Lessons from the Pivot: Higher Education's Response to the Pandemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

PAPER TIGERS Adverse Childhood Experience TABLE of CONTENTS Faith Leaders Guide

FAITH LEADERS GUIDE PAPER TIGERS Adverse Childhood Experience TABLE OF CONTENTS Faith Leaders Guide HIGHLIGHTED INSIDE THIS GUIDE, WE HAVE SHARED: 1. The Role of Faith in a Global Society where humans long for meaning and hope, healing and understanding. 2. Understanding ACEs in potentially traumatic events that can have negative, lasting effects on health and well-being. 3. How Faith Communities Can Help through understanding ACEs and provide trauma-informed counseling, services and referrals. 4. Viewing Paper Tigers and discussing ACEs, which includes Five Steps to Viewing the Film. 5. "A Prayer for The Children," by Rev. Dr. Keith Magee 6. A Social Media Guide, with suggested posts to share with your online community. violence, or living with someone with a mental illness—massively increases the risk of problems WELCOME in adulthood. Problems like addiction, suicide and even heart disease have their roots in childhood Greetings Friends, experience. Thank you for your willingness to become engaged Many individuals find comfort and assistance from with Paper Tigers and learn more about Adverse spiritual leaders and faith communities during Childhood Experiences (ACEs). times of trauma. In fact, many people turn to faith communities for support before they turn to mental Our world, indeed all of creation, is longing for health professionals. For some, religious beliefs and healing. Throughout the world, throughout history, faith provide a source of wisdom or a narrative that CONTENTS and even more so today, people are longing for a can help re-establish a sense of meaning after a Faith Leaders Guide life with dignity in just and sustainable communities. -

Hjc Minimum Advertised Price Policy 1 Effective June 1, 2021

HJC MINIMUM ADVERTISED PRICE POLICY 1 EFFECTIVE JUNE 1, 2021 FULL FACE HELMETS MODEL MSRP (USD) RPHA 11 PRO SOLID $399.99 RPHA 11 PRO MATTE/ METALLIC $409.99 RPHA 11 PRO CRUTCHLOW BLACK $549.99 RPHA 11 PRO CRUTCHLOW STREAMLINE $549.99 RPHA 11 PRO SUPERMAN DC COMICS $599.99 RPHA 11 PRO JOKER DC COMICS $599.99 RPHA 11 PRO CARNAGE MARVEL $599.99 RPHA 11 PRO VENOM 2 MARVEL $599.99 RPHA 11 PRO ALIENS (FOX) $599.99 RPHA 11 PRO OTTO (MINIONS) $599.99 RPHA 11 PRO JARBAN $449.99 RPHA 11 PRO STOBAN $449.99 RPHA 11 PRO NECTUS $449.99 RPHA 11 PRO FESK $449.99 RPHA 11 PRO BINE $449.99 RPHA 11 CARBON $579.99 RPHA 11 CARBON NAKRI $649.99 RPHA 11 CARBON BLEER $619.99 RPHA 70 ST SOLID $399.99 RPHA 70 ST MATTE/ METALLIC $409.99 RPHA 70 ST KOSIS $449.99 RPHA 70 ST WODY $449.99 RPHA 70 ST SAMPRA $449.99 RPHA 70 ST SHUKY $449.99 RPHA 70 CARBON $579.99 RPHA 70 CARBON ARTAN $619.99 RPHA 70 CARBON REPLE $619.99 F70 SOLID $279.99 F70 MATTE/METALLIC $284.99 F70 STONE GREY $289.99 F70 DEATH STROKE (DC COMICS) $399.99 F70 TINO $319.99 F70 FERON $319.99 F70 MAGO $319.99 F70 CARBON $429.99 F70 CARBON ESTON $469.99 I70 SOLID $199.99 I70 MATTE/METALLIC $204.99 I70 REDEN $229.99 I70 WATU $229.99 I70 ELUMA $229.99 I70 BANE (DC COMICS) $299.99 I10 SOLID $149.99 I10 MATTE/METALLIC $154.99 I10 MAZE $179.99 I10 TAZE $179.99 CL-17 SOLID PLUS (3XL-5XL ONLY) $139.99 CL-17 MATTE PLUS (3XL-5XL ONLY) $144.99 C70 SOLID $149.99 C70 MATTE/METALLIC $154.99 C70 EURA $179.99 C70 KORO $179.99 CSR3 SOLID $99.99 CSR3 MATTE/METALLIC $104.99 CSR3 MYLO $119.99 CSR3 DOSTA $119.99 CSR3 NAVIYA -

Finn Academy 2020-2021 Reopening Plan

Finn Academy 2020 - 2021 Re opening Plan The Path Forward. 1 Table of Contents 1| Table of Contents…………………………………………………………………….2 2| Introduction – Letter from the Board of Trustees………………….3 3| Plan Development…………………………………………………………………..4 Executive Summary Guiding Principles Committee Work 4| The Plan……………………………………………………………………………………6 Reopening Operations, Monitoring, Containment and Closure………………………………………………………………………………….6 Pre-Opening, School Calendars & Scheduling…………………39 Enrollment and Attendance………………………..……………………..54 Academic Program…………………………………………………………….56 2 Letter from the Board of Trustees Dear Finn Families, It seems an eternity since February 11th when we celebrated receiving a three-year extension on our charter. Who could imagine the heartbreak that one month later, we would be forced to shut down for the remainder of the school year? While we are certainly living through unprecedented times, our Board recognizes the challenges that you and your children faced in light of the circumstances surrounding the pandemic, and you have all demonstrated the character that makes Finn Academy unique. We are pleased with and inspired by our teachers and staff who worked tirelessly to ensure that your scholars remained connected to their school during that uncertainty. We are proud of your scholars for persevering and doing their very best, despite the frustrating moments they faced. And we are deeply appreciative that as parents, grandparents, and care givers, you allowed us the honor of having your children remain with us. As a school community, it is important that we pause and appreciate all that we have accomplished in light of these challenges. Our core principles of scholarship, perseverance, aspiration, reflection, kindness, and leadership are the tools that will help us continue to successfully navigate the unknown that lies ahead of us. -

Mason 2015 02Thesis.Pdf (1.969Mb)

‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Author Mason, Paul James Published 2015 Thesis Type Thesis (Professional Doctorate) School Queensland College of Art DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3741 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367413 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au ‘Page 1, Panel 1…” Creating an Australian Comic Book Series Paul James Mason s2585694 Bachelor of Arts/Fine Art Major Bachelor of Animation with First Class Honours Queensland College of Art Arts, Education and Law Group Griffith University Submitted in fulfillment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Visual Arts (DVA) June 2014 Abstract: What methods do writers and illustrators use to visually approach the comic book page in an American Superhero form that can be adapted to create a professional and engaging Australian hero comic? The purpose of this research is to adapt the approaches used by prominent and influential writers and artists in the American superhero/action comic-book field to create an engaging Australian hero comic book. Further, the aim of this thesis is to bridge the gap between the lack of academic writing on the professional practice of the Australian comic industry. In order to achieve this, I explored and learned the methods these prominent and professional US writers and artists use. Compared to the American industry, the creating of comic books in Australia has rarely been documented, particularly in a formal capacity or from a contemporary perspective. The process I used was to navigate through the research and studio practice from the perspective of a solo artist with an interest to learn, and to develop into an artist with a firmer understanding of not only the medium being engaged, but the context in which the medium is being created. -

BATMAN Basic and Advanced Tractography with Mrtrix for All Neurophiles

Beyond the tensor model BATMAN Basic and Advanced Tractography with MRtrix for All Neurophiles Marlene Tahedl Biomedical Imaging Group University of Regensburg BATMAN: General tutorial info Marlene Tahedl 1 General tutorial info .............................................................................................................. 3 1.1 About the tutorial ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 About the tutorial data .............................................................................................................. 4 1.2.1 Tutorial data structure .......................................................................................................... 4 1.2.2 Data acquisition .................................................................................................................... 4 1.2.3 Subject information and data sharing policy ......................................................................... 5 1.3 Software requirements/more useful hints ................................................................................ 5 2 Getting started: Preprocessing ............................................................................................. 6 2.1 Preparatory steps ...................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Denoising .................................................................................................................................. -

A Triage Approach to Streamline Environmental Footprinting: a Case Study for Liquid Crystal Displays

A Triage Approach to Streamline Environmental Footprinting: A Case Study for Liquid Crystal Displays by Melissa Lee Zgola B.S. Environmental Engineering Technology Cornell University, 2005 Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of ARCHIVES Master of Science in Technology and Policy IFMAssACHussr- s at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology NOV 0 September 2011 L A R F C 2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. Signature of author s"Tebhno~ did Policy Program July 14, 2011 1 ,4// // / Certified by Randolp1 E. Kirchain Principle Research Associate, Engineering Systems Division Thesis Supervisor Accepted by rroi ssor ujava J. Newman Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics an Engineering Systems Director of Technology and Policy Program (this page intentionally left blank) 2 A Triage Approach to Streamline Environmental Footprinting: A Case Study for Liquid Crystal Displays by Melissa Lee Zgola Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division on July 14, 2011 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Technology and Policy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology ABSTRACT Quantitative environmental performance evaluation methods are desired given the growing certification and labeling landscape for consumer goods. Challenges associated with existing methods, such as life cycle assessment (LCA), may be prohibitive for complex goods such as information technology (IT). Conventional LCA is resource-intensive and lacks harmonized guidance for incorporating uncertainty. Current methods to streamline LCA may amplify uncertainty, undermining robustness. Despite high uncertainty, effective and efficient streamlining approaches may be possible. A methodology is proposed to identify high-impact activities within the life cycle of a specific product class for a streamlined assessment with a high degree of inherent uncertainty. -

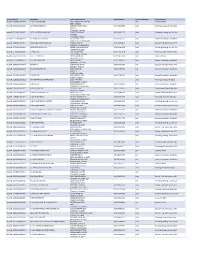

Contractor List

Active Licenses DBA Name Full Primary Address Work Phone # Licensee Category SIC Description buslicBL‐3205002/ 28/2020 1 ON 1 TECHNOLOGY 417 S ASSOCIATED RD #185 cntr Electrical Work BREA CA 92821 buslicBL‐1684702/ 28/2020 1ST CHOICE ROOFING 1645 SEPULVEDA BLVD (310) 251‐8662 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met UNIT 11 TORRANCE CA 90501 buslicBL‐3214602/ 28/2021 1ST CLASS MECHANICAL INC 5505 STEVENS WAY (619) 560‐1773 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con #741996 SAN DIEGO CA 92114 buslicBL‐1617902/ 28/2021 2‐H CONSTRUCTION, INC 2651 WALNUT AVE (562) 424‐5567 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia SIGNAL HILL CA 90755‐1830 buslicBL‐3086102/ 28/2021 200 PSI FIRE PROTECTION CO 15901 S MAIN ST (213) 763‐0612 subc Special Trade Contractors, NEC GARDENA CA 90248‐2550 buslicBL‐0778402/ 28/2021 20TH CENTURY AIR, INC. 6695 E CANYON HILLS RD (714) 514‐9426 subc Plumbing, Heating, and Air‐Con ANAHEIM CA 92807 buslicBL‐2778302/ 28/2020 3 A ROOFING 762 HUDSON AVE (714) 785‐7378 subc Roofing, Siding, and Sheet Met COSTA MESA CA 92626 buslicBL‐2864402/ 28/2018 3 N 1 ELECTRIC INC 2051 S BAKER AVE (909) 287‐9468 cntr Electrical Work ONTARIO CA 91761 buslicBL‐3137402/ 28/2021 365 CONSTRUCTION 84 MERIDIAN ST (626) 599‐2002 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia IRWINDALE CA 91010 buslicBL‐3096502/ 28/2019 3M POOLS 1094 DOUGLASS DR (909) 630‐4300 cntr Special Trade Contractors, NEC POMONA CA 91768 buslicBL‐3104202/ 28/2019 5M CONTRACTING INC 2691 DOW AVE (714) 730‐6760 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia UNIT C‐2 TUSTIN CA 92780 buslicBL‐2201302/ 28/2020 7 STAR TECH 2047 LOMITA BLVD (310) 528‐8191 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia LOMITA CA 90717 buslicBL‐3156502/ 28/2019 777 PAINTING & CONSTRUCTION 1027 4TH AVE subc Painting and Paper Hanging LOS ANGELES CA 90019 buslicBL‐1920202/ 28/2020 A & A DOOR 10519 MEADOW RD (213) 703‐8240 cntr General Contractors‐Residentia NORWALK CA 90650‐8010 buslicBL‐2285002/ 28/2021 A & A HENINS, INC. -

MCN Streamline Fall 2016

streThe Maigrant Hemalth News SourcelinVolume 22, e Issue 3 • Fall 2016 Crisis in the Countryside: Addressing the Opioid Epidemic in Rural Washington and Idaho By Claire Hutkins Seda, Writer, Migrant Clinicians Network, Managing Editor, Streamline he opioid crisis touches all sectors of of MCN’s External Advisory Board. He points capacity.’” Many health clinics around the America’s patient population — espe - out that patients with chronic pain are the country can relate. Once high opioid use Tcially underserved patients like agricul - population that is at high risk for chronic patients are identified, next comes the ardu - tural workers in rural areas. In Washington high opioid use. The goal of the project is to ous and seemingly unprecedented work of and Idaho, six rural health clinics represent - improve safe prescribing of chronic opioid figuring out how to best adjust policy, pro - ing over 20 sites are working through the medication for patients with non-cancer pain cedure, and workflow to serve those patients difficult questions to make sure their policies, at these rural clinics, which are affiliated with and address the crisis head-on. workflow, and clinical visits are all aligned critical access hospitals. But the task is not The project approaches the problem in and implemented to address the crisis that easy, both because the tools are lacking, and part through guided self-assessments and has swept the nation. because the problem is so big. 2shared learning opportunities, during “A lot of the people who live in [these] “Ideally, patients with chronic pain on which the clinics can dive into the project’s rural areas have agricultural and other types opioid medication should be seen every 90 six building blocks for safe, team-based opi - of jobs that are very physically demanding. -

![Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7100/incorporating-flow-for-a-comic-book-corrective-of-rhetcon-2937100.webp)

Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon

INCORPORATING FLOW FOR A COMIC [BOOK] CORRECTIVE OF RHETCON Garret Castleberry Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Brian Lain, Major Professor Shaun Treat, Co-Major Professor Karen Anderson, Committee Member Justin Trudeau, Committee Member John M. Allison Jr., Chair, Department of Communication Studies Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Castleberry, Garret. Incorporating Flow for a Comic [Book] Corrective of Rhetcon. Master of Arts (Communication Studies), May 2010, 137 pp., references, 128 titles. In this essay, I examined the significance of graphic novels as polyvalent texts that hold the potential for creating an aesthetic sense of flow for readers and consumers. In building a justification for the rhetorical examination of comic book culture, I looked at Kenneth Burke’s critique of art under capitalism in order to explore the dimensions between comic book creation, distribution, consumption, and reaction from fandom. I also examined Victor Turner’s theoretical scope of flow, as an aesthetic related to ritual, communitas, and the liminoid. I analyzed the graphic novels Green Lantern: Rebirth and Y: The Last Man as case studies toward the rhetorical significance of retroactive continuity and the somatic potential of comic books to serve as equipment for living. These conclusions lay groundwork for multiple directions of future research. Copyright 2010 by Garret Castleberry ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are several faculty and family deserving recognition for their contribution toward this project. First, at the University of North Texas, I would like to credit my co-advisors Dr. Brian Lain and Dr. -

Batman and the Superhero Fairytale: Deconstructing a Revisionist Crisis

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2013 Batman and the superhero fairytale: deconstructing a revisionist crisis Travis John Landhuis University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2013 Travis John Landhuis Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Landhuis, Travis John, "Batman and the superhero fairytale: deconstructing a revisionist crisis" (2013). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 34. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/34 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by TRAVIS JOHN LANDHUIS 2013 All Rights Reserved BATMAN AND THE SUPERHERO FAIRYTALE: DECONSTRUCTING A REVISIONIST CRISIS An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Travis John Landhuis University of Northern Iowa December 2013 ABSTRACT Contemporary superhero comics carry the burden of navigating historical iterations and reiterations of canonical figures—Batman, Superman, Green Lantern et al.—producing a tension unique to a genre that thrives on the reconstruction of previously established narratives. This tension results in the complication of authorial and interpretive negotiation of basic principles of narrative and structure as readers and producers must seek to construct satisfactory identities for these icons. Similarly, the post-modern experimentation of Robert Coover—in Briar Rose and Stepmother—argues that we must no longer view contemporary fairytales as separate (cohesive) entities that may exist apart from their source narratives.