Note to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asian Heritage Month Report

ASIANASIAN HHERITAGEERITAGE MMONTHONTH REPORTREPORT 20172017 www.asianheritagemanitoba.comwww.asianheritagemanitoba.com TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 ASIAN HERITAGE MONTH OPENING CEREMONY ................................................................................................................................... 5 ASIAN WRITERS’ SHOWCASE ................................................................................................................................................................. 9 ASIAN CANADIAN DIVERSITY FESTIVAL ................................................................................................................................................ 11 ASIAN HERITAGE HIGH SCHOOL SYMPOSIUM ..................................................................................................................................... 13 ASIAN FILM NIGHT REPORT ................................................................................................................................................................. 19 ASIAN CANADIAN FESTIVAL ................................................................................................................................................................. 23 ASIAN HERITAGE MONTH CLOSING CEREMONIES .............................................................................................................................. -

To Download the PDF File

Publics in the Making: A Genealogical Inquiry into the Discursive Publics of Japanese Canadian Redress by Jennifer Matsunaga A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2011, Jennifer Matsunaga Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre re'terence ISBN: 978-0-494-83084-0 Our file Notre rSterence ISBN: 978-0-494-83084-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Brockseneca (Page 1)

FirstClass® User Profile Educators Get Together in FirstClass Online Conferences The new venture partners Brock University with the Ontario Colleges of Applied Arts and Technology (CAATs) — most prominently with Seneca College — and with TVOntario (TVO), the province's educational television network. Led by Seneca's Centre for Teaching and Learning, the joint committee developed a Bachelor of Education in Adult Education (BEd in AE) Degree Program and a Certificate in Adult Education Program, designed around core courses in the foundations of adult learning, curriculum theory and design, and instructional strategies. Both the degree and the certificate are offered as distance education programs, presented at a community college location. The initiative is primarily an outreach program for MR. FIRSTCLASS community college faculty and staff as well as for private industry trainers across the country. It also involves Darrell Nunn, an creative collaboration with TVO to develop a distance instructor at Seneca learning model using videos. The courses are designed by College, in Toronto, professors in the Faculty of Education at Brock University Canada, is a vocal champion of online and delivered on 22 campuses across the province by on- collaborative site facilitators from Brock and community colleges. Print learning. He has materials are used, along with TVO's videotapes, which taught more students and more diverse subjects using feature expert guests as well as the zany talents of FirstClass Intranet Server — an integrated Toronto's Second City Comedy Troupe. Adult educators collaboration/communication groupware solution from — many of whom work in business and industry — are MC2 — than any of his colleagues at Canada's largest enthusiastic about this new way of learning. -

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People”

Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015 “Japan and Canada in Comparative Perspective: Economics and Politics; Regions, Places and People” A Collection of Papers from an International Conference held in Tokyo, May 2015, organized jointly by the Japan Studies Association of Canada (JSAC), the Japanese Association for Canadian Studies (JACS) and the Japan-Canada Interdisciplinary Research Network on Gender, Diversity and Tohoku Reconstruction (JCIRN). Edited by David W. Edgington (University of British Columbia), Norio Ota (York University), Nobuyuki Sato (Chuo University), and Jackie F. Steele (University of Tokyo) © 2016 Japan Studies Association of Canada 1 Table of Contents List of Tables................................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 List of Contributors ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Editors’ Preface ............................................................................................................................................. 7 SECTION A: ECONOMICS AND POLITICS IN JAPAN .......................................................................... -

Association of Architecture School Librarians 2015 Annual Conference

Association of Architecture School Librarians 2015 Annual Conference Report Prepared by Jen Wong, Director, Materials Lab School of Architecture, The University of Texas at Austin 2015 Recipient of the Frances Chen AASL Conference Travel Award The 2015 annual conference of the Association of Architecture School Librarians was held in Toronto, Ontario, for the first time since its inaugural meeting thirty-seven years ago. The conference was held in the center of downtown at the Sheraton Centre Toronto from March 17 through March 19, with forty-eight representatives from forty institutions in attendance. Among the attendees were architecture, art, engineering, planning, and fashion librarians, professors of architecture, archivists, catalogers, directors of visual resource and materials collections, and representatives of print and online publications. The weather was gorgeous for the duration of the conference – bright and brisk – and our Toronto-based hosts did a wonderful job of showing us their city. As in the past, the 2015 conference program offered a balance of activities that included presentations, tours, and opportunities for networking. The conference kicked off Tuesday morning with a brunch featuring guest speaker Shawn Micallef, recent author of The Trouble with Brunch: Work, Class, and the Pursuit of Leisure. Micallef gave a lighthearted talk about Toronto, his adopted home, introducing projects that have sought to understand or explain the city’s development in a meaningful way through unconventional means. His talk was followed by a presentation by Cindy Derrenbacker of Laurentian University, who introduced the life and work of Toronto-based architect Raymond Moriyama. The presentation provided a knowledge base that was useful in understanding many of the projects visited during the conference, including the Bata Shoe Museum, the Toronto Reference Library, and the Aga Khan Museum – significant, landmark buildings designed by his firm Moriyama & Teshima Architects. -

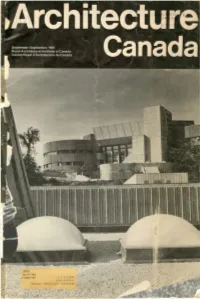

RAIC Vol46 No09 Access.Pdf (10.86Mb)

S N A"riJ11l'fH 1caa s11<Pas ' IN BRIEF Prus wins RCAF Competition TRENTON In awarding first prize of $23,500 to Montreal architect Victor Prus, the jury for the RCAF Memorial Architectural Competition said they found "A scheme of profound clarity and simplicity which succeeded in making all aspects of the Memorial contribute to the vitality and pleasure of the whole." (See also page 5) Competition for Regina City Hall This is the age of concrete-and PORZITE REGINA The city will hold a national competition for the design of makes it better a new city hall. E. H. Grolle, SAA Past The ability to translate imaginative design into lasting performance has President, heads an Association com made concrete a favorite building medium in modern architecture. Porzite mjttee advising the city on the propos water reducing concrete admixtures improve the workability, strength and al. Morley Blankstein FRAIC, Win cohesiveness needed to produce the best possible results. Whatever the nipeg, is professional adviser. Council engineering problem, bridges to buildings, complex or routine, when pre sold its old city hall site for $621,000 dictable concrete performance is demanded- Porzite supplies the answer. for the Midtown Shopping Centre This includes hundreds of component units in the pre-cast, pre-stressed and diwelopment in 1965 and bought the post-stressed field of manufacture. Henry Grolle, MRAIC 63-year-old federal post office for The increasing trend toward the greater use of concrete in Canada is aptly $100,000 for interim use as a civic displayed, in the Arts Building of the University of Guelph (above). -

The Joint Venture of Moriyama & Teshima Architects of Toronto

Architects The joint venture of Moriyama & Teshima Architects of Toronto and Griffiths Rankin Cook Architects of Ottawa was formed to design the New Canadian War Museum. Raymond Moriyama and Alexander Rankin, partners of the two firms, had known each other for many years and were looking for a suitable project on which they could collaborate. This significant national project was a golden opportunity. Over the last two years incredible progress has been made in design and construction thanks to the client and, in particular, Joe Geurts, Director and CEO of the Canadian War Museum, the project manager, construction manager, contractors, all the workers, the National Capital Commission, the consultants, and our staff. The structure has been received with great enthusiasm and excitement, especially from the construction workers and, of course, the veterans. For the architects and the whole team, hearing this kind of excitement for a project is rare and very inspiring. Raymond Moriyama, with the assistance of Alexander Rankin, is leading the overall team. With over 70 people in the two firms, the joint venture has dedicated considerable resources to the project. The combined team includes Diarmuid Nash, Alex Leung, Earl Reinke, among many others. Our team of on-site staff is working closely with the construction team, often on a minute-to-minute basis, to enable quality construction of all the details in this challenging design of angled walls and three-dimensional junctions. An extensive multi-disciplinary team has been working with the joint venture to make the project a success, including many specialist consultants and engineers, especially Adjeleian Allen Rubeli, the structural engineer, The Mitchell Partnership, the mechanical engineer, and Crossey Engineering, the electrical engineer. -

The Canadian Japanese, Redress, and the Power of Archives R.L

The Canadian Japanese, Redress, and the Power of Archives R.L. Gabrielle Nishiguchi (Library and Archives Canada) [Originally entitled: From the Shadows of the Second World War: Archives, Records and Cana- dian Japanese]1 I am a government records archivist at Library and Archives Canada2 who practises macro- appraisal. It should be noted that the ideas of former President of the Bundesarchiv, Hans Booms3, inspired Canadian Terry Cook, the father of macro-appraisal -which has been the appraisal approach of my institution since 1991. “If there is indeed anything or anyone qualified to lend legitimacy to archival appraisal,” Hans Booms wrote in 1972, ‘it is society itself….”4 As Cook asserts, Booms was “perhaps the first 1 This Paper was delivered on 15 October 2019 at the Conference: “Kriegsfolgenarchivgut: Entschädigung, Lasten- ausgleich und Wiedergutmachung in Archivierung und Forschung” hosted by the Bundesarchiv, at the Bundesar- chiv-Lastenausgleichsarchiv, Bayreuth, Germany. The views, thoughts and opinions expressed in this paper belong solely to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Library and Archives Canada. 2 Library and Archives Canada had its beginnings in 1872 as the Archives Branch of the Department of Agriculture. In 1903, the Archives absorbed the Records Branch of the Department of the Secretary of State. It was recognized by statute as the Public Archives of Canada in 1912 and continued under this name until 1987 when it became the National Archives of Canada as per the National Archives of Canada Act, R.S.C. , 1985, c. 1 (3rd Supp.), accessed 10 January 2020. In 2004, the National Archives of Canada and the National Library of Canada. -

THE ASAHI BASEBALL TEAM REMEMBERED Introduction

THE ASAHI BASEBALL TEAM REMEMBERED YV Introduction The Asahi Internment Focus Asahi in Japanese means “morning In September 1939 the Second World The Asahi Baseball Club, a group of sun.” Five young Japanese men, four War erupted. Canada declared war on Japanese Canadian Issei and one Nisei, formed the first Germany. The Asahi continued to play baseball players Asahi baseball team in Vancouver, baseball and, for five consecutive years, who were interned B.C., in 1914. The Nisei loved the game defeated their competitors and won the during the Second because it was such a big part of North prized Northwest Pacific Champion- World War, is remembered today American culture and it was affordable ship. When Japan entered the war in for victories on the for working-class families. Some 1941 there was no warning that the baseball diamond parents had even played the game in Canadian government would soon in the face of Japan. Young players formed teams announce that all Japanese Canadians discrimination and under the Asahi organization. The were “enemy aliens” in their own racist attitudes. This youngest team was called the Clovers, country. Yet early in 1942, just after the News in Review report examines the next team was the Beavers, and the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in the treatment of oldest and most advanced team was December 1941, 22 000 Japanese Japanese Canadians known as the Athletics. The Asahi Club Canadians were relocated to internment leading up to 1939, drew their players mostly from Little and labour camps. The Asahi Baseball their internment Tokyo in Vancouver, and played at Club was disbanded and never played during the Second World War, and the Athletic Park and Powell Grounds. -

Welcome Guide >>>

Welcome Guide >>> Welcome Guide For Exchange and International Students This Guide will be used by both International Degree Seeking Students at Schulich in addition to Exchange Students studying at Schulich for one or two terms. Some information included will only pertain to one group of students and will be noted: International Degree seeking students will be referred to as “International students” Exchange students will be differentiated as “Exchange Students” Undergraduate students (BBA, iBBA) will be identified as “Undergraduate or UG” Graduate students (MBA, iMBA) will be differentiated as “Graduate or GR” Schulich School of Business York University 4700 Keele Street Toronto, Ontario Canada M3J 1P3 Phone: 416-736-5059 Fax: 416-650-8174 E-mail (Exchange): [email protected] E-mail (International): [email protected] 1 Welcome Guide >>> Table of Contents Student Services & International Relations 5 1 Before You Leave Home Your Visa Status 6 Length of Stay Country of Citizenship Other Activities Family Member Requirements Procedures Arriving at a Port of Entry 7 Immigration Check Canada Customs Information for International Students Plan Your Arrival in Toronto Packing Checklist 8 Plan for Student Life 9 Financial Planning Tuition Fee and Living Expenses Transferring Funds Plan for Canadian Weather 2 Living in Toronto Toronto 12 Quick Facts Moving Around in Toronto 13 Toronto Transit Commission Other Transportation Services Shopping in Toronto 14 Groceries Household Goods and Clothing Toronto Attractions 18 -

Li Xiaodong of China Wins the First $100,000 Moriyama RAIC International Prize

Li Xiaodong of China wins the first $100,000 Moriyama RAIC International Prize TORONTO, October 11, 2014 — A modest library on the outskirts of Beijing, China, designed by architect Li Xiaodong, has won the inaugural Moriyama RAIC International Prize. Distinguished Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama, FRAIC, established the prize in collaboration with the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) and the RAIC Foundation. It includes a monetary award of CAD$100,000 and a crystal sculpture by Canadian designer Wei Yew. Download project images and video here Download press kit here The prize was presented on Saturday evening at a gala attended by 350 guests in the new Aga Khan Museum in Toronto. One of the most generous architectural prizes in the world, the Moriyama RAIC International Prize is awarded to a building that is judged to be transformative, inspired as well as inspiring, and emblematic of the human values of respect and inclusiveness. It is open to all architects, irrespective of nationality and location. It recognizes a single work of architecture, as opposed to a life’s work, and celebrates buildings in use. The RAIC received submissions for projects located in nine countries: Canada, China, France, Germany, Israel, Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and Tajikistan. The jury was impressed by the breadth of international interest in the prize and encouraged by the high level of engagement with the aims and objectives of the program revealed in the submissions. “They represent works across a wide spectrum of architecture around the world today – from the object building that purports to change everything and everyone it serves, to some self-effacing projects that quietly look at the world with optimism and humility,” said Barry Johns, FRAIC, Chancellor of the RAIC College of Fellows and Chair of the Jury. -

Source 4.12 a Post-War History of Japanese Canadians

LESSON 4 SOURCE 4.12 A POST-WAR HISTORY OF JAPANESE CANADIANS With World War II winding down, the Canadian government started In 1947, the government agreed to an investigation into Japanese planning for the future of Japanese Canadians. In the United States of Canadian property loss when it could be demonstrated that properties America, incarcerated Japanese Americans won a December 1944 were not sold at “fair market value” (Politics of Racism, p. 147). Supreme Court decision which ruled that though the wartime internment Cabinet wanted to keep the investigation limited in scope and cost, of Japanese Americans was constitutional, it ruled in a separate decision and managed to have it limited to cases where the Custodian had not that loyal citizens must be released. Japanese Americans started disposed of the property near market value. Justice Henry Bird was returning to their homes on the coast in January 1945. appointed to represent the government in the Royal Commission of In January 1945, Japanese Canadians were forced by the Canadian Japanese Canadian Losses. He tried to dispense with hearings in government to choose between “repatriation” (exile) to Japan or order to streamline claims. Justice Bird concluded his investigation in “dispersal” east of the Rocky Mountains. 10,632 people signed up for April 1950. He announced that the Custodian performed his job deportation to Japan, however, more than half later rescinded their competently. He also reported that sometimes properties were not sold signatures. In the end almost 4,000 were deported to Japan. Japanese at a fair market value. Canadians who wished to remain in Canada could not return to B.C.