The Magic Hour: Film at Fin De Siècle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

GLAAD Media Institute Began to Track LGBTQ Characters Who Have a Disability

Studio Responsibility IndexDeadline 2021 STUDIO RESPONSIBILITY INDEX 2021 From the desk of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis In 2013, GLAAD created the Studio Responsibility Index theatrical release windows and studios are testing different (SRI) to track lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and release models and patterns. queer (LGBTQ) inclusion in major studio films and to drive We know for sure the immense power of the theatrical acceptance and meaningful LGBTQ inclusion. To date, experience. Data proves that audiences crave the return we’ve seen and felt the great impact our TV research has to theaters for that communal experience after more than had and its continued impact, driving creators and industry a year of isolation. Nielsen reports that 63 percent of executives to do more and better. After several years of Americans say they are “very or somewhat” eager to go issuing this study, progress presented itself with the release to a movie theater as soon as possible within three months of outstanding movies like Love, Simon, Blockers, and of COVID restrictions being lifted. May polling from movie Rocketman hitting big screens in recent years, and we remain ticket company Fandango found that 96% of 4,000 users hopeful with the announcements of upcoming queer-inclusive surveyed plan to see “multiple movies” in theaters this movies originally set for theatrical distribution in 2020 and summer with 87% listing “going to the movies” as the top beyond. But no one could have predicted the impact of the slot in their summer plans. And, an April poll from Morning COVID-19 global pandemic, and the ways it would uniquely Consult/The Hollywood Reporter found that over 50 percent disrupt and halt the theatrical distribution business these past of respondents would likely purchase a film ticket within a sixteen months. -

DVD Movie List by Genre – Dec 2020

Action # Movie Name Year Director Stars Category mins 560 2012 2009 Roland Emmerich John Cusack, Thandie Newton, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 158 min 356 10'000 BC 2008 Roland Emmerich Steven Strait, Camilla Bella, Cliff Curtis Action 109 min 408 12 Rounds 2009 Renny Harlin John Cena, Ashley Scott, Aidan Gillen Action 108 min 766 13 hours 2016 Michael Bay John Krasinski, Pablo Schreiber, James Badge Dale Action 144 min 231 A Knight's Tale 2001 Brian Helgeland Heath Ledger, Mark Addy, Rufus Sewell Action 132 min 272 Agent Cody Banks 2003 Harald Zwart Frankie Muniz, Hilary Duff, Andrew Francis Action 102 min 761 American Gangster 2007 Ridley Scott Denzel Washington, Russell Crowe, Chiwetel Ejiofor Action 113 min 817 American Sniper 2014 Clint Eastwood Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Kyle Gallner Action 133 min 409 Armageddon 1998 Michael Bay Bruce Willis, Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck Action 151 min 517 Avengers - Infinity War 2018 Anthony & Joe RussoRobert Downey Jr., Chris Hemsworth, Mark Ruffalo Action 149 min 865 Avengers- Endgame 2019 Tony & Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr, Chris Evans, Mark Ruffalo Action 181 mins 592 Bait 2000 Antoine Fuqua Jamie Foxx, David Morse, Robert Pastorelli Action 119 min 478 Battle of Britain 1969 Guy Hamilton Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Harry Andrews Action 132 min 551 Beowulf 2007 Robert Zemeckis Ray Winstone, Crispin Glover, Angelina Jolie Action 115 min 747 Best of the Best 1989 Robert Radler Eric Roberts, James Earl Jones, Sally Kirkland Action 97 min 518 Black Panther 2018 Ryan Coogler Chadwick Boseman, Michael B. Jordan, Lupita Nyong'o Action 134 min 526 Blade 1998 Stephen Norrington Wesley Snipes, Stephen Dorff, Kris Kristofferson Action 120 min 531 Blade 2 2002 Guillermo del Toro Wesley Snipes, Kris Kristofferson, Ron Perlman Action 117 min 527 Blade Trinity 2004 David S. -

Robert De Niro's Raging Bull

003.TAIT_20.1_TAIT 11-05-12 9:17 AM Page 20 R. COLIN TAIT ROBERT DE NIRO’S RAGING BULL: THE HISTORY OF A PERFORMANCE AND A PERFORMANCE OF HISTORY Résumé: Cet article fait une utilisation des archives de Robert De Niro, récemment acquises par le Harry Ransom Center, pour fournir une analyse théorique et histo- rique de la contribution singulière de l’acteur au film Raging Bull (Martin Scorcese, 1980). En utilisant les notes considérables de De Niro, cet article désire montrer que le travail de cheminement du comédien s’est étendu de la pré à la postproduction, ce qui est particulièrement bien démontré par la contribution significative mais non mentionnée au générique, de l’acteur au scénario. La performance de De Niro brouille les frontières des classes de l’auteur, de la « star » et du travail de collabo- ration et permet de faire un portrait plus nuancé du travail de réalisation d’un film. Cet article dresse le catalogue du processus, durant près de six ans, entrepris par le comédien pour jouer le rôle du boxeur Jacke LaMotta : De la phase d’écriture du scénario à sa victoire aux Oscars, en passant par l’entrainement d’un an à la boxe et par la prise de soixante livres. Enfin, en se fondant sur des données concrètes qui sont restées jusqu’à maintenant inaccessibles, en raison de la modestie et du désir du comédien de conserver sa vie privée, cet article apporte une nouvelle perspective pour considérer la contribution importante de De Niro à l’histoire américaine du jeu d’acteur. -

7 1Stephen A

SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Bachelor of Fine Arts in Film Production New York University 1985 Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture & Planning in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September, 1990 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1990 All Rights Reserved I Signature of Author Media Arts & Sciences Section Certified by '4 A Professor Glorianna Davenport Assistant Professor of Media Technology, MIT Media Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by I~ I ~ - -- 7 1Stephen A. Benton Chairperso,'h t fCommittee on Graduate Students OCT 0 4 1990 LIBRARIES iznteh Room 14-0551 77 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02139 Ph: 617.253.2800 MITLibraries Email: [email protected] Document Services http://libraries.mit.edu/docs DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as soon as possible. Thank you. Best copy available. SLIPSTREAM A DATA RICH PRODUCTION ENVIRONMENT by Alan Lasky Submitted to the Media Arts & Sciences Section, School of Architecture and Planning on August 10, 1990 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science ABSTRACT Film Production has always been a complex and costly endeavour. Since the early days of cinema, methodologies for planning and tracking production information have been constantly evolving, yet no single system exists that integrates the many forms of production data. -

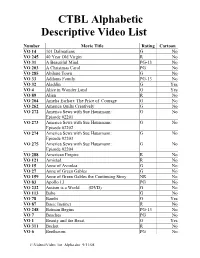

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List

CTBL Alphabetic Descriptive Video List Number Movie Title Rating Cartoon VO 14 101 Dalmatians G No VO 245 40 Year Old Virgin R No VO 31 A Beautiful Mind PG-13 No VO 203 A Christmas Carol PG No VO 285 Abilene Town G No VO 33 Addams Family PG-13 No VO 32 Aladdin G Yes VO 4 Alice in Wonder Land G Yes VO 89 Alien R No VO 204 Amelia Earhart: The Price of Courage G No VO 262 America Quilts Creatively G No VO 272 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2201 VO 273 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2202 VO 274 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2203 VO 275 America Sews with Sue Hausmann: G No Episode #2204 VO 288 American Empire R No VO 121 Amistad R No VO 15 Anne of Avonlea G No VO 27 Anne of Green Gables G No VO 159 Anne of Green Gables the Continuing Story NR No VO 83 Apollo 13 PG No VO 232 Autism is a World (DVD) G No VO 113 Babe G No VO 78 Bambi G Yes VO 87 Basic Instinct R No VO 248 Batman Begins PG-13 No VO 7 Beaches PG No VO 1 Beauty and the Beast G Yes VO 311 Becket R No VO 6 Beethoven PG No J:\Videos\Video_list_Alpha.doc 9/11/08 VO 160 Bells of St. Mary’s NR No VO 20 Beverly Hills Cop R No VO 79 Big PG No VO 163 Big Bear NR No VO 289 Blackbeard, The Pirate R No VO 118 Blue Hawaii NR No VO 290 Border Cop R No VO 63 Breakfast at Tiffany's NR No VO 180 Bridget Jones’ Diary R No VO 183 Broadcast News R No VO 254 Brokeback Mountain R No VO 199 Bruce Almighty Pg-13 No VO 77 Butch Cassidy and the Sun Dance Kid PG No VO 158 Bye Bye Blues PG No VO 164 Call of the Wild PG No VO 291 Captain Kidd R No VO 94 Casablanca -

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

![1 [27] Ficvaldivia 2 [27] Ficvaldivia 3 [27] Ficvaldivia 4 [27] Ficvaldivia 5](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7781/1-27-ficvaldivia-2-27-ficvaldivia-3-27-ficvaldivia-4-27-ficvaldivia-5-317781.webp)

1 [27] Ficvaldivia 2 [27] Ficvaldivia 3 [27] Ficvaldivia 4 [27] Ficvaldivia 5

[27] FICVALDIVIA 1 [27] FICVALDIVIA 2 [27] FICVALDIVIA 3 [27] FICVALDIVIA 4 [27] FICVALDIVIA 5 [27] FICVALDIVIA Palabras6 9 Words FILMES DE INAUGURACIÓN Filmes de inauguración 26 Opening films Y CLAUSURA OPENING AND CLOSING Filmes de clausura 28 FEATURES P. 25 Closing films Cortometraje de Ceremonia de Premiación 30 Awards Ceremony Short Film JURADO Y ASESORES 33 JURY AND ADVISORS P.33 EN COMPETENCIA Selección Oficial Largometraje Internacional 45 IN COMPETITION Official International Feature Selection P. 44 Selección Oficial Largometraje Chileno 59 Official Chilean Feature Selection Selección Oficial Largometraje Juvenil 67 Internacional Official International Youth Feature Selection Selección Oficial Cortometraje 75 Latinoamericano Official Latin-American Short Film Selection Selección Oficial Cortometraje Infantil 89 Latinoamericano Official Latin-American Children’s Short Film Selection Selección Oficial Cine Chileno del Futuro 96 Future Chilean Cinema Official Selection [27] FICVALDIVIA 7 MUESTRA PARALELA CINEASTAS EN FOCO 105 Video y Estallido Social 178 PARALLEL PROGRAM FILMMAKERS IN THE Video and Social Uprising P. 105 SPOTLIGHT MUESTRA CINE 185 Ana Poliak 106 RETROSPECTIVA RETROSPECTIVE PROGRAM Colectivo Los Hijos 112 Clásicos 186 Latinas a la vanguardia 122 Classics Guillaume Brac 131 VHS Erótico 190 Erotic VHS MUESTRA CINE 139 CONTEMPORÁNEO Vazofi: Bazofi en Valdivia 193 CONTEMPORARY CINEMA Vazofi: Bazofi in Valdivia PROGRAM Gala 140 PÁSATE UNA PELÍCULA 201 Gala WHAT’S YOUR STORY! HOMENAJES 146 Largometrajes familiares 202 TRIBUTES -

9782873404178 01.Pdf

SOMMAIRE Jean-François Rauger : La douceur Fuller L’ŒUVRE Thanatos Pierre Gabaston. La fureur Fuller Serge Chauvin. Crever l’écran. Une esthétique du surgissement Sarah Ohana. Faire face. À propos du style de Samuel Fuller Laurent Le Forestier. Samuel Fuller, cinéaste responsable Jean-Marie Samocki. Le chaos comme le chant. Samuel Fuller metteur en son Éros Murielle Joudet. La violence en partage Patrice Rollet. L’autre visage de la fureur. Érotique de Fuller Figures humaines Sergio Toffetti. Le jaune, le rouge, le noir et le blanc Chris Fujiwara. Les visages asiatiques de Samuel Fuller Jean-Marie Samocki. Le vieillissement de Lee Marvin. It Tolls for Thee / The Big Red One Simon Laperrière. Une grande mêlée. Les romans de Samuel Fuller LES FILMS Gilles Esposito. L’enfer du développement. Samuel Fuller scénariste Marcos Uzal. La Passion du traître. I Shot Jesse James / J’ai tué Jesse James Laura Laufer. L’Amour, vaste territoire The Baron of Arizona / Le Baron de l’Ari- zona Mathieu Macheret. Le Théâtre des opérations. The Steel Hemlet / J’ai vécu l’en- fer de Corée et Fixed Bayonets !/Baïonnette au canon Bernard Eisenschitz. Park Row / Violence à Park Row Murielle Joudet. Pickpocket. Pickup on South Street / Le Port de la drogue Samuel Bréan. Anatomie d’un mensonge. Le doublage de Pickup on South Street Jean-François Rauger. Le Sous-marin et les Rouges. Hell and High Water / Le Démon des eaux troubles The Steel Helmet. Egdardo Cozarinsky. House of Bamboo / La Maison de Bambou Bernard Benoliel. Fuller, l’attendrisseur. Run of the Arrow / Le Jugement des Jean-François Rauger flèches Jean-François Rauger. -

OLI BIGALKE | BIOGRAPHY | 25.09.2021 Oli Bigalke | CV

OLI BIGALKE | BIOGRAPHY www.spiel-kind.com | 25.09.2021 Oli Bigalke | CV FEATURE | TELEVISION 2021 | Operation Totems | TV series | Director: Jérôme Salle | Gaumont Productions | Amazon Prime Video 2020 | Der Palast | TV series | Director: Uli Edel | Constantin Television | ZDF | mini series 2020 | Der Pfad | feature film | Director: Tobias Wiemann | Eyrie Entertainment 2020 | Die Drei von der Müllabfuhr - "Die Streunerin" | TV series | Director: Hagen Bogdanski | Bavaria Fiction | ARD/Degeto 2020 | Soko Wismar - "Wolfstod" | TV series | Director: Sascha Thiel | Cinecentrum Berlin | ZDF 2020 | Der Alte - "Einer von Euch" | TV series | Director: Christoph Stark | Neue Münchner Fernsehproduktion | ZDF 2019 | Morden im Norden - "Romeo und Julia" | TV series | Director: Michi Riebl | ndF | ARD 2019 | Curveball | feature film | Director: Johannes Naber | Bon Voyage Film 2018-2019 | Preis der Freiheit | TV movie | Director: Michael Krummenacher | Wiedemann & Berg | ZDF | 3 parts 2018 | Tatort München - "One Way Ticket" | TV series | Director: Rupert Henning | Roxy Film | ARD 2018 | Die Jungen Ärzte | TV series | Director: Franziska Hörisch | Saxonia Media | ARD 2018 | Dark 2 | TV series | Director: Baran Bo Odar | Wiedemann & Berg | Netflix 2018 | Spreewaldkrimi - "Zeit der Wölfe" | TV series | Director: Pia Strietmann | Aspekt Telefilm | ZDF 2018 | Friesland - "Hand und Fuß" | TV series | Director: Isabel Prahl | Warner Bros. Television | ZDF 2018 | Kalte Füße | feature film | Director: Wolfgang Groos | Claussen+Putz Filmproduktion 2017 | Letzte -

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP on SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 Min)

January 27, 2009 (XVIII:3) Samuel Fuller PICKUP ON SOUTH STREET (1953, 80 min) Directed and written by Samuel Fuller Based on a story by Dwight Taylor Produced by Jules Schermer Original Music by Leigh Harline Cinematography by Joseph MacDonald Richard Widmark...Skip McCoy Jean Peters...Candy Thelma Ritter...Moe Williams Murvyn Vye...Captain Dan Tiger Richard Kiley...Joey Willis Bouchey...Zara Milburn Stone...Detective Winoki Parley Baer...Headquarters Communist in chair SAMUEL FULLER (August 12, 1912, Worcester, Massachusetts— October 30, 1997, Hollywood, California) has 53 writing credits and 32 directing credits. Some of the films and tv episodes he directed were Street of No Return (1989), Les Voleurs de la nuit/Thieves After Dark (1984), White Dog (1982), The Big Red One (1980), "The Iron Horse" (1966-1967), The Naked Kiss True Story of Jesse James (1957), Hilda Crane (1956), The View (1964), Shock Corridor (1963), "The Virginian" (1962), "The from Pompey's Head (1955), Broken Lance (1954), Hell and High Dick Powell Show" (1962), Merrill's Marauders (1962), Water (1954), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), Pickup on Underworld U.S.A. (1961), The Crimson Kimono (1959), South Street (1953), Titanic (1953), Niagara (1953), What Price Verboten! (1959), Forty Guns (1957), Run of the Arrow (1957), Glory (1952), O. Henry's Full House (1952), Viva Zapata! (1952), China Gate (1957), House of Bamboo (1955), Hell and High Panic in the Streets (1950), Pinky (1949), It Happens Every Water (1954), Pickup on South Street (1953), Park Row (1952), Spring (1949), Down to the Sea in Ships (1949), Yellow Sky Fixed Bayonets! (1951), The Steel Helmet (1951), The Baron of (1948), The Street with No Name (1948), Call Northside 777 Arizona (1950), and I Shot Jesse James (1949). -

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven

Spetters Directed by Paul Verhoeven Limited Edition Blu-ray release (2-disc set) on 2 December 2019 From legendary filmmaker Paul Verhoeven (Robocop, Basic Instinct) and screenwriter Gerard Soeteman (Soldier of Orange) comes an explosive, fast-paced and thrilling coming- of-age drama. Raw, intense and unabashedly sexual, Spetters is a wild ride that will knock the unsuspecting for a loop. Starring Renée Soutendijk, Jeroen Krabbé (The Fugitive) and the late great Rutger Hauer (Blade Runner), this limited edition 2-disc set (1 x Blu-ray & 1 x DVD) brings Spetters to Blu-ray for the first time in the UK and is a must own release, packed with over 4 hours of bonus content. In Spetters, three friends long for better lives and see their love of motorcycle racing as a perfect way of doing it. However the arrival of the beautiful and ambitious Fientje threatens to come between them. Special features Remastered in 4K and presented in High Definition for the first time in the UK Audio commentary by director Paul Verhoeven Symbolic Power, Profit and Performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Spetters (2019, 17 mins): audiovisual essay written and narrated by Amy Simmons Andere Tijden: Spetters (2002, 29 mins): Dutch TV documentary on the making of Spetters, featuring the filmmakers, cast and critics of the film Speed Crazy: An Interview with Paul Verhoeven (2014, 8 mins) Writing Spetters: An Interview with Gerard Soeteman (2014, 11 mins) An Interview with Jost Vacano (2014, 67 mins): wide ranging interview with the film’s cinematographer discussing his work on films including Soldier of Orange and Robocop Image gallery Trailers Illustrated booklet (***first pressing only***) containing a new interview with Paul Verhoeven by the BFI’s Peter Stanley, essays by Gerard Soeteman, Rob van Scheers and Peter Verstraten, a contemporary review, notes on the extras and film credits Product details RRP: £22.99 / Cat.