MAINELAND a F I L M B Y M I a O W a N G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jason Schwartzman Elisabeth Moss Jonathan Pryce Krysten Ritter Joséphine De La Baume Listen up Philip a Film by Alex Ross Perry

Jason Schwartzman Elisabeth Moss Jonathan Pryce Krysten Ritter Joséphine de La Baume Listen Up Philip a film by Alex Ross Perry Following up his critically acclaimed THE COLOR WHEEL, Alex Ross Perry scripts a complex, intimate and highly idiosyncratic comedy filled withNew Yorkers living their lives somewhere between individuality and isolation. Jason Schwartzman leads an impressive cast including Elisabeth Moss, Krysten Ritter and Jonathan Pryce, balancing Perry’s quick-witted dialogue and their characters’ painful, personal truths. With narration by Eric Bogosian, we switch perspectives as seasons and attitudes change, offering a literary look into the lives of these individuals and the triumph of reality over the human spirit. Listen Up Philip was produced by Washington Square Films (the company’s follow-up film to the acclaimed All Is Lost) and Sailor Bear Productions, the team behind the 2013 Sundance hit Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. SYNOPSIS Anger rages in Philip (Jason Schwartzman) as he awaits the publication of his sure-to-succeed second novel. He feels pushed out of his adopted home city by the constant crowds and noise, a deteriorating relationship with his photographer girlfriend Ashley (Elisabeth Moss), and his own indifference to promoting the novel. When Philip’s idol Ike Zimmerman (Jonathan Pryce) offers his isolated summer home as a refuge, he finally gets the peace and quiet to focus on his favorite subject – himself. Philip faces mistakes and miseries affecting those around him, including his girlfriend, her sister, his idol, his idol’s daughter, and all the ex-girlfriends and enemies that lie in wait on the open streets of New York. -

Le Laboratoire D'éric Rohmer, Un Cinéaste À La

2 EXPOSITIONS ÉVÉNEMENTS 25 CYCLES EXCEPTIONNELS : BLAKE E DWARDS / N ANNI MORETTI FRITZ LANG / CITÉS FUTURISTES / ROBERT ALTMAN / JACQUES FEYDER BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI / TIM BURTON / EGYPTOMANIA / ALAIN CAVALIER BULLE OGIER / GABRIEL YARED / KING HU / SHIRLEY MACLAINE / STEVEN SPIELBERG ... Organisez votre saison sur cinematheque.fr LA CINÉMATHÈQUE FRANÇAISE - 51 RUE DE BERCY 75012 - PARIS Grands mécènes de La Cinémathèque française pub_cf_belfort_2011.indd 1 25/10/2011 17:40:32 Le cinéma n’est pas une distraction pour moi. C’est la rencontre, parfois atroce, avec mes désirs les plus profonds. Alejandra Pizarnik 25 janvier 1963 (Journaux 1959-1971, collection Ibériques, édtions José Corti, 2010) 3 L’équipe du festival Remerciements Président du Festival : Étienne Butzbach Le festival remercie ses partenaires : Le Festival remercie particulièrement Déléguée générale, directrice artistique : la Région Franche-Comté, le Conseil général du Jean-Pierre Chevènement Catherine Bizern Territoire de Belfort, le ministère de la Culture Françoise Etchegaray, Patricia Mazuy, Jean- Secrétaire générale : Michèle Demange et de la communication, la Direction régionale Claude Brisseau Adjoint à la direction artistique, catalogue, site des Affaires culturelles de Franche-Comté, Hala Abdallah, Michel Amarger, Jérôme internet : Christian Borghino le Centre national du cinéma et de l’image Baptizet, Gilles Barthélémy, Xavier Baert, Claire Sélection de la compétition officielle : animée, la Cinémathèque française, la Sempat, Beaudoin, Bernard Benoliel, Vincent-Paul -

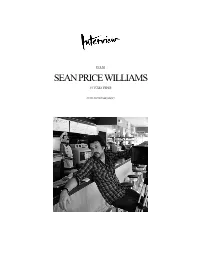

SEAN PRICE WILLIAMS Director of Photography

SEAN PRICE WILLIAMS Director of Photography FEATURES – Selected Credits TESLA Michael Almereyda Intrinsic Value Films HER SMELL Alex Ross Perry Bow and Arrow Entertainment Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2019) Official Selection, Toronto International Film Festival (2018) Official Selection, New York Film Festival (2018) TWO AGAINST NATURE Owen Kline Scott Rudin Prod / Elara Pictures GOOD TIME Ben and Joshua Safdie A24 Official Selection, Cannes Film Festival (2017) Nominated, Best Feature, Gotham Awards (2017) GOLDEN EXITS Alex Ross Perry Washington Square Films Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2017) Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2017) MARJORIE PRIME Michael Almereyda Film Rise / Passage Pictures Winner, Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize, Sundance Film Festival (2017) THIRST STREET Nathan Silver Washington Square Films Official Selection, Tribeca Film Festival (2017) QUEEN OF EARTH Alex Ross Perry IFC Films Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2015) HEAVEN KNOWS WHAT Ben & Joshua Safdie Iconoclast Nominated, John Cassavetes Award, Independent Spirit Awards (2015) Nominated, Best Feature, Gotham Awards (2015) Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, Toronto International Film Festival (2014) Winner, C.I.C.A.E. Award, Venice Film Festival (2014) CHRISTMAS, AGAIN Charles Poekel Sundance Channel Official Selection, New Directors/New Films Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2015) Nominated, John Cassavetes Award, Independent Spirit Awards (2015) SIN -

Kate Plays Christine

Presents Kate Plays Christine ** U.S. Documentary Special Jury Award for Writing** 110 Minutes / English / USA WORLD SALES CONTACT: PRESS CONTACT: ANA VICENTE YUNG KHA DOGWOOF DOGWOOF [email protected] [email protected] 19-23 Ironmonger Row, London, EC1V 3QN T: +442072536244 Synopsis In 1974, television host Christine Chubbuck committed suicide on air at a Sarasota, Florida, news station. This is considered the first televised suicide in history, and though it was the inspiration for the 1976 Best Picture nominee Network, the story and facts behind the event remain mostly unknown. Now in the present, actress Kate Lyn Sheil is cast in a “stylized cheap ‘70s soap opera” version of Christine’s story, and to prepare for the role, Kate travels to Sarasota to investigate the mysteries and meanings behind her tragic demise. Filmmaker Robert Greene cleverly forgoes your standard talking-head-and- sound-bite approach to nonfiction storytelling, instead choosing to employ Kate Lyn Sheil as a conduit to understanding an impossibly complex issue. Committed to doing justice to Christine’s life, Kate not only candidly pulls back the curtain on her acting process, but she also reveals the biases and presumptions even supposed experts can provide in their diagnosis. Kate Plays Christine boldly challenges its subjects and audience alike to accept that answers from the past are never easy. About Christine Chubbuck Chubbuck was born in Hudson, Ohio, the daughter of Margaretha D. "Peg" (1921–1994) and George Fairbanks Chubbuck (1918–2015). She had two brothers, Greg and Tim. WXLT-TV owner, Bob Nelson, had initially hired Chubbuck as a reporter but later gave her a community affairs talk show, Suncoast Digest, which ran at 9:00 am. -

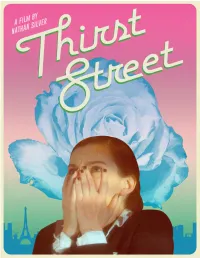

Thirst Street Press-Notes-Web.Pdf

A PSYCHOSEXUAL BLACK COMEDY Press Contacts: Kevin McLean | [email protected] Kara MacLean | [email protected] USA/FRANCE / 2017 / 83 minutes / English with French Subtitles / Color / DCP + Blu-ray Alone and depressed after the suicide of her lover, American flight attendant Gina (Lindsay Burdge, A TEACHER) travels to Paris and hooks up with nightclub bartender Jerome (Damien Bonnard, STAYING VERTICAL) on her layover. But as Gina falls deeper into lust and opts to stay in France, this harmless rendezvous quickly turns into unrequited amour fou. When Jerome’s ex Clémence (Esther Garrel) reenters the picture, Gina is sent on a downward spiral of miscommunication, masochism, and madness. Inspire by European erotic dramas from the 70’s, THIRST STREET burrows deep into the delirious extremes we go to for love. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT THIRST STREET brings together two of my longest-standing, most nagging obsessions: France and Don Quixote. I spent my junior year of high school as an exchange student in France, in a foolish attempt to live out my dream of being a French poet. I realized within days that I wasn’t French (and never would be) and that poetry wasn’t for me, but nearly two decades later, I still find myself just as obsessed with the place. Our protagonist Gina is my Quixote, unflinching in her quest to find that most important (and ridiculous) thing: love. The emotions of THIRST STREET are just as hysterical as those in my last few movies, but the style here is much more fluid and deliberate, with surreal lighting increasingly threatening to devour the picture. -

Bamcinématek Announces the Full Lineup for the Ninth Annual

BAMcinématek announces the full lineup for the ninth annual BAMcinemaFest, a festival of American independent films with 24 New York premieres, one North American and three world premieres, Jun 14—25 Opening night—New York premiere of Aaron Katz’s Gemini Closing night—New York premiere of Alex Ross Perry’s Golden Exits Centerpiece— World premiere of Jim McKay’s En el Séptimo Día Spotlight—New York premieres of David Lowery’s A Ghost Story & Gillian Robespierre’s Landline Outdoor screening—Jim McKay’s Our Song (2000) in Brooklyn Bridge Park The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinemaFest, BAMcinématek, and BAM Rose Cinemas. May 3, 2017/Brooklyn, NY—BAMcinématek announces the full lineup for the ninth annual BAMcinemaFest (Jun 14—25), hailed as “The New York film festival for independent films” (The New Yorker). A 12-day festival presenting premieres of emerging voices in American independent cinema, this year’s lineup features 24 New York premieres, one North American premiere, and three world premieres. The Wall Street Journal is proud once again to join BAMcinemaFest as the title sponsor. “I’m incredibly proud of the program our team has put together,” says Gina Duncan, Associate Vice President, Cinema. “From the endearing comedy The Big Sick to the micro-budget Princess Cyd and Lemon, the audacious first feature from Janicza Bravo, the line-up truly reflects the breadth of American independent cinema today. Other highlights include the world premiere of Jim McKay’s, En el Séptimo Día an instant classic all the more powerful for its relevance, Aaron Katz’s sophisticated genre piece, Gemini, Common Carrier, a cinematic mixtape from the Bushwick based filmmaker, James N. -

Sean Price Williams

FILM SEAN PRICE WILLIAMS BY JULIA YEPES PUBLISHED 08/16/17 "I don't really have a motor inside that turns on and churns out energy to get work," says New York- based cinematographer Sean Price Williams. The staggeringly prolific director of photography has racked up an astonishing 53 film and video credits in the last seven years alone. Williams, who recently turned 40, is known for his lyrical, hallucinatory, and lush images, and his work is frequently called out by critics for his use of light and the way he makes the faces of his subjects glow. A former employee of the storied Kim's Video and Music on St. Marks Place in Manhattan, the Delaware native is known for his work with filmmakers like Alex Ross Perry, Josh and Benny Safdie, Michael Almereyda, and Albert Maysles. He's long been an underground hero for independent filmmakers and discerning cinemagoers, and a growing contingent of directors won't shut up about him. Perry, the 33-year-old writer-director whose dark comedies blend subversive wit with a literate sensibility and style, considers Williams his most important collaborator; Almereyda, the longtime independent film luminary, says the cinematographer's influence has shaped his recent work; and actor Jason Schwartzman has cited Williams as an inspiration. His top 1000 films list—which includes movies by directors like Nicholas Ray, Walerian Borowczyk, Sergei Paradjanov, Sogo Ishii, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Yuri Ilyenko, and Paul Morrissey—has circulated among cinephiles for years. (He made his first list in 2005 and updates it about every six months.) A movie-crazy teen, Williams got his first camera at age 15 and shot his first feature in 1999 while he was a college student. -

Golden Exits

Perry,GOLDEN Alex EXITS Ross 52 14036 pos: 19 _ © Sean Price Williams Golden Exits Alex Ross Perry Producer Christos V. Konstantakopoulos, Alex Ross Perry, It’s April and Naomi has come to New York from Australia to work for Nick, Adam Piotrowicz, Katie Stern, Joshua Blum, Craig Butta. an archivist cataloguing the materials belonging to his partner Alyssa’s Production companies Faliro House Productions (Athen, dead father. Nick was given the job by her sister Gwen; both are suspicious Greece), Washington Square Films (New York, USA), Bow of Nick’s preference for female assistants. Naomi doesn’t know anyone in & Arrow Entertainment (Los Angeles, USA), Forager Film the city apart from her childhood acquaintance Buddy. He runs his own Company (Chicago, USA), Webber Gilbert Media Group (Chicago, recording studio and employed Jess to run it; she later became his wife. USA). Written and directed by Alex Ross Perry. Director of Her best friend Sam is Gwen’s personal assistant; Gwen isn’t easy. photography Sean Price Williams. Editor Robert Greene. Naomi and Jess are in their twenties; Sam and Buddy in their thirties; Nick, Music Keegan DeWitt. Sound design Ryan M. Price. Sound Jim Alyssa and Gwen in their forties; none of them are happy. It’s there in their Morgan, Lion Thompson. Production design Fletcher Chancey, faces, captured in tight close-ups which amplify the stubborn sense of Scott Kuzio. discontent. Naomi’s arrival awakens things that could be, that might have With Emily Browning (Naomi), Adam Horovitz (Nick), Jason been, that never will be. Each generation covets the other’s privileges Schwartzman (Buddy), Chloë Sevigny (Alyssa), Mary-Louise while quietly forgetting its own. -

Eyes-Find-Eyes-Dossier-De-Presse

“If an Indian were in hiding or waiting in ambush, he’d look away if he saw a white-faced scout, because « eyes find eyes » “ Nicholas Ray Distribution : Alfama Films 176 rue du temple 75003 Paris tel: 01 42 01 84 76 | fax: 01 42 01 08 30 [email protected] www.alfamafilms.fr Presse : Claire Viroulaud Ciné-Sud Promotion 130 rue de Turenne 75003 Paris tel: 01 44 54 54 77 [email protected] Ernst, expert en oeuvres d’art, profite de sa réputation et de ses réseaux pour collaborer avec des trafiquants. Menant un double-jeu, il se retrouve pris au piège lorsqu’on lui demande de remettre la main sur L’incrédulité de Saint Thomas du Caravage. Entre Paris et New York, ses aventures et la femme qu’il aime, Ernst, qui joue sur tous les tableaux, n’arrive bientôt plus à distinguer le vrai du faux. Quel prix accorder à une oeuvre d’art ? C’est tout naturellement qu’ils ont décidé de Une fois authentifiée, l’oeuvre d’art prend place sur le s’associer à nouveau sur ce film, tourné entre Paris marché. Cette sacralisation provoque aussi son trafic et New York. Tout le projet s’est donc fait à deux : et ses ratés. Voir le faussaire Van Meegeren. Lire les de la réalisation à la musique, tous les postes ont colonnes de faits divers, l’attentat de la galerie des été partagés (le son excepté). Idem pour l’image Offices de Florence, ou encore cette mère qui pour : initialement prévue uniquement en 16mm, la protéger son fils, détruisit les oeuvres qu’il avait partie parisienne a été finalement tournée en volées… Se peut-il donc que certains n’accordent HDcam. -

Download EPK (PDF)

mainelandfilm.com MAINELAND a f i l m b y m i a o w a n g SXSW Documentary Feature Competition (WINNER - Special Jury Award) Independent Film Festival of Boston (WINNER - Special Jury Award) New Hampshire Film Festival (WINNER - Audience Choice Award) WINNER WINNER SPECIAL JURY AWARD AUDIENCE CHOICE AWARD 2017 FORMAT CONTACT 90 min | HD | Color | 5.1 and Stereo Miao Wang [email protected] / 929.500.1453 Mandarin Chinese and English mainelandfilm.com 2017 | China/USA facebook/twitter: @mainelandfilm | instagram: @threewatersfilms A Three Waters Production SHORT SYNOPSIS Filmed over three years in China and the U.S., MAINELAND is a multi-layered coming-of-age tale that follows two affluent and cosmopolitan teenagers as they settle into a boarding school in blue-collar rural Maine. Part of the enormous wave of “parachute students” from China enrolling in U.S. private schools, bubbly, fun-loving Stella and introspective Harry come seeking a Western-style education, escape from the dreaded Chinese college en- trance exam, and the promise of a Hollywood-style U.S. high school experience. As Stella and Harry’s fuzzy visions of the American dream slowly gain more clarity, they ruminate on their experiences of alienation, culture clash, and personal identity, sharing new understandings and poignant discourses on home and country. LONG SYNOPSIS With China’s ascendance, there has been an exponential surge of study-abroad students — Chinese students now account for over one-third to one-half of international secondary school students. Many are children of the new Chinese wealthy elite, whose parents found success in China’s economic rise of the last decades. -

SEAN PRICE WILLIAMS Director of Photography

SEAN PRICE WILLIAMS Director of Photography FEATURES – Selected Credits TWO AGAINST NATURE Owen Kline Scott Rudin Prod / Elara Pictures GOLDEN EXITS Alex Ross Perry Washington Square Films Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2017) Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2017) GOOD TIME Ben and Joshua Safdie A24 Official Selection, In Competition, Cannes Film Festival (2017) Nominated, “Best Feature”, Gotham Awards (2017) MARJORIE PRIME Michael Almereyda Film Rise / Passage Pictures Winner, Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film Prize, Sundance Film Festival (2017) THIRST STREET Nathan Silver Washington Square Films Official Selection, Tribeca Film Festival (2017) QUEEN OF EARTH Alex Ross Perry IFC Films Official Selection, Berlin Film Festival (2015) HEAVEN KNOWS WHAT Ben & Joshua Safdie Iconoclast Nominated, John Cassavetes Award, Independent Spirit Awards (2015) Nominated, “Best Feature”, Gotham Awards (2015) Official Selection, SXSW Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, Toronto International Film Festival (2014) Winner, C.I.C.A.E. Award, Venice Film Festival (2014) CHRISTMAS, AGAIN Charles Poekel Sundance Channel Official Selection, New Directors/New Films Film Festival (2015) Official Selection, Sundance Film Festival (2015) Nominated, John Cassavetes Award, Independent Spirit Awards (2015) SIN ALAS Ben Chace Franklin Avenue Films Nominated, Best Film, Los Angeles Film Festival (2015) LISTEN UP PHILLIP Alex Ross Perry Washington Square Films Winner, Special Jury Prize, Locarno International Film Festival (2014) Official Selection, -

'Her Smell' Review: Elisabeth Moss Is One of the Most Noxious Movie

‘Her Smell’ Review: Elisabeth Moss Is One of the Most Noxious Movie Characters of All Time in Brave and Rewarding Punk Epic TIFF: Alex Ross Perry's intimate punk epic dares you to walk out from the moment it starts, but rewards those who stick it out to the end. David Ehrlich So about that title. It stinks. It’s pungent and rancid. “Her Smell” could have a positive connotation, but you just know that it doesn’t here. There’s a hostility to it, like an odorous barrier you’d have to get through in order to reach the woman exuding it. Viewers familiar with any of Alex Ross Perry’s previous films will probably be holding their noses as they walk into this one. Newbies might want to follow suit. Perry knows what he’s doing. His work has always had the courage to be profoundly unpleasant. We’re talking about a guy whose breakthrough film (“The Color Wheel”) was a micro-budget 16mm road trip comedy that built to a sudden eruption of incest, and whose comparatively star-studded follow- ups (“Listen Up, Philip,” “Queen of Earth,” and “Golden Exits”) have shined a light on some of New York’s shittiest people. The most “likable character” in his entire body of work is a cat named Gadzookey. But if all of Perry’s stories have been hard to stomach, “Her Smell” takes things to impressive new lows before hitting bottom and tunneling out through the other side. It’s truly one of the most noxious movies ever made, which might help to explain why it’s also Perry’s best.