Contesting the Flow of the Milwaukee River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Lake Sturgeon Habitat in the Milwaukee River Using Side-Scan Sonar

Mapping Lake Sturgeon Habitat in the Milwaukee River Using Side-Scan Sonar Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources 2018 Office of Great Waters Grant & 2018 River Protection Planning Grant RP30818 Draft Final Reports 2018 Fund for Lake Michigan Grant # 20180479 Draft Final Report Prepared By: Andrew Struck, Matt Aho, Ryan Miller, Angela Richter, Natalie Cotter, Brittany Hahn, and Cassie Avery Ozaukee County Planning and Parks Department 121 W. Main Street Port Washington, WI 53074 June 30, 2021 Table of Contents Overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Background ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Review of Existing Efforts ........................................................................................................................ 4 Fish Passage Remediation Efforts............................................................................................................. 7 Project Description ...................................................................................................................................... 13 Remote Analysis of the Milwaukee River .............................................................................................. 13 Habitat Evaluation ................................................................................................................................. -

Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan

Village of Grafton Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan 2020 - 2024 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VILLAGE BOARD PLAN COMMISSION Jim Brunnquell, President Jim Brunnquell, Chair David Antoine, Trustee David Liss, Trustee Lisa Uribe Harbeck, Trustee Carl Harms, Member Thomas Krueger, Trustee Alan Kletti, Member David Liss, Trustee Mark Paschke, Member Susan Meinecke, Trustee Randy Silasiri, Member James Miller, Trustee PARKS AND RECREATION BOARD VILLAGE STAFF Meg Canepa, Chair Jesse Thyes, Village Administrator Lisa Uribe Harbeck, Trustee John Safstrom, Parks and Recreation Director Thomas Krueger, Trustee Jessica Wolff, Community Development Director James Miller, Trustee Charlie Donohue, Administrative Secretary II Steve Nauta, Member Mark Slaminski, Member Jodie Wolf, Senior Center Representative Park and Open Space Plan i ii Village of Grafton, WI TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ................................................................................................ 3 HISTORY OF GRAFTON ................................................................................................ 4 GENERAL REGIONAL CONTEXT .................................................................................. 5 POPULATION TRENDS AND FORECASTS ................................................................... 7 DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS ............................................................................................. -

Milwaukee Urban Water Trail

MILWAUKEE URBAN WATER TRAIL A Canoe and Kayak Guide City of Milwaukee, as seen from the Menomonee River. (Friends of Milwaukee’s Rivers) The Milwaukee Urban Water Trail IS A CANOE & KAYAK ROUTE THROUGH URBAN Planning for a Safe Trip Although the Milwaukee Urban Water Trail is not as remote PORTIONS OF THE MILWAUKEE, MENOMONEE, AND KINNICKINNIC RIVERS – WITH MORE as many popular water trail routes, the power and unpredict- ability of the Milwaukee, Menomonee, and Kinnickinnic riv- THAN 25 MILES OF PADDLING. THE TRAIL ENHANCES PUBLIC RECREATIONAL OPPORTUNI- ers should never be underestimated! It is important to plan ahead before launching. Be aware of water levels, potential TIES, PROMOTES SAFE AND LEGAL RIVER ACCESS, AND ENCOURAGES STEWARDSHIP. hazards, and required and recommended portages. ilwaukee’s Rivers – Past and Present atural Attractions M Milwaukee’s rivers have always been im- N Our local rivers flow through lands that are both pri- Water Levels and Hazards portant cultural, economic, and natural pathways. vately and publicly owned, with most of the latter protected Water levels and flow can vary greatly with rainfall, affect- Native Americans used these water routes for by the Milwaukee County Parks system and other munici- ing safety both on the land and water. Higher water gener- trade and transportation, and sustained themselves pal parks. These parks provide a scenic backdrop along ally increases level of difficulty due to low bridges, snags, with the fish, wildlife, wild rice, and other plants much of the water trail, as well as provide excellent oppor- concealed boulders, low hanging trees, and other hazards. -

Milwaukee River Greenway Master Plan

Milwaukee River Greenway Master Plan A Vision for Recreation and Restoration June 2010 Prepared by Plunkett Raysich Architects Milwaukee River Work Group a project of the Milwaukee Environmental Consortium Master Plan Team Easements Sub-committee Ann Brummitt, Milwaukee River Work Group Ann Brummitt, Milwaukee River Work Group Vince Bushell, River Revitalization Foundation Lindsay Fathallah, Godfrey & Kahn Kim Forbeck, Urban Ecology Center Kim Gleffe, River Revitalization Foundation Kim Gleffe, River Revitalization Foundation Barbara Gurican, Godfrey & Kahn Therese Gripentrog, WI Department of Natural Resources Ken Leinbach, Urban Ecology Center Barbara Gurican, Godfrey and Kahn Sarah Horn, City of Milwaukee Ray Isaacs, UWM, SARUP Habitat Sub-committee Ann Brummitt, Milwaukee River Work Group Mark Keane, UWM, SARUP Owen Boyle, Department of Natural Resources Linda Keane, Chicago Art Institute Gary Casper, UWM Field Station Terri Kinis, Riverside Park Neighborhood Association Gail Epping Overholt, UW-Extension Nik Kovac, 3rd District Alderman Kim Forbeck, Urban Ecology Center Tory Kress, Redevelopment Authority City of Milwaukee Charles Hagner, Birder’s World Magazine Ken Leinbach, Urban Ecology Center Terri Kinis, Riverside Park Neighborhood Association Richard Maslowski, City of Glendale Martha Lunz, Glendale Resident Cheryl Nenn, Milwaukee Riverkeeper Harold Schmidt, Friends of Estabrook Park Jeff Obirek, National Park Service Joel Springsteen, Urban Ecology Center Ramsey Radakovich, Milwaukee County Parks Brian Russart, Milwaukee County -

Final Community Involvement Plan

Final Community Involvement Plan Solvay Coke and Gas Site Milwaukee, Wisconsin Prepared for: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Prepared by: APEX Direct, Inc. April 2008 Contract No. EP-S5-07-01, Task Order No. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 OVERVIEW OF COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT PLAN 1 2.0 SITE OVERVIEW 1 2.1 Site Description 1 2.2 Site History and Cleanup 3 2.3 Site Contaminants 4 3.0 COMMUNITY BACKGROUND 4 3.1 Community Profile 4 3.2 Community History 5 3.3 Past Community Involvement With the Site 5 4.0 COMMUNITY CONCERNS AND QUESTIONS 5 4.1 Site Ownership 5 4.2 Site Redevelopment and Future Use 6 4.3 Economic Effects 6 4.4 Length of Time to Conduct the Cleanup 7 4.5 Cost and Responsibility for the Cleanup 7 4.6 Possible Lake Contamination 7 4.7 Health Effects 7 4.8 Site Access and Security 8 5.0 COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT ACTIVITIES 8 5.1 Establish a Point of Contact 8 5.2 Develop and Maintain a Site Mailing List 9 5.3 Establish an Information Repository 9 5.4 Maintain Contact With Local Officials, Organizations and Residents 9 5.5 Maintain Communication With Local Media 9 5.6 Prepare and Distribute Written Information 10 5.7 Make Information Available Electronically 10 5.8 Conduct Public Meetings or Information Sessions 10 5.9 Publish Announcements 10 5.10 Revise the Community Involvement Plan 10 APPENDIXES A INFORMATION REPOSITORY AND POSSIBLE MEETING LOCATIONS B LIST OF CONTACTS AND INTERESTED GROUPS C COMMUNITY INTERVIEW QUESTIONS i 1.0 Overview of Community Involvement Plan The U.S. -

Case 19-11740 Doc 1 Filed 08/05/19 Page 1 of 22

Case 19-11740 Doc 1 Filed 08/05/19 Page 1 of 22 Fill in this information to identify your case: United States Bankruptcy Court for the: DISTRICT OF DELAWARE Case number (if known) Chapter 11 Check if this an amended filing Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy 4/19 If more space is needed, attach a separate sheet to this form. On the top of any additional pages, write the debtor's name and case number (if known). For more information, a separate document, Instructions for Bankruptcy Forms for Non-Individuals, is available. 1. Debtor's name iPic Media LLC 2. All other names debtor used in the last 8 years Include any assumed DBA See Rider 1 names, trade names and doing business as names 3. Debtor's federal Employer Identification 61-1740150 Number (EIN) 4. Debtor's address Principal place of business Mailing address, if different from principal place of business 433 Plaza Real, Suite 335 Boca Raton, FL 33432 Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code P.O. Box, Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code Palm Beach Location of principal assets, if different from principal County place of business Number, Street, City, State & ZIP Code 5. Debtor's website (URL) www.ipic.com 6. Type of debtor Corporation (including Limited Liability Company (LLC) and Limited Liability Partnership (LLP)) Partnership (excluding LLP) Other. Specify: Official Form 201 Voluntary Petition for Non-Individuals Filing for Bankruptcy page 1 Case 19-11740 Doc 1 Filed 08/05/19 Page 2 of 22 Debtor iPic Media LLC Case number (if known) Name 7. -

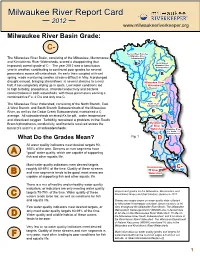

2012 River Report Card

Milwaukee River Report Card 2012 www.milwaukeeriverkeeper.org Milwaukee River Basin Grade: C- East and West Branches Milwaukee River The Milwaukee River Basin, consisting of the Milwaukee, Menomonee, Subwatershed and Kinnickinnic River Watersheds, scored a disappointing (but North Branch improved) overall grade of C-. The year 2012 was a tumultuous B+ Milwaukee River Subwatershed year in weather, contributing to continued poor grades for several parameters across all watersheds. An early thaw coupled with wet B spring, made monitoring swollen streams difficult in May. A prolonged drought ensued, bringing streamflows in several streams to a near Milwaukee River halt, if not completely drying up in spots. Low water conditions led Watershed to high turbidity, phosphorus, chloride/conductivity and bacteria concentrations in both watersheds, with these parameters earning a combined five F’s, 2 D’s and only one C. C The Milwaukee River Watershed, consisting of the North Branch, East Cedar Creek Subwatershed & West Branch, and South Branch Subwatersheds of the Milwaukee River, as well as the Cedar Creek Subwatershed, maintained a C B average. All subwatersheds received A’s for pH, water temperature and dissolved oxygen. Turbidity remained a problem in the South Branch phosphorus, conductivity, and bacteria received across the Menomonee C- River board D’s and F’s in all subwatersheds. Watershed Milwaukee River South Subwatershed What Do the Grades Mean? Fig. 1 D All water quality indicators meet desired targets 90- 100% of the time. Streams or river segments have A “good” water quality, which are capable of supporting fish and other aquatic life. Most water quality indicators meet desired targets Kinnickinnic C- roughly 80-89% of the time. -

Water Quality Monitoring on the Little Menomonee River System

Water Quality Monitoring in Ozaukee County Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources River Protection Planning Grant RP31018 Final Report Prepared By: Ozaukee County Planning and Parks Department 121 W. Main Street Port Washington, WI 53074 June 30, 2020 Draft Final Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Project Objectives ................................................................................................................................. 10 Monitoring Design ................................................................................................................................ 10 Monitoring Locations ............................................................................................................................ 11 Methods ................................................................................................................................................ 16 General Water Quality Sampling Method Requirements & Quality Assurance/Quality Control .......... 16 Discrete Water Quality Sampling Methods ........................................................................................ 16 Continuous Water Quality Sampling Methods ................................................................................... 18 Additional Data Collection ................................................................................................................ 20 Section -

Shorewood, WI

Chemistry in Place Experience Placemaking: Shorewood, WI Welcome to Shorewood, Wisconsin! Shorewood is a unique community just north of downtown Milwaukee. Located in Milwaukee County, this small village offers Lake Michigan views, a delicious variety of dining options, shops with distinctive clothing, and amazing art and architecture. Shorewood constantly works to beautify and improve the small area it takes up along Lake Michigan. The village was originally incorporated in 1900, making it the fourth oldest suburb in the Milwaukee area. Change is a constant theme in this progressive village that’s rooted in the past. The historical charm mixed with the progressive nature of the village makes it a destination for all ages. Photo credit: Rand McNally Photo credit: Rand McNally Shorewood in a Nutshell Population: 13,337 (2013) Land area: 1.591 mi² Walkability score: 87 Explore Shorewood , Wisconsin! www.chemistryinplace.net Experience Placemaking: Shorewood, WI 1 of 4 Chemistry in Place Shorewood Shorewood is just minutes from downtown Milwaukee, yet offers conveniences such as boutique clothing stores, hair salons, fitness stores and gyms. Pamper yourself and feel your best, as Shorewood will surely make you feel this way. You won’t go hungry in Shorewood with over 35 food and beverage places to choose from – sushi, pizza, sandwiches, fish, or coffee and a cupcake are all options! Enjoy tasty wine or several different craft beers with friends and family for dinner or evening toasts. www.chemistryinplace.net Experience Placemaking: Shorewood, WI 2 of 4 Chemistry in Place Lake Michigan is just minutes away from Shorewood. A stop at Atwater Park & Beach overlooking Lake Michigan is fun for all ages. -

Milwaukee.Pdf

Coast to Coast, Nation to Nation, BridgeStreet Worldwide No matter where business takes you, finding quality extended stay housing should never be an issue. That’s because there’s BridgeStreet. With thousands of fully furnished corporate apartments spanning the globe, BrideStreet provides you with everything you need, where you need it – from New York, Washington D.C., and Toronto to London, Paris, and everywhere else. Call BridgeStreet today and let us get to know what’s essential to your extended stay 1.800.B.SSTEET We’re also on the Global Distribution System (GDS) and adding cities all the time. Our GDS code is BK. Chek us out. WWW.BRIDGESTREET.COM WORLDWIDE 1.800.B.STREET (1.800.278.7338) ® UK 44.207.792.2222 FRANCE 33.142.94.1313 CANADA 1.800.667.8483 TTY/TTD (USA & CANADA) 1.888.428.0600 CORPORATE HOUSING MADE EASY ™ More than just car insurance. GEICO can insure your motorcycle, ATV, and RV. And the GEICO Insurance Agency can help you fi nd homeowners, renters, boat insurance, and more! ® Motorcycle and ATV coverages are underwritten by GEICO Indemnity Company. Homeowners, renters, boat and PWC coverages are written through non-affi liated insurance companies and are secured through the GEICO Insurance Agency, Inc. Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. Government Employees Insurance Co. • GEICO General Insurance Co. • GEICO Indemnity Co. • GEICO Casualty Co. These companies are subsidiaries of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. GEICO: Washington, DC 20076. GEICO Gecko image © 1999-2010. © 2010 GEICO NEWMARKET SERVICES ublisher of 95 U.S. -

History of Ozaukee County

OZAUKEE COUNTY www.co.ozaukee.wi.us History of Ozaukee County By Don Silldorff, Director, Mequon Historical Society Copyright © 1998 Other than one or two transient fur traders the only residents of Ozaukee County before 1835, were Potawatomi and Menominee Indians. The land comprising Ozaukee County was part of Milwaukee County, Michigan Territory. In 1835 Michigan Territory was in the midst of petitioning Congress to become a state. One of the requirements was for Michigan to assist Wisconsin in becoming a separate territory. The U.S. Government moved the process along in 1835 by advertising land for public sale in Wisconsin, prompting thousands of New Englanders to come to Wisconsin to purchase the cheap land at $1.25 per acre. They traveled by way of the Erie Canal to Buffalo, New York and then by way of the Great Lakes on ships to Wisconsin where they found bountiful land and new business opportunities. The early history of Ozaukee County before Wisconsin became a separate territory in 1836 is a separate story which began with native Americans, explorers, fur traders and military activity. Before the white man occupied the land, travel through the heavily forested wilderness was by canoe on the rivers and streams and by foot on the many Indian trails that threaded their way throughout the land. One of these trails, used for thousands of years, extended from Hudson Bay all the way to Florida. A portion of this trail connected Fort Howard at Green Bay with Fort Dearborn in Chicago, and became known as the Green Bay Trail. -

Greater Milwaukee Water Quality Connections INTRODUCTION CONTENTS the Waters of Southeastern Wisconsin Have Always Been Among Its Most Important and Cherished Assets

GREATER MILWAUKEE WATER QUALITY CONNECTIONS INTRODUCTION CONTENTS The waters of Southeastern Wisconsin have always been among its most important and cherished assets. Long before the first pioneers came, Native Americans depended on the abundant game in the watershed for food and trading. These early inhabitants Introduction 2 gave the area the name “Milwaukee” which means “Gathering Place by the Waters.” Rural 5 The first European immigrants were fur traders who recognized the strategic advantage of a fur trading post on the shores of Lake Suburban 9 Michigan. As Milwaukee grew, so did the importance of water resources. The port of Milwaukee grew to be the largest in the Urban 15 state, helping the “Gathering Place by the Waters” become Wisconsin’s largest city. Breweries became famous partly due to the Lake Michigan 21 purity of the water supply. Upstream communities flourished within the basin, damming rivers for power. Visions and Next Steps 25 The fast growth took its toll on our water resources. The once pristine streams and lakes were choked with waste that alarmed Contacts and Resources 26 residents. In 1972, public indignation turned into action when Congress responded to their concerns about water pollution with the passage of the Clean Water Act, which promised to make waters “fishable and swimmable” by 1983. EDITORIAL More than 30 years have passed since the adoption of the Clean Water Act. We have made great progress, but still fall short of the goal Kate Morgan Editor/Lead Writer of “fishable and swimmable” waters. Flooding, non-point pollution, and sewer overflows continue to degrade water quality.