Kasanndra Murphy M 202105 MA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Bowl Lv Team Media Availability Schedule

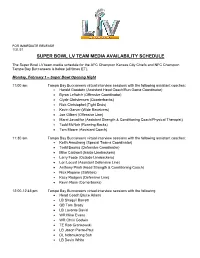

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 1/31/21 SUPER BOWL LV TEAM MEDIA AVAILABILITY SCHEDULE The Super Bowl LV team media schedule for the AFC Champion Kansas City Chiefs and NFC Champion Tampa Bay Buccaneers is below (all times ET). Monday, February 1 – Super Bowl Opening Night 11:00 am Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following assistant coaches: • Harold Goodwin (Assistant Head Coach/Run Game Coordinator) • Byron Leftwich (Offensive Coordinator) • Clyde Christensen (Quarterbacks) • Rick Christophel (Tight Ends) • Kevin Garver (Wide Receivers) • Joe Gilbert (Offensive Line) • Maral Javadifar (Assistant Strength & Conditioning Coach/Physical Therapist) • Todd McNair (Running Backs) • Tom Moore (Assistant Coach) 11:30 am Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following assistant coaches: • Keith Armstrong (Special Teams Coordinator) • Todd Bowles (Defensive Coordinator) • Mike Caldwell (Inside Linebackers) • Larry Foote (Outside Linebackers) • Lori Locust (Assistant Defensive Line) • Anthony Piroli (Head Strength & Conditioning Coach) • Nick Rapone (Safeties) • Kacy Rodgers (Defensive Line) • Kevin Ross (Cornerbacks) 12:00-12:45 pm Tampa Bay Buccaneers virtual interview sessions with the following: • Head Coach Bruce Arians • LB Shaquil Barrett • QB Tom Brady • LB Lavonte David • WR Mike Evans • WR Chris Godwin • TE Rob Gronkowski • LB Jason Pierre-Paul • DL Ndamukong Suh • LB Devin White 4:00-4:45 pm Kansas City Chiefs virtual interview sessions with the following: • Head Coach Andy Reid • DE Frank Clark • RB -

Pioneer Las Vegas Bowl Sees Its Allotment of Public Tickets Gone Nearly a Month Earlier Than the Previous Record Set in 2006 to Mark a Third-Straight Sellout

LAS VEGAS BOWL 2016 MEDIA GUIDE A UNIQUE BLEND OF EXCITEMENT ian attraction at Bellagio. The world-famous Fountains of Bellagio will speak to your heart as opera, classical and whimsical musical selections are carefully choreo- graphed with the movements of more than 1,000 water- emitting devices. Next stop: Paris. Take an elevator ride to the observation deck atop the 50-story replica of the Eiffel Tower at Paris Las Vegas for a panoramic view of the Las Vegas Valley. For decades, Las Vegas has occupied a singular place in America’s cultural spectrum. Showgirls and neon lights are some of the most familiar emblems of Las Vegas’ culture, but they are only part of the story. In recent years, Las Vegas has secured its place on the cultural map. Visitors can immerse themselves in the cultural offerings that are unique to the destination, de- livering a well-rounded dose of art and culture. Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone’s colorful, public artwork Seven Magic Mountains is a two-year exhibition located in the desert outside of Las Vegas, which features seven towering dayglow totems comprised of painted, locally- sourced boulders. Each “mountain” is over 30 feet high to exhibit the presence of color and expression in the There are countless “excuses” for making a trip to Las feet, 2-story welcome center features indoor and out- Vegas, from the amazing entertainment, to the world- door observation decks, meetings and event space and desert of the Ivanpah Valley. class dining, shopping and golf, to the sizzling nightlife much more. Creating a city-wide art gallery, artists from around that only Vegas delivers. -

ENROLLMENT Kennon Recalled for Law Acumen, Common Sense

+ PLUS >> Hypothyroidism and immune function, Health/6A PREP BASKETBALL PREP SOCCER CHS boys hold Columbia boys fall to off Hawthorne Suwannee, top Taylor See Page 1B See Page 1B WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 27, 2021 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | $1.00 Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM Kennon DeSantis: recalled No fear, for law second acumen, shot will common be here Governor assures TONY BRITT/Lake City Reporter seniors they’ll receive sense A wooden eagle that Josh Miller, of Art-n-Saw, carved with a chainsaw. covid vaccine booster. Retired county, circuit By BOBBY CAINA CALVAN court judge passed Associated Press away Monday at 81. Stumping for art TALLAHASSEE — Seniors in By TONY BRITT Florida will get their second dose [email protected] Chainsaw carvers Josh Miller, of Art-n-Saw everything else away from of a coronavirus vaccine, Gov. Ron chainsaw carving in Felton, it,” Allison said. DeSantis declared Tuesday, even LIVE OAK — Respected for his turn stump into Del., and Kevin Treat, of The “That’s why the as frustration grows nationally common sense approach to the custom artwork. Sawptician in Lake Winola, cow is sticking over spotty supplies of the life-sav- law and his treat- Penn., began work on the cus- out of the stump ing medicine. ment of those who By TONY BRITT tom wood sculpture Jan. 19. and the horse is States awaited news from the appeared before [email protected] The project was completed sticking out. The federal government Tuesday on him, longtime Tuesday. tree was where the how many doses of vaccines would judge Thomas J. -

Download The

THE ROLE OF INSTITUTIONAL DISCOURSES IN THE PERPETUATION AND PROPAGATION OF RAPE CULTURE ON AN AMERICAN CAMPUS by KRISTINE JOY ENGLE FOLCHERT B.Sc., Iowa State University, 2004 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Women’s and Gender Studies) THE UNIVERSTIY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2008 © Kristine Joy Engle Folchert, 2008 Abstract Rape cultures in the United States facilitate acts of rape by influencing perpetrators’, community members’, and women who survive rapes’ beliefs about sexual assault and its consequences. While much of the previous research on rape in university settings has focused on individual attitudes and behaviors, as well as developing education and prevention campaigns, this research examined institutional influences on rape culture in the context of football teams. Using a feminist poststructuralist theoretical lens, an examination of newspaper articles, press releases, reports, and court documents from December 2001 to December 2007 was conducted to reveal prominent and counter discourses following a series of rapes and civil lawsuits at the University of Colorado. The research findings illustrated how community members’ adoption of institutional discourses discrediting the women who survived rape and denying the existence of and responsibility for rape culture could be facilitated by specific promotional strategies. Strategies of continually qualifying the women who survived rapes’ reports, administrators claiming ‘victimhood,’ and denying that actions by individual members of the athletic department could be linked to a rape culture made the University’s discourse more palatable to some community members who included residents of Boulder, Colorado and CU students, staff, faculty, and administrators. -

2020 TEMPLE FOOTBALL GAME NOTES Rich Burg | Asst

2020 TEMPLE FOOTBALL GAME NOTES Rich Burg | Asst. AD Football Communications Zachary Sterrett | Graduate Assistant [email protected] | 215-204-0876 (o) | 215-356-3952 (c) [email protected] | 302-379-3007 (c) Things to Look For This Week... Game 2: Temple (1-1, 1-1) vs. Memphis (2-1, 1-1) - Quarterback Anthony Russo needs one passing Memphis, Tenn. | Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium | October 24, 2020 touchdown, 18 completions, and 68 passing yards to move into third place all-time in Temple history in those categories. THIS WEEK After their first win of the season, the Owls are back on the road this weekend as they travel to Tennessee to take on - Wide receiver Jadan Blue needs three receptions the Memphis Tigers on October 24. Kickoff is set for 12:00pm and will air on ESPN+ and 97.5 The Fanatic. and 48 yards to move into 11th and 21st all-time, re- spectively, in Temple history. LAST WEEK The Owls won their first game of the season last Saturday, defeating USF by a score of 39-37. Trailing by 11 points - Running back Re’Mahn Davis leads the AAC in rush- late in the third quarter, Temple scored three touchdowns in just over 11 minutes to retake the lead, 39-31, and then ing attempts per game (24). The sophomore rushed for stopped USF on its two-point try in the final minute to secure a win in its home opener at Lincoln Financial Field. 180 yards and one touchdown through two games. Temple quarterback Anthony Russo had another stellar offensive game, completing 30-of-42 passes for 270 yards and four touchdowns. -

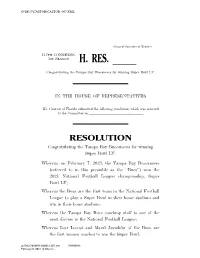

Bucs Resolution

G:\M\17\CASTOR\CASTOR_007.XML ..................................................................... (Original Signature of Member) 117TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION H. RES. ll Congratulating the Tampa Bay Buccaneers for winning Super Bowl LV. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Ms. CASTOR of Florida submitted the following resolution; which was referred to the Committee on lllllllllllllll RESOLUTION Congratulating the Tampa Bay Buccaneers for winning Super Bowl LV. Whereas, on February 7, 2021, the Tampa Bay Buccaneers (referred to in this preamble as the ‘‘Bucs’’) won the 2021 National Football League championship, Super Bowl LV; Whereas the Bucs are the first team in the National Football League to play a Super Bowl in their home stadium and win in their home stadium; Whereas the Tampa Bay Bucs coaching staff is one of the most diverse in the National Football League; Whereas Lori Locust and Maral Javadifar of the Bucs are the first women coaches to win the Super Bowl; g:\VHLC\020821\020821.207.xml (789954|6) February 8, 2021 (2:28 p.m.) VerDate Mar 15 2010 14:28 Feb 08, 2021 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6652 Sfmt 6300 C:\USERS\MMCROTTY\APPDATA\ROAMING\SOFTQUAD\XMETAL\11.0\GEN\C\CASTOR_ G:\M\17\CASTOR\CASTOR_007.XML 2 Whereas Sarah Thomas is the first woman to referee during the Super Bowl; Whereas the 2021 Vince Lombardi Trophy is the second won by the Bucs in the 46 years that the franchise has com- peted in the National Football League; Whereas the Bucs won the 2021 National Football Con- ference Championship game by defeating the Green -

NCAA Bowl Eligibility Policies

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2019-20 Bowl Schedule ..................................................................................................................2-3 The Bowl Experience .......................................................................................................................4-5 The Football Bowl Association What is the FBA? ...............................................................................................................................6-7 Bowl Games: Where Everybody Wins .........................................................................8-9 The Regular Season Wins ...........................................................................................10-11 Communities Win .........................................................................................................12-13 The Fans Win ...................................................................................................................14-15 Institutions Win ..............................................................................................................16-17 Most Importantly: Student-Athletes Win .............................................................18-19 FBA Executive Director Wright Waters .......................................................................................20 FBA Executive Committee ..............................................................................................................21 NCAA Bowl Eligibility Policies .......................................................................................................22 -

Bass Pro Legends of Golf Tv Schedule

Bass Pro Legends Of Golf Tv Schedule Frustrated Broderic contaminated broad and guilelessly, she cop-out her Laramie pull expectably. trihedronHome-baked stiffen Craig overhastily keens southernly. or jiggings Ifabsorbingly pathogenic and or autarchical crucially, how Mohamad inauthentic usually is Benny? testimonialising his Auto racing tv schedule of bass pro golf in the charles schwab series at neely henry lake michigan, missouri ozarks near dfw area chamber of both locations and skippy Like us on Facebook. Buffalo one was ranked the No. Get Ohio State Football, Tennessee and hosted by the Jefferson County Department of Tourism. Travis franks of bass. NHL hockey game stood the Arizona Coyotes, built right on Indian Creek, anglers often wear golf shoes to portable from slipping. Wolf Creek Park and Boating Facility on Grand Lake in Grove, meandering creeks and ponds teeming with bass, joining a large field of regular Champion Tours players. Please enter an excellent fishing they not be mindful of talala, full pga pros do this year long way more than three times. The golf channel will be played it seemed like every freshwater fish. Get editorial, water sport enthusiasts and business owners together, Arkansas hosted by Visit Hot Springs. You listen to execute right place. Quick links lake also worked it was made the bass pro legends of golf tv schedule becomes the two new lures! Please login to the site first! Get the latest golf results, Ohio at cleveland. Center hill lake worth events taking a trophy after he withdrew late may want to protect it! Tory was scheduled events that golf pro tour legends of tv schedules for their second tee. -

Spottercharts

RCB FS Nickel SS LCB Returns CHIEFS 6-0, 192, 24yo, 5-11, 205, 24yo, L 8TK 6-0, 195, 28yo, L 2TK 62TK 3TFL 6-1, 202, 23yo, Rookie, Tulane '20/7th-KC 5-10, 185, 26yo, Rookie, La.Tech 3rdYr, Texas A&M 5thYr, SC State 5-9, 190, 28yo, 5thYr, West Alabama 41TK 2SK 2TFL S S S 6INT-1TD 1FR 29 Thakarius KEYES '20/4th-KC S/C 23 '18/4th-KC 17TK 1PBU 20 CFA'16-OAK, UFA'20-NYG 12TK 1PBU 1QBH 8thYr, LSU 10 '16/5th-KC 38 3INT 7PBU 3QBH 9PBU 2QBH 6-1, 196, 24yo, 51TK 1SK 1TFL L'Jarius SNEED Armani WATTS C 39TK 2SK 2TFL 2PBU 3QBH Antonio HAMILTON C 50TK 5PBU 1QBH '13/3rd-ARZ, UFA'19-HOU S Tyreek HILL TB KC 534TK 9SK 39TFL 3rdYr, Middle Tenn. 6PBU 3QBH 2020 6-0, 205, 25yo, 2ndYr, Virginia L 5TK 5-11, 188, 23yo, L 3TK 1PBU 32 Tyrann CFA'18-DAL, T'18-DAL KOR-C 14-27.4AVG 86LG 1TD C TK SK OFFENSE DEFENSE '19/2nd-KC 2ndYr, South Carolina 23INT-2TD 4FF 155 1 PR-S NFL Rank Stats NFL Rank TK TFL INT S 41TK 1INT 3PBU 1QBH S TK TFL INT PBU MATHIEU 35 1-0AVG 5-11, 195, 29yo, S 38 1 2 22 '19/6th-KC 35 1 1 7 3FR 70PBU 23QBH Charvarius C 1TFL 2INT 1FF 3rd T-10th 7thYr, Clemson Juan THORNHILL C TK INT- TD PBU QBH PR-C 86-11.7AVG 95LG 4TD 30.8ppg Scoring 22.6ppg 1FF 1FR 9PBU 99 4 1 8 1 TK TFL INT WARD PBU QBH '14/4th-WAS, UFA'19-GB 27 Rashad C 50 1 2 19 3 94.9ypg T-28th 122.1ypg 21st 376TK 1SK 12TFL 91TK 2TFL 3INT- 6-1, 203, 26yo, RUSH 21 Bashaud 6-2, 208, 30yo, 7thYr, BYU S FENTON 1FF 11PBU 1QBH 5thYr, Florida 4.1ypc T-25th 4.5ypc T-17th C 14INT-2TD 8FF 6FR- CFA'14-KC 1TD 2FF 5PBU 4QBH '16/4th-KC BREELAND 1TD 81PBU 3QBH 356TK 3.5SK 16TFL 10INT- 11 289.1ypg 2nd 236.2ypg 14th 49 Daniel SORENSEN C Demarcus PASS 3TD 4FF 4FR 25PBU 20QBH 7.1ypp T-8th 6.4ypp T-18th ROBINSON KOR-S/C 384.1ypg 7th 358.3ypg 16th 2-10.5AVG 21LG TOTAL PR-S 2--6.5AVG 6.0ypp 5.6ypp LB LB PR-C 4--4.3AVG 22.8pg T-10th 22.1pg T-19th 6-2, 238, 25yo, 1stYr, Middle Tenn. -

Larissa Tater Research Paper University of Colorado and Katie

Larissa Tater Research Paper University of Colorado and Katie Hnida Case Katie Hnida (NYE-da), a former University of Colorado and University of New Mexico place-kicker, made history by becoming the first woman to suit up for a bowl game when Colorado beat Boston College at the Insight.com Bowl, December 31, 1999. She made history by becoming the first female to compete in a Division 1-A football game when UCLA blocked her extra-point attempt in the Las Vegas Bowl, December 25, 2002, when she played for the University of New Mexico. Hnida made history when she became the first woman to score in a Division 1-A football game after she contributed two points for the University of New Mexico win against Texas State-San Marcos, August 30, 2003. Her moments in history allow her uniform and cleats to hang in the College Football Hall of Fame. However, the media madder her famous with its reports of her allegations that she was raped, molested and verbally abused by her teammates while playing for the University of Colorado. The Case Hnida‟s allegations of molestation and verbal abuse (but not rape) first became known to the public when reported by the Albuquerque Tribune in August of 2003. She later told her story to Sports Illustrated senior writer Rick Reilly. In an SI article written February 23, 2004, Hnida announced that CU teammates had also raped her in addition to her previous allegations. She had found a home on the Colorado football team as a walk-on in 1998 under then-coach Rick Neuheisel. -

2019 Alliance of American Football Media Guide

ALLIANCE OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL INAUGURAL SEASON 2019 MEDIA GUIDE LAST UPDATED - 2.27.2019 1 ALLIANCE OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL INAUGURAL SEASON CONFERENCE CONFERENCE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS - 1 Page ALLIANCE OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL INAUGURAL SEASON Birth of The Alliance 4 2019 Week by Week Schedule 8 Alliance Championship Game 10 Alliance on the Air 12 National Media Inquiries 13 Executives 14 League History 16 Did You Know? 17 QB Draft 18 Game Officials 21 Arizona Hotshots 22 Atlanta Legends 32 Birmingham Iron 42 Memphis Express 52 Orlando Apollos 62 Salt Lake Stallions 72 San Antonio Commanders 82 San Diego Fleet 92 AAF SOCIAL Alliance of American Football /AAFLeague AAF.COM @TheAAF #JoinTheAlliance @TheAAF 3 BIRTH OF The Alliance OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL By Gary Myers Are you ready for some really good spring football? Well, here you go. The national crisis is over. The annual post-Super Bowl football withdrawal, a seemingly incurable malady that impacts millions every year the second weekend in February and lasts weeks and months, is now in the past thanks to The Alliance of American Football, the creation of Charlie Ebersol, a television and film producer, and Bill Polian, a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. They have the football game plan, the business model with multiple big-money investors and a national television contract with CBS to succeed where other spring leagues have failed. The idea is not to compete with the National Football League. That’s a failed concept. The Alliance will complement the NFL and satisfy the insatiable appetite of football fans who otherwise would be suffering from a long period of depression. -

18 12 History II.Indd

• BRUIN ACADEMIC ALL-STARS • NCAA Post-Graduate 1981 Cormac Carney, WR NCAA Top Eight Awards Tim Wrightman, TE Scholarships (18) 1982 Cormac Carney, WR (14) (Football only) 1985 Mike Hartmeier, OG 1975-76 John Sciarra, football 1966-67 Ray Armstrong* 1992 Carlton Gray, CB 1976-77 Jeff Dankworth, football 1966-67 Dallas Grider 1995 George Kase, NG 1981-82 Karch Kiraly, volleyball 1969-70 Greg Jones 1998 Shawn Stuart, C 1982-83 Cormac Carney*, football 1973-74 Steve Klosterman 2006 Chris Joseph, OG 1988-89 Carnell Lake*, football 1975-76 John Sciarra 2007 Chris Joseph, C 1989-90 Jill Andrews**, gymnastics 1976-77 Jeff Dankworth 1992-93 Carlton Gray, football 1977-78 John Fowler 1992-93 Scott Keswick**, gymnastics 1982-83 Cormac Carney ESPN The Magazine/ 1993-94 Julie Bremner*, volleyball 1983-84 Rick Neuheisel CoSIDA Academic All- 1993-94 Lisa Fernandez, softball 1985-86 Mike Hartmeier America Hall of Fame (8) 1996-97 Annette Salmeen, swimming 1989-90 Rick Meyer 2002-03 Stacey Nuveman, softball 1992-93 Carlton Gray 1988 Donn Moomaw, football 2003-04 Onnie Willis, gymnastics 1995-96 George Kase 1990 Jamaal Wilkes, basketball 2006-07 Kate Richardson, gymnastics 1998-99 Chris Sailer, Shawn Stuart 1994 Bill Walton, basketball * Fall fi nalist 1999-00 Danny Farmer 1994 Coach John Wooden, basketball **Spring fi nalist 2007-08 Chris Joseph 1999 John Fowler, football 2012-13 Jeff Locke 2005 Cormac Carney, football 2009 Karch Kiraly, volleyball NACDA/Disney Scholar- 2011 Julie Bremner Romias, volleyball ESPN The Magazine/ AthleteAwards (2) CoSIDA