RESILIENT BUSINESS for RESILIENT NATIONS and COMMUNITIES Foreword

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEN Supply Chain Security (SCS) Feasibility Study

CEN Supply Chain Security (SCS) Feasibility study CEN/TC 379 Supply Chain Security Final report 15.1.2010 Hintsa J., Ahokas J., Männistö T., Sahlstedt J. Cross-border Research Association, Lausanne, Switzerland CEN SCS Feasibility study 2010 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report presents the outcomes of a feasibility study on supply chain operator needs for a possible European standard in supply chain security (SCS). The study was commissioned by the European Committee for Standardization, CEN, and funded by European Commission Directorate-General Energy and Transport, DG TREN. The study was carried out by four researchers at a Lausanne, Switzerland, based research institute, Cross-border Research Association, CBRA. The study process consisted of the following steps : (i) Literature review, where a large number of relevant publications were covered; (ii) Expert interviews, with 21 experts in supply chain, security and/or standardization; (iii) In-depth analysis of standards, covering four existing SCS standards and one regulation; and (iv) Operator survey, where 86 European supply chain operators shared their views on various SCS aspects, including the feasibility of a set of standard ideas, derived from the expert interviews. SCS is often considered to be a combination of crime prevention, security engineering, risk management, and operations management disciplines, i.e. part of social and engineering sciences. However, this study explores SCS in a broader context , covering some political and emotional factors, hypes and myths, some misconceptions and unrealistic expectations, and the interpretation of different schools of thought concerning priorities and most cost efficient ways to combat crime in supply chains. This study reveals relevant knowns and some unknowns about designing and implementing security in supply chains, including several concerns and complexities related to the development of SCS standards in Europe (and internationally). -

ZN TIL NR 51 2014 Reszka.Vp:Corelventura

Recenzenci Christiane Bielefeldt, Günter Emberger, Pieter van Essen, David B. Grant, Andrzej Grzelakowski, Mariusz Jedliñski, Miroslav Jeraj, Danuta Kempny, Barbara Kos, Xenie Lukoszová, Benedikt Mandel, El¿bieta Marciszewska, Vlastimil Melichar, Simon Shepherd, El¿bieta Za³oga Redaktor Wydawnictwa Stanis³awa Grzelczak Projekt ok³adki i stron tytu³owych Andrzej Taranek Sk³ad komputerowy i ³amanie Urszula Jêdryczka Publikacja sfinansowana z dochodów w³asnych Wydzia³u Ekonomicznego oraz funduszu dzia³alnoœci statutowej Katedry Logistyki Uniwersytetu Gdañskiego Wersj¹ pierwotn¹ publikacji jest wersja drukowana Udzielona licencja Open Access ãCopyright by Uniwersytet Gdañski Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdañskiego ISSN 0208-4821 Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdañskiego ul. Armii Krajowej 119/121, 81-824 Sopot tel./fax 58 523 11 37, tel. 725 991 206 e-mail: [email protected] www.wyd.ug.edu.pl Ksiêgarnia internetowa: www.kiw.ug.edu.pl SPIS TREŒCI WPROWADZENIE .............................................. 9 INTRODUCTION KONCEPCJE LOGISTYCZNE MAREK CIESIELSKI KRYTYCZNE PROBLEMY METODOLOGICZNE W BADANIACH NAD ZARZ¥DZANIEM £AÑCUCHAMI DOSTAW ..................... 15 CRITICAL METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS IN THE RESEARCH ON SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT HALINA BRDULAK POSZUKIWANIE NOWYCH PARADYGMATÓW W ZARZ¥DZANIU £AÑCUCHEM DOSTAW W WARUNKACH STAGNACJI GOSPODARCZEJ . 23 SEARCHING FOR NEW PARADIGMS IN SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT IN TERMS OF ECONOMIC STAGNATION MIROS£AW CHABEREK LOGISTYCZNE UWARUNKOWANIA PROINNOWACYJNYCH RELACJI W £AÑCUCHACH DOSTAW ..................................... -

Success Codes

a Volume 2, No. 4, April 2011, ISSN 1729-8709 Success codes • NTUC FairPrice CEO : “ International Standards are very important to us.” • Fujitsu innovates with ISO standards a Contents Comment Karla McKenna, Chair of ISO/TC 68 Code-pendant – Flourishing financial services ........................................................ 1 ISO Focus+ is published 10 times a year World Scene (single issues : July-August, November-December) International events and international standardization ............................................ 2 It is available in English and French. Bonus articles : www.iso.org/isofocus+ Guest Interview ISO Update : www.iso.org/isoupdate Seah Kian Peng – Chief Executive Officer of NTUC FairPrice .............................. 3 Annual subscription – 98 Swiss Francs Special Report Individual copies – 16 Swiss Francs A coded world – Saving time, space and energy.. ..................................................... 8 Publisher ISO Central Secretariat From Dickens to Dante – ISBN propels book trade to billions ................................. 10 (International Organization for Uncovering systemic risk – Regulators push for global Legal Entity Identifiers ..... 13 Standardization) No doubt – Quick, efficient and secure payment transactions. ................................. 16 1, chemin de la Voie-Creuse CH – 1211 Genève 20 Vehicle ID – ISO coding system paves the way for a smooth ride ........................... 17 Switzerland Keeping track – Container transport security and safety.. ....................................... -

ECSO State of the Art Syllabus V1 ABOUT ECSO

STATE OF THE ART SYLLABUS Overview of existing Cybersecurity standards and certification schemes WG1 I Standardisation, certification, labelling and supply chain management JUNE 2017 ECSO State of the Art Syllabus v1 ABOUT ECSO The European Cyber Security Organisation (ECSO) ASBL is a fully self-financed non-for-profit organisation under the Belgian law, established in June 2016. ECSO represents the contractual counterpart to the European Commission for the implementation of the Cyber Security contractual Public-Private Partnership (cPPP). ECSO members include a wide variety of stakeholders across EU Member States, EEA / EFTA Countries and H2020 associated countries, such as large companies, SMEs and Start-ups, research centres, universities, end-users, operators, clusters and association as well as European Member State’s local, regional and national administrations. More information about ECSO and its work can be found at www.ecs-org.eu. Contact For queries in relation to this document, please use [email protected]. For media enquiries about this document, please use [email protected]. Disclaimer The document was intended for reference purposes by ECSO WG1 and was allowed to be distributed outside ECSO. Despite the authors’ best efforts, no guarantee is given that the information in this document is complete and accurate. Readers of this document are encouraged to send any missing information or corrections to the ECSO WG1, please use [email protected]. This document integrates the contributions received from ECSO members until April 2017. Cybersecurity is a very dynamic field. As a result, standards and schemes for assessing Cybersecurity are being developed and updated frequently. -

Iso 22301:2019

INTERNATIONAL ISO STANDARD 22301 Second edition 2019-10 Security and resilience — Business continuity management systems — Requirements Sécurité et résilience — Systèmes de management de la continuité d'activité — Exigences Reference number ISO 22301:2019(E) © ISO 2019 ISO 22301:2019(E) COPYRIGHT PROTECTED DOCUMENT © ISO 2019 All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester. ISO copyright office CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8 CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva Phone: +41 22 749 01 11 Fax:Website: +41 22www.iso.org 749 09 47 Email: [email protected] iiPublished in Switzerland © ISO 2019 – All rights reserved ISO 22301:2019(E) Contents Page Foreword ..........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................v Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................vi 1 Scope ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

En Iso 22300

Terminology in Crisis and Disaster Management CEN Workshop Agreement Georg Neubauer, AIT http://www.ait.ac.at Background . The FP7 project EPISECC develops a concept of a common information space including taxonomy building to improve interoperability between European crisis managers and stakeholders . EPISECC is mandated to provide the outcome of its research to international standardisation – involvement in CEN TC391 . Within the FP7 project DRIVER a standard on terminology in crisis management shall be developed (among multiple other goals) . DRIVER & EPISECC will jointly co-operate on this issue . Additional support is planned from the FP7 projects REDIRNET, SECINCORE and SECTOR (all dealing with interoperability) 2 Scope and Purpose . Provision of an overview of existing terminologies and definitions applied in multiple domains of crisis and disaster management . Overview on synonyms with the same or similar definitions . Overview on different definitions for the same term . Benefit: Support enhancement of mutual understanding of users/organizations applying different standards/taxonomies . Benefit: Potential long term perspective: enhanced use of most suitable terms and definitions arising from multiple sources 3 Scope and Purpose (Example) Domain Term Definition Standard/document Intended Users situation where widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses have occurred which exceeded the ability of the affected organization (2.2.9), community or society to respond and recover using its own resources Societal security disaster ISO 22300 (2012) not specified A serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses and impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own authorities, pratictioners not specified disaster resources. -

Risk Management in Crisis: Winners and Losers During the COVID-19 Pandemic/Piotr Jedynak and Sylwia Bąk

Risk Management in Crisis Risk management is a domain of management which comes to the fore in crisis. This book looks at risk management under crisis conditions in the COVID-19 pandemic context. The book synthesizes existing concepts, strategies, approaches and methods of risk management and provides the results of empirical research on risk and risk management during the COVID-19 pandemic. The research outcome was based on the authors’ study on 42 enterprises of different sizes in various sectors, and these firms have either been negatively affected by COVID-19 or have thrived successfully under the new conditions of conducting business activities. The anal- ysis looks at both the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the selected enter- prises and the risk management measures these enterprises had taken in response to the emerging global trends. The book puts together key factors which could have determined the enterprises’ failures and successes. The final part of the book reflects on how firms can build resilience in chal- lenging times and suggests a model for business resilience. The comparative anal- ysis will provide useful insights into key strategic approaches of risk management. Piotr Jedynak is Professor of Management. He works at Jagiellonian University in Cracow, Poland, where he holds the positions of Vice-Rector for Financial and HR Policy and Head of the Management Systems Department. He specializes in risk management, strategic management and management systems. He is the author of numerous publications, an auditor and consultant to many public and business organizations. Sylwia Bąk holds a PhD in Management Sciences. -

Tackling Counterfeit with ISO and IEC Standards

counterfeit Tackling counterfeit with IEC and ISO standards Tackling counterfeit with IEC and ISO standards In Roman times it was wine, in mediaeval times it was textiles and weapons, today it is everything from personal computers to potency pills. Counterfeit goods are nothing new, but with globalization, the Internet and increased movement of goods, the fakes business is booming. The global value of counterfeit goods was estimated as being worth between USD 923 billion and USD 1.13 trillion in 2016 alone 1), costing millions of jobs and funding further abuses such as corruption and violence. Counterfeit affects virtually every country in the world, fuels illegal activities and harms you and your family. Aircraft, automotive parts, medicines, toys, electronic equipment, clothing and foodstuffs are just some of the products tarnished by the counterfeit industry. IEC and ISO have dedicated committees working on standards and solutions to help combat counterfeit and provide increased confidence to consumers. These include standards that test for authenticity, provide guidelines to measure the competency of testing laboratories and provide quality and minimum safety guidelines. For electric and electronic goods, the IEC offers testing and certifica- tion services that assist in quality and supply chain management, ensuring that suppliers deliver authentic parts and end products are safe to use. 1) Global Financial Integrity Tackling counterfeit with IEC and ISO standards – 1 What exactly are counterfeit goods ? The World Trade Organization (WTO) defines product counterfeiting as the “ unauthorized representation of a registered trademark carried on goods identical or similar to goods for which the trademark is registered, with a view to deceiving the purchaser into believing that he/she is buying the origi- nal goods ”. -

Final Meeting Report 2011-1-12

ANSI Homeland Security Standards Panel Ninth Annual Plenary Meeting: U.S. – European Collaboration on Security Standardization Systems November 9-10, 2010 Final Meeting Report Sheraton National Hotel 900 South Orme Street Arlington, VA 22204 ANSI-HSSP Co-Chairs: th Chris Dubay, Vice President and Chief Engineer, Galaxy Ballroom, 16 Floor National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Gordon Gillerman, Director, Standards Services Group, National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Tuesday - November 9, 2010 Welcome/Opening Remarks Karen Hughes, Director, Homeland Security Standards, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) opened the meeting and welcomed the participants. Ms. Hughes began her remarks by acknowledging the support of Dr. Bert Coursey and his team at the Department of Homeland Security’s Science and Technology Directorate (DHS S&T), the ANSI-Homeland Security Standards Panel (ANSI-HSSP) co-chairs, Chris Dubay and Gordon Gillerman, and Dr. Alois Sieber and his team at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) in shaping the plenary program. Ms. Hughes provided a background on the ANSI-HSSP specifically noting that the ANSI-HSSP leverages public-private sector collaboration to address critical needs in standardization in the area of homeland security. Ms. Hughes added that this plenary meeting is an example of building on collaborative success, as this meeting resulted from a joint meeting between DHS and the JRC in April 2010. During this meeting the following four key priorities were identified for potential collaboration between the United States and Europe: aviation security standardization, borders and maritime security standardization, global supply chain security standardization, and preparedness and crisis management standardization, and the agenda of the plenary meeting adequately represents all of those areas. -

Linee Guida Per Lo Sviluppo E La Definizione Del Modello Nazionale

Linee guida per lo sviluppo e la definizione del modello nazionale di riferimento per i CERT regionali AGID 13 feb 2020 Indice 1 Premessa 3 2 Riferimenti 5 2.1 Leggi...................................................5 2.2 Linee Guida e Standard.........................................5 3 Definizioni e Acronimi 7 4 Contesto 9 4.1 Quadro di riferimento nazionale.....................................9 4.2 Impianto normativo applicabile ai CERT................................ 12 4.3 Organismi a supporto della Cyber Security............................... 18 4.4 Standard per la Cyber Security...................................... 21 5 Introduzione ai CERT 31 5.1 CERT: significato e definizioni generali................................. 31 5.2 Categorie di CERT............................................ 32 5.3 Mission dei CERT............................................ 32 5.4 Identificazione della constituency.................................... 33 5.5 CERT regionali.............................................. 34 6 Modello organizzativo 39 6.1 Modello indipendente.......................................... 39 6.2 Modello incorporato........................................... 41 6.3 Modello campus............................................. 43 7 Modello amministrativo 45 8 Servizi 47 8.1 Modelli di classificazione dei servizi.................................. 47 8.2 Servizi offerti dai CERT Regionali.................................... 50 9 Processo di gestione degli incidenti di sicurezza 57 9.1 Definizioni............................................... -

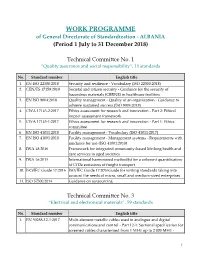

WORK PROGRAMME of General Directorate of Standardization - ALBANIA (Period 1 July to 31 December 2018)

WORK PROGRAMME of General Directorate of Standardization - ALBANIA (Period 1 July to 31 December 2018) Technical Committee No. 1 “Quality assurance and social responsibility”, 11 standards No. Standard number English title 1. EN ISO 22300:2018 Security and resilience - Vocabulary (ISO 22300:2018) 2. CEN/TS 17159:2018 Societal and citizen security - Guidance for the security of hazardous materials (CBRNE) in healthcare facilities 3. EN ISO 9004:2018 Quality management - Quality of an organization - Guidance to achieve sustained success (ISO 9004:2018) 4. CWA 17145-2:2017 Ethics assessment for research and innovation - Part 2: Ethical impact assessment framework 5. CWA 17145-1:2017 Ethics assessment for research and innovation - Part 1: Ethics committee 6. EN ISO 41011:2018 Facility management - Vocabulary (ISO 41011:2017) 7. EN ISO 41001:2018 Facility management - Management systems - Requirements with guidance for use (ISO 41001:2018) 8. IWA 18:2016 Framework for integrated community-based life-long health and care services in aged societies 9. IWA 16:2015 International harmonized method(s) for a coherent quantification of CO2e emissions of freight transport 10. ISO/IEC Guide 17:2016 ISO/IEC Guide 17:2016Guide for writing standards taking into account the needs of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises 11. ISO 37500:2014 Guidance on outsourcing Technical Committee No. 3 “Electrical and electronical materials”, 59 standards No. Standard number English title 1. EN 50288-12-1:2017 Multi-element metallic cables used in analogue and digital communications and control - Part 12-1: Sectional specification for screened cables characterised from 1 MHz up to 2 000 MHz - 1 Horizontal and building backbone cables 2. -

Attractions of Iso28000 for Security of Supply Chains

International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET) Volume 9, Issue 9, September 2018, pp. 421–427, Article ID: IJMET_09_09_046 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJMET?Volume=9&Issue=9 ISSN Print: 0976-6340 and ISSN Online: 0976-6359 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed ATTRACTIONS OF ISO28000 FOR SECURITY OF SUPPLY CHAINS Constantin Gehling ESB Business School, Reutlingen University, Germany Shahryar Sorooshian Faculty of Industrial Management & Centre for Earth Resources Research and Management, Universiti Malaysia Pahang, Malaysia ABSTRACT This research investigates the benefits that encourage implementation of ISO28000 security management systems for Supply chains. Hence, a list of benefits is presented from exploring published journals as a literature review. The journal articles and books investigated ISO standards were used due to the lack of literature on ISO28000. A list of benefits was developed. Since there is no list of benefits of implementing security management systems to be found in the literature, the proposed list fills the gap in literature. The findings of the study can be used in future research to explore ways to lift the supply chains with encouraging the implementation of ISO28000. Key words: Benefits, Supply chain, ISO28000 Implementation, Security. Cite this Article: Constantin Gehling and Shahryar Sorooshian, Attractions of ISO28000 for Security of Supply Chains, International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology 9(9), 2018, pp. 421–427. http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJMET?Volume=9&Issue=9 1. INTRODUCTION ISO28000 was first introduced in 2005 as ISO/PAS 28000:2005, but has since been revised by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). The aim of this standard is to provide the requirements for an organization to implement, improve, maintain and establish a security management system [1,2].