today there are still lexical (see §1.2) and phonological dif- ferences between Utkuhiksalik and Natsilik. The goal of this paper is to highlight the main phonological differences by describing the Utkuhiksalik reflexes of Proto-Eskimoan (PE) *c, *y, and *D. 1.1 Overview of dialect relations2 The traditional territory of the Utkuhiksalingmiut (the people of the place where there is soapstone) lay between Chantrey Inlet and Franklin Lake. Utkuhiksalik speakers also lived in the * Research for this paper was supported by SSHRC grant #410-2000-0415, awarded to Jean Briggs. The authors would also like to acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the Utkuhiksalingmiut who presently live in Gjoa Haven, especially Briggs’s adoptive mother and aunts. Tape recordings of these consultants, collected by Briggs from the 1960’s to the present, constitute the data for this paper. Briggs is currently compiling a dictionary of Utkuhiksalik. 1 We use the term Natsilik, rather than Netsilik, to denote a dialect cluster that includes Natsilik, Utkuhik- salik, and Arviligjuaq. -

198 13. Repulse Bay. This Is an Important Summer Area for Seals

198 13. Repulse Bay. This is an important summer area for seals (Canadian Wildlife Service 1972) and a primary seal-hunting area for Repulse Bay. 14. Roes Welcome Sound. This is an important concentration area for ringed seals and an important hunting area for Repulse Bay. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 15. Southampton-Coats Island. The southern coastal area of Southampton Island is an important concentration area for ringed seals and is the primary ringed and bearded seal hunting area for the Coral Harbour Inuit. Fisher and Evans Straits and all coasts of Coats Island are important seal-hunting areas in late summer and early fall. Marine traffic, materials staging, and construction of the crossing could displace seals or degrade their habitat. 16.7.2 Communities Affected Communities that could be affected by impacts on seal populations are Resolute and, to a lesser degree, Spence Bay, Chesterfield Inlet, and Gjoa Haven. Effects on Arctic Bay would be minor. Coral Harbour and Repulse Bay could be affected if the Quebec route were chosen. Seal meat makes up the most important part of the diet in Resolute, Spence Bay, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay. It is a secondary, but still important food in Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. Seal skins are an important source of income for Spence Bay, Resolute, Coral Harbour, Repulse Bay, and Arctic Bay and a less important income source for Chesterfield Inlet and Gjoa Haven. 16.7.3 Data Gaps Major data gaps concerning impacts on seal populations are: 1. -

The Final Days of the Franklin Expedition: New Skeletal Evidence ANNE KEENLEYSIDE,1 MARGARET BERTULLI2 and HENRY C

ARCTIC VOL. 50, NO. 1 (MARCH 1997) P. 36–46 The Final Days of the Franklin Expedition: New Skeletal Evidence ANNE KEENLEYSIDE,1 MARGARET BERTULLI2 and HENRY C. FRICKE3 (Received 19 June 1996; accepted in revised form 21 October 1996) ABSTRACT. In 1992, a previously unrecorded site of Sir John Franklin’s last expedition (1845–1848) was discovered on King William Island in the central Canadian Arctic. Artifacts recovered from the site included iron and copper nails, glass, a clay pipe fragment, pieces of fabric and shoe leather, buttons, and a scatter of wood fragments, possibly representing the remains of a lifeboat or sledge. Nearly 400 human bones and bone fragments, representing a minimum of 11 men, were also found at the site. A combination of artifactual and oxygen isotope evidence indicated a European origin for at least two of these individuals. Skeletal pathology included periostitis, osteoarthritis, dental caries, abscesses, antemortem tooth loss, and periodontal disease. Mass spectroscopy and x-ray fluorescence revealed elevated lead levels consistent with previous measurements, further supporting the conclusion that lead poisoning contributed to the demise of the expedition. Cut marks on approximately one-quarter of the remains support 19th-century Inuit accounts of cannibalism among Franklin’s crew. Key words: Franklin Expedition, skeletal remains, oxygen isotope analysis, lead poisoning, cannibalism RÉSUMÉ. En 1992, on a découvert un site non mentionné auparavant, relié à la dernière expédition de sir John Franklin (1845- 1848) dans l’île du Roi-Guillaume, située au centre de l’océan Arctique canadien. Les artefacts récupérés sur ce site comprenaient des clous en fer et en cuivre, du verre, un fragment de pipe en terre, des morceaux de tissu et de cuir de chaussure, des boutons et de multiples fragments de bois éparpillés, qui pourraient venir d’un canot de sauvetage ou d’un traîneau. -

Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism

NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut Ministère de l’Environnement Gjoa Haven © Nunavut Tourism ᐊᕙᑎᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᑦ Department of Environment Avatiliqiyikkut NUNAVUT COASTAL RESOURCE INVENTORY • Gjoa Haven INVENTORY RESOURCE COASTAL NUNAVUT Ministère de l’Environnement Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory – Gjoa Haven 2011 Department of Environment Fisheries and Sealing Division Box 1000 Station 1310 Iqaluit, Nunavut, X0A 0H0 GJOA HAVEN Inventory deliverables include: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • A final report summarizing all of the activities This report is derived from the Hamlet of Gjoa Haven undertaken as part of this project; and represents one component of the Nunavut Coastal Resource Inventory (NCRI). “Coastal inventory”, as used • Provision of the coastal resource inventory in a GIS here, refers to the collection of information on coastal database; resources and activities gained from community interviews, research, reports, maps, and other resources. This data is • Large-format resource inventory maps for the Hamlet presented in a series of maps. of Gjoa Haven, Nunavut; and Coastal resource inventories have been conducted in • Key recommendations on both the use of this study as many jurisdictions throughout Canada, notably along the well as future initiatives. Atlantic and Pacific coasts. These inventories have been used as a means of gathering reliable information on During the course of this project, Gjoa Haven was visited on coastal resources to facilitate their strategic assessment, two occasions: -

The Quest for the Northwest Passage, by James P. Delgado

REVIEWS • 323 learn the identity of what they have been reading up to that BRAY, E.F. de. 1992. A Frenchman in search of Franklin: De point. The document identified as HBCA E.37/3, which Bray’s Arctic journal, 1852–1854. Edited by William Barr. Barr, following Anderson, refers to as a full journal Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press. (p. 166, n.1), turns out to be what I would call Anderson’s PELLY, D. 1981. Expedition: An Arctic journey through history on field notes, written daily during the expedition. In con- George Back’s River. Toronto: Betelgeuse. trast, the document that Barr has referred to in footnotes as the “fair copy of Anderson’s journal” (HBCA B.200/a/ I.S. MacLaren 31), although based on those field notes, was written after Canadian Studies Program the expedition: it shows signs of revision and narrative Department of Political Science polish. Barr’s use of the term journal to refer to both University of Alberta documents is misleading, as it blurs that important distinc- Edmonton, Alberta, Canada tion. Furthermore, justification for subordinating Stewart’s T6G 2H4 journal (Provincial Archives of Alberta 74.1/137) to Anderson’s is rendered only implicitly: Stewart’s is “gen- erally less detailed than” Anderson’s (p. 166–167). One is ACROSS THE TOP OF THE WORLD: THE QUEST FOR left to infer that the editing accords with the chain of THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE. By JAMES P. DELGADO. command, Stewart being Anderson’s junior. None of these Vancouver and Toronto: Douglas & McIntyre, 1999. -

Schedule a Nunavut Land Use Plan Land Use Designations

65°W 70°W 60°W 75°W Alert ! 80°W 51 130 60°W Schedule A 136 82°N Nunavut Land Use Plan 85°W Land Use Designations 90°W 65°W Protected Area 82°N 95°W Special Management Area 135 134 80°N Existing Transportation Corridors 70°W 100°W ARCTIC 39 Proposed Transportation Corridors OCEAN 80°N Eureka ! 133 30 Administrative Boundaries 105°W 34 Area of Equal Use and Occupancy 110°W Nunavut Settlement Area Boundary 39 49 49 Inuit Owned Lands (Surface and Subsurface including minerals) 42 Inuit Owned Lands (Surface excluding minerals) 78°N 75°W 49 78°N 49 Established Parks (Land Use Plan does not apply) 168 168 168 168 168 168 49 49 168 39 168 168 168 168 168 168 39 168 49 49 49 39 42 39 39 44 168 39 39 39 22 167 37 70 22 18 Grise Fiord 44 18 168 58 58 49 ! 44 49 37 49 104 49 49 22 58 168 22 49 167 49 49 4918 76°N M 76°N 49 18 49 ' C 73 l u 49 28 167 r e 49 58 S 49 58 t r 49 58 a 58 59 i t 167 167 58 49 49 32 49 49 58 49 49 41 31 49 58 31 49 74 167 49 49 49 49 167 167 167 49 167 49 167 B a f f i n 49 49 167 32 167 167 167 B a y 49 49 49 49 32 49 32 61 Resolute 49 32 33 85 61 ! 1649 16 61 38 16 6138 74°N 74°N nd 61 S ou ter 61 nc as 61 61 La 75°W 20 61 69 49 49 49 49 14 49 167 49 20 49 61 61 49 49 49167 14 61 24 49 49 43 49 72°N 49 43 61 43 Pond Inlet 70°W 167 167 !49 ! 111 111 O Arctic Bay u t 167 167 e 49 26 r 49 49 29 L a 49 167 167 n 29 29 d 72°N 49 F 93 60 a Clyde River s 65°W 49 ! t 167 M ' C 60 49 I c l i e n 49 49 t 167 o c 72 k Z 49 o C h n 120°W a 70°N n e n 68°N 115°W e 49 l 49 Q i k i q t a n i 23 70°N 162 10 23 49 167 123 110°W 47 156 -

Mineral Exploration Projects Northwest Territories and Nunavut

_ Alert Legend Mineral Exploration Projects &% Nickel-copper PGE's Coal Northwest Territories and Nunavut *# Uranium 0 50 100 200 300 400 500 ` Kilometers Rare Earth Elements 1$ Iron /" Base Metals i[ Active Mine Canada Coal Inc. Fosheim Peninsula ?! Gold _ Eureka XY Diamonds Canada Coal Inc. _ Community Vesle Fiord Winter Road www.miningnorth.com Map Version: May 23, 2012 All Season Road NU-NWT Border _ Isachsen _ Grise Fiord _ Mould Bay _ Dundas Harbour ColtStar Ventures Inc. Eleanor /" _ Polaris Pond Inlet Resolute _ _ _ Clyde River _ Nanisivik _ Commander Resources Ltd. Arctic Bay Storm /" Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation ColtStar Ventures Inc. Mary River _ Qikiqtarjuaq Allen Bay Copper /" 1$ Rio Tinto Canada Exploration Inc. Banks Island Commander Resources Ltd. XY Bravo Lake (Baffin Island Gold) ?! Peregrine Diamonds Ltd. ?! Cumberland Commander Resources Ltd. _ Johnson Point Qimmiq (Baffin Island Gold) XY Fort Ross _ _ Pangnirtung _ Sachs Harbour _ Igloolik Stornoway Diamond Corporation Aviat XY _ Hall Beach Peregrine Diamonds Ltd. Advanced Exploration Inc. 1$ Chidliak Tuktu XY Advanced Exploration Inc. Peregrine Diamonds Ltd. Ulukhaktok 1$ Roche Bay Qilaq _ Advanced Exploration Inc. Tuktoyaktuk Diamonds North Resources Ltd. Western Permits _ _ Cape Parry Halkett Inlet Gold XY _ /" Taloyoak ?! West Melville Iron Company Ltd. Fraser Bay Deposit Vale Canada Limited 1$ Melville Permits /" _ Iqaluit Kugaaruk Darnley Bay Resources Ltd. _ Darnley Bay Diamonds North Resources Ltd. _ Aklavik Diamonds North Resources Ltd. Barrow _ Inuvik _ &% Amaruk XY Paulatuk MMG Resources Inc. &%XY Diamonds North Resources Ltd. Amaruk Nickel ?! Amaruk Gold _ _ Cambridge Bay Gjoa Haven _ Kimmirut _ Fort McPherson Stornoway Diamond Corporation ?! Qilalugaq _ Tsiigehtchic Talmora Diamond Inc. -

An Overview of the Hudson Bay Marine Ecosystem

10–1 10.0 BIRDS Chapter Contents 10.1 F. GAVIIDAE: Loons .............................................................................................................................................10–2 10.2 F. PODICIPEDIDAE: Grebes ................................................................................................................................10–3 10.3 F. PROCELLARIIDAE: Fulmars...........................................................................................................................10–3 10.4 F. HYDROBATIDAE: Storm-petrels......................................................................................................................10–3 10.5 F. PELECANIDAE: Pelicans .................................................................................................................................10–3 10.6 F. SULIDAE: Gannets ...........................................................................................................................................10–4 10.7 F. PHALACROCORACIDAE: Cormorants............................................................................................................10–4 10.8 F. ARDEIDAE: Herons and Bitterns......................................................................................................................10–4 10.9 F. ANATIDAE: Geese, Swans, and Ducks ...........................................................................................................10–4 10.9.1 Geese............................................................................................................................................................10–5