Bob Carlin Capped Crusader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music K-8 Marketplace 2021 Spring Update Catalog

A Brand New Resource For Your Music Classroom! GAMES & GROOVES FOR BUCKET BAND, RHYTHM STICKS, AND LOTS OF JOYOUS INSTRUMENTS by John Riggio and Paul Jennings Over the last few years, bucket bands have grown greatly in popularity. Percussion is an ideal way to teach rhythmic concepts and this low-cost percussion ensemble is a great way to feel the joy of group performance without breaking your budget. This unique new product by John Riggio and Paul Jennings is designed for players just beyond beginners, though some or all players can easily adapt the included parts. Unlike some bucket band music, this is written with just one bucket part, intended to be performed on a small to medium-size bucket. If your ensemble has large/bass buckets, they can either play the written part or devise a more bass-like part to add. Every selection features rhythm sticks, though the tracks are designed to work with just buckets, or any combination of the parts provided. These change from tune to tune and include Boomwhackers®, ukulele, cowbell, shaker, guiro, and more. There are two basic types of tunes here, games and game-like tunes, and grooves. The games each stand on their own, and the grooves are short, repetitive, and fun to play, with many repeats. Some songs have multiple tempos to ease learning. And, as you may have learned with other music from Plank Road Publishing and MUSIC K-8, we encourage and permit you to adapt all music to best serve your needs. This unique collection includes: • Grizzly Bear Groove • Buckets Are Forever (A Secret Agent Groove) • Grape Jelly Groove • Divide & Echo • Build-A-Beat • Rhythm Roundabout ...and more! These tracks were produced by John Riggio, who brings you many of Plank Road’s most popular works. -

Kraut Creek Ramblers

Appalachian State University’s Office of Arts and Cultural Programs presents 2019-2020 Season K-12 Performing Arts Series October 23, 2019 Kraut Creek Ramblers School Bus As an integral part of the Performing Arts Series, APPlause! matinées offer a variety of performances at venues across the Appalachian State University campus that feature university-based artists as well as local, regional and world-renowned professional artists. These affordable performances offer access to a wide variety of art disciplines for K-12 students. The series also offers the opportunity for students from the Reich College of Education to view a field trip in action without having to leave campus. Among the 2019-2020 series performers, you will find those who will also be featured in the Performing Arts Series along with professional artists chosen specifically for our student audience as well as performances by campus groups. Before the performance... Familiarize your students with what it means to be a great audience member by introducing these theatre etiquette basics: • Arrive early enough to find your seats and settle in before the show begins (20- 30 minutes). • Remember to turn your electronic devices OFF so they do not disturb the performers or other audience members. • Remember to sit appropriately and to stay quiet so that the audience members around you can enjoy the show too. PLEASE NOTE: *THIS EVENT IS SCHEDULED TO LAST APPROX 60 MINUTES. 10:00am – 11:00am • Audience members arriving by car should plan to park in the Rivers Street Parking Deck. There is a small charge for parking. Buses should plan to park along Rivers Street – Please indicate to the Parking and Traffic Officer when you plan to move your bus (i.e. -

American Old-Time Musics, Heritage, Place A

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SOUNDS OF THE MODERN BACKWOODS: AMERICAN OLD-TIME MUSICS, HERITAGE, PLACE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY LAURA C.O. SHEARING CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2020 ã Copyright 2020 Laura C.O. Shearing All rights reserved. ––For Henrietta Adeline, my wildwood flower Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. vi Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... vii Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... ix Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 1. Contextualizing Old-Time ..................................................................................................... 22 2. The Making of an Old-Time Heritage Epicenter in Surry County, North Carolina ................... 66 3. Musical Trail-Making in Southern Appalachia ....................................................................... 119 4. American Old-Time in the British Isles ................................................................................ -

Happy Traum……….…………………….….Page 2 Sun, July 11, at Fishing Creek Salem UMC • a Legend Ireland Tour…

Happy Traum……….…………………….….Page 2 Sun, July 11, at Fishing Creek Salem UMC • A legend Ireland Tour….......….......…..........….4 of American roots music joins us for a guitar workshop Folk Festival Scenes…………..…....8-9 and concert, with a blues jam in between. Emerging Artist Showcase………....6 Looking Ahead……………….…….…...12 Andy’s Wild Amphibian Show….........……..Page 3 Member Recognition.….................15 Wed, Jul 14 • Tadpoles, a five-gallon pickle jar and silly parental questions are just a few elements of Andy Offutt Irwin’s zany live-streamed program for all ages. Resource List Liars Contest……………....……….………...Page 3 Subscribe to eNews Wed, Jul 14 • Eight tellers of tall tales vie for this year’s Sponsor an Event Liars Contest title in a live-streamed competition emceed by storyteller extraordinaire Andy Offutt Irwin. “Bringing It Home”……….……...……........Page 5 Executive Director Jess Hayden Wed, Aug 11 • Three local practitioners of traditional folk 378 Old York Road art — Narda LeCadre, Julie Smith and Rachita Nambiar — New Cumberland, PA 17070 explore “Beautiful Gestures: Making Meaning by Hand” in [email protected] a virtual conversation with folklorist Amy Skillman. (717) 319-8409 Solo Jazz Dance Class……........................…Page 6 More information at Fri, Aug 13, Mt. Gretna Hall of Philosophy Building • www.sfmsfolk.org Let world-champion swing dancer Carla Crowen help get you in the mood to boogie to the music of Tuba Skinny. Tuba Skinny………………........................…Page 7 Fri, Aug 13, at Mt. Gretna Playhouse • This electrifying ensemble has captivated audiences around the world with its vibrant early jazz and traditional New Orleans sound. Nora Brown……………... Page 10 Sat, Aug 14, at Mt. -

Primary Music Previously Played

THE AUSTRALIAN SCHOOL BAND & ORCHESTRA FESTIVAL MUSIC PREVIOUSLY PLAYED HELD ANNUALLY THROUGH JULY, AUGUST & SEPTEMBER A non-competitive, inspirational and educational event Primary School Concert and Big Bands WARNING: Music Directors are advised that this is a guide only. You should consult the Festival conditions of entry for more specific information as to the level of music required in each event. These information on these lists was entered by participating bands and may contain errors. Some of the music listed here may be regarded as too easy or too difficult for the section in which it is listed. Playing music which is not suitable for the section you have entered may result in you being awarded a lower rating or potentially ineligible for an award. For any further advice, please feel free to contact the General Manager of the Festival at [email protected], visit our website at www.asbof.org.au or contact one of the ASBOF Advisory Panel Members. www.asbof.org.au www.asbof.org.au I [email protected] I PO Box 833 Kensington 1465 I M 0417 664 472 Lithgow Music Previously Played Title Composer Arranger Aust A L'Eglise Gabriel Pierne Kenneth Henderson A Night On Bald Mountain Modest Moussorgsky John Higgins Above the World Rob GRICE Abracadabra Frank Tichelli Accolade William Himes William Himes Aerostar Eric Osterling Air for Band Frank Erickson Ancient Dialogue Patrick J. Burns Ancient Voices Michael Sweeney Ancient Voices Angelic Celebrations Randall D. Standridge Astron (A New Horizon) David Shaffer Aussie Hoedown Ralph Hultgren -

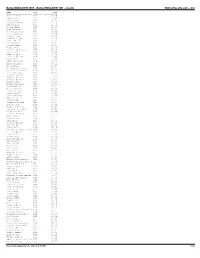

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D. -

{PDF EPUB} Blood in West Virginia Brumfield V. Mccoy by Brandon Kirk William Greenville “Green” Mccoy

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Blood in West Virginia Brumfield v. McCoy by Brandon Kirk William Greenville “Green” McCoy. Are you adding a grave photo that will fulfill this request? Yes, fulfill request No, this is not a grave photo. Oops, something didn't work. Close this window, and upload the photo(s) again. Make sure that the file is a photo. Photos larger than 8Mb will be reduced. Photos larger than 8.0 MB will be optimized and reduced. Each contributor can upload a maximum of 5 photos for a memorial. A memorial can have a maximum of 20 photos from all contributors. The sponsor of a memorial may add an additional 10 photos (for a total of 30 on the memorial). Include gps location with grave photos where possible. No animated GIFs, photos with additional graphics (borders, embellishments.) No post-mortem photos. File Name · Request Grave Photo. Photo request failed. Try again later. The note field is required. Leave a Flower. Your Scrapbook is currently empty. Add to your scrapbook. You are only allowed to leave one flower per day for any given memorial. View Flower. Share. Facebook Twitter Pinterest Email. Save To. Ancestry Virtual Cemetery Copy to clipboard Print. Your Virtual Cemeteries. Select to include on a virtual cemetery: Loading… Report Abuse. Are you sure that you want to report this flower to administrators as offensive or abusive? This flower has been reported and will not be visible while under review. Failed to report flower. Try again later. Remove Flower. Failed to remove flower. Try again later. Delete Memorial. -

Haley, James Edward (Ed) and Family 94-085 Collection

HALEY, JAMES EDWARD (ED) AND FAMILY 94-085 COLLECTION Physical description: .75 l.f. (copies) including 8 audio tapes ( TTA-187A/H) 1 volume (copy) 1 binder (copy) Dates: Ca. 1946-1947 Restriction: These materials may be used only with the permission of the donor. Provenance: These materials were loaned for copying by John Hartford of Madison Tennessee with the permission of the Haley family. Some of these discs were copied earlier by the Library of Congress and appear on the Rounder album Ed Haley, Parkersburg Landing (Rounder 1010) Biographical Sketch: James Edward (Ed) Haley was born on Hart’s Creek, Logan county, West Virginia, in 1885, the son of Andrew Jackson and Emma (Mullins) Haley. He lost his vision in early childhood and received no formal education. As an adult supported himself by his fiddle playing in West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio. In 1914 he married (Martha) Ella of Morehead Kentucky, who was also blind, and moved to Ashland Kentucky. The Haleys, who had five children, divorced in 1935 but continued to play together. Ed Haley died in 1951, Ella in 1954. Scope and Content: This collection consists of a photocopied volume of John Hartford’s research notes concerning the Haley family and regional history and 8 reel to reel analog audio tapes of instantaneous discs made by West Virginia fiddler J.E. (Ed) Haley of West Virginia and his family, ca. 1946-1947. The volume includes detailed information on the family, including copies of photographs; song texts, sometimes with explanatory notes including an extensive discussion of “Lincoln Country Crew,” a murder ballad; Hartford’s transcriptions of Haley’s tunes and information on those and other tunes in Haley’s repertoire; drawings of Haley’s fiddle positions based on information from his son Lawrence and other information on his playing technique; and scattered information on other fiddlers, especially “Uncle Jack” McElwain from whom Haley learned a number of tunes. -

Unlocking Our Potential California State University, Chico

California State University, Chico Unlocking Our Potential 2017–18 University Foundation Annual Report Charisse Armstrong Introduction Class Year: Freshman Hometown: Cedarville, California State University, Modoc County Chico’s 131 years of public Major: service began in 1887, when Computer Animation and Game Development John Bidwell donated eight Scholarship: acres of his prized cherry President’s Scholar orchard to build Chico Normal Career Aspirations: School—establishing the Work in an animation studio first institution of higher for small game developer or major education in the North State. corporation such as Disney/Pixar The University Foundation was created in 1940. The nonprofit auxiliary engages those Being a“ recipient of who care about Chico State; this scholarship has provides opportunities to helped me achieve enhance its teaching, research, my lifelong dream of and community programs; attending college— and guarantees ethical stewardship of gifts received. it really would not have been possible The return on an investment in otherwise. It’s been the University is far-reaching and never-ending. In addition amazing to put my to describing the Foundation’s heart and soul into fundraising and investment what I’m learning performance, this annual instead of working report highlights the human multiple jobs. It has impact of giving. It features opened so many stories of donors, students, possibilities. I could faculty, staff, and community members and demonstrates not be more grateful the essential role your for what it has philanthropy plays done for me. in our future. Your generosity helps us unlock student potential, open doors to creativity, and jumpstart innovation. Thank you. -

Jemf Quarterly

JEMF QUARTERLY JOHN EDWARDS MEMORIAL FOUNDATION VOL. XII SPRING 1976 No. 41 THE JEMF The John Edwards Memorial Foundation is an archive and research center located in the Folklore and Mythology Center of the University of California at Los Angeles. It is chartered as an educational non-profit corporation, supported by gifts and contributions. The purpose of the JEMF is to further the serious study and public recognition of those forms of American folk music disseminated by commercial media such as print, sound recordings, films, radio, and television. These forms include the music referred to as cowboy, western, country & western, old time, hillbilly, bluegrass, mountain, country ,cajun, sacred, gospel, race, blues, rhythm' and blues, soul, and folk rock. The Foundation works toward this goal by: gathering and cataloguing phonograph records, sheet music, song books, photographs, biographical and discographical information, and scholarly works, as well as related artifacts; compiling, publishing, and distributing bibliographical, biographical, discographical, and historical data; reprinting, with permission, pertinent articles originally appearing in books and journals; and reissuing historically significant out-of-print sound recordings. The Friends of the JEMF was organized as a voluntary non-profit association to enable persons to support the Foundation's work. Membership in the Friends is $8.50 (or more) per calendar year; this fee qualifies as a tax deduction. Gifts and contributions to the Foundation qualify as tax deductions. DIRECTORS ADVISORS Eugene W. Earle, President Archie Green, 1st Vice President Ry Cooder Fred Hoeptner, 2nd Vice President David Crisp Ken Griffis, Secretary Harlan Dani'el D. K. Wilgus, Treasurer David Evans John Hammond Wayland D. -

“Knowing Is Seeing”: the Digital Audio Workstation and the Visualization of Sound

“KNOWING IS SEEING”: THE DIGITAL AUDIO WORKSTATION AND THE VISUALIZATION OF SOUND IAN MACCHIUSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO September 2017 © Ian Macchiusi, 2017 ii Abstract The computer’s visual representation of sound has revolutionized the creation of music through the interface of the Digital Audio Workstation software (DAW). With the rise of DAW- based composition in popular music styles, many artists’ sole experience of musical creation is through the computer screen. I assert that the particular sonic visualizations of the DAW propagate certain assumptions about music, influencing aesthetics and adding new visually- based parameters to the creative process. I believe many of these new parameters are greatly indebted to the visual structures, interactional dictates and standardizations (such as the office metaphor depicted by operating systems such as Apple’s OS and Microsoft’s Windows) of the Graphical User Interface (GUI). Whether manipulating text, video or audio, a user’s interaction with the GUI is usually structured in the same manner—clicking on windows, icons and menus with a mouse-driven cursor. Focussing on the dialogs from the Reddit communities of Making hip-hop and EDM production, DAW user manuals, as well as interface design guidebooks, this dissertation will address the ways these visualizations and methods of working affect the workflow, composition style and musical conceptions of DAW-based producers. iii Dedication To Ba, Dadas and Mary, for all your love and support. iv Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................. -

September / October

CONCERT & DANCE LISTINGS • CD REVIEWS • FREE EVENTS FREE BI-MONTHLY Volume 5 Number 5 September-October 2005 THESOURCE FOR FOLK/TRADITIONAL MUSIC, DANCE, STORYTELLING & OTHER RELATED FOLK ARTS IN THE GREATER LOS ANGELES AREA “Don’t you know that Folk Music is illegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers THE TILT OF THE KILT Wicked Tinkers Photo by Chris Keeney BY RON YOUNG inside this issue: he wail of the bagpipes…the twirl of the dancers…the tilt of the kilts—the surge of the FADO: The Soul waves? Then it must be the Seaside Highland Games, which are held right along the coast at of Portugal T Seaside Park in Ventura. Highly regarded for its emphasis on traditional music and dance, this festival is only in its third year but is already one Interview: of the largest Scottish events in the state. Games chief John Lowry and his wife Nellie are the force Liz Carroll behind the rapid success of the Seaside games. Lowry says that the festival was created partly because there was an absence of Scottish events in the region and partly to fill the void that was created when another long-standing festival PLUS: was forced to move from the fall to the spring. With its spacious grounds and variety of activities, the LookAround Seaside festival provides a great opportunity for first-time Highland games visitors who want to experience it all. This How Can I Keep From Talking year’s games will be held on October 7, 8 and 9, with most of the activity taking place on the Saturday and Sunday.