Regulatory Reform in the Telecommunications Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 BCE Annual Information Form

Annual Information Form BCE Inc. For the year ended December 31, 2011 March 8, 2012 In this Annual Information Form, Bell Canada is, unless otherwise indicated, referred to as Bell, and comprises our Bell Wireline, Bell Wireless and Bell Media segments. Bell Aliant means, collectively, Bell Aliant Inc. and its subsidiaries. All dollar figures are in Canadian dollars, unless stated otherwise. The information in this Annual Information Form is as of March 8, 2012, unless stated otherwise, and except for information in documents incorporated by reference that have a different date. TABLE OF CONTENTS PARTS OF MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION & ANALYSIS AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ANNUAL INCORPORATED BY REFERENCE INFORMATION (REFERENCE TO PAGES OF THE BCE INC. FORM 2011 ANNUAL REPORT) Caution Regarding Forward-Looking Statements 2 32-34; 54-69 Corporate Structure 4 Incorporation and Registered Offices 4 Subsidiaries 4 Description of Our Business 5 General Summary 5 23-28; 32-36; 41-47 Strategic Imperatives 6 29-31 Our Competitive Strengths 6 Marketing and Distribution Channels 8 Our Networks 9 32-34; 54-69 Our Employees 12 Corporate Responsibility 13 Competitive Environment 15 54-57 Regulatory Environment 15 58-61 Intangible Properties 15 General Development of Our Business 17 Three-Year History (1) 17 Our Capital Structure 20 BCE Inc. Securities 20 112-114 Bell Canada Debt Securities 21 Ratings for BCE Inc. and Bell Canada Securities 21 Ratings for Bell Canada Debt Securities 22 Ratings for BCE Inc. Preferred Shares 22 Outlook 22 General Explanation 22 Explanation of Rating Categories Received for our Securities 24 Market for our Securities 24 Trading of our Securities 25 Our Dividend Policy 27 Our Directors and Executive Officers 28 Directors 28 Executive Officers 30 Directors’ and Executive Officers’ Share Ownership 30 Legal Proceedings 31 Lawsuits Instituted by BCE Inc. -

International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking

telecoms.qxd 9/03/99 10:06 AM Page 1 International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications International Services Benchmarking March 1999 Commonwealth of Australia 1999 ISBN 0 646 33589 8 This work is subject to copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, the work may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of an acknowledgment of the source. Reproduction for commercial use or sale requires prior written permission from AusInfo. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Manager, Legislative Services, AusInfo, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601. Inquiries: Media and Publications Productivity Commission Locked Bag 2 Collins Street East Post Office Melbourne Vic 8003 Tel: (03) 9653 2244 Fax: (03) 9653 2303 Email: [email protected] An appropriate citation for this paper is: Productivity Commission 1999, International Benchmarking of Australian Telecommunications Services, Research Report, AusInfo, Melbourne, March. The Productivity Commission The Productivity Commission, an independent Commonwealth agency, is the Government’s principal review and advisory body on microeconomic policy and regulation. It conducts public inquiries and research into a broad range of economic and social issues affecting the welfare of Australians. The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the community as a whole. Information on the Productivity Commission, its publications and its current work program can be found on the World Wide Web at www.pc.gov.au or by contacting Media and Publications on (03) 9653 2244. -

APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership

EB-2015-0141 Ontario Energy Board IN THE MATTER OF the Ontario Energy Board Act, 1998, S.O. 1998, c.15, (Schedule B); AND IN THE MATTER OF Decision EB-2013-0416/EB- 2014-0247 of the Ontario Energy Board (the “OEB”) issued March 12, 2015 approving distribution rates and charges for Hydro One Networks Inc. (“Hydro One”) for 2015 through 2017, including an increase to the Pole Access Charge; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision of the OEB issued April 17, 2015 setting the Pole Access Charge as interim rather than final; AND IN THE MATTER OF the Decision and Order issued June 30, 2015 by the OEB granting party status to Rogers Communications Partnership, Allstream Inc., Shaw Communications Inc., Cogeco Cable Inc., on behalf of itself and its affiliate, Cogeco Cable Canada LP, Quebecor Media, Bragg Communications, Packet-tel Corp., Niagara Regional Broadband Network, Tbaytel, Independent Telecommunications Providers Association (ITPA) and Canadian Cable Systems Alliance Inc. (CCSA) (collectively, the “Carriers”); AND IN THE MATTER OF Procedural Order No. 4 of the OEB issued October 26, 2015 setting dates for, inter alia, evidence of the Carriers. APPENDICES to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 EB-2015-0141 APPENDIX A to the Evidence of Michael Piaskoski Rogers Communications Partnership November 20, 2015 Michael E. Piaskoski SUMMARY OF QUALIFICATIONS Eight years in Rogers Regulatory proceeded by 12 years as a telecom lawyer specializing in regulatory, competition and commercial matters. Bright, professional and ambitious performer who continually exceeds expectations. Expertise in drafting cogent, concise and easy-to-understand regulatory and legal filings and litigation materials. -

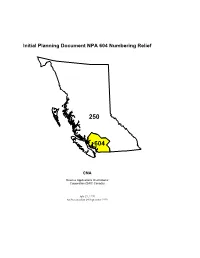

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief

Initial Planning Document NPA 604 Numbering Relief 250 604 CNA Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC Canada) July 27, 1999 As Presented on 24 September 1999 INITIAL PLANNING DOCUMENT NPA 604 NUMBERING RELIEF JULY 27, 1999 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................... 1 3. CENTRAL OFFICE CODE EXHAUST .................................................................................................... 2 4. CODE RELIEF METHODS...................................................................................................................... 3 4.1. Geographic Split.............................................................................................................................. 3 4.1.1. Definition ...................................................................................................................................... 3 4.1.2. General Attributes ........................................................................................................................ 4 4.2. Distributed Overlay .......................................................................................................................... 4 4.2.1. Definition ..................................................................................................................................... -

PART a Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100

iTeraTEL Communications CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Title Page ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF This Tariff sets out the rates, terms and conditions applicable to the interconnection arrangements provisioned to providers of telecommunications services and facilities. Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 1 Explanation of Symbols The following symbols are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: A Increase in rate or charge C Change in wording D Discontinued rate or regulation F Reformatting of existing material with no change to rate or charge M Matter moved from its previous location N New wording, rate or charge R Reduction in rate or charge S Reissued matter Abbreviations of Companies Names The following companies names are used in this Tariff and have meanings as shown: Aliant Aliant Telecom Inc. Bell Bell Canada Bell Aliant Bell Aliant Regional Communications, Limited Partnership IslandTel Island Telecom Inc. MTS MTS Allstream Inc. MTT Maritime Tel & Tel Limited NBTel NBTel NewTel NewTel Communications NorthernTel NorthernTel, Limited Partnership SaskTel SaskTel TBayTel TBayTel TCBC TELUS Communications Company, operating in British Columbia TCC TELUS Communications Company TCI TELUS Communications Company, operating in Alberta TCQ TELUS Communications Company, operating in Quebec Télébec Télébec, société en commandite Issue Date: December 2,2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2015 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 2 Check Page Issue Date: December 2, 2019 Effective Date: January 15, 2020 Tariff Notice 1 iTeraTEL Communications Inc. CRTC 15190 ACCESS SERVICES TARIFF Original Page 3 Table of Contents Page Explanation of Symbols 1 Abbreviations of Companies Names 1 Check Page 2 Table of Contents 3 PART A Definitions and General Terms 5 ITEM 100. -

49807 Bell AIF Eng Clean

BELL CANADA ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2001 APRIL 15, 2002 2001 T ABLE OF CONTENTS Annual Information Form for the year ended December 31, 2001 April 15, 2002 Documents Incorporated by Reference . .1 Documents incorporated by reference Part of Annual Information Form in Trade-marks . .1 Document which incorporated by reference Item 1 • Corporate Structure of Bell Canada . .2 Portions of the 2001 Bell Canada Financial Information Item 5 Item 2 • General Development of Bell Canada . .2 Item 3 • Business of Bell Canada . .3 General . .3 Principal Service Area . .5 Subsidiaries and Associated Companies . .5 Regulation . .8 Competition . .12 Capital Expenditures . .15 Environment . .15 Employee Relations . .16 Legal Proceedings . .16 Trade-marks Certain Contracts . .17 Owner Trade-mark Forward-Looking Statements . .18 Bell Canada Rings & Head Design Risk Factors . .18 (Bell Canada corporate logo) Bell Item 4 • Selected Financial Information (Consolidated) . .20 Bell World Item 5 • Management’s Discussion and Analysis . .21 Espace Bell Sympatico Item 6 • Market for the Securities of Bell Canada . .21 Bell ActiMedia Inc. Yellow Pages Item 7 • Directors and Officers of Bell Canada . .21 Bell Mobility Inc. / Bell Mobilité inc. Mobile Browser Item 8 • Additional Information . .23 Manitoba Telecom Services Inc. First Rate Schedule – Directors’ and Officers’ Remuneration . .24 Stentor Resource Centre Inc. / Datapac Centre de ressources Stentor Inc. Megalink SmartTouch AT&T Corp. AT&T MCI Communications Corporation Hyperstream OnStar Corporation Onstar NOTES: (1) Unless the context indicates otherwise, “Bell Canada” refers to Bell Canada and its subsidiaries Yahoo! Inc. Yahoo! and associated companies. (2) All dollar figures are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise indicated. -

A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment Of

TELECOMMUNICATIONS AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT by Donald Ross McDonald B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1969 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in an Interdisciplinary Program in Urban Studies We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Jan. ^9%~ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of UffB^ STODlE^ The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date . itf , (Q7^ i ABSTRACT This thesis is broadly concerned with the relationship of com• munications to urban development. It specifically develops a communications perspective on spatial structure in the Vancouver, B.C., metropolitan area by examination of one communication variable, telephone traffic. Origin-destination calling data are used to identify communication networks, suggest functional associations, and relate social area structure to communicative (interactive) behaviour. A further purpose is to employ the above findings in developing suggestions as to possible imports of future communication technologies. For the first three chapters, the mode, i.e. telephone hardware, is held constant, in the fourth chapter the hardware is considered as a variable. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply indebted to Dr. -

Rogers Wireless Inc

333 Bloor Street East Toronto, Ontario M4W 1G9 Tel. (416) 935-7211 Fax (416) 935-7719 [email protected] Dawn Hunt Vice-President Government & Intercarrier Relations March 14, 2003 Jan Skora Director General Radiocommunications and Broadcasting Regulatory Branch EMAILED TO: [email protected] Industry Canada 300 Slater Street Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C8 Dear Mr. Skora, Re: Comments - Canada Gazette Notices: DGRB-004-02 and DGRB-001-03 Consultation on a New Fee and Licensing Regime for Cellular and Incumbent Personal Communications Services (PCS) Licensees Pursuant to the Canada Gazette, Part I, dated December 21, 2002, and February 21, 2003 respectively, RWI is pleased to file the attached comments regarding the above noted proceeding. The comments are submitted in Adobe Acrobat (PDF) version 5.0 software produced on a computer using a Windows 2000 Professional operating system. If there are any questions regarding these comments, please do not hesitate to contact the undersigned. Sincerely, Original Signed by: Joel Thorp On Behalf of: Dawn Hunt, DH:jt Attach. Department of Industry CONSULTATION ON A NEW FEE AND LICENSING REGIME FOR CELLULAR AND INCUMBENT PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS SERVICES (PCS) LICENSEES DGRB-004-02 COMMENTS OF ROGERS WIRELESS INC. March 14, 2003 COMMENTS OF ROGERS WIRELESS INC. DGRB-004-02 Table of Contents 1EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................3 DETAILED COMMENTS...................................................................................................4 -

Visions of Electric Media Electric of Visions

TELEVISUAL CULTURE Roberts Visions of Electric Media Ivy Roberts Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Visions of Electric Media Televisual Culture Televisual culture encompasses and crosses all aspects of television – past, current and future – from its experiential dimensions to its aesthetic strategies, from its technological developments to its crossmedial extensions. The ‘televisual’ names a condition of transformation that is altering the coordinates through which we understand, theorize, intervene, and challenge contemporary media culture. Shifts in production practices, consumption circuits, technologies of distribution and access, and the aesthetic qualities of televisual texts foreground the dynamic place of television in the contemporary media landscape. They demand that we revisit concepts such as liveness, media event, audiences and broadcasting, but also that we theorize new concepts to meet the rapidly changing conditions of the televisual. The series aims at seriously analyzing both the contemporary specificity of the televisual and the challenges uncovered by new developments in technology and theory in an age in which digitization and convergence are redrawing the boundaries of media. Series editors Sudeep Dasgupta, Joke Hermes, Misha Kavka, Jaap Kooijman, Markus Stauff Visions of Electric Media Television in the Victorian and Machine Ages Ivy Roberts Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: ‘Professor Goaheadison’s Latest,’ Fun, 3 July 1889, 6. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden -

Deterministic Communications for Protection Applications Over Packet-Based Wide-Area Networks

Deterministic Communications for Protection Applications Over Packet-Based Wide-Area Networks Kenneth Fodero, Christopher Huntley, and Paul Robertson Schweitzer Engineering Laboratories, Inc. © 2018 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. Permission from IEEE must be obtained for all other uses, in any current or future media, including reprinting/republishing this material for advertising or promotional purposes, creating new collective works, for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or reuse of any copyrighted component of this work in other works. This paper was presented at the 71st Annual Conference for Protective Relay Engineers and can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1109/CPRE.2018.8349789. For the complete history of this paper, refer to the next page. Presented at RVP-AI 2018 Acapulco, Mexico July 15–20, 2018 Previously presented at the 71st Annual Conference for Protective Relay Engineers, March 2018, IEEE ROC&C 2017, November 2017, and 44th Annual Western Protective Relay Conference, October 2017 Previous revised edition released March 2018 Originally presented at the 4th Annual PAC World Americas Conference, August 2017 1 Deterministic Communications for Protection Applications Over Packet-Based Wide-Area Networks Kenneth Fodero, Christopher Huntley, and Paul Robertson, Schweitzer Engineering Laboratories, Inc. Abstract—There is a growing trend in the power utility Time-division multiplexing (TDM) has been widely adopted industry to move away from traditional synchronous optical across the power utility industry as the preferred WAN network/synchronous digital hierarchy (SONET/SDH) systems transport technology because it provides low-latency, for wide-area network (WAN) communications. Information technology (IT) teams and equipment manufacturers are deterministic, and minimal-asymmetry performance. -

Paging Companies IXO/TAP Modem Numbers ([email protected])

Head Office Suite 135 4474 Blakie Road London, ON, Canada N6L 1G7 Phone : +1.519.652.0401 Paging Companies IXO/TAP Modem Numbers ([email protected]) This document contains the known IXO/TAP dial-up phone numbers that can be used with First PAGE. Please send any questions, problems or additions to: [email protected] Provider Coverage Phone Number Speed Modem Settings Alpha Length A Better Beep Bakersfield, CA 805-334-7002 A Better Beep Fresno, CA 209-778-9451 A Better Beep San Luis Obispo, CA 805-542-4050 A Better Beep Santa Barbara, CA 805-730-3118 A Better Beep Santa Rosa, CA 707-523-6571 A Better Beep Stockton, CA 209-762-3094 Action Page 800-933-4585 7,e,1 (1200 baud) Advanced Paging US New Orleans, LA 888-723-2337 Advantage 805-647-5962 AirPage Austria 43 688 3322111 7,e,1 Air Touch 800-310-2193 Air Touch 800-326-0038 Air Touch 312-514-9243 2400,7,e,1 Air Touch 800-326-0038 Air Touch 800-310-2193 Air Touch Albuquerque, NM 505-883-1977 Air Touch Athens, GA 706-369-8134 Air Touch Atlanta, GA 404-873-6337 Air Touch Austin, TX 512-873-8719 Air Touch Austin/San Antonio, TX 210-349-2159 Air Touch Bakersfield, CA 805-324-5934 Air Touch Boca Raton, FL 407-994-3507 800-870-9537 Air Touch Boise, ID 208-869-0004 Air Touch Brandenton, FL 813-751-3658 Air Touch CA 888-287-7108 Air Touch Casa Grande, AZ 520-426-1220 800-624-7868 Air Touch Chicago, IL 708-708-4027 Air Touch Chula Vista, CA 619-296-0771 Air Touch Cincinnati, OH 513-665-9917 Air Touch Cleveland, OH 216-241-3825 Air Touch Dallas/Fort Worth, TX 800-672-4371 817-265-1848 Air Touch Daytona, FL 904-252-4184 Air Touch Denver, CO 303-368-4727 Air Touch Detroit, MI 800-371-8800 800-564-7079 810-539-9667 Air Touch Escondido, CA 619-747-5007 Air Touch Flagstaff, AZ 520-744-7317 Air Touch Fort Myers, FL 813-275-8934 Air Touch Fresno, CA 209-222-9811 Air Touch Ft. -

Spectrum Maanagement in Australia

SPECTRUM MANAGEMENT FOR A CONVERGING WORLD: CASE STUDY ON AUSTRALIA International Telecommunication Union Spectrum Management for a Converging World: Case Study on Australia This case study has been prepared by Fabio Leite <[email protected]>, Counsellor, Radiocommunication Bureau, ITU as part of a Workshop on Radio Spectrum Management for a Converging World jointly produced under the New Initiatives programme of the Office of the Secretary General and the Radiocommunication Bureau. The workshop manager is Eric Lie <[email protected]>, and the series is organized under the overall responsibility of Tim Kelly <[email protected]>, Head, ITU Strategy and Policy Unit (SPU). Other case studies on spectrum management in the United Kingdom and Guatemala can be found at: http://www.itu.int/osg/sec/spu/ni/fmi/case_studies/. This report has benefited from the input and comments of many people to whom the author owes his sincere thanks. In particular, I would like to thank Colin Langtry, my Australian colleague in the Radiocommunication Bureau, for his invaluable comments and explanations, as well as for his placid tolerance of my modestly evolving knowledge of his country. I would also like to express my gratitude to all officials and representatives whom I visited in Australia and who assisted me in preparing this case study, particularly to those of the Australian Communications Authority for their availability in providing support, explanations, comments, and documentation, which made up this report. Above all, I am grateful to those who were kind enough to accept this report as a succinct but fair description of the spectrum management framework in Australia.