The History of Our Lord in Works of Art (Mrs. Jameson)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christ Crowned with Thorns PTC Article

From Quaternities to the Quintessence - exploring the early 16C painting 1 'Christ Crowned with Thorns' by Hieronymus Bosch Dr Pamela Tudor Craig http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/hieronymus-bosch-christ-mocked-the-crowning-with-thorns At first sight, it is hard to believe that Hieronymus Bosch’s painting of ‘Christ Crowned with Thorns’ in the National Gallery, London 1 could have come from the brush that stirred up a thousand and one nightmare images. Bosch is synonymous with the bizarre: his very name conjures up a world of hellish fantasy. Yet this paradoxically serene moment, frozen from the story of Christ’s Passion, has none of the frenzy we normally associate with his painting. This picture is the calm ‘eye in the hurricane’ of Bosch’s turbulent work. The striking imagery of Bosch’s paintings provokes an immediate emotional reaction, but our intellectual response is largely inhibited by the painter’s enigmatic iconography, which confronts the modern mind with a mass of confusing riddles. In his vocabulary of visual expression, Bosch is the most remote of the five artists considered in this book. Although his style has affinities with other painters, it cannot be said to belong to any particular school. Bosch’s individuality was the product of a fertile imagination working largely in isolation: a narrow life led in a provincial city largely untouched by the cultural mainstream of the Low Countries. Hieronymus Bosch lived in the city of S’Hertogenbosch 2, the capital of the North Brabant region of the Low Countries. He was born into the van Aken family who had been painters there for at least three generations. -

HNA Apr 2015 Cover.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 32, No. 1 April 2015 Peter Paul Rubens, Agrippina and Germanicus, c. 1614, oil on panel, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Andrew W. Mellon Fund, 1963.8.1. Exhibited at the Academy Art Museum, Easton, MD, April 25 – July 5, 2015. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Amy Golahny (2013-2017) Lycoming College Williamsport PA 17701 Vice-President – Paul Crenshaw (2013-2017) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Treasurer – Dawn Odell Lewis and Clark College 0615 SW Palatine Hill Road Portland OR 97219-7899 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Obituary/Tributes ................................................................. 1 Lloyd DeWitt (2012-2016) Stephanie Dickey (2013-2017) HNA News ............................................................................7 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Personalia ............................................................................... 8 Walter Melion (2014-2018) Exhibitions ........................................................................... -

Religious Imagery of the Italian Renaissance

Religious Imagery of the Italian Renaissance Structuring Concepts • The changing status of the artist • The shift from images and objects that are strictly religious to the idea of Art • Shift from highly iconic imagery (still) to narratives (more dynamic, a story unfolding) Characteristics of Italian Images • Links to Byzantine art through both style and materials • References to antiquity through Greco-Roman and Byzantine cultures • Simplicity and monumentality of forms– clearing away nonessential or symbolic elements • Emphasizing naturalism through perspective and anatomy • The impact of the emerging humanism in images/works of art. TIMELINE OF ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: QUATROCENTO, CINQUECENTO and early/late distinctions. The Era of Art In Elizabeth’s lecture crucifixex, she stressed the artistic representations of crucifixions as distinct from more devotional crucifixions, one of the main differences being an attention paid to the artfulness of the images as well as a break with more devotional presentations of the sacred. We are moving steadily toward the era which Hans Belting calls “the Era of Art” • Artists begin to sign their work, take credit for their work • Begin developing distinctive styles and innovate older forms (rather than copying) • A kind of ‘cult’ of artists originates with works such as Georgio Vasari one of the earliest art histories, The Lives of the Artists, which listed the great Italian artists, as well as inventing and developing the idea of the “Renaissance” Vasari’s writing serves as a kind of hagiography of -

Loans in And

LOANS TO THE NATIONAL GALLERY April 2016 – March 2017 The following pictures were on loan to the National Closson The Cascade at Tivoli (currently on Michallon A Tree Gallery between April 2016 and March 2017 loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Nittis Winter Landscape *Pictures returned Probably by Coignet River Landscape Pitloo View of the Aventine Hill from the Palatine Probably by Constantin Bridge at Subiaco Pitloo Vines at Báia (currently on loan to the ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST / Probably by Corot Staircase in the Entrance Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN to the Villa of Maecenas at Tivoli Reinagle Mountainous Landscape with Ruins Fra Angelico Blessing Redeemer Costa After a Shower near Pisa (currently on and Buildings Gentile da Fabriano The Madonna and Child loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Reinagle Rome: Part of the Aurelian Wall with Angels (The Quaratesi Madonna) Costa Porto d’Anzio (currently on loan to (the Muro Torto) with the Villa Ludovisi Gossaert Adam and Eve the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) beyond (currently on loan to the Leighton Cimabue’s Celebrated Madonna is carried Danby A Boat-Builder’s Yard Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) in Procession through the Streets of Florence Degas Promenade beside the Sea Reinagle A Trout Stream Pesellino Saints Mamas and James Denis Cliff at Vicovaro (currently on loan Probably by Rosa Wooded Bank with Figures to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) Schelfhout Landscape with Cumulus Clouds, with THE WARDEN AND FELLOWS Denis A Torrent at Tivoli (currently on loan View of Haarlem on -

An Expanded View of the Forms and Functions of 15Th-Century Netherlandish Devotional Art

SEEKING THE PERSONAL: AN EXPANDED VIEW OF THE FORMS AND FUNCTIONS OF 15TH-CENTURY NETHERLANDISH DEVOTIONAL ART By BRENNA FRANCES BRALEY A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Brenna Frances Braley ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank the members of my committee, John L. Ward and Robin Poynor, for all of their help and encouragement while working on this project. I also thank Julie Kauffman, Johanna Kauffman, Bonnie Hampton, and Jody Berman (for their technological assistance), Joshua Braley, Linda Braley, and Rance Braley (for their help as proofreaders), and all the rest of my friends and family (for their unending patience and moral support). iii TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii LIST OF FIGURES .............................................................................................................v ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................1 2 HISTORICAL AND THEOLOGICAL CONTEXT....................................................5 3 THE PHYSICAL AND THE SPIRITUAL ................................................................26 4 RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE AND -

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Discoveries

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 7 Issue 1 218-225 12-4-2019 Discoveries Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation . "Discoveries." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 7, 1 (2019): 218-225. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol7/iss1/15 This Discoveries is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. et al. ____________________PEREGRINATIONS_______________ JOURNAL OF MEDIEVAL ART AND ARCHITECTURE VOLUME VII, NUMBER 1 (AUTUMN 2019) Discoveries 'Magnificent' baptismal font discovered at Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity, Palestinian officials say An ancient 1,500-year-old, 6th - century baptismal font has been discovered on June 22, 2019, during renovation work at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. In a news conference earlier this week, Ziad al- Bandak, head of the committee tasked with restoring the famous church, announced that archaeologists had discovered a baptismal font (a basin of water used for baptisms) dating to the 6th or 7th century hidden inside another, older baptismal font. The newly discovered font appears to be made of the same sort of stone as the church's columns, meaning it could be nearly as old as the church itself, which dates to the 4th century. Re-written from https://www.livescience.com/65826-jesus-birthplace-baptismal-fonts- found.html and https://www.foxnews.com/science/baptismal-font-discovered- bethlehem-church-of-the-nativity 218 Published by Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange, 2019 Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture, Vol. -

Center 34 National Gallery of Art Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Center34

CENTER 34 CENTER34 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART CENTER FOR IN STUDY THE ADVANCED VISUAL ARTS CENTER34 CENTER34 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Record of Activities and Research Reports June 2013 – May 2014 Washington, 2014 National Gallery of Art CENTER FOR ADVANCED STUDY IN THE VISUAL ARTS Washington, DC Mailing address: 2000B South Club Drive, Landover, Maryland 20785 Telephone: (202) 842-6480 Fax: (202) 842-6733 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.nga.gov/casva Copyright © 2014 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law, and except by reviewers from the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Produced by the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts and the Publishing Office, National Gallery of Art, Washington ISSN 1557-198x (print) ISSN 1557-1998 (online) Editor in Chief, Judy Metro Deputy Publisher and Production Manager, Chris Vogel Series Editor, Peter M. Lukehart Center Report Coordinator, Hayley Plack Managing Editor, Cynthia Ware Design Manager, Wendy Schleicher Assistant Production Manager, John Long Assistant Editor, Lisa Wainwright Designed by Patricia Inglis, typeset in Monotype Sabon and Helvetica Neue by BW&A Books, Inc., and printed on McCoy Silk by C&R Printing, Chantilly, Virginia Frontispiece: Members of Center, December 17, 2013 -

Summary for Bellini, Giovanni, C. 1430/1435-1516

KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE Bellini, Giovanni, c. 1430/1435-1516 IDENTIFIER NAM0107 NATIONALITY Venetian BIRTH DATE 1425 DEATH DATE 1516 EXTERNAL LINKS UNION LIST OF ARTIST NAMES RECORD http://vocab.getty.edu/page/ulan/500019244 VIRTUAL INTERNATIONAL AUTHORITY FILE RECORD http://viaf.org/viaf/100161245 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS NAME AUTHORITY FILE RECORD http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n50007140 WIKIPEDIA https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_Bellini 18 RELATED ART OBJECTS K1080 Alvise Vivarini Portrait of a Man K357 Vincenzo Catena Portrait of Giambattista Memmo NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, DC, GALLERY ARCHIVES Page 1 KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE K594 Venetian 16th Century Pagan Rite, A K1628 Giovanni Bellini An Episode from the Life of Publius Cornelius Scipio K413 Attributed to Giovanni Bellini Giovanni Emo K1077 Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child K479 Workshop of Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child in a Landscape NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, DC, GALLERY ARCHIVES Page 2 KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE K1244 Follower of Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child with Saints K467 Giovanni Bellini Portrait of a Venetian Gentleman K331 Giovanni Bellini Portrait of a Young Man K406 Giovanni Bellini Saint Jerome Reading K1659 Giovanni Bellini The Infant Bacchus NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, DC, GALLERY ARCHIVES Page 3 KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE K1212 Follower of Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child in a Landscape K1710 Attributed to Giovanni Bellini Bearded Man, A K1904 Giovanni Bellini and Vincenzo Catena Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Peter K1905 Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child K2188 Giovanni Bellini Madonna and Child NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, DC, GALLERY ARCHIVES Page 4 KRESS COLLECTION DIGITAL ARCHIVE K389 Giovanni Bellini Saint Luke and Saint Albert of Sicily RECORD LINK https://kress.nga.gov/Detail/entities/NAM0107 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, DC, GALLERY ARCHIVES Page 5. -

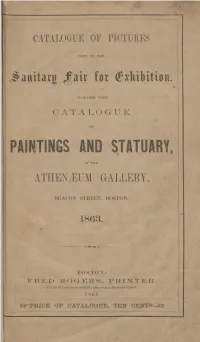

Paintings and Statuary

().11' PICTURES Lf{SP 'P" '1'III: !'xIttbtttOtt. (1ittttt4tt1) ýý'ý`lit' 1vOt' 'I'l l(il: 'I'IIIiH \\'1'1'11 CA TAL () G UI], OF PAINTINGSAND STATUARY, (111' rill" A'1'HENNIEUlVIGALLERY, lil'; A(Y)N ti'['REET, BOSTON. 1.8(i3. liUs1'0 N: F1- t i,: I) N. 1.s: 1 NV ýwinr, r- 1TIt1: F.'P, ggmeito t1Le Old South CLurrh. , 18 113. Wh-PRICE OF CATALOGUE, TEN CENTS-91 7- COMMMEE. JAbIFS COllMAN. MLSSiiS. _lI. '° EDWARD PEIRKINS. _X. GEORGE W. WALE"S. (6 B. S. ROTCII. 44 C. F. SIIIMMIN. DIRECTOR-J. HARVEY YOUNG. STATUARY. Nos. Subjects. Owners. 1 Copy of the Head of Apollo Belvidere. Dlrs. II. Greenough. 2 Bust of Raphael. Presented by Hon. T. 11. Perkins. Athena um. 3 Bust. R. S. Greenough. 4 Hobe Ganymede, by T. G. Crawford. C. C. Perkins. and " 5 Statue of Ceres. 6 Bust of Rubens. Presented by Hen. T. IL Perkins. Athenaeum. 7 Bust of a Vestal, by Canova. C. C. Perkins. 8 Cast of the Laoroön. Atliena; um. 9 Bust of a Child, by T. Ball. 10 Bust of W. Allston, by Clevenger. Athenaeum. 11 Anacreon, by Crawford. Athenaeum. 12 Cast of the Apollo Belvidere. Athenamin. 13 Bas-relief, CGSperauza, " by W. W. Story. 14 Bust of Judge Story, by W. W. Story. 15 Statue of a Venue at the Bath. Athenaeum. 16 Cast of the Statue of Diana hunting. Athenaeum. 17 Bas-relief. Athenaeum. 18 Bust of Napoleon. Mrs. 11. Greenough 19 Cast from the Statue of the Vatican Mercury. Athenaeum. " The god appears standing, with a characteristic inclination of the head, musingly regard- ing the affairs of mortals. -

P20-21 Layout 1

20 Established 1961 Lifestyle Features Sunday, October 27, 2019 n early Renaissance painting by the Italian with Two Angels” at the National Gallery in having been displayed right above a cooking master Cimabue goes under the hammer London. hotplate. Historians say only about a dozen works ASunday, a few weeks after the rare artwork The “Virgin” was valued at 6.5 million pounds on wood — all unsigned — are thought to have was found hanging in an unsuspecting elderly ($8.3 million) when it was given to the museum in been made by Cimabue, more known for his Frenchwoman’s kitchen. “Christ Mocked,” by the 2000 in lieu of inheritance taxes by a British aris- mosaics, frescoes and altarpieces. 13th-century artist also known as Cenni di Pepo, tocrat who found it while cleaning out his ances- His more natural and nuanced depictions has been valued at four to six million euros ($4.4 tral seat in Suffolk. The French painting’s elderly marked a turning point for Italian painters still to $6.7 million) for what could be France’s owner in Compiegne, northeast of Paris, thought influenced by highly stylised Byzantine art. Art biggest art sale of the year. it was just an old religious icon when she sought historians consider him a trailblazer for the cre- Art experts at Turquin in Paris used infrared an appraisal from auctioneers at Acteon, the ative Renaissance that would flourish under reflectology to confirm that the tiny unsigned house organizing the sale in nearby Senlis. greats like Giotto, one of Cimabue’s pupils. -

Queering Christ: Habitus Theology As Trans-Embodied Incarnation in Late Medieval Culture by Jonah Coman, B.A., M.Litt

Queering Christ: Habitus theology as trans-embodied incarnation in late medieval culture by Jonah Coman, B.A., M.Litt. Supervisors: Prof Vicky Gunn, Dr Anna Fisk Dissertation presented in partial fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Glasgow School of Art September 2019 Declaration I hereby declare that this research has been carried out and the thesis composed by myself, and that the thesis has not been accepted in fulfilment of the requirements of any other degree or professional qualification Dedicated to my readers, Dr Stephenie McGucken and Dr Sara Oberg Stradal, to my mentors, Prof Pat Cullum and Dr Liz Oakley-Brown, and to my supporters, Q.M, F.M and J.H. Abstract Situated at the intersection of queer theology, longitudinal research on material culture and trans studies, this thesis presents a coherent medieval theology of a transhuman incarnated Christ. This manifests both at academic/ecclesiastical levels and at lay, mystic and poetic ones. The material evidence stems from exegetical and mystical texts, sermons, lay poetry, community dramatic pageants and visual imagery from book- to architectural-scale. The accumulation of these sources results in a coherent theology associated with the incarnational technology of the sartorial habitus. The habitus theology enables both the medieval and the modern reader to encounter an incarnated Christ that dons humanity as textile. The history of the habitus thology is joined by an art-historical study of skin colour as a gendered signifier, in order to demonstrate the multiple avenues of trans- ontological visibility in medieval sources. The exploration of embodied and material devotion of the middle ages reveals possibilities of queer readings regarding gender and even ontological status of the human body. -

OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 6 December 2017

OLD MASTER PAINTINGS Wednesday 6 December 2017 For details of the charges payable in addition to the final Hammer Price of each Lot please refer to paragraphs 7 & 8 of the Notice to Bidders at the back of the catalogue. BONHAMS OLD MASTERS DEPARTMENT Andrew McKenzie Caroline Oliphant Lisa Greaves Director, Head of Department, Group Head of Pictures Department Director London London and Head of Sale London – – – Poppy Harvey-Jones Archie Parker Brian Koetser Junior Specialist Consultant Consultant London London London – – – Bun Boisseau Mark Fisher Madalina Lazen Administrator, Director, European Paintings, Senior Specialist, European Paintings London Los Angeles New York Bonhams 1793 Limited Bonhams International Board Bonhams UK Ltd Directors – – – Registered No. 4326560 Robert Brooks Co-Chairman, Colin Sheaf Chairman, Gordon McFarlan, Andrew McKenzie, Registered Office: Montpelier Galleries Malcolm Barber Co-Chairman, Harvey Cammell Deputy Chairman, Simon Mitchell, Jeff Muse, Mike Neill, Montpelier Street, London SW7 1HH Colin Sheaf Deputy Chairman, Antony Bennett, Matthew Bradbury, Charlie O’Brien, Giles Peppiatt, India Phillips, Matthew Girling CEO, Lucinda Bredin, Simon Cottle, Andrew Currie, Peter Rees, John Sandon, Tim Schofield, +44 (0) 20 7393 3900 Patrick Meade Group Vice Chairman, Jean Ghika, Charles Graham-Campbell, Veronique Scorer, Robert Smith, James Stratton, +44 (0) 20 7393 3905 fax Jon Baddeley, Rupert Banner, Geoffrey Davies, Matthew Haley, Richard Harvey, Robin Hereford, Ralph Taylor, Charlie Thomas, David Williams,