Millercoors V. Anheuser-Busch Cos., LLC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read H. C. Hirschboeck Autobiography

AUTOBIOGRAPHY HERBERT C. HIRSCHBOECK Copr. 1981 H.C. Hirschboeck TO MERT AUTOBIOGRAPHY HERBERT C. HIRSCHBOECK Page No. 1. Early Years .......................................... 2 2. After High School .................................... 6 3. Amateur Theater ...................................... 11 4. After Law School ..................................... 13 5. Beginning Law Practice ............................... 17 6. Europe ............................................... 20 7. Dunn & Hirschboeck ................................... 25 8. Early Supreme Court Appeals .......................... 26 9. The Depression ....................................... 34 10. City Attorney's Office .............................. 36 11. Baby Bonds .......................................... 49 12. Miller, Mack & Fairchild ............................ 56 13. Marriage ............................................ 60 14. Return to Individual Practice ....................... 68 15. Cancer .............................................. 74 16. Hirschboeck & McKinnon .............................. 77 17. Thorp Finance Corporation ........................... 79 18. John Smith .......................................... 83 19. World War II ........................................ 86 20. Whyte & Hirschboeck ................................. 90 21. New Associates and Partners ......................... 95 22. Michael and John Cudahy ............................. 97 23. Milwaukee Bar Association ........................... 100 24. Miller Brewing Company ............................. -

Blue Moon Belgian White Witbier / 5.4% ABV / 9 IBU / 170 CAL / Denver, CO Anheuser-Busch Bud Light Lager

BEER DRAFT Blue Moon Belgian White Pint 6 Witbier / 5.4% ABV / 9 IBU / 170 CAL / Denver, CO Pitcher 22 Blue Moon Belgian White, Belgian-style wheat ale, is a refreshing, medium-bodied, unfiltered Belgian-style wheat ale spiced with fresh coriander and orange peel for a uniquely complex taste and an uncommonly... Anheuser-Busch Bud Light Pint 6 Lager - American Light / 4.2% ABV / 6 IBU / 110 CAL / St. Louis, Pitcher 22 MO Bud Light is brewed using a blend of premium aroma hop varieties, both American-grown and imported, and a combination of barley malts and rice. Its superior drinkability and refreshing flavor... Coors Coors Light Pint 5 Lager - American Light / 4.2% ABV / 10 IBU / 100 CAL / Pitcher 18 Golden, CO Coors Light is Coors Brewing Company's largest-selling brand and the fourth best-selling beer in the U.S. Introduced in 1978, Coors Light has been a favorite in delivering the ultimate in... Deschutes Fresh Squeezed IPA Pint 7 IPA - American / 6.4% ABV / 60 IBU / 192 CAL / Bend, OR Pitcher 26 Bond Street Series- this mouthwatering lay delicious IPA gets its flavor from a heavy helping of citra and mosaic hops. Don't worry, no fruit was harmed in the making of... 7/2/2019 DRAFT Ballast Point Grapefruit Sculpin Pint 7 IPA - American / 7% ABV / 70 IBU / 210 CAL / San Diego, CA Pitcher 26 Our Grapefruit Sculpin is the latest take on our signature IPA. Some may say there are few ways to improve Sculpin’s unique flavor, but the tart freshness of grapefruit perfectly.. -

Big Beer Duopoly a Primer for Policymakers and Regulators

Big Beer Duopoly A Primer for Policymakers and Regulators Marin Institute Report October 2009 Marin Institute Big Beer Duopoly A Primer for Policymakers and Regulators Executive Summary While the U.S. beer industry has been consolidating at a rapid pace for years, 2008 saw the most dramatic changes in industry history to date. With the creation of two new global corporate entities, Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI) and MillerCoors, how beer is marketed and sold in this country will never be the same. Anheuser-Busch InBev is based in Belgium and largely supported and managed by Brazilian leadership, while MillerCoors is majority-controlled by SABMiller out of London. It is critical for federal and state policymakers, as well as alcohol regulators and control advocates to understand these changes and anticipate forthcoming challenges from this new duopoly. This report describes the two industry players who now control 80 percent of the U.S. beer market, and offers responses to new policy challenges that are likely to negatively impact public health and safety. The new beer duopoly brings tremendous power to ABI and MillerCoors: power that impacts Congress, the Office of the President, federal agencies, and state lawmakers and regulators. Summary of Findings • Beer industry consolidation has resulted in the concentration of corporate power and beer market control in the hands of two beer giants, Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI) and MillerCoors LLC. • The American beer industry is no longer American. Eighty percent of the U.S. beer industry is controlled by one corporation based in Belgium, and another based in England. • The mergers of ABI and MillerCoors occurred within months of each other, and both were approved much quicker than the usual merger process. -

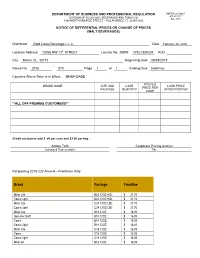

DEPARTMENT of BUSINESS and PROFESSIONAL REGULATION DBPR Form AB&T DIVISION of ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES and TOBACCO 4000A-032E Rev

DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS AND PROFESSIONAL REGULATION DBPR Form AB&T DIVISION OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES AND TOBACCO 4000A-032E Rev. 5/04 1940 NORTH MONROE STREET • TALLAHASSEE, FL 32399-1022 NOTICE OF DIFFERENTIAL PRICES OR CHANGE OF PRICES (MALT BEVERAGES) Distributor Gold Coast Beverage L.L.C. Date February 26, 2016 Location Address 10055 NW 12th STREET License No. JDBW WSL2300224 KLD City Miami, FL 33172 Beginning Date 09/28/2015 - Notice No. 2016 074 Page 1 of 1 Ending Date Indefinite Counties Where Price is in Effect: MIAMI-DADE POSTED BRAND NAME SIZE AND CASE CASH PRICE PRICE PER PACKAGE QUANTITY AFTER POSTING CASE **ALL OFF PREMISE CUSTOMERS** Credit customers add $ .40 per case and $2.00 per keg. Amber Toth Corporate Pricing Analyst Authorized Representative Title Ref posting 2015-222 Amend – Frontlines Only Brand Package Frontline Miller Lite B24 12OZ HGL $ 21.70 Coors Light B24 12OZ HGL $ 21.70 Miller Lite C24 12OZ LSE $ 21.70 Coors Light C24 12OZ LSE $ 21.70 Miller Lite B18 12OZ $ 16.05 Genuine Draft B18 12OZ $ 16.05 Coors B18 12OZ $ 16.05 Coors Light B18 12OZ $ 16.05 Miller Lite C18 12OZ $ 16.05 Coors C18 12OZ $ 16.05 Coors Light C18 12OZ $ 16.05 Miller 64 B18 12OZ $ 16.05 Miller 64 C18 12OZ $ 16.05 Lite B24 12OZ 12P $ 21.80 Genuine Draft B24 12OZ 12P $ 21.80 Coors Light B24 12OZ 12P $ 21.80 Miller Lite C24 12OZ 12P $ 21.80 Coors Light C24 12OZ 12P $ 21.80 Coors Banquet C24 12OZ 12P $ 21.80 Coors Banquet Stubby B24 12OZ 12STB $ 21.80 Coors LT Citrus Radler C24 12OZ 12P $ 21.80 Miller Lite B24 12OZ 6P $ 22.40 Coors Light B24 12OZ -

Crc - Liquor List

2701 W Howard Street Chicago, IL 60645-1303 PH: 773.465.3900 Fax: 773.465.6632 Rabbi Sholem Fishbane Kashruth Administrator Items listed as "Recommended" do not require a kosher symbol unless they are marked with a star (*) This list is updated regularly and should be considered accurate until December 31, 2013 cRc - Liquor List Bar Stock Items Bar Stock Items Bar equipment (strainers, shot measures, blenders, stir Other rods, shakers, etc.) used with non-kosher products Olives - Green should be properly cleaned and/or kashered prior to Require Certification use with kosher products. Onions - Pearl Canned or jarred require certification Recommended Coco Lopez OU* Beer Daily's OU* All unflavored beers with no additives are acceptable, OU* Holland House even without Kosher certification. This applies to both Jamaica John cRc* American and imported beers, light, dark and non- Jero OK* alcoholic beers. Mr & Mrs T OU or OK* Many breweries produce specialty brews that have Rose's - Grenadine OU* additives; please check the label and do not assume Rose's - Lime OU* that all varieties are acceptable. Furthermore, beers known to be produced at microbreweries, pub K* Tabasco - Hot Pepper Sauce breweries, or craft breweries require certification. Underberg - Herb Mix for Underberg OU* Natural Herb Bitters Recommended Other 800 - Ice Beer OU Bitters Anheuser-Busch - Redbridge Gluten Require Certification Free Coconut Milk Aspen Edge - Lager OU Requires Certification Blue Moon - Belgian White Ale OU* Cream of Coconut Blue Moon - Full Moon Winter Ale -

Camyreport-Radio Daze

RADIO DAZE: Alcohol Ads Tune in Underage Youth Executive Summary Through the years and every passing fad, advertising in 2001 and 2002 and to • Youth heard substantially less radio radio has continued to be a basic fact of conduct a case study of alcohol radio advertising for wine. Ads for wine life for youth in the United States. advertising in December 2002 and were overwhelmingly more effective- Consider this: 99.2% of teenagers January 2003 to validate the audit find- ly delivered to adults than to youth, (defined as ages 12-17) listen to radio ings. In analyzing the results of the audit showing how advertisers can target an every week—a higher percentage than and case study, the Center finds that the adult audience without overexposing for any other age group—and 80.6% lis- alcohol industry routinely overexposed youth. ten to radio every day.1 Over the course youth5 to its radio advertising by placing • Alcohol ads were placed on sta- of a week, the average teenager will listen the ads when and where youth were tions with “youth” formats. to 13.5 hours of radio.2 By comparison, more likely than adults to hear them. Seventy-three percent of the alcohol he or she will spend 10.6 hours per week radio advertising in terms of gross watching television, 7.6 hours online, In analyzing the sample from 2001- ratings points (GRPs) 7 was on four and 3.3 hours reading magazines for 2002, the Center specifically finds: formats —Rhythmic Contemporary pleasure.3 For African-American and Hit, Pop Contemporary Hit, Urban Hispanic teenagers, radio’s influence is • Youth heard more radio ads for Contemporary and Alternative— even more impressive, with average teens beer, “malternatives” and distilled that routinely have a listening audi- listening for 18.25 and 17.75 hours a spirits. -

US V. Anheuser-Busch Inbev SA/NV and Sabmiller

Case 1:16-cv-01483 Document 2-2 Filed 07/20/16 Page 1 of 38 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff, Civil Action No. v. ANHEUSER-BUSCH InBEV SA/NV, and SABMILLER plc, Defendants. PROPOSED FINAL JUDGMENT WHEREAS, Plaintiff, United States of America (“United States”) filed its Complaint on July 20, 2016, the United States and Defendants, by their respective attorneys, have consented to entry of this Final Judgment without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and without this Final Judgment constituting any evidence against or admission by any party regarding any issue of fact or law; AND WHEREAS, Defendants agree to be bound by the provisions of the Final Judgment pending its approval by the Court; AND WHEREAS, the essence of this Final Judgment is the prompt divestiture of certain rights and assets to assure that competition is not substantially lessened; AND WHEREAS, this Final Judgment requires Defendant ABI to make certain divestitures for the purpose of remedying the loss of competition alleged in the Complaint; Case 1:16-cv-01483 Document 2-2 Filed 07/20/16 Page 2 of 38 AND WHEREAS, Plaintiff requires Defendants to agree to undertake certain actions and refrain from certain conduct for the purposes of remedying the loss of competition alleged in the Complaint; AND WHEREAS, Defendants have represented to the United States that the divestitures required below can (after the Completion of the Transaction) and will be made, and that the actions and conduct restrictions can and will be undertaken, and that Defendants will later raise no claim of hardship or difficulty as grounds for asking the Court to modify any of the provisions contained below; NOW THEREFORE, before any testimony is taken, without trial or adjudication of any issue of fact or law, and upon consent of the parties, it is ORDERED, ADJUDGED, AND DECREED: I. -

2008 Great American Beer Festival Winners List

2008 Brewery and Brewer of the Year Awards: =M@R@MN±<NNJ>D<ODJI Large Brewing Company and Large Brewing Company Brewer of the Year Anheuser-Busch, Inc. Doug Muhleman GREAT Mid-Size Brewing Company and Mid-Size Brewing Company Brewer of the Year AMERICAN Sponsored by Crosby & Baker Ltd. SM Pyramid Breweries Inc. BEER Simon Pesch OCT 9•10•11 2008 COLORADO CONVENTION CENTER • DENVER, CO FESTIVAL Small Brewing Company and Small Brewing Company Brewer of the Year Sponsored by Microstar Keg Management AleSmith Brewing Co. WINNERS LIST The AleSmith Brewing Team Large Brewpub and Large Brewpub Brewer of the Year Category: 1 American-Style Cream Ale or Lager - 25 Entries Sponsored by Brewers Supply Group Gold: Lone Star, Pabst Brewing Co., Woodridge, IL Rock Bottom Brewing Silver: Hamm’s, MillerCoors, Milwaukee, WI Rock Bottom Brewing Team Bronze: Henry Weinhard’s Blue Boar Pale Ale, MillerCoors, Milwaukee, WI Small Brewpub and Small Brewpub Brewer of the Year Category: 2 American-Style Wheat Beer - 21 Entries Sponsored by Briess Malt & Ingredients Co. Gold: Pyramid Crystal Wheat Ale, Pyramid Breweries Inc., Seattle, WA Silver: Spanish Peak Crystal Weiss, Spanish Peaks Brewing Co., Stamford, CT Redwood Brewing Co. Bronze: American Wheat, Gella’s Diner and Lb. Brewing Co., Hays, KS Bill Wamby Category: 3 American-Style Hefeweizen - 52 Entries Gold: Henry Weinhard’s Hefeweizen, MillerCoors, Milwaukee, WI Silver: Hefeweizen, Widmer Brothers Brewing Co., Portland, OR Bronze: Whitetail Wheat, Montana Brewing Co., Billings, MT 2008 Michael Jackson Beer -

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert's Report In

Financial Services Guide and Independent Expert’s Report in relation to the Proposed Demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (ABN 28 050 036 372) 17 March 2011 GRANT SAMUEL & ASSOCIATES LEVEL 6 1 COLLINS STREET MELBOURNE VIC 3000 T: +61 3 9949 8800 / F: +61 3 99949 8838 www.grantsamuel.com.au Financial Services Guide Grant Samuel & Associates Pty Limited (“Grant Samuel”) holds Australian Financial Services Licence No. 240985 authorising it to provide financial product advice on securities and interests in managed investments schemes to wholesale and retail clients. The Corporations Act, 2001 requires Grant Samuel to provide this Financial Services Guide (“FSG”) in connection with its provision of an independent expert’s report (“Report”) which is included in a document (“Disclosure Document”) provided to members by the company or other entity (“Entity”) for which Grant Samuel prepares the Report. Grant Samuel does not accept instructions from retail clients. Grant Samuel provides no financial services directly to retail clients and receives no remuneration from retail clients for financial services. Grant Samuel does not provide any personal retail financial product advice to retail investors nor does it provide market-related advice to retail investors. When providing Reports, Grant Samuel’s client is the Entity to which it provides the Report. Grant Samuel receives its remuneration from the Entity. In respect of the Report in relation to the proposed demerger of Treasury Wine Estates Limited by Foster’s Group Limited (“Foster’s”) (“the Foster’s Report”), Grant Samuel will receive a fixed fee of $700,000 plus reimbursement of out-of-pocket expenses for the preparation of the Report (as stated in Section 8.3 of the Foster’s Report). -

Sabmiller and Molson Coors to Combine U.S. Operations in Joint Venture

SABMILLER AND MOLSON COORS TO COMBINE U.S. OPERATIONS IN JOINT VENTURE • Combination of complementary assets will create a stronger, more competitive U.S. brewer with an enhanced brand portfolio • Greater scale and resources will allow additional investment in brands, product innovation and sales execution • Consumers and retailers will benefit from greater choice and access to brands • Distributors will benefit from a superior core brand portfolio, simplified systems, lower operating costs and improved chain account programs • $500 million of annual cost synergies will enhance financial performance • SABMiller and Molson Coors with 50%/50% voting interest and 58%/42% economic interest 9 October 2007 (London and Denver) -- SABMiller plc (SAB.L) and Molson Coors Brewing Company (NYSE: TAP; TSX) today announced that they have signed a letter of intent to combine the U.S. and Puerto Rico operations of their respective subsidiaries, Miller and Coors, in a joint venture to create a stronger, brand-led U.S. brewer with the scale, resources and distribution platform to compete more effectively in the increasingly competitive U.S. marketplace. The new company, which will be called MillerCoors, will have annual pro forma combined beer sales of 69 million U.S. barrels (81 million hectoliters) and net revenues of approximately $6.6 billion. Pro forma combined EBITDA will be approximately $842 million1. SABMiller and Molson Coors expect the transaction to generate approximately $500 million in annual cost synergies to be delivered in full by the third full financial year of combined operations. The transaction is expected to be earnings accretive to both companies in the second full financial year of combined operations. -

Millercoors Proposed Findings of Fact

Case: 3:19-cv-00218-wmc Document #: 10 Filed: 03/28/19 Page 1 of 19 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF WISCONSIN MILLERCOORS, LLC, Plaintiff, v. Case No. 19-cv-00218 ANHEUSER-BUSCH COMPANIES, LLC, Defendant. STATEMENT OF PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFF MILLERCOORS, LLC’S MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION MillerCoors, LLC (“MillerCoors”) respectfully submits the following Statement of Proposed Findings of Fact in support of its Motion for a Preliminary Injunction. Parties 1. MillerCoors, LLC (“MillerCoors”) is a limited liability company organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware, with its principal place of business located at 250 South Wacker Drive, Suite 800, Chicago, Illinois 60606-5888. Declaration of Ryan Reis (“Reis Decl.”) ¶ 5. 2. Anheuser-Busch Companies, LLC (“AB”) is a limited liability company organized and existing under the laws of the State of Delaware, with its U.S. headquarters located in St. Louis, Missouri. Reis Decl. ¶ 13. Miller Lite and Coors Light Are Two of MillerCoors Flagship Beers 3. Frederick Miller started the Miller Brewing Company in 1855. Reis Decl. ¶ 5. 4. Adolph Coors started the Coors Brewing Company in 1873. Reis Decl. ¶ 5. DCACTIVE-48957092.7 QB\56719500.1 Case: 3:19-cv-00218-wmc Document #: 10 Filed: 03/28/19 Page 2 of 19 5. MillerCoors was created in 2008 as the U.S. joint venture between the owners of the Miller Brewing Company and the Coors Brewing Company. Reis Decl. ¶ 5. 6. Miller Lite and Coors Light were launched in the 1970s and are among the world’s first light beers. -

Generating Inclusive Growth Sabmiller Plc Sustainable Development Summary Report 2012

SABMiller plc Sustainable Development Summary Report 2012 Generating inclusive growth SABMiller plc Sustainable Development Summary Report 2012 About SABMiller plc SABMiller plc is one of the world’s largest brewers with brewing interests and distribution agreements across six continents The group’s wide portfolio includes global brands such as Pilsner Urquell, Peroni Nastro Azzurro, Miller Genuine Draft and Grolsch as well as leading local brands such as Águila, Castle, Miller Lite, Snow, Tyskie and Victoria Bitter. SABMiller is also one of the world’s largest bottlers of Coca-Cola products. In 2012 our group revenue was US$31,388 million with earnings before interest, tax, amortisation and exceptional items (EBITA) of US$5,634 million and lager volumes of 229 million hectolitres. Group revenue 2012: US$31,388m +11% 2011: US$28,311m EBITA 2012: US$5,634m +12% 2011: US$5,044m Lager volumes 2012: 229m hectolitres +5% 2011: 218m hectolitres Boundary and scope of this report This report covers the financial year ended 31 March 2012. Operations are included in this report on the basis of management control by SABMiller. Our US joint venture, MillerCoors, is also included. Our economic interest in MillerCoors is reflected when reporting quantitative key environmental performance indicators. A list of the operations covered in this report is available on page 21. Angola, Russia and Ukraine are no longer included following changes to strategic alliances this year which means that SABMiller companies no longer have management control. We aim to include new acquisitions or market entries within two years. This year SABMiller acquired Carlton and United Breweries (CUB), the Australian beverage business of Foster’s Group Limited, which will be included in the 2013 report.