Confederate Symbols: Relation to Federal Lands and Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

161 F.Supp.2D 14

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA NATIONAL COALITION TO SAVE OUR MALL, et al., Plaintiffs, v. Civil Action 00-2371 (HHK) GALE NORTON, Secretary of the Interior, et al., Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION On May 25, 1993, Congress authorized the construction of a memorial in the District of Columbia to honor members of the Armed Forces who served during World War II and to commemorate the United States’ participation in that war. See Pub. L. 103-32, 107 Stat. 90, 91 (1993). The act empowered the American Battle Monuments Commission (“ABMC”), in connection with a newly-created World War II Memorial Advisory Board, to select a location for the WWII Memorial, develop its design, and raise private funds to support its construction. On October 25, 1994, Congress approved the location of the WWII Memorial in “Area 1” of the District, which generally encompasses the National Mall and adjacent federal land. See Pub. L. 103-422, 108 Stat. 4356 (1994). The ABMC reviewed seven potential sites within Area I and endorsed the Rainbow Pool site at the east end of the Reflecting Pool between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument as the final location for the WWII Memorial.1 Finally, 1 Out of the seven sites examined, the ABMC originally selected the Constitution Gardens area (between Constitution Avenue and the Rainbow Pool) as the location for the WWII Memorial, but later decided to endorse the present Rainbow Pool site. in May, 2001, Congress passed new legislation directing the expeditious construction of the WWII Memorial at the selected Rainbow Pool site. -

The George Wright Forum

The George Wright Forum The GWS Journal of Parks, Protected Areas & Cultural Sites volume 34 number 3 • 2017 Society News, Notes & Mail • 243 Announcing the Richard West Sellars Fund for the Forum Jennifer Palmer • 245 Letter from Woodstock Values We Hold Dear Rolf Diamant • 247 Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage Rebecca Conard and John H. Sprinkle, Jr., guest editors Dedication•252 Planned Obsolescence: Maintenance of the National Park Service’s History Infrastructure John H. Sprinkle, Jr. • 254 Shining Light on Civil War Battlefield Preservation and Interpretation: From the “Dark Ages” to the Present at Stones River National Battlefield Angela Sirna • 261 Farming in the Sweet Spot: Integrating Interpretation, Preservation, and Food Production at National Parks Cathy Stanton • 275 The Changing Cape: Using History to Engage Coastal Residents in Community Conversations about Climate Change David Glassberg • 285 Interpreting the Contributions of Chinese Immigrants in Yosemite National Park’s History Yenyen F. Chan • 299 Nānā I Ke Kumu (Look to the Source) M. Melia Lane-Kamahele • 308 A Perilous View Shelton Johnson • 315 (continued) Civic Engagement, Shared Authority, and Intellectual Courage (cont’d) Some Challenges of Preserving and Exhibiting the African American Experience: Reflections on Working with the National Park Service and the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site Pero Gaglo Dagbovie • 323 Exploring American Places with the Discovery Journal: A Guide to Co-Creating Meaningful Interpretation Katie Crawford-Lackey and Barbara Little • 335 Indigenous Cultural Landscapes: A 21st-Century Landscape-scale Conservation and Stewardship Framework Deanna Beacham, Suzanne Copping, John Reynolds, and Carolyn Black • 343 A Framework for Understanding Off-trail Trampling Impacts in Mountain Environments Ross Martin and David R. -

The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B

Welcome to a free reading from Washington History: Magazine of the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. As we chose this week’s reading, news stories continued to swirl about commemorative statues, plaques, street names, and institutional names that amplify white supremacy in America and in DC. We note, as the Historical Society fulfills its mission of offering thoughtful, researched context for today’s issues, that a key influence on the history of commemoration has come to the surface: the quiet, ladylike (in the anachronistic sense) role of promoters of the southern “Lost Cause” school of Civil War interpretation. Historian Michael Chornesky details how federal officials fended off southern supremacists (posing as preservationists) on how to interpret Arlington House, home of George Washington’s adopted family and eventually of Confederate commander Robert E. Lee. “Confederate Island upon the Union’s ‘Most Hallowed Ground’: The Battle to Interpret Arlington House, 1921–1937,” by Michael B. Chornesky. “Confederate Island” first appeared in Washington History 27-1 (spring 2015), © Historical Society of Washington, D.C. Access via JSTOR* to the entire run of Washington History and its predecessor, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, is a benefit of membership in the Historical Society of Washington, D.C. at the Membership Plus level. Copies of this and many other back issues of Washington History magazine are available for browsing and purchase online through the DC History Center Store: https://dchistory.z2systems.com/np/clients/dchistory/giftstore.jsp ABOUT THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON, D.C. The Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is a non-profit, 501(c)(3), community-supported educational and research organization that collects, interprets, and shares the history of our nation's capital in order to promote a sense of identity, place and pride in our city and preserve its heritage for future generations. -

United Confederate Veterans Association Records

UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS (Mss. 1357) Inventory Compiled by Luana Henderson 1996 Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana Revised 2009 UNITED CONFEDERATE VETERANS ASSOCIATION RECORDS Mss. 1357 1861-1944 Special Collections, LSU Libraries CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF SUBGROUPS AND SERIES ......................................................................................... 7 SUBGROUPS AND SERIES DESCRIPTIONS ............................................................................ 8 INDEX TERMS ............................................................................................................................ 13 CONTAINER LIST ...................................................................................................................... 15 APPENDIX A ............................................................................................................................... 22 APPENDIX B ............................................................................................................................. -

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür Ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol. 9, No. 3, September 2020 DOI: 10.7596/taksad.v9i3.2768 Citation: Borysovych, O. V., Chaiuk, T. A., & Karpova, K. S. (2020). Black Lives Matter: Race Discourse and the Semiotics of History Reconstruction. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 9(3), 325- 340. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v9i3.2768 Black Lives Matter: Race Discourse and the Semiotics of History Reconstruction Oksana V. Borysovych1, Tetyana A. Chaiuk2, Kateryna S. Karpova3 Abstract The death of unarmed black male George Floyd, who was killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis, May 25, 2020, has given momentum to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement whose activists rallied in different parts of the world to remove or deface monuments to historic figures associated with racism, slavery, and colonialism. These social practices of toppling statues have a discursive value and, since they are meant to communicate a message to the broader society, these actions are incorporated into a semiotic system. This study examines signs and, therefore, the system of representations involved in toppling statues performed by BLM activists and documented in photos. The research employs a critical approach to semiotics based on Roland Barthes’ (1964) semiotic model of levels of signification. However, for a comprehensive analytical understanding, the study also makes use of a multidisciplinary Critical Discourse Analysis CDA approach which provides a systematic method to examine and expose power relations, inequality, dominance, and oppression in social practices. Besides its general analytical framework, the integrated CDA approach combines Fairclough’s (1995) three-dimensional analytical approach, which presupposes examining text, discursive practice, and sociocultural practice, with Reisigl and Wodak’s (2001, 2017) Discourse Historical Analysis (DHA), which investigates ideology and racism within their socio-cultural and historic context. -

Follow in Lincoln's Footsteps in Virginia

FOLLOW IN LINCOLN’S FOOTSTEPS IN VIRGINIA A 5 Day tour of Virginia that follows in Lincoln’s footsteps as he traveled through Central Virginia. Day One • Begin your journey at the Winchester-Frederick County Visitor Center housing the Civil War Orientation Center for the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Become familiar with the onsite interpretations that walk visitors through the stages of the local battles. • Travel to Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters. Located in a quiet residential area, this Victorian house is where Jackson spent the winter of 1861-62 and planned his famous Valley Campaign. • Enjoy lunch at The Wayside Inn – serving travelers since 1797, meals are served in eight antique filled rooms and feature authentic Colonial favorites. During the Civil War, soldiers from both the North and South frequented the Wayside Inn in search of refuge and friendship. Serving both sides in this devastating conflict, the Inn offered comfort to all who came and thus was spared the ravages of the war, even though Stonewall Jackson’s famous Valley Campaign swept past only a few miles away. • Tour Belle Grove Plantation. Civil War activity here culminated in the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19, 1864 when Gen. Sheridan’s counterattack ended the Valley Campaign in favor of the Northern forces. The mansion served as Union headquarters. • Continue to Lexington where we’ll overnight and enjoy dinner in a local restaurant. Day Two • Meet our guide in Lexington and tour the Virginia Military Institute (VMI). The VMI Museum presents a history of the Institute and the nation as told through the lives and services of VMI Alumni and faculty. -

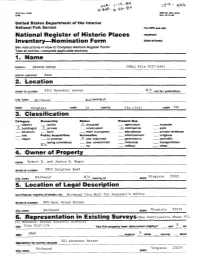

Nomination Form Date Entered See Instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type All Entries-Complete Applicable Sections 1

OM6 No.1024-0018 Erp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name hlstortc BRANCH HOUSE (VHLC File 6127-246) -- ----- - - and or common Same 2. Location 8 number 2501 Monument Avenue - N/Anot for publication city, town Richmond Fk4\ vicinity of stale Virginia code 5 1 county (in city) code 750 3.- Classification- - ~~ Category Ownership Status Present Use -district -public X occupied agriculture -museum X building@) X private unoccupied _.X_ commercial - _park -structure -both -work in progress -educational -private residence -site Public Acquisition Accessible -entertainment -.religious -object - in process x yes: restricted -governmani -scientific being considered yes: unrestricted -industrial -transportation TA -no -military -other: 4. Owner of Property name Robert E. and Janice W. Pogue street & number 3902 Sulgrave Ibad Virginia 23221 city, town N/Avicinity of state -- -- 5. Location of Leaal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Richmond City Hall Tax Assessor's Off ice street & number 900 East Broad Street - city, town Richmond state Virginia 23219 6. Representation in Existing $urveys(see continuation Sheet iil) (I) Monument Avenue HlstOrlc ulstrlct titleFile 11127-174 has this properly been determined eligible? -yes -noX - X 1969 -federal slate county .- local date ---- - --.-- 221 Governor Street depository for survey records -- - -. -- - - - Richmond Virginia 23219 state city, town -- . - 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _X excellent -deteriorated & unaltered -L original site -good -ruins -altered -moved date -..-.___--p-N/ A A fair -unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance SUMMARY DESCRIPTION The Branch House at 2501 Monument Avenue is situated on the southeast corner of Monument Avenue and Davis Street in the Fan District of Richmond. -

Human Rights, Collective Memory, and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia Melanie L

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Art Education Publications Dept. of Art Education 2011 Human Rights, Collective Memory, and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia Melanie L. Buffington Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Erin Waldner Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs Part of the Art Education Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Copyright © 2011 Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/arte_pubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Dept. of Art Education at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Education Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Human Rights, Collective Memory,' and Counter Memory: Unpacking the Meaning of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia M ELANIE L. BUFFI" GTO'l ' ''D ERI" W ALD " ER ABSTRACT Th is article addresses human rights issues of the built environment via the presence of monuments in publi c places. Because of their prominence, monuments and publi c art can offer teachers and students many opportunit ies for interdiscip li nary study that directly relates to the history of their location Through an exploration of the ideas of co llective memory and counter memory, t his articl e explores the spec ific example of Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia, Further; the aut hors investigate differences in t he ways monu ments may be understood at the time they were erected versus how they are understood in the present. -

The Flag to Fly No More? Confederate References 1889 and Marks Where 800 Come Under Fire After Residents Volunteered to Join S.C

Vol. 11, No. 29 Alexandria’s only independent hometown newspaper JULY 16, 2015 The flag to fly no more? Confederate references 1889 and marks where 800 come under fire after residents volunteered to join S.C. shooting the Army of Northern Vir- BY ERICH WAGNER ginia. And a plaque adorns As one of the biggest the Marshall House — now state-sanctioned reminders Hotel Monaco — at the corner of the U.S. Civil War — of King and South Pitt streets, the Confederate battle flag commemorating where hotel — was removed from the owner James W. Jackson shot grounds of South Carolina’s and killed Union Col. Elmer E. PHOTO/GEOFF LIVINGSTON 266 YEARS YOUNG The Potomac River is lit up by fireworks capitol last week, the debate Ellsworth before being shot by at the conclusion of Alexandria’s 266th birthday celebrations and over references to southern other Union troops during their the United States’ 239th birthday last weekend. The evening’s secession in Alexandria was takeover of the city. event at Oronoco Bay Park saw Mayor Bill Euille and city coun- cilors distribute birthday cake before the Alexandria Symphony just heating up. Lance Mallamo, director of Orchestra performed, among other highlights. The shooting deaths of the Office of Historic Alexan- nine people at a Bible study dria, said the idea for the Ap- meeting at a historic black pomattox statue came from Ed- church in Charleston, S.C. last gar Warfield, the last surviving Shots fired calls in month has caused an ground- member of the group, in 1885. swell in discussions about the “After the war, he came back prominence of the Confed- to Alexandria and became a Alexandria down erate flag across the South. -

The Shadow of Napoleon Upon Lee at Gettysburg

Papers of the 2017 Gettysburg National Military Park Seminar The Shadow of Napoleon upon Lee at Gettysburg Charles Teague Every general commanding an army hopes to win the next battle. Some will dream that they might accomplish a decisive victory, and in this Robert E. Lee was no different. By the late spring of 1863 he already had notable successes in battlefield trials. But now, over two years into a devastating war, he was looking to destroy the military force that would again oppose him, thereby assuring an end to the war to the benefit of the Confederate States of America. In the late spring of 1863 he embarked upon an audacious plan that necessitated a huge vulnerability: uncovering the capital city of Richmond. His speculation, which proved prescient, was that the Union army that lay between the two capitals would be directed to pursue and block him as he advanced north Robert E. Lee, 1865 (LOC) of the Potomac River. He would thereby draw it out of entrenched defensive positions held along the Rappahannock River and into the open, stretched out by marching. He expected that force to risk a battle against his Army of Northern Virginia, one that could bring a Federal defeat such that the cities of Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Washington might succumb, morale in the North to continue the war would plummet, and the South could achieve its true independence. One of Lee’s major generals would later explain that Lee told him in the march to battle of his goal to destroy the Union army. -

Nominees and Bios

Nominees for the Virginia Emancipation Memorial Pre‐Emancipation Period 1. Emanuel Driggus, fl. 1645–1685 Northampton Co. Enslaved man who secured his freedom and that of his family members Derived from DVB entry: http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Driggus_Emanuel Emanuel Driggus (fl. 1645–1685), an enslaved man who secured freedom for himself and several members of his family exemplified the possibilities and the limitations that free blacks encountered in seventeenth‐century Virginia. His name appears in the records of Northampton County between 1645 and 1685. He might have been the Emanuel mentioned in 1640 as a runaway. The date and place of his birth are not known, nor are the date and circumstances of his arrival in Virginia. His name, possibly a corruption of a Portuguese surname occasionally spelled Rodriggus or Roddriggues, suggests that he was either from Africa (perhaps Angola) or from one of the Caribbean islands served by Portuguese slave traders. His first name was also sometimes spelled Manuell. Driggus's Iberian name and the aptitude that he displayed maneuvering within the Virginia legal system suggest that he grew up in the ebb and flow of people, goods, and cultures around the Atlantic littoral and that he learned to navigate to his own advantage. 2. James Lafayette, ca. 1748–1830 New Kent County Revolutionary War spy emancipated by the House of Delegates Derived from DVB/ EV entry: http://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Lafayette_James_ca_1748‐1830 James Lafayette was a spy during the American Revolution (1775–1783). Born a slave about 1748, he was a body servant for his owner, William Armistead, of New Kent County, in the spring of 1781. -

Chapter 1: National Memorials Ordinance 1928

4 The New Model 4.1 While the evidence presented to the JSCNCET raises valid arguments for the reform of the CNMC, the Committee argues that the CNMC and the Ordinance should be abolished. The membership of the CNMC as currently constituted is not effective and any reforms are unlikely to make its operation more effective. A number of submissions have highlighted the problems of involving senior parliamentarians in the approvals process, and the high risk of bureaucratic capture, under the current Ordinance. 4.2 On the other hand, the Washington model provides a framework for direct legislative involvement, expert management and effective public consultation. The Washington Model 4.3 Washington DC shares with Canberra the attributes of being both a national capital and a planned city. As an expression of national aspirations in itself, and a site for commemoration of the nation’s history, Washington, like Canberra, is subject to a detailed planning regime which must balance the legacy of the past with the requirements of the present and the possibilities of the future. Part of this is dealing with the challenge of choosing appropriate subjects for commemoration and choosing suitable designs and locations for new monuments and memorials. 4.4 The Commemorative Works Act 1986 specifies requirements for the development, approval, and location of new memorials and monuments in the District of Columbia and its environs. The Act preserves the urban design legacy of the historic L’Enfant and McMillan Plans by protecting public open space and ensuring that future memorials and monuments in 56 ETCHED IN STONE? areas administered by the National Park Service and the General Services Administration are appropriately located and designed.