Geographica 14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Brooklyn Community Board #4 Regular Monthly Meeting

Brooklyn Community Board #4 Regular Monthly Meeting Wednesday, October 17, 2018 Hope Gardens Multi Service Center 195 Linden Street Brooklyn, New York 11221 6:00PM The Brooklyn Community Board #4 October 17, 2018 Meeting. The Chairperson, Mr. Robert Camacho opened the monthly Community Board #4 meeting at 6:05PM - Agenda Items – 1) Naila Caicedo-Rosario, Intergovernmental Affairs Brooklyn Public Library & Jordon Bullard, Project Manager for Culture Pass – Presentation on the NYC Culture Pass Initiative What is Culture Pass? Culture Pass is a program for cardholding patrons ages 13 and older of Brooklyn Public Library, The New York Public Library and Queens Library. Using their library card, New Yorkers can reserve a pass and get free admission to dozens of NYC culture institutions, including museums, historical societies, heritage centers, public gardens and more. How do I get a Pass? Log in with your library card credentials and browse for passes by date or venue. Make your reservation and print or download your pass shortly before your visit. Note that once you print or download your pass you cannot cancel your reservation. Discover your City with Culture Pass. Explore New York City’s museums and attractions with Culture Pass. If you have a library card, you can get free admission to dozens of cultural institutions. Save money and discover more about your city!!! How many passes can you reserve? You can reserve one pass per cultural institution per calendar year and you can have two concurrent reservations per card. Having two active reservations will block you from making additional bookings for future dates. -

Conor Tomás Reed [email protected]

Conor Tomás Reed [email protected] EDUCATION DISSERTATION-IN-PROGRESS: CUNY Will Be Free!: Black, Puerto Rican, and Women’s Compositions, Literatures, and Studies at the City College of New York and New York City, 1960-1980 ADVISORS: Ammiel Alcalay, Robert Reid-Pharr, Ira Shor 2016 M.PHIL., English Literature, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York 2012 The Free University of New York City, co-founding participant 2010 B.A., English Literature, Harlem University/The City College of New York PROFESSIONAL WORK ❖ Scholar-in-Residence and Archival Dissertation Fellow, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Fall 2016–Spring 2017. ❖ Kingsborough Community College/CUNY, Graduate Writing Fellow and Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) Certification, Fall 2015–Spring 2016. ❖ CUNY Graduate Center, Library Assistant, Mina Rees Library, Fall 2014–Spring 2016. ❖ Medgar Evers College/CUNY, Adjunct Lecturer, English Department, Fall 2014. ❖ Medgar Evers College/CUNY, Graduate Teaching Fellow, English Department, Fall 2013–Spring 2014. ❖ American Studies Association, Principal Researcher on 2014 Scholars Under Attack Digital Map for American Studies Association Conference, November 2014. ❖ Baruch College/CUNY, Graduate Teaching Fellow, English Department, Spring 2011–Spring 2013. ❖ Adjunct Project, Co-Coordinator of Education and Advocacy, Spring 2011–Spring 2013. ❖ LaGuardia Community College/CUNY, Adjunct Lecturer, English Department, Fall 2010. TEACHING THEMES 20th and 21st century U.S., Caribbean, and Latin American literatures; African American literatures; women’s literatures; urban composition-literacies; social movements poetics and fiction; American studies; cultural studies; labor histories; educational reform and transformation histories. HONORS/AWARDS ❖ Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Dissertation Grant, 2017–2018. ❖ Summer Research Travel Fellowship by the Center for Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies (CLACLS) at the CUNY Graduate Center, 2017. -

Performing Arts No Matter Your Taste, There’S a Creative Expression in This Melting Pot That Will Cater to It

SPACES & PLACES: The 16-acre campus of Lincoln Center offers “a complete detachment from the hustle and bustle of the city, where you can just be immersed in a performance—ballet, opera, symphony, and others,” says Barbara Grossman Berger ’77, who cochairs the New York Metro Women and is a member of the Metro New York City Network Leadership Cabinet. 20 ROCHESTER REVIEW July–August 2018 RochRev_July2018.indb 20 7/30/18 4:31 PM INSIDE VIEW: “Part of what gives you that insider’s view of New York,” says fourth-generation New Yorker Noah Pizmony-Levy Drezner ’00, “is that you can actually step back to see it from afar and appreciate where we are.” Show Us Your Town There are lots of reasons New York draws 62.8 million visitors annually. But the 14,000 alumni who call themselves locals know the teeming city as much more than a tourist attraction. By Robin L. Flanigan Minutes after the ferry horn blares, Noah Pizmony- It’s one of 11 regional networks—and the second Levy Drezner ’00 nods toward his destination, largest—initially identified as part of a strategic ef- Governors Island, a national monument in the fort to build a stronger sense of connection among heart of New York Harbor. Rochester’s key constituencies. “This place is a hidden gem,” says the fourth-gen- Over three days, Pizmony-Levy Drezner and eration New Yorker, who goes to the island often other members of the Rochester community en- for concerts or just for a tranquil respite from the thusiastically offered an insider’s peek at a city cap- commotion of the city. -

"Bushwick Es Mio:" Gentrification and the Emotional Displacement of Latinas

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2014 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2014 "Bushwick was Mine," "Bushwick es mio:" Gentrification and the Emotional Displacement of Latinas Rosemary Ferreira Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2014 Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Ferreira, Rosemary, ""Bushwick was Mine," "Bushwick es mio:" Gentrification and the Emotional Displacement of Latinas" (2014). Senior Projects Spring 2014. 12. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2014/12 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Bushwick was Mine,” “Bushwick es mio”: Gentrification and the Emotional Displacement of Latinas Senior Project submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Rosemary Ferreira Annandale-on-Hudson, New York April 2014 For my mother, Maria Ferreira, And for all immigrant women, Whose calloused hands and broken backs Carried us to where we stand now Acknowledgements To the women who participated in this study, thank you. This project would not have touched me as greatly if I had not thought of it as a platform to share your resilient stories. -

Report Measures the State of Parks in Brooklyn

P a g e | 1 Table of Contents Introduction Page 2 Methodology Page 2 Park Breakdown Page 5 Multiple/No Community District Jurisdictions Page 5 Brooklyn Community District 1 Page 6 Brooklyn Community District 2 Page 12 Brooklyn Community District 3 Page 18 Brooklyn Community District 4 Page 23 Brooklyn Community District 5 Page 26 Brooklyn Community District 6 Page 30 Brooklyn Community District 7 Page 34 Brooklyn Community District 8 Page 36 Brooklyn Community District 9 Page 38 Brooklyn Community District 10 Page 39 Brooklyn Community District 11 Page 42 Brooklyn Community District 12 Page 43 Brooklyn Community District 13 Page 45 Brooklyn Community District 14 Page 49 Brooklyn Community District 15 Page 50 Brooklyn Community District 16 Page 53 Brooklyn Community District 17 Page 57 Brooklyn Community District 18 Page 59 Assessment Outcomes Page 62 Summary Recommendations Page 63 Appendix 1: Survey Questions Page 64 P a g e | 2 Introduction There are 877 parks in Brooklyn, of varying sizes and amenities. This report measures the state of parks in Brooklyn. There are many different kinds of parks — active, passive, and pocket — and this report focuses on active parks that have a mix of amenities and uses. It is important for Brooklynites to have a pleasant park in their neighborhood to enjoy open space, meet their neighbors, play, and relax. While park equity is integral to creating One Brooklyn — a place where all residents can enjoy outdoor recreation and relaxation — fulfilling the vision of community parks first depends on measuring our current state of parks. This report will be used as a tool to guide my parks capital allocations and recommendations to the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks), as well as to identify recommendations to improve advocacy for parks at the community and grassroots level in order to improve neighborhoods across the borough. -

In New York City

Outdoors Outdoors THE FREE NEWSPAPER OF OUTDOOR ADVENTURE JULY / AUGUST / SEPTEMBER 2009 iinn NNewew YYorkork CCityity Includes CALENDAR OF URBAN PARK RANGER FREE PROGRAMS © 2009 Chinyera Johnson | Illustration 2 CITY OF NEW YORK PARKS & RECREATION www.nyc.gov/parks/rangers URBAN PARK RANGERS Message from: Don Riepe, Jamaica Bay Guardian To counteract this problem, the American Littoral Society in partnership with NYC Department of Parks & Recreation, National Park Service, NYC Department of Environmental Protection, NY State Department of Environmental Conservation, Jamaica Bay EcoWatchers, NYC Audubon Society, NYC Sierra Club and many other groups are working on various projects designed to remove debris and help restore the bay. This spring, we’ve organized a restoration cleanup and marsh planting at Plum Beach, a section of Gateway National Recreation Area and a major spawning beach for the ancient horseshoe crab. In May and June during the high tides, the crabs come ashore to lay their eggs as they’ve done for millions of years. This provides a critical food source for the many species of shorebirds that are migrating through New York City. Small fi sh such as mummichogs and killifi sh join in the feast as well. JAMAICA BAY RESTORATION PROJECTS: Since 1986, the Littoral Society has been organizing annual PROTECTING OUR MARINE LIFE shoreline cleanups to document debris and create a greater public awareness of the issue. This September, we’ll conduct Home to many species of fi sh & wildlife, Jamaica Bay has been many cleanups around the bay as part of the annual International degraded over the past 100 years through dredging and fi lling, Coastal Cleanup. -

Voters Guide

VOTING ENDS September 30, 2017 FREE 2018 VOTERS GUIDE VOTE FOR THE BEST BUSINESSES IN BROOKLYN NOMINATED BY YOU! 2,000+ BUSINESSES 175+ CATEGORIES PRODUCED BY SCHNEPS COMMUNICATIONS FOLLOW US ENJOY THE FREE LIFE. FREE CHECKING AND A FREE GIFT! Get a free gift1 when you you open any Perfectly Free Checking account. 800.321.DIME (3463) • dime.com Dime Community Bank 1 We reserve the right to substitute a gift of similar value. Free gift provided at time of account opening. Free gift may be reported on a 1099-INT or 1099-MISC. Limit of one new checking account opened per customer receiving a free gift. Other fees such as for non-sufficient funds, overdraft, etc. may apply. See Schedule of Service Charges for details. Bank rules and regulations apply. Minimum opening deposit is only $25. Ask us for details. 2 BEST OF BROOKLYN 2018 • VOTERS GUIDE • BESTOFBK.COM Congratulations to all of the businesses that have been nominated for the 2018 Dime Best of Brooklyn awards. The nominees were selected by Brooklyn residents and each exemplifies excellence in the category for which they were nominated. Dime Community Bank is proud to be the Naming Sponsor of the Dime Best of Brooklyn program. In partnering with Best of Brooklyn, we are delighted to showcase and highlight this magnificent borough’s small businesses, a core part of our vibrant and growing communities. The voting period is already underway and we look forward to crowning the Dime Best of Brooklyn winners for 2018. Just like the businesses nominated, Dime has deep Brooklyn roots tracing our history back to 1864 in Williamsburg. -

New Year's Blasts!

Jan. 8–14, 2016 Including Park Slope Courier, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Courier, Brooklyn Heights Courier, & Williamsburg Courier FREE INTEGRATEDSERVING GOWANUS, PARK SLOPE, PROSPECT HEIGHTS, WINDSOR TERRACE, BROOKLYN HEIGHTS, DUMBO, METROTECH, BOERUM HILL, CARROLL GARDENS, COBBLE HILL, RED HOOK, WILLIAMSBURG & GREENPOINT City OKs move of white kids into mostly minority school BY LAUREN GILL The city will to go ahead with a controversial plan to ex- pand a Vinegar Hill elemen- tary school zone next year to New include students from Dumbo, Photo by Louise Wateridge after a panel of public school FOOD SWAP: Locals are concerned parents voted last Tuesday to Year’s that this Key Foods at Fifth Avenue approve the scheme. will go the way of the dodo. Members of the local com- munity education council voted 6–3 in favor, despite ob- blasts! Grocery for jections from families in both neighborhoods that the educa- tion department is rushing in without considering what will new Slope happen when it pushes a bunch of wealthy white kids into a school that serves mostly mi- Key Food nority students — concerns “yes” voters said were moti- vated by fear, not what’s best complex for the kids. “When our kids go to BY COLIN MIXSON school, they’re not thinking It is almost a lock. about whether or not Johnny A developer that plans on or Shaniqua has two different erecting a new building on color skins, they’re thinking the site of Park Slope’s beloved about learning and playing,” Fifth Avenue Key Food will al- said panel member Vascilla most certainly install another Caldeira, whose kids attend grocery store in the new com- PS 20 in Fort Greene. -

1 Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY of CONGRESS

Before the U.S. COPYRIGHT OFFICE, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS In the Matter of Exemption to Prohibition on Circumvention of Copyright Protection Systems for Access Control Technologies Under 17 U.S.C. §1201 Docket No. 2014-07 Reply Comments of the Electronic Frontier Foundation 1. Commenter Information Mitchell L. Stoltz Corynne McSherry Kit Walsh Electronic Frontier Foundation 815 Eddy St San Francisco, CA 94109 (415) 436-9333 [email protected] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is a member-supported, nonprofit public interest organization devoted to maintaining the traditional balance that copyright law strikes between the interests of rightsholders and the interests of the public. Founded in 1990, EFF represents over 25,000 dues-paying members, including consumers, hobbyists, artists, writers, computer programmers, entrepreneurs, students, teachers, and researchers, who are united in their reliance on a balanced copyright system that ensures adequate incentives for creative work while promoting innovation, freedom of speech, and broad access to information in the digital age. In filing these reply comments, EFF represents the interests of the many people in the U.S. who have “jailbroken” their cellular phone handsets and other mobile computing devices—or would like to do so—in order to use lawfully obtained software of their own choosing, and to remove software from the devices. 2. Proposed Class 16: Jailbreaking – wireless telephone handsets Computer programs that enable mobile telephone handsets to execute lawfully obtained software, where circumvention is accomplished for the sole purposes of enabling interoperability of such software with computer programs on the device or removing software from the device. 1 3. -

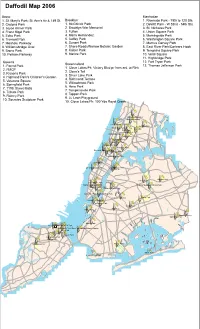

Daffodil Map 2006

Daffodil Map 2006 Bronx Manhattan 1. St. Mary's Park; St. Ann's Av & 149 St. Brooklyn 1. Riverside Park - 79th to 120 Sts. 2. Crotona Park 1. McGolrick Park 2. DeWitt Park - W 52nd - 54th Sts. 3. Joyce Kilmer Park 2. Brooklyn War Memorial 3. St. Nicholas Park 4. Franz Sigel Park 3. Fulton 4. Union Square Park 5. Echo Park 4. Maria Hernandez 5. Morningside Park 6. Tremont Park 5. Coffey Park 6. Washington Square Park 7. Mosholu Parkway 6. Sunset Park 7. Marcus Garvey Park 8. Williamsbridge Oval 7. Shore Roads/Narrow Botanic Garden 8. East River Park/Corlears Hook 9. Bronx Park 8. Kaiser Park 9. Tompkins Square Park 10. Pelham Parkway 9. Marine Park 10. Verdi Square 11. Highbridge Park Queens 12. Fort Tryon Park Staten Island 1. Forest Park 13. Thomas Jefferson Park 1. Clove Lakes Pk; Victory Blvd pr from ent. to Rink 2. FMCP 2. Clove's Tail 3. Kissena Park 3. Silver Lake Park 4. Highland Park's Children's Garden 4. Richmond Terrace 5. Veterans Square 5. Willowbrook Park 6. Springfield Park 6. Hero Park 7. 111th Street Malls 7. Tompkinsville Park 8. Tribute Park 8. Tappen Park 9. Rainey Park 9. Lt. Leah Playground 10. Socrates Sculpture Park 10. Clove Lakes Pk: 100 Yds Royal Creek Williamsbridge Oval Mosholu Parkway Fort Tryon Park Pelham Pkwy Highbridge Park Bronx Park Echo Park Tremont Park Highbridge Park Crotona Park Joyce Kilmer Park Franz Sigel Park St Nicholas Park St Mary's Park Riverside PMaorkrningside Park Marcus Garvey Park Thomas Jefferson Park Verdi Square De Witt Clinton Park Socrates Sculpture Garden Rainey Park Kissena Park 111th Street Malls Union Square Park Washington Square Park Flushing Meadows Corona Park Tompkins Square Park Monsignor Mcgolrick Park East River Park/Corlears Hook Park Maria Hernandez Park Forest Park Brooklyn War Memorial Fort Greene Park Highland Park Coffey Park Fulton Park Veterans Square Springfield Park Sunset Park Richmond TLetr.ra Nceicholaus Lia Plgd. -

Annual Report 2018

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 DEPARTMENT OF EPIDEMIOLOGY AND GLOBAL HEALTH Annual Report 2018 DEPARTMENT OF EPIDEMIOLOGY AND GLOBAL HEALTH Umeå International School of Public Health (UISPH) Umeå Centre for Global Health Research (UCGHR) Printed by Cityprint i Norr AB, Umeå, Sweden 2019 Prologue To all staff, students, collaborators and other colleagues, The year 2018 will be remembered as one of change and ongoing commitment! After more than three decades in our “old” house we moved to a new location. This was a big step to take and much of the hard work was done by our “Moving Group” to ensure as smooth a process as possible. In April we closed the doors of the old house and have since settled and started to feel at home in our new building. During the year we also paved the way to become a department in our own right, after previously being a unit and part of the larger department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine. In December the decision was taken by the University Board to form the Department of Epidemiology and Global Health from 1st of January 2019: “This change aims to create an interdisciplinary research and educational environment that contributes to a global and sustainable improvement regarding health and welfare.” We will continue to strengthen our activities involving collaboration in both teaching and research. We are located in the Region of Västerbotten and the wealth of experience and creative collaboration within the Region connects us to international collaborations around the world. Public health is based on the principles of equity, social justice, participation, and evidence-informed practice. -

Brooklyn Farmers Markets

Use Your EBT Card at a Farmers Market Brooklyn Farmers Markets 15 Flatbush Junction Youthmarket 31 McCarren Park Greenmarket Greenpoint Nostrand & Flatbush Aves. Union Ave. bet. Driggs & N. 12th Sts. y • Saturday (8:30 a.m. - 2 p.m.) • Saturday (8 a.m. - 2 p.m.) 32 x w s E en ue Q n 16 Fort Greene Park Greenmarket 32 McGolrick Park’s Down to Earth 31 ly Wi ok llia ro M ms B Washington Park bet. Dekalb Ave. Farmers Market anhattan Br bur g Br North Side Broo dg & Willoughby St. Russell St. & Nassau Ave., South Side kl yn East • Saturday (8 a.m. - 3 p.m.) center of park Br Br 42 oad Williamsburg dg dg w Fulton Vinegar ay • Sunday 10 a.m. - 4 p.m.) Ferry Hill 17 36 17 Graham Ave. Farmers Market H 44 L 37 33 C Flushing Av Bushwick Cook St. & Graham Ave. Park Slope’s Down to Earth a Brooklyn Heights r e Clinton • Saturday (8 a.m. - 5 p.m.) Farmers Market y 7 T Hill u 16 n Downtown 23 4th St. & 5th Ave. n 24 38 e Fort 20 18 Grand Army Plaza Greenmarket l Cobble Hill Greene Bedford Stuyvesant • Sunday (10 a.m. - 5 p.m.) Boerum Hill Flatbush Ave. & Prospect Park W., 9 Highland Park 11 at Prospect Park’s N.W. Entrance 34 Pitkin Verde Farmers Market Prospect 41 Broadway Atlantic Av City Line Red Hook 40 Heights Junction • Saturday (8 a.m. - 4 p.m.) 2094 Pitkin Ave. Gowanus 19 Weeksville 39 33 Park 18 • Tuesday (9 a.m.