Culture and Citizenship: a Case Study of Practice in the BBC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Passion of Christ on Television: Intertextuality As a Mode of Storytelling

religions Article The Passion of Christ on Television: Intertextuality as a Mode of Storytelling Stefan Gärtner Department of Practical Theology and Religious Studies, Tilburg University, P.O. Box 90153, NL-5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands; [email protected] Received: 2 October 2020; Accepted: 9 November 2020; Published: 13 November 2020 Abstract: The Passion is a contemporary performance of the passion of Christ live on stage, combined with pop music, city marketing, social media, and entertainment. The result is an encounter between the Christian gospel and traditional elements of devotion like a procession of the cross on the one hand, and the typical mediatization and commercialization of late modern society on the other. In this article, I will first briefly describe the phenomenon, including the different effects that the event has upon the audience and the stakeholders and benefits it has for them. It is one characteristic of The Passion that it allows for a variety of possible approaches, and this is, at the same time, part of its formula for success. Another characteristic is the configured intertextuality between the sacred biblical text and secular pop songs. In the second section, I will interpret this as a central mode of storytelling in The Passion. It can evoke traditional, but also new, interpretations of the Christian gospel. The purpose of the article is to interpret The Passion as an expression of constructive public theology. It is an example of how the gospel is brought into dialogue with secular society. Keywords: passion play; The Netherlands; public theology; intertextuality; The Passion 1. Introducing The Passion The television program The Passion is an example of public theology. -

The Bible in Music

The Bible in Music 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb i 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM The Bible in Music A Dictionary of Songs, Works, and More Siobhán Dowling Long John F. A. Sawyer ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London 115_320-Long.indb5_320-Long.indb iiiiii 88/3/15/3/15 66:40:40 AAMM Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by Siobhán Dowling Long and John F. A. Sawyer All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dowling Long, Siobhán. The Bible in music : a dictionary of songs, works, and more / Siobhán Dowling Long, John F. A. Sawyer. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8108-8451-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-8452-6 (ebook) 1. Bible in music—Dictionaries. 2. Bible—Songs and music–Dictionaries. I. Sawyer, John F. A. II. Title. ML102.C5L66 2015 781.5'9–dc23 2015012867 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. -

Snts 04-Apr 07-20Pgeid

All Saints Parish Paper MARGARET STREET, LONDON W.1 APRIL 2007 £1.00 VICARʼS LETTER of ceremonies. This was the part of the A couple of weeks ago, I was a guest at evening which I found least convincing. The an “Introduction to Christianity” in a answers were just too slick and obviously famous evangelical church in the City of rehearsed in advance. There was no chance London. I wasn’t entirely sure whether I for people to put their questions directly or had been invited to see how people could for any discussion. Everything was just too be introduced to Christianity — or because carefully controlled. someone thought I needed to be introduced What was impressive was the degree of to it myself. When asked in such circles, professionalism with which the event was “When did you become a Christian?”, I organised. The investment of time, money usually say, “When my parents took me to and effort must have been considerable. the font”. There must have been 150 people there although it was difficult to tell how The church had been set out with tables many were guests and how many regular and chairs and a very good meal was served members of the congregation. A number of to us — complete with wine — whatever these evenings are run each year. happened to evangelical horror of the demon drink? After the first course, there was a talk And then the following evening, there by the Rector — an exposition of the raising was something rather different: our own of Lazarus in John 11. -

The Production of Religious Broadcasting: the Case of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenGrey Repository The Production of Religious Broadcasting: The Case of the BBC Caitriona Noonan A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Cultural Policy Research Department of Theatre, Film and Television University of Glasgow Glasgow G12 8QQ December 2008 © Caitriona Noonan, 2008 Abstract This thesis examines the way in which media professionals negotiate the occupational challenges related to television and radio production. It has used the subject of religion and its treatment within the BBC as a microcosm to unpack some of the dilemmas of contemporary broadcasting. In recent years religious programmes have evolved in both form and content leading to what some observers claim is a “renaissance” in religious broadcasting. However, any claims of a renaissance have to be balanced against the complex institutional and commercial constraints that challenge its long-term viability. This research finds that despite the BBC’s public commitment to covering a religious brief, producers in this style of programming are subject to many of the same competitive forces as those in other areas of production. Furthermore those producers who work in-house within the BBC’s Department of Religion and Ethics believe that in practice they are being increasingly undermined through the internal culture of the Corporation and the strategic decisions it has adopted. This is not an intentional snub by the BBC but a product of the pressure the Corporation finds itself under in an increasingly competitive broadcasting ecology, hence the removal of the protection once afforded to both the department and the output. -

Friday 26Th February 2021 – Creative Space

THROUGH THE LENTEN DOOR A LOCKDOWN LENT COURSE FROM THE DIOCESE OF ABERDEEN& ORKNEY Friday 26th February 2021 – Creative Space Matthew 5:20-26 Jesus said 20 For I tell you, unless your righteousness exceeds that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven. 21 ‘You have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, “You shall not murder”; and “whoever murders shall be liable to judgement.” 22 But I say to you that if you are angry with a brother or sister, you will be liable to judgement; and if you insult a brother or sister, you will be liable to the council; and if you say, “You fool”, you will be liable to the hell of fire. 23 So when you are offering your gift at the altar, if you remember that your brother or sister has something against you, 24 leave your gift there before the altar and go; first be reconciled to your brother or sister, and then come and offer your gift. 25 Come to terms quickly with your accuser while you are on the way to court with him, or your accuser may hand you over to the judge, and the judge to the guard, and you will be thrown into prison. 26 Truly I tell you, you will never get out until you have paid the last penny. FRIDAY 26TH FEBRUARY Christ has no body now but yours. No hands, no feet on earth but yours. Yours are the eyes through which he looks compassion on this world. -

Passie in Het Publieke Domein Een Zoektocht Naar Een Verklaring Voor De 'Passiehype', Gebruik Makend Van Het Kader Van De Ritual Studies

Passie in het publieke domein Een zoektocht naar een verklaring voor de 'passiehype', gebruik makend van het kader van de Ritual Studies Masterscriptie voor de opleiding Religies in hedendaagse samenlevingen Faculteit Geesteswetenschappen Universiteit Utrecht M.C. den Boer (4152417) Supervisor: dr. N.M. Hijweege-Smeets Inhoudsopgave Samenvatting/Abstract 3. Inleiding 5. 1. Lijden in het publieke domein: vorm en inhoud van drie belangrijke verschijningsvormen van het lijdensverhaal van Jezus Christus 9. 1.1 Passie in de media 10. 1.2 De vorm van de drie verschijningsvormen van het lijdensverhaal van Jezus Christus 14. 1.2.1 De veertigdagentijd als rituele tijd 15. 1.2.2 Het ritueel-religieuze panorama van Post 18. 1.2.3 Het model van sacraal-rituele velden 23. 1.2.4 Samenvatting 27. 1.3 De inhoud van de drie verschijningsvormen van het lijdensverhaal van Jezus Christus 28. 1.3.1 Aandacht voor het lijden in het publieke domein 29. 1.3.2 Geloven in het publieke domein 32. 1.3.3 Samenvatting 36. 2. Waar vorm en inhoud samenkomen: het rituele karakter en het thema lijden verder uitgewerkt 37. 2.1 Leefstijlmaatschappij en zingeving 38. 2.2 De rol van heterotopie in rituelen 40. 2.2.1 Heterotopie: een definitie volgens Foucault 41. 2.2.2 Heterotopie in het model van Post 44. 2.3 De functie van rituelen: de visie van Whitehouse 47. 2.3.1 Hoe rituelen kunnen binden 48. 2.3.2 Waarom lijden bindt 52. 2.4 Waar vorm en inhoud samenkomen: rituelen rondom lijden tegen de achtergrond van de huidige maatschappij 55. -

Issue 52.Qxp

Issue 52 Summer 2011 Speen and North Dean News Guest Editor: Laura Blundell Advertising: Peter Cooper Production: Jude Awdry Committee: Gloria Holmes - Chair Tom Dent Megan Chinn Nick Wheeler-Robinson Julie White Printer: PK-Inprint Ltd Tel: 01494 452266 open after change of ownership & refurbishment GREAT FOOD, GREAT BEER, GREAT WINE, GREAT COFFEE - IN A TRADITIONAL PUB ENVIRONMENT The Pink and Lily has undergone a face lift: ‘The Pink’ has re-opened and has been revitalised. Come and enjoy excellent food AYLESBURY and drink at the pub Rupert Brooke, the 1st World War poet called his local. A41 Nestled in the Chilterns in Parslows Hillock, Lacey Green, this beautiful pub A418 dates back to the 1800s and is the ideal place to enjoy great beer and great food. A4010 A413 PRINCES RISBOROUGH M40 GREAT MISSENDEN M40 Open all day, every day HIGH WYCOMBE )UHVKORFDOO\VRXUFHGIRRGGDLO\ )RRGVHUYLFHSPSPDOOZHHN SPSP0RQGD\6DWXUGD\ *UHDWUDQJHRIUHDODOHVFKDQJLQJ TO PRINCES JXHVWEHHUVFRPSUHKHQVLYHZLQHOLVW RISBOROUGH TO )XQFWLRQERRNLQJVWDNHQ WARDROBES LANE GREAT PINK ROADMISSENDEN *UHDW6XQGD\URDVWVZLWKDOOWKHWULPPLQJV :HOONHSWJDUGHQ LILY BOTTOM LANE PINK ROAD 3LQN5RDG/DFH\*UHHQ3ULQFHV5LVERURXJK+35- TO HIGH teLQIR#SLQNDQGOLO\FRXNZZZSLQNDQGOLO\FRXN WYCOMBE OV5166 Contents Index of Advertisers What’s On . .4 Alan Tucker . .18 Letter from the Editor . .5 Speen and North Dean Toddler Group . .6 Alchemille . .23 Speen Pre-School . .7 Beechdean Farmhouse . .39 Speen School and PTA . .8 Speen Fun Day . .9 C.G. Tree & Garden Services . .29 The Ridgeway Walk 3 . .10 Chiltern House Partnership . .28 North Dean arrival . .11 Speen Fete . .13 Clare Foundation . .5 Speen Playing Fields . .14 Coles & Blackwell . .27 Speen Arts & Crafts Fair . .15 Photographic competition winners . -

This Lent, Every Catholic Church in the Diocese of Lancaster Will Be Open for Confession

FREE www.catholicvoiceoflancaster.co.uk The Official Newspaper to Inside this month: the Diocese of Lancaster p4 Olympic Fervour - Sports and Faith p10 Uclan Retreat to Pantasaph Issue 237 + March 2012 p12 Preston Passion The Light is ON for You Blog Bishop’s of courtesy Photo’ This Lent, every Catholic church in the Diocese of Lancaster will be open for Confession. Come and ollowing on from his New Year’s Day forgiveness “Confession gives us the chance FPastoral Letter and, as a preliminary to start over, to hit the ‘reset’ button of our Celebrate the to the upcoming Year of Faith (October lives. It shows how forgiving and Sacrament of 2012 to November 2013) announced by compassionate our God is and it helps us Pope Benedict XVI last year, Bishop to grow in concern and love for others. Come Reconciliation Campbell has launched an important to Confession this Lent and receive God’s - diocesan initiative this Lent called The mercy, for peace of mind and to deepen your Every Light Is On For You - a diocesan-wide friendship with Jesus, to receive spiritual Wednesday and high-profile celebration of the healing and to increase your sense of joy - Sacrament of Reconciliation. and to experience Christ’s saving grace.” 29th Every Wednesday of Lent, from 29th To those who feel it has been too long February February to the Wednesday of Holy Week, since their last confession or that God 4th April, every Catholic Church in the could not possibly forgive them, Bishop till the Diocese will be open from 7.00p.m. -

Table of Membership Figures For

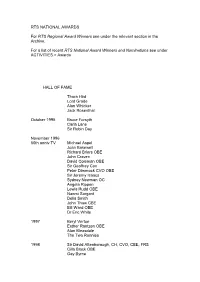

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

AREIAC NEWSLETTER from the Chair

ASSOCIATION OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION INSPECTORS, ADVISERS AND CONSULTANTS SUMMER 2017 AREIAC NEWSLETTER From the Chair... Jane Brooke Welcome from the new chair What does a SACRE do and who is on Edition Contents it? From the Chair 1 ‘What does a SACRE do and who is on it?’ Commission on RE: I was asked by a teacher who was about to further questions? 3 start some consultancy work to support The Manchester Passion 2017 5 SACRE. I realised that there was a large gap between the classroom and Religions are not Monoliths 7 consultancy in RE. Not surprisingly, he had - Classical Islam 7 little understanding of the role of SACRE or - Liberal Christianity 10 the legal requirements of RE. When a Accredited Resources for the teacher becomes a consultant, suddenly there is much more to Understanding Christianity learn about RE. In the last newsletter I commented upon the specific and unique role of RE Advisers. One role is to support Project 13 teachers through CPD and to encourage leadership to grow new Book Reviews 14 generations of RE professional leaders. Back Page 16 With the decline of many Local Authorities the post of RE advisers, has declined too and often, high quality classroom practitioners are appointed as consultants to SACREs for a number of days during the year. When I was first appointed as an adviser in a local authority, I had an induction process which included visiting a few Primary Schools, completing a personal skills audit to understand how I should develop professionally and observing colleagues delivering CPD to teachers. -

Corporate Responsibility & Partnerships 2006

CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY & PARTNERSHIPS 2006 REVIEW CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY AND PARTNERSHIPS 2006 Introduction 03 Serving audiences 04 Bringing people together 05 Sustaining citizenship 08 Reflecting diversity 10 Listening to our audiences 12 Communities 15 Promoting learning 17 Charity appeals 19 Working with children 22 Going local 25 Taking to the streets 27 Building bridges 30 BBC & the world 32 World Service Trust 33 Bringing countries together 35 Bringing the world to the UK 37 Partnerships 38 Sport 40 Homelessness 42 Arts 44 Broadcasting 46 Volunteering 48 The environment 49 Our output 52 In the workplace 54 Going green 57 Our business 5 8 Diversity in the workplace 59 Training 62 Suppliers 63 Outsourcing 64 CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY AND Back to Index PARTNERSHIPS 2006 This is our first online review of Corporate Responsibility and Partnerships at the BBC. We hope it will give a flavour of what we are doing and the importance that we place on the key issues. We have a strong tradition of Corporate Responsibility; in fact our responsibilities are explicitly stated in our new Charter. The new title we have given to this work is BBC Outreach. This review will aim to shine a spotlight on some of the best examples of outreach during 2006. We have divided it into sections that we think are most relevant to our business. It will certainly not address every subject and every story, but there are plenty of links provided if you want to get some more detailed information. We will be updating the content on a regular basis to make sure it always reflects what we are doing. -

3. Political Receptions of the Bible Since 1968 10 A

SCRIPTURAL TRACES: CRITICAL PERSPECTIVES ON THE RECEPTION AND INFLUENCE OF THE BIBLE 2 Editors Claudia V. Camp, Texas Christian University W. J. Lyons, University of Bristol Andrew Mein, Westcott House, Cambridge Editorial Board Michael J. Gilmour, David Gunn, James Harding, Jorunn Økland Published under LIBRARY OF NEW TESTAMENT STUDIES 506 Formerly Journal for the Study of the New Testament Supplement Series Editor Mark Goodacre Editorial Board John M. G. Barclay, Craig Blomberg, R. Alan Culpepper, James D. G Dunn, Craig A. Evans, Stephen Fowl, Robert Fowler, Simon J. Gathercole, John S. Kloppenborg, Michael Labahn, Robert Wall, Steve Walton, Robert L. Webb, Catrin H. Williams HARNESSING CHAOS The Bible in English Political Discourse Since 1968 James G. Crossley LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury is a registered trade mark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2014 © James G. Crossley, 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. James G. Crossley has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identi¿ed as Author of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author.