Polyvinylchloride, Phthalates and Packaging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vinyl Chloride

Withdrawn Provided for Historical Reference Only VINYL CHLORIDE Method no.: 04 Matrix: Air Target concentration: 1 ppm (2.5 mg/m3) (OSHA PEL) Procedure: Collection on charcoal (two-tubes in-series) , desorption with carbon disulfide, analysis by gas chromatography with a flame ionization detector. Stored in refrigerator and analyzed as soon as possible. Detection limit based on recommended air volume: 0.25 ppm Recommended air volume and sampling rate: 1 L at 0.05 L/min Standard error of estimate at the target concentration: 7.6% (Figure 4.1.) Status of method: Recommended by NIOSH, partially evaluated by OSHA Laboratory. Date:WITHDRAWN April 1979 Chemist: Dee R. Chambers Organic Methods Evaluation Branch OSHA Analytical Laboratory Salt Lake City Utah Note: OSHA no longer uses or supports this method (December 2019). Withdrawn Provided for Historical Reference Only 1. General Discussion 1.1. Background 1.1.1. History In January 1974, B.F. Goodrich Chemical Company informed NIOSH of several deaths among polyvinyl chloride production workers from angiosarcoma, a rare liver cancer. In response to this and other evidence of potential hazards, OSHA lowered the workplace air standard for vinyl chloride (VC) from 500 ppm to 1 ppm 8-h time weighted average. Since the recognition that VC was a carcinogen, a great deal of research into the sampling and analytical methodology has been conducted. Perhaps the most complete and thorough examination has been conducted by Hill, McCammon, Saalwaechter, Teass, and W oodfin for NIOSH titled "The Gas Chromatographic Determination of Vinyl Chloride in Air Samples Collected on Charcoal" (Ref. 5.1.). -

162 Part 175—Indirect Food Addi

§ 174.6 21 CFR Ch. I (4–1–19 Edition) (c) The existence in this subchapter B Subpart B—Substances for Use Only as of a regulation prescribing safe condi- Components of Adhesives tions for the use of a substance as an Sec. article or component of articles that 175.105 Adhesives. contact food shall not be construed as 175.125 Pressure-sensitive adhesives. implying that such substance may be safely used as a direct additive in food. Subpart C—Substances for Use as (d) Substances that under conditions Components of Coatings of good manufacturing practice may be 175.210 Acrylate ester copolymer coating. safely used as components of articles 175.230 Hot-melt strippable food coatings. that contact food include the fol- 175.250 Paraffin (synthetic). lowing, subject to any prescribed limi- 175.260 Partial phosphoric acid esters of pol- yester resins. tations: 175.270 Poly(vinyl fluoride) resins. (1) Substances generally recognized 175.300 Resinous and polymeric coatings. as safe in or on food. 175.320 Resinous and polymeric coatings for (2) Substances generally recognized polyolefin films. as safe for their intended use in food 175.350 Vinyl acetate/crotonic acid copoly- mer. packaging. 175.360 Vinylidene chloride copolymer coat- (3) Substances used in accordance ings for nylon film. with a prior sanction or approval. 175.365 Vinylidene chloride copolymer coat- (4) Substances permitted for use by ings for polycarbonate film. 175.380 Xylene-formaldehyde resins con- regulations in this part and parts 175, densed with 4,4′-isopropylidenediphenol- 176, 177, 178 and § 179.45 of this chapter. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 4,481,333 Fleischer Et Al

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 4,481,333 Fleischer et al. 45 Date of Patent: Nov. 6, 1984 54 THERMOPLASTIC COMPOSITIONS 58 Field of Search ................................ 525/192, 199 COMPRISING WINYL CHLORIDE POLYMER, CLPE AND FLUOROPOLYMER 56) References Cited U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS 75) Inventors: Dietrich Fleischer, Darmstadt; Eckhard Weber, Liederbach; 3,005,795 10/1961 Busse et al. ......................... 525/199 3,294,871 2/1966 Schmitt et al. ...... 52.5/154 X Johannes Brandrup, Wiesbaden, all 3,299,182 1/1967 Jennings et al. ... ... 525/192 of Fed. Rep. of Germany 3,334,157 8/1967 Larsen ..................... ... 525/99 73 Assignee: Hoechst Aktiengesellschaft, Fed. 3,940,456 2/1976 Fey et al. ............................ 525/192 Rep. of Germany Primary Examiner-Carman J. Seccuro (21) Appl. No.: 566,207 Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Connolly & Hutz 22 Filed: Dec. 28, 1983 57 ABSTRACT 30 Foreign Application Priority Data The invention relates to a thermoplastic composition which comprises vinyl chloride polymers and chlori Dec. 31, 1982 (DE Fed. Rep. of Germany ....... 3248.731 nated polyethylene and which contains finely divided 51) Int. Cl. ...................... C08L 23/28; C08L 27/06; fluoropolymers and has a markedly improved process C08L 27/18 ability, particularly when shaped by extrusion. 52 U.S. C. .................................... 525/192; 525/199; 525/239 7 Claims, No Drawings 4,481,333 2 iaries and do not provide a solution to the present prob THERMOPLASTC COMPOSITIONS lem. COMPRISINGVINYL CHLORIDE POLYMER, -

Recent Attempts in the Design of Efficient PVC Plasticizers With

materials Review Recent Attempts in the Design of Efficient PVC Plasticizers with Reduced Migration Joanna Czogała 1,2,3,* , Ewa Pankalla 2 and Roman Turczyn 1,* 1 Department of Physical Chemistry and Technology of Polymers, Silesian University of Technology, Strzody 9, 44-100 Gliwice, Poland 2 Research and Innovation Department, Grupa Azoty Zakłady Azotowe K˛edzierzynS.A., Mostowa 30A, 47-220 K˛edzierzyn-Ko´zle,Poland; [email protected] 3 Joint Doctoral School, Silesian University of Technology, Akademicka 2A, 44-100 Gliwice, Poland * Correspondence: [email protected] (J.C.); [email protected] (R.T.) Abstract: This paper reviews the current trends in replacing commonly used plasticizers in poly(vinyl chloride), PVC, formulations by new compounds with reduced migration, leading to the enhance- ment in mechanical properties and better plasticizing efficiency. Novel plasticizers have been divided into three groups depending on the replacement strategy, i.e., total replacement, partial replacement, and internal plasticizers. Chemical and physical properties of PVC formulations containing a wide range of plasticizers have been compared, allowing observance of the improvements in polymer per- formance in comparison to PVC plasticized with conventionally applied bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, di-n-octyl phthalate, bis(2-ethylhexyl) terephthalate and di-n-octyl terephthalate. Among a variety of newly developed plasticizers, we have indicated those presenting excellent migration resistance and advantageous mechanical properties, as well as those derived from natural sources. A separate chapter has been dedicated to the description of a synergistic effect of a mixture of two plasticizers, primary and secondary, that benefits in migration suppression when secondary plasticizer is added to PVC blend. -

Preventing Harm from Phthalates, Avoiding PVC in Hospitals

Preventing Harm from Phthalates, Avoiding PVC in Hospitals Karolina Ruzickova • Madeleine Cobbing • Mark Rossi • Thomas Belazzi Authors: Karolina Růžičková Madeleine Cobbing Mark Rossi, PhD. Thomas Belazzi, PhD. Acknowledgments: We would like to express our thanks to those who have contributed to the medical devices analysis and the content of the report: Prof. Ing. Bruno Klausbrückner, Vienna Hospital Association, Austria. Patricia Cameron and Friederike Otto, BUND – Friends of the Earth, Germany. Sonja Haider, Women in Europe for Common Future, Germany. Angelina Bartlett, Germany. Dorothee Lebeda, Germany. Aurélie Gauthier, CNIID, France. Lenka Mašková, Arnika, Czech Republic. Lumír Kantor, MD, Faculty Hospital Olomouc, Czech Republic. Juan Antonio Ortega García, Children’s Hospital La Fe, Spain. Malgorzata Kowalska, 3R, Poland. Anne Marie Vass, Karolinska University Hospital, Sweden. Åke Wennmalm, MD, PhD, Stockholm County Council, Sweden. Magnus Hedenmark, MSc., Sweden. We are deeply indebted to those have reviewed the report: Ted Schettler MD, MPH, Science and Environmental Health Network, USA. Charlotte Brody, RN and Stacy Malkan, Health Care Without Harm, USA. Sanford Lewis, Attorney, USA. And Dr.Čestmír Hrdinka, Health Care Without Harm, Czech Republic. We would also like to thank to Štěpán Bartošek and Štěpán Mamula for the design and production of the report and Stefan Gara for providing pictures. Preventing Harm from Phthalates, Avoiding PVC in Hospitals Heath Care Without Harm June 2004 Authors: Karolina Růžičková, Madeleine Cobbing, Mark Rossi, PhD., Thomas Belazzi, PhD. © 2004 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................... 4 From Foetus to Toddler: Exposure to DEHP during a Critical Period of Development ........... 5 The Toxicity of DEHP DEHP Exposure during Specifi c Medical Treatment Therapies Results from Analytical Survey of Phthalates in Medical Products......................................... -

Photo-Stabilizers Utilizing Ibuprofen Tin Complexes Against Ultraviolet Radiation

Article A Surface Morphological Study, Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Photo-Stabilizers Utilizing Ibuprofen Tin Complexes against Ultraviolet Radiation Baraa Watheq 1, Emad Yousif 1,* , Mohammed H. Al-Mashhadani 1, Alaa Mohammed 1 , Dina S. Ahmed 2, Mohammed Kadhom 3 and Ali H. Jawad 4 1 Department of Chemistry, College of Science, Al-Nahrain University, 64021 Baghdad, Iraq; [email protected] (B.W.); [email protected] (M.H.A.-M.); [email protected] (A.M.) 2 Department of Medical Instrumentation Engineering, Al-Mansour University College, 64021 Baghdad, Iraq; [email protected] 3 Department of Renewable Energy, College of Energy and Environmental Science, Alkarkh University of Science, 64021 Baghdad, Iraq; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam 40450, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23 August 2020; Accepted: 9 October 2020; Published: 13 October 2020 Abstract: In this work, three Ibuprofen tin complexes were synthesized and characterized by Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), 1H and 119Sn-Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), and Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopies to identify the structures. The complexes were mixed separately with poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) to improve its photo-stability properties. Their activity was demonstrated by several approaches of the FTIR to exhibit the formation of new groups within the polymer structure due to the exposure to UV light. Moreover, the polymer’s weight loss during irradiation and the average molecular weight estimation using its viscosity before and after irradiation were investigated. Furthermore, different techniques were used to study the surface morphology of the PVC before and after irradiation. -

Selected Plasticisers and Additional Sweeteners in the Nordic Environment Selected Plasticisers and Additional Sweeteners in the Nordic Environment

TemaNord 2013:505 TemaNord Ved Stranden 18 DK-1061 Copenhagen K www.norden.org Selected Plasticisers and Additional Sweeteners in the Nordic Environment Selected Plasticisers and Additional Sweeteners in the Nordic Environment The report Selected plasticisers and additional sweeteners in the Nordic Environment describes the findings of a Nordic environmental study. The study has been done as a screening, that is, it provides a snapshot of the occurrence of selected plasticisers and sweeteners, both in regions most likely to be polluted as well as in some very pristine environments. The pla- sticisers analysed were long chained phthalates and adipates, and the sweeteners analysed were aspartame, cyclamate and sucralose. The purpose of the screening was to elucidate levels and pathways of hitherto unrecognized pollutants. Thus the samples analysed were taken mainly from sewage lines, but also in recipients and biota, both in assumed hot-spot areas and in background areas. TemaNord 2013:505 ISBN 978-92-893-2464-9 ISBN 978-92-893-2464-9 9 789289 324649 TN2013505 omslag.indd 1 18-02-2013 10:25:36 Selected Plasticisers and Additional Sweeteners in the Nordic Environment Mikael Remberger, Lennart Kaj, Katarina Hansson, Hanna Andersson and Eva Brorström-Lundén, IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, Helene Lunder and Martin Schlabach, NILU, Norwegian Institute for Air Research TemaNord 2013:505 Selected Plasticisers and Additional Sweeteners in the Nordic Environment Mikael Remberger, Lennart Kaj, Katarina Hansson, Hanna Andersson and Eva Brorström-Lundén, IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, Helene Lunder and Martin Schlabach, NILU, Norwegian Institute for Air Research ISBN 978-92-893-2464-9 http://dx.doi.org/10.6027/TN2013-505 TemaNord 2013:505 © Nordic Council of Ministers 2013 Layout: Hanne Lebech/NMR Cover photo: Image Select Print: Rosendahls-Schultz Grafisk Copies: 150 Printed in Denmark This publication has been published with financial support by the Nordic Council of Ministers. -

Common Chemical Additives in Plastics

Journal of Hazardous Materials 344 (2018) 179–199 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Hazardous Materials j ournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhazmat Review An overview of chemical additives present in plastics: Migration, release, fate and environmental impact during their use, disposal and recycling a,∗ a,∗ b a a John N. Hahladakis , Costas A. Velis , Roland Weber , Eleni Iacovidou , Phil Purnell a School of Civil Engineering, University of Leeds, Woodhouse Lane, LS2 9JT, Leeds, United Kingdom b POPs Environmental Consulting, Lindenfirststr. 23, D.73527, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany h i g h l i g h t s g r a p h i c a l a b s t r a c t • Plastics are important in our society providing a range of benefits. • Waste plastics, nowadays, burden the marine and terrestrial environment. • Additives and PoTSs create complica- tions in all stages of plastics lifecycle. • Inappropriate use, disposal and recy- cling may lead to undesirable release of PoTSs. • Sound recycling of plastics is the best waste management and sustainable option. a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Over the last 60 years plastics production has increased manifold, owing to their inexpensive, multipur- Received 22 July 2017 pose, durable and lightweight nature. These characteristics have raised the demand for plastic materials Received in revised form 2 October 2017 that will continue to grow over the coming years. However, with increased plastic materials production, Accepted 7 October 2017 comes increased plastic material wastage creating a number of challenges, as well as opportunities to Available online 9 October 2017 the waste management industry. -

Vinyl Chloride CAS#: 75-01-4

PUBLIC HEALTH STATEMENT Vinyl Chloride CAS#: 75-01-4 Division of Toxicology and Environmental Medicine July 2006 This Public Health Statement is the summary breathing, eating, or drinking the substance, or by chapter from the Toxicological Profile for Vinyl skin contact. Chloride. It is one in a series of Public Health Statements about hazardous substances and their If you are exposed to vinyl chloride, many factors health effects. A shorter version, the ToxFAQs™, will determine whether you will be harmed. These is also available. This information is important factors include the dose (how much), the duration because this substance may harm you. The effects (how long), and how you come in contact with it. of exposure to any hazardous substance depend on You must also consider any other chemicals you are the dose, the duration, how you are exposed, exposed to and your age, sex, diet, family traits, personal traits and habits, and whether other lifestyle, and state of health. chemicals are present. For more information, call the ATSDR Information Center at 1-888-422-8737. 1.1 WHAT IS VINYL CHLORIDE? _____________________________________ Vinyl chloride is known also as chloroethene, This public health statement tells you about vinyl chloroethylene, ethylene monochloride, or chloride and the effects of exposure to it. monochloroethylene. At room temperature, it is a colorless gas, it burns easily, and it is not stable at The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) high temperatures. Vinyl chloride exists in liquid identifies the most serious hazardous waste sites in form if kept under high pressure or at low the nation. These sites are then placed on the temperatures. -

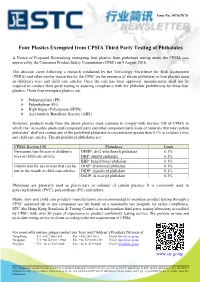

Four Plastics Exempted from CPSIA Third Party Testing of Phthalates

Issue No.: 05/16/TCD Four Plastics Exempted from CPSIA Third Party Testing of Phthalates A Notice of Proposed Rulemaking exempting four plastics from phthalates testing under the CPSIA was approved by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) on 9 August 2016. The decision came following a research conducted by the Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment (TERA) and other similar researches by the CPSC on the presence of eleven phthalates in four plastics used in children’s toys and child care articles. Once the rule has been approved, manufacturers shall not be required to conduct third-party testing in assuring compliance with the phthalate prohibitions for these four plastics. These four exempted plastics are: ¾ Polypropylene (PP) ¾ Polyethylene (PE) ¾ High Impact Polystyrene (HIPS) ¾ Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) However, products made from the above plastics must continue to comply with Section 108 of CPSIA in which the “accessible plasticized component parts and other component parts made of materials that may contain phthalates” shall not contain any of the prohibited phthalates in concentration greater than 0.1% in children’s toys and child care articles. The six prohibited phthalates are: CPSIA Section 108 Phthalates Limit Permanent ban for use in children’s DEHP: di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate 0.1% toys or child care articles DBP: dibutyl phthalate 0.1% BBP: benzyl butyl phthalate 0.1% Interim ban for use in toys that can be DINP: diisononyl phthalate 0.1% put in the mouth or child care articles DIDP: diisodecyl phthalate 0.1% DnOP: di-n-octyl phthalate 0.1% Phthalates are generally used as plasticizers or softener of certain plastics. -

State of Dibutyl Phthalate Molecules in Plasticized Poly(Vinyl Chloride)*

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kazan Federal University Digital Repository Polymer Science U.S.S.R. Vol. 20, pp. 1492-1498. 0932-3950/78/9601-1492507.50]0. (~) Pergamon Press Ltd. 1979. Printed in Poland. STATE OF DIBUTYL PHTHALATE MOLECULES IN PLASTICIZED POLY(VINYL CHLORIDE)* A. ~. ~AkKLAKOV, A. A. I~¢[AKLAKOV, A. N. TEMlqIKOV and B. F. TEPLOV V. I. Lenin State University, Kazan V. A. Kargin Polymer Chemistry and Technology Research Institute J (Received 22 August 1977) It was found that the rotational motion of plasticizer molecules in the polymer matrix is hindered, the degree of hindrance differing for different molecules. With " use of the data on the dibutyl phthalate (DBP) autodiffusion it" was possible to evaluate the lifetime of the PVC-plasticizer solvates. This lifetime is a function of the amount of small molecules and of temperature. The solvatation in these systems is of the dynamic type. The "free" plasticizer is absent in samples containing 30-52 wt. °/o DBP. The measurements were made by the pulse NMR method. SEVERAL investigations have been reported in connection with the state of plasticizer molecules introduced into polymer [1]. However, the problem has yet to be fully resolved. In some cases use of the NMR method allows separate evalua- tion of the mobility of macromolecules and molecules of a low molecular substance and it appears that the use of NMR may provide additional information on the mode of behaviour of molecules of components forming part of plasticized sys- tems. -

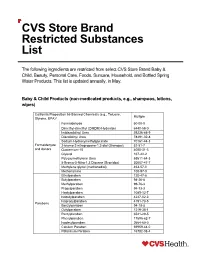

CVS Store Brand Restricted Substances List

CVS Store Brand Restricted Substances List The following ingredients are restricted from select CVS Store Brand Baby & Child, Beauty, Personal Care, Foods, Suncare, Household, and Bottled Spring Water Products. This list is updated annually, in May. Baby & Child Products (non-medicated products, e.g., shampoos, lotions, wipes) California Proposition 65 Banned Chemicals (e.g., Toluene, Multiple Styrene, BPA) ii Formaldehyde 50-00-0 Dimethyl-dimethyl (DMDM) Hydantoin 6440-58-0 Imidazolidinyl Urea 39236-46-9 Diazolidinyl Urea 78491-02-8 Sodium Hydroxymethylglycinate 70161-44-3 Formaldehyde 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol (Bronopol) 52-51-7 and donors Quaternium-15 4080-31-3 Glyoxal 107-22-2 Polyoxymethylene Urea 68611-64-3 5-Bromo-5-Nitro-1,3 Dioxane (Bronidox) 30007-47-7 Methylene glycol (methanediol) 463-57-0 Methenamine 100-97-0 Ethylparaben 120-47-8 Butylparaben 94-26-8 Methylparaben 99-76-3 Propylparaben 94-13-3 Heptylparaben 1085-12-7 Isobutylparaben 4247-02-3 Isopropylparaben 4191-73-5 Parabens Benzylparaben 94-18-8 Octylparaben 1219-38-1 Pentylparaben 6521-29-5 Phenylparaben 17696-62-7 Isodecylparaben 2664-60-0 Calcium Paraben 69959-44-0 Potassium Paraben 16782-08-4 5026-62-0 35285-69-9 Sodium Parabens 35285-68-8 36457-20-2 Hexamidine Paraben Not Found Hexamidine Diparaben 93841-83-9 Undecylenoyl PEG 5 Paraben Not Found Phenoxyethylparaben 55468-88-7 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid 99-96-7 Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) 117-81-7 Benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP) 85-68-7 Di-n-butyl phthalate (DBP) 84-74-2 Diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP) 26761-40-0