Kniga В Работу 12 01 2020.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Introduction to the Chinese Naming Tradition of Both Ming and Zi

ǂãϒZƜ 100 ě 12 , 101 Ȃ 167-188 ÚɅjΩôȖď Ȭ®d Οɳ1Zķ͵:ɓI ͻ:, Ŵ Ů ΚɎ˚ΚɎ˚jjjˆôˆôˆôϜďϜďϜďôďΚôďΚôďΚ 167 An Introduction to the Chinese Naming Tradition of Both Ming and Zi Chun-Ping Hsieh Associate Professor of General Education Center National Defense University Abstract Since ancient times, the Chinese have paid high respect to their own full names. A popular saying goes: “While sitting on the seat (or staying at the homeland), one never changes one’s surname; while walking on the road (or traveling abroad), one never changes one’s given name.” To the Chinese, a kind of sacredness lies so definitely in everyone’s name. The surname signifies the continuity of his lineage, whereas the personal name ming signifies blessings bestowed by the parents. A model gentleman of Chinese gentry, jun zi, means a person who conscientiously devotes himself to a virtuous and candid life so as symbolically not only to keep his name from being detained but also to glorify his parents as well as the lineage ancestors. To our surprise, however, the Chinese of traditional elite gentry would adopt, in addition, a courtesy name, zi, at the age of twenty. To avoid deviating from the sense of filial piety, the meaning of this courtesy name must evoke a response to that of the primary personal name. The present paper will thus focus on the strategic naming of zi as ingenious responses to ming, which discloses the most astonishingly wonderful wisdom in the art of Chinese naming. In the first place, we must understand that the need of zi cannot be separated from the address etiquette with which the Chinese of traditional hierarchical society were greatly concerned. -

Riverside Lawyer Magazine

Publications Committee Riverside Robyn Beilin Aurora Hughes Yoginee Braslaw Gary Ilmanen County Charlotte Butt Rick Lantz Mike Cappelli Richard Reed LAWYER Joshua Divine Andy Sheffield Donna Hecht Michael Trenholm James Heiting Lisa Yang CONTENTS Co-Editors ....................................................... Michael Bazzo Jacqueline Carey-Wilson Design and Production ........................ PIP Printing Riverside Cover Design ........................................ PIP Printing Riverside Columns: Officers of the Bar Association 3 ........... President’s Message by Mary Ellen Daniels President President Elect 4 ... Past President’s Message by David G. Moore Mary Ellen Daniels Michelle Ouellette tel: (909) 684-4444 tel: (909) 686-1450 18 ................... Current Affairs by Richard Brent Reed email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Vice President Chief Financial Officer Theresa Han Savage David T. Bristow tel: (909) 248-0328 tel: (909) 682-1771 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] COVER STORY: Secretary Past President Daniel Hantman Brian C. Pearcy 10 ........................ Caught in the Kosovo War tel: (909) 784-4400 tel: (909) 686-1584 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Justice James D. Ward Director-at-Large E. Aurora Hughes Jay E. Orr ................................ tel: (909) 682-3246 tel: (909) 955-5516 12 The Road to Tashkent email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Stephen G. Larson Janet A. Nakada Michael Trenholm tel: (909) 779-1362 tel: (909) 781-9231 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Executive Director Charlotte Butt, [email protected] Features: Officers of the Barristers Association 5 ................. The Lights Are Much Brighter There — Downtown Riverside President Treasurer Questions & Answers compiled by Vicki L. Broach Wendy M. -

Celebrating Nowruz in Central Asia

Arts & Traditions Along the Silk Road: Celebrating Nowruz in Central Asia Dear Traveler, Please join Museum Travel Alliance from March 12-26, 2021 on Arts & Traditions Along the Silk Road: Celebrating Nowruz in Central Asia. Observe the ancient traditions of Nowruz (Persian New Year) in Bukhara, visiting private family homes to participate in elaborate ceremonies not often seen by travelers. Join the director for exclusive, after-hours access to Gur-e-Amir, the opulent tomb of Mongol conqueror Amir Timur (Tamerlane) in Samarkand. Explore the vast archaeological site of Afrasiab, and marvel at the excavated treasures in its dedicated museum in the company of a local archaeologist. We are delighted that this trip will be accompanied by Helen Evans as our lecturer from The Metropolitan Museum of Art. This trip is sponsored by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. We expect this program to fill quickly. Please call the Museum Travel Alliance at (855) 533-0033 or (212) 302-3251 or email [email protected] to reserve a place on this trip. We hope you will join us. Sincerely, Jim Friedlander President MUSEUM TRAVEL ALLIANCE 1040 Avenue of the Americas, 23rd Floor, New York, NY 10018 | 212-302-3251 or 855-533-0033 | Fax 212-344-7493 [email protected] | www.museumtravelalliance.com BBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBBB Travel with March -

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study

The Silk Roads: an ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 The Silk Roads An ICOMOS Thematic Study by Tim Williams on behalf of ICOMOS 2014 International Council of Monuments and Sites 11 rue du Séminaire de Conflans 94220 Charenton-le-Pont FRANCE ISBN 978-2-918086-12-3 © ICOMOS All rights reserved Contents STATES PARTIES COVERED BY THIS STUDY ......................................................................... X ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... XI 1 CONTEXT FOR THIS THEMATIC STUDY ........................................................................ 1 1.1 The purpose of the study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Background to this study ......................................................................................................... 2 1.2.1 Global Strategy ................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.2 Cultural routes ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.3 Serial transnational World Heritage nominations of the Silk Roads .................................................. 3 1.2.4 Ittingen expert meeting 2010 ........................................................................................................... 3 2 THE SILK ROADS: BACKGROUND, DEFINITIONS -

Central Asia 6 Index

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd 504 Behind the Scenes SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/ privacy. OUR READERS AUTHOR THANKS Many thanks to the travellers who used Bradley Mayhew the last edition and wrote to us with help- Thanks to stalwart co-authors Tom, John, ful hints, useful advice and interesting Mark and our anonymous Turkmenistan anecdotes: author. Hard to find a more dedicated and A Thomas Allen, Steven Aspland B Don Beer, professional bunch of Central Asian travel Leon Boelens, Pierre Brouillet, Joe Bryant enthusiasts. Thanks to the much-missed C James Chance, Arthur Clement De Givry, Suzannah Shwer for getting this title up and Judy Comont D Matthew Dearden, Kieran running one more time. -

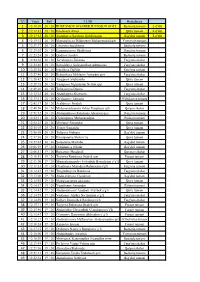

T/R 1 1-O'rin 2 2-O'rin 3 3-O'rin 4 5 6 7

T/r Vaqti Ball F.I.SH Hududingiz 1 12:10:05 20 / 20 RUSTAMOV OG'ABEK ILYOSJON OG'LI Beshariq tumani 1-o'rin 2 12:12:43 20 / 20 Ibrohimov Axror Quva tumani 2-o'rin 3 12:17:33 20 / 20 Xoshimova Sarvinoz Qobiljon qizi Bag'dod tumani 3-o'rin 4 12:19:12 20 / 20 Mamataliyeva Dildoraxon Muhammadali qizi Yozyovon tumani 5 12:21:17 20 / 20 Umarova Sug'diyona Beshariq tumani 6 12:23:02 20 / 20 Egamnazarova Shahloxon Dang'ara tumani 7 12:23:24 20 / 20 Qodirov Javohir Beshariq tumani 8 12:24:38 20 / 20 Jo'raboyeva Zebiniso Farg'ona shahar 9 12:24:46 20 / 20 Sotvoldieva Guloyim Rustambekovna Farg'ona shahar 10 12:25:54 20 / 20 Ismoilova Gullola Farg'ona tumani 11 12:27:46 20 / 20 Bektosheva Mohlaroy Anvarjon qizi Farg'ona shahar 12 12:28:42 20 / 20 Turģunov Shukurullo Quva tumani 13 12:29:18 20 / 20 Yusupova Niginabonu Ne'mat qizi Quva tumani 14 12:29:20 20 / 20 Tohirjonova Diyora Farg'ona shahar 15 12:32:35 20 / 20 Abdullayeva Shaxnoza Farg'ona shahar 16 12:33:31 20 / 20 Qo'chqorov Jahongir O'zbekiston tumani 17 12:43:17 20 / 20 Arabboyev Jòrabek Quva tumani 18 12:48:56 20 / 20 Muhammadjonova Odina Yoqubjon qizi Qo'qon shahar 19 12:51:32 20 / 20 Abdumalikova Ruhshona Abrorjon qizi Dang'ara tumani 20 12:52:11 20 / 20 G'ulomjonov Muhammadjon Rishton tumani 21 12:52:25 20 / 20 Mirzayev Samandar Quva tumani 22 12:55:03 20 / 20 Toirov Samandar Quva tumani 23 12:56:05 20 / 20 Tolipova Gulmira Bag'dod tumani 24 12:57:36 20 / 20 Ikromjonova Shohroʻza Quva tumani 25 12:57:45 20 / 20 Solijonova Marxabo Bag'dod tumani 26 12:06:19 19 / 20 Ochildinova Nilufar -

From the History of Ancient Cities of the Fergana Valley (In the Example of Mingtepa-Ershi)

European Scholar Journal (ESJ) Available Online at: https://www.scholarzest.com Vol. 2 No. 5, MAY 2021, ISSN: 2660-5562 FROM THE HISTORY OF ANCIENT CITIES OF THE FERGANA VALLEY (IN THE EXAMPLE OF MINGTEPA-ERSHI) Hakimov Abdumuxtor Abduxalimovich Senior Lecturer, Department of History of Uzbekistan, Andijan State University, Doctor of Philosophy in History (PhD) Article history: Abstract: Received: 2th April 2021 This article analyzes the study of data on the cultural history of Mingtepa-Ershi, Accepted: 20th April 2021 an ancient major stage of urbanization in the Fergana Valley, by archaeologists. Published: 9th May 2021 The article also states that the ruins of Mingtepa-Ershi are located on the Great Silk Road and was one of the largest cities in the history of 2,500 years, which made a worthy contribution to the development of world civilization. Keywords: Mingtepa-Ershi, Central Asian civilization, Fergana valley, Pamir-Fergana expedition, Chust culture, Buddha, Afrosiab, Jarqo'ton, Akhsikat, Munchoktepa, Dalvarzintepa, Academy of Material Culture, urbanization In the historiography of the twentieth century, the main factors and stages of development of the process of emergence and formation of cities in the Fergana Valley have not been sufficiently studied. The main reasons for this process are that in many Soviet archeological works (mainly in the works of "central" scholars and some local researchers) the Fergana Valley is described as a periphery, bordering on Central Asian civilizations, and the history of Fergana cities is largely denied. In fact, another scientist from the “center,” Yu.A. Zadneprovsky (Leningrad) promoted the idea that urbanization in the valley began in the late Bronze-Early Iron Age (early I millennium BC) in the 70s of last century and always defended this idea. -

Time, Place and People 1. Joseph Fletcher

Notes 1 World History and Central Asia - Time, Place and People 1. Joseph Fletcher, 'A Bibliography ofthe Publications ofJoseph Fletcher', Haruardfoumal oj Asiatic Studies, Vol. 46, no. 2,June 1986, pp . 7-10. 2. Robert Delort, Le Commerce desFourrures en Occident aLa fin du Moyen Age, 2 Vols., Ecole Francaise de Rome, Rome, 1978. 3. Sylvain Bensidoun, Samarcandeet La valliedu Zerafshan, Anthropos, Paris, 1979. 4. Arminius Vambery, Sketches oj Central Asia, Allen, London, 1868. 5. Eden Naby, 'The Uzbeks in Afghanistan', Central Asian Survey, Vol. 3, no. 1, 1984, pp. 1-21. 6. Martha Brill Olcott, The Kazakhs, Hoover, Stanford, California, 1987. 7. Joseph Fletcher, 'Ch'ing Inner Asia c.1800', in John K. Fairbank (ed.), The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 10, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1978, pp. 33-106, especially pp. 62-9. 8. L. N. Gumilev, Searches Jor an Imaginary Kingdom: The Legend oj the Kingdom oj PresterJohn, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1987. 9. Sechin Jagchid, Paul Hyer, Mongolia's Culture and Society, Westview, Boulder, Colorado, 1979; Elizabeth E. Bacon, Central Asians under Russian Rule, Cornell, Ithaca, New York, 1966. 10. John Masson Smith, 'Mongol and Nomadic Taxation', Haroard joumal oj Asiatic Studies, Vol. 30, 1970, pp. 46-85. II. Joseph Fletcher, 'Blood Tanistry: Authority and Succession in the Ottoman, Indian Muslim and later Chinese Empires', The Conference for the Theory ofDemocracy and Popular Participation, Bellagio , 1978. 12. Ludwig W. Adamec (ed .) , Historical and Political Gazetteer ojAJghanistan, Vol. 3, Herat and Northwestern AJghanistan, Akademische Druck-u Verlagsanstalt, Graz, 1975. 13. Firdausi, Thelipicofthe Kings, Shah-Nama, Reuben Levy (trns.), Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1965. -

UZB-KYR Along the Silk Road to Kashgar

The fascinating trip along two Asian Republics – Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, and also along Chinese Xinjiang to Kashgar is waiting for you. The ancient cities of the East: Samarkand, Bukhara, Osh, and also picturesque Fergana Valley, high mountainous Alay Valley, hot deserts and eternally snowed Pamir summits will appear in their entire splendor in the face of you. You will travel along that real ancient road, where numerous caravans ran along the Great Silk several ages ago. Also you will visit exotic Sunday Bazaar in Kashgar, from where you will undoubtedly take a lot of unforgettable impressions. The itinerary: Tashkent – Samarkand – Sarmysh – Nurata – “Aydar” Yurt Camp – Aydarkul lake – Bukhara – Tashkent – Kokand – Margilan – Fergana – Osh – Kashgar – Naryn – Issyk-Kul lake – Bishkek – Tashkent Duration: 15 days Number of tourists in group: minimum - 4, maximum - 16 Language: English / Russian PROGRAM OF THE TOUR Day 1 Arrival in Tashkent. Rest. Day 2 Transfer to Samarkand (300 km, ~ 5 hrs). Excursion: Registan square - the "heart" of Samarkand - ensemble of 3 majestic madrassahs (XIV-XVI c.c.) – Sherdor, Ulugbek and Tillya Qory, Bibi-Khanum the gigantic cathedral Mosque (XV c.), Gur-Emir Mausoleum of Timur (Tamerlan), his sons and grandson Ulugbek (XV c.), Tamerlan’s grandson Ulugbek’s the well-known ruler and astronomer-scientist observatory (1420 y.) - the remains of an immense (30 m. tall) astrolabe for observing stars position, Shakhi-Zinda – “The Living King” (XI-XVIII c.c.) Necropolis ofSamarkand rulers and noblemen, consisting of set of superb decorated mausoleums, exotic Siab bazaar. Day 3 Transfer to Aydar yurt camp in Kyzyl-Kum Desert (300 km, ~ 6 hrs). -

Linguistic Composition and Characteristics of Chinese Given Names DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8

Onoma 51 Journal of the International Council of Onomastic Sciences ISSN: 0078-463X; e-ISSN: 1783-1644 Journal homepage: https://onomajournal.org/ Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 Irena Kałużyńska Sinology Department Faculty of Oriental Studies University of Warsaw e-mail: [email protected] To cite this article: Kałużyńska, Irena. 2016. Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names. Onoma 51, 161–186. DOI: 10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.34158/ONOMA.51/2016/8 © Onoma and the author. Linguistic composition and characteristics of Chinese given names Abstract: The aim of this paper is to discuss various linguistic and cultural aspect of personal naming in China. In Chinese civilization, personal names, especially given names, were considered crucial for a person’s fate and achievements. The more important the position of a person, the more various categories of names the person received. Chinese naming practices do not restrict the inventory of possible given names, i.e. given names are formed individually, mainly as a result of a process of onymisation, and given names are predominantly semantically transparent. Therefore, given names seem to be well suited for a study of stereotyped cultural expectations present in Chinese society. The paper deals with numerous subdivisions within the superordinate category of personal name, as the subclasses of surname and given name. It presents various subcategories of names that have been used throughout Chinese history, their linguistic characteristics, their period of origin, and their cultural or social functions. -

Checklist of Rust Fungi from Ketmen Ridge (Southeast of Kazakhstan)

Plant Pathology & Quarantine 7(2): 110–135 (2017) ISSN 2229-2217 www.ppqjournal.org Article Doi 10.5943/ppq/7/2/4 Copyright © Mushroom Research Foundation Checklist of rust fungi from Ketmen ridge (southeast of Kazakhstan) Rakhimova YV, Yermekova BD, Kyzmetova LA Institute of Botany and Phytointroduction, Timiryasev Str. 36D, Almaty, 050040, Kazakhstan Rakhimova YV, Yermekova BD, Kyzmetova LA 2017 – Checklist of rust fungi from Ketmen ridge (southeast of Kazakhstan). Plant Pathology & Quarantine 7(2), 110–135, Doi 10.5943/ppq/7/2/4 Abstract The Ketmen ridge has 84 species belonging to class Urediniomycetes. The class is represented by 11 genera from 6 families. The largest genera are Puccinia (48 species) and Uromyces (12 species). The following species are widely distributed in the territory: Gymnosporangium fusisporum on Cotoneaster spp., Puccinia chrysanthemi on Artemisia spp. and Puccinia menthae on Mentha spp. Rust fungi attack 134 species of host plants. Key words – aecia – host plants – mycobiota – telia – uredinia Introduction Ketmen ridge (Ketpen, Uzynkara) is located to the east of the Zailiysky Alatau (Trans-Ili Alatau) and separated from the Central Tien-Shan by the Kegen depression. This, the most eastern ridge from the northern chains of the Tien Shan, extends in an east-west direction. The Ketmen ridge is more than 300 km long, 40–50 km wide and 3500–4200 m high. The western part of the ridge (about 160 km long) is located in Kazakhstan territory, and the eastern part in China. The highest point of the ridge, in the eastern part of the state border of Kazakhstan, is Nebesnaya peak (3638 m). -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis.