Lower Mainland (#196)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater Vancouver Regional District

Greater Vancouver Regional District The Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) is a partnership of 21 municipalities and one electoral area that make up the metropolitan area of Greater Vancouver.* The first meeting of the GVRD's Board of Directors was held July 12, 1967, at a time when there were 950,000 people living in the Lower Mainland. Today, that number has doubled to more than two million residents, and is expected to grow to 2.7 million by 2021. GVRD's role in the Lower Mainland Amidst this growth, the GVRD's role is to: • deliver essential utility services like drinking water, sewage treatment, recycling and garbage disposal that are most economical and effective to provide on a regional basis • protect and enhance the quality of life in our region by managing and planning growth and development, as well as protecting air quality and green spaces. GVRD structure Because the GVRD serves as a collective voice and a decision-making body on a variety of issues, the system is structured so that each member municipality has a say in how the GVRD is run. The GVRD's Board of directors is comprised of mayors and councillors from the member municipalities, on a Representation by Population basis. GVRD departments are composed of staff and managers who are joined by a shared vision and common goals. Other GVRD entities Under the umbrella of the GVRD, there are four separate legal entities: the Greater Vancouver Water District (GVWD); the Greater Vancouver Sewerage and Drainage District (GVS&DD); the Greater Vancouver Housing Corporation (GVHC), and the Greater Vancouver Regional District. -

The Archaeology of the Dead at Boundary Bay, British Columbia

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE DEAD AT EOtDi'DhRY BAY, BRITISH COLUmLA: A fflSTORY AND CRITICAL ANALYSIS Lesley Susan it-litchefl B.A., Universiry of Alberta 1992 THESIS SUBMITTED INPARTIAL FULFILMENT OF TNE REQUIREmNTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Archaeof ogy 8 Lesley Susan Mitcheif 1996 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY June 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whofe or in part, by photocopy or nrher mas, without permission of the author. rCawi~itionsand Direstion des acquisitions et BiWiographilt; Services Branch cks serviGeS biMiographiques The author has granted an t'auteur a accorde une licence irrevocable non-exclusive licence irrbvocable et non exclusive allowing the National Library of permettant A fa Bibliotheque Canada to reproduce, taan, nationale du Canada de distribute or sell copies of reproduire, prkter, distribuer ou - his/her thesis by any means and vendre des copies de sa these in any form or format, making de quelque maniere et sous this thesis available to interested quelque forme que ce soit pour persons. mettre des exemplaires de cette thBse a la disposition des personnes intbressbes. The author refains ownership of L'auteur conserve ia propriete du I the copyright in his/her thesis. droit d'auteur qui prot6ge sa Neither the thesis nor substantial these. Ni la these ni des extraits extracts from it may be printed or substantiels de celle-ci ne otherwise reproduced without doivent &re imprimes ou his/her permission. autrement reproduits sans son - autorisation. ISBN 0-612-17019-5 f hereby grant to Simon Fraser Universi the right to lend my thesis, pro'ect or extended essay (the Me o'r which is shown below) to users of' the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. -

Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept Prepared by SNC-Lavalin Inc

West Coast Environmental Law Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept Prepared by SNC-Lavalin Inc. 31 July 2018 Document No.: 644868-1000-41EB-0001 Revision: 1 West Coast Environmental Law Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept West Coast Environmental Law Research Foundation and West Coast Environmental Law Association gratefully acknowledge the support of the funders who have made this work possible: © SNC-Lavalin Inc. 2018. All rights reserved. i West Coast Environmental Law Design Basis for the Living Dike Concept EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Background West Coast Environmental Law (WCEL) is leading an initiative to explore the implementation of a coastal flood protection system that also protects and enhances existing and future coastal and aquatic ecosystems. The purpose of this document is to summarize available experience and provide an initial technical basis to define how this objective might be realized. This “Living Dike” concept is intended as a best practice measure to meet this balanced objective in response to rising sea levels in a changing climate. It is well known that coastal wetlands and marshes provide considerable protection against storm surge and related wave effects when hurricanes or severe storms come ashore. Studies have also shown that salt marshes in front of coastal sea dikes can reduce the nearshore wave heights by as much as 40 percent. This reduction of the sea state in front of a dike reduces the required crest elevation and volumes of material in the dike, potentially lowering the total cost of a suitable dike by approximately 30 percent. In most cases, existing investigations and studies consider the relative merits of wetlands and marshes for a more or less static sea level, which may include an allowance for future sea level rise. -

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area A collaboration in support of teachers in and around Abbotsford, B.C. in celebration of National Science and Technology Week October 25, 2013 MineralsEd and Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada Led by David Huntley, PhD, GSC and David Thompson, P Geo 1 2 Fraser Valley Geotour Introduction Welcome to the Fraser Valley Geotour! Learning about our Earth, geological processes and features, and the relevance of it all to our lives is really best addressed outside of a classroom. Our entire province is the laboratory for geological studies. The landscape and rocks in the Fraser Valley record many natural Earth processes and reveal a large part of the geologic history of this part of BC – a unique part of the Canadian Cordillera. This professional development field trip for teachers looks at a selection of the bedrock and overlying surficial sediments in the Abbotsford area that evidence these geologic processes over time. The stops highlight key features that are part of the geological story - demonstrating surface processes, recording rock – forming processes, revealing the tectonic history, and evidence of glaciation. The important interplay of these phenomena and later human activity is highlighted along the way. It is designed to build your understanding of Earth Science and its relevance to our lives to support your teaching related topics in your classroom. Acknowledgments We would like to thank our partners, the individuals who led the tour to share their expertise, build interest in the natural history of the area, and inspire your teaching. -

Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford

AFFORDABLE HOUSING Choices For Families Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford The Housing Listings is a resource directory of affordable housing in British Columbia and divides the Lower Mainland into 7 zones. Zone 7 identifies affordable housing in the Fraser Valley, Abbotsford and Chilliwack. The attached listings are divided into two sections. Section #1: Apply to The Housing Registry Section 1 - Lists developments that The Housing Registry accepts applications for. These developments are either managed by BC Housing, Non-Profit societies or Co- operatives. To apply for these developments, please complete an application form which is available from any BC Housing office, or download the form from www.bchousing.org/housing- assistance/rental-housing/subsidized-housing. Section #2: Apply directly to Non-Profit Societies and Housing Co-ops Section 2 - Lists developments managed by non-profit societies or co-operatives which maintain and fill vacancies from their own applicant lists. To apply for these developments, please contact the society or co-op using the information provided under "To Apply". Please note, some non-profits and co-ops close their applicant list if they reach a maximum number of applicants. In order to increase your chances of obtaining housing it is recommended that you apply for several locations at once. Family Housing, Zone 7 - Fraser Valley, Chilliwack and Abbotsford August 2021 AFFORDABLE HOUSING SectionSection 1:1: ApplyApply toto TheThe HousingHousing RegistryRegistry forfor developmentsdevelopments inin thisthis section.section. Apply by calling 604-433-2218 or, from outside the Lower Mainland, 1-800-257-7756. You are also welcome to contact The Housing Registry by mail or in person at 101-4555 Kingsway, Burnaby, BC, V5H 4V8. -

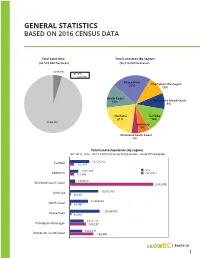

General Statistics Based on 2016 Census Data

GENERAL STATISTICS BASED ON 2016 CENSUS DATA Total Land Area Total Land Area (by region) (92,518,600 hectares) (92,518,600 hectares) 4,615,910 ALR non-ALR Peace River 22% Thompson-Okanagan 10% North Coast 13% Vancouver Island-Coast 9% Nechako Cariboo 21% 14% 87,902,700 Kootenay 6% Mainland-South Coast 4% Total Land & Population (by region) (BC total - Area - 92,518,600 (hectares) & Population - 4,648,055 (people)) Cariboo 13,128,585 156,494 5,772,130 Area Kootenay Population 151,403 3,630,331 Mainland-South Coast 2,832,000 19,202,453 Nechako 38,636 12,424,002 North Coast 55,500 20,249,862 Peace River 68,335 9,419,776 Thompson-Okanagan 546,287 8,423,161 Vancouver Island-Coast 799,400 GROW | bcaitc.ca 1 Total Land in ALR (etare by region) Total Nuber o ar (BC inal Report Number - 4,615,909 hectares) (BC total - 17,528) Cariboo 1,327,423 Cariboo 1,411 Kootenay 381,551 Kootenay 1,157 Mainland-South Coast 161,961 Mainland-South Coast 5,217 Nechako 747 Nechako 373,544 North Coast 116 North Coast 109,187 Peace River 1,335 Peace River 1,333,209 Thompson-Okanagan 4,759 Thompson-Okanagan 808,838 Vancouver Island-Coast 2,786 Vancouver Island-Coast 120,082 As the ALR has inclusions and exclusions throughout the year the total of the regional hectares does not equal the BC total as they were extracted from the ALC database at different times. Total Area o ar (etare) Total Gro ar Reeipt (illion) (BC total - 6,400,549) (BC total - 3,7294) Cariboo 1,160,536 Cariboo 1063 Kootenay 314,142 Kootenay 909 Mainland-South Coast 265,367 Mainland-South Coast 2,4352 -

Biodiversity in Greater Vancouver: Wetland Ecosystems Marshes

BIODIVERSITY IN GREATER VANCOUVER WETWET LANDLAND EECOSYSTEMCOSYSTEMS Marshes/SwaSmps Bogs and Marhes/Swamps VernBogsal P andools © Rob Rithaler Fact Sheet #1 but generally occur wherever seasonally Wetland wetted depressions occur. This important Ecosystems habitat be found throughout the Greater Vancouver Region. Threats Infilling due to development and agricultural activities. Invasive species, especially purple loosestrife. Pollution and runoff from pesticides and fertilizers. Impacts to water table infiltration from disturbance to uplands or adjacent Ministry of Sustainable Resource Management-Baseline Thematic areas. Mapping. *Data may not be complete for some areas Peat mining and removal of sphagnum for the gardening industry. What are Wetland Ecosystems? Status Wetlands are areas that are covered with water for all or part of the year. Swamps, marshes, Wetland Ecosystems are threatened, not just bogs, and vernal pools are common in the in the Greater Vancouver Region, but Greater Vancouver Region. nationally. Approximately 14% of Canada is Swamps and marshes are wet nutrient rich covered in wetlands. These unique habitat, found near streams, creeks, lakes, and ecosystems are declining rapidly. British ponds. Sedges, grasses, rushes, and reeds Columbia has a history of land conversion that characterize swamps and marshes. has led to over 80% of wetlands being drained Bogs on the other hand are nutrient poor acidic or filled for development or agricultural. wetlands dominated by peat. Bog vegetation includes low shrubs, sundews, cranberries, Nature’s Services and tree species such as shore pine. Vernal pools are temporary wetlands that are Nature’s kidneys - natural filtering wet in the spring and dry in the summer. system that helps purify water. -

The Stō:Ló Is a River of Knowledge, Halq'eméylem Is a River of Stories

Walking Backwards into the Future with Our Stories: The Stō:ló is a River of Knowledge, Halq’eméylem is a River of Stories by lolehawk Laura Buker M.A. (Education), Simon Fraser University, 1980 B.Ed., University of British Columbia, 1975 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Curriculum Theory & Implementation Program Faculty of Education © lolehawk Laura Buker Simon Fraser University Summer 2011 All rights reserved. However, in accordance with the Copyright Act of Canada, this work may be reproduced, without authorization, under the conditions for "Fair Dealing." Therefore, limited reproduction of this work for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, review and news reporting is likely to be in accordance with the law, particularly if cited appropriately. APPROVAL Name: Laura Buker Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis: Walking Backwards Into the Future With Our Stories: The St6:lo is a River of Knowledge, Haq'emeylem is a River of Stories Examining Committee: Chair: Robin Brayne, Adjunct Professor Allan MacKinnon, Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Vicki Kelly, Assistant Professor Committee Member Elizabeth Phillips, Elder, St6:lo Nation Committee Member Heesoon Bai, Associate Professor Internal/External Examiner Jan Hare, University of British Columbia External Examiner Date Defended/Approved: ii Partial Copyright Licence Abstract Storytelling is the original form of education for the indigenous families along the Fraser River. These stories have informed ecological, linguistic and cultural knowledge for thousands of years. This story begins in the time of the oldest inhabitants of the Fraser Valley along the St ó:lō where the river and the indigenous peopleevolutionary share changethe same and name: transformation Stó:lō, People that of is the personal River. -

British Columbia Coast Birdwatch the Newsletter of the BC Coastal Waterbird and Beached Bird Surveys

British Columbia Coast BirdWatch The Newsletter of the BC Coastal Waterbird and Beached Bird Surveys Volume 6 • November 2013 COASTAL WATERBIRD DATA SUPPORTS THE IMPORTANT BIRD AREA NETWORK by Krista Englund and Karen Barry Approximately 60% of British Columbia’s BCCWS data was also recently used to 84 Important Bird Areas (IBA) are located update the English Bay-Burrard Inlet and along the coast. Not surprisingly, many Fraser River Estuary IBA site summaries. BC Coastal Waterbird Survey (BCCWS) Both sites have extensive coastline areas, IN THIS ISSUE sites are located within IBAs. Through the with approximately 40 individual BCCWS • Coastal Waterbird survey, citizen scientists are contributing sites in English Bay Burrard Inlet and 22 Survey Results valuable data to help refine boundaries of in the Fraser River Estuary, although not • Beached Bird IBAs, update online site summaries (www. all sites are surveyed regularly. BCCWS Survey Results ibacanada.ca), and demonstrate that data helped demonstrate the importance • Common Loons these areas continue to support globally of English Bay-Burrard Inlet to Surf • Triangle Island significant numbers of birds. Scoters and Barrow’s Goldeneyes. In the • Forage Fish Fraser River Estuary, BCCWS data was • Tsunami Debris One recent update involved amalgamating particularly useful for demonstrating use • Real Estate three Important Bird Areas near Comox on of this IBA by globally significant numbers Foundation Project Vancouver Island into a single IBA called of Thayer’s Gull, Red-necked Grebe and • Web Resources K’omoks. BCCWS data from up to 52 survey Western Grebe. sites on Vancouver Island, Hornby and Denman Islands helped to identify areas BCCWS surveyors have made great of high bird use and provide rationale contributions to the BC Important Bird for the new boundary, which extends Areas program and we thank all past and from approximately Kitty Coleman Beach present volunteers. -

Explore Local History Through Collage: Semá:Th Xόtsa (Sumas Lake) and Sumas Prairie

Explore Local History through Collage: Semá:th Xόtsa (Sumas Lake) and Sumas Prairie Self-guided activity OVERVIEW Try your hand at an art making activity inspired by historical photographs from The Reach Gallery Museum archives1 of Semá:th Xόtsa (Sumas Lake, pronounced seMATH hOTsa) and our permanent museum exhibition Voices of the Valley.2 This Edukit uses Historical Thinking Concepts to encourage participants to use primary resources and to develop historical literacy. Both experiences use Visual Thinking Strategies to encourage participants to construct meaning based on their own observations. Figure 1. Collage example. Through this project participants will: Explore connections to identity, place, culture, and belonging through creative expression. Create works of art, collaboratively or individually using imagination, inquiry, experimentation, and purposeful play. Examine relationships between local history, the arts, and the wider world. Experience, document, and present creative works in a variety of ways. Figure 2 (above left). Semá:th Xόtsa in 1920 prior to the drainage. Catalogue no. P188, The Reach Gallery Museum archive. Figure 3 (above right). Contemporary image of Sumas Prairie. 1 For more information on The Reach Gallery Museum archives, visit https://www.thereach.ca/research-and-collections/ 2 For more information on Voices of the Valley, visit https://www.thereach.ca/exhibitions/voices-of-the-valley/ The Importance of Place and Language The Reach Gallery Museum acknowledges that the City of Abbotsford is located on S’olh Temexw. [pronounced: suh-oll TUMM ook] S’olh Temexw is the unceded, traditional, ancestral shared territory of the Semá:th First Nation and Mathekwi First Nation. These two First Nations are part of the Stό:lō Nation, the People of the River. -

News Release for IMMEDIATE RELEASE

News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Home sale and listing activity in Metro Vancouver moves off of its record-breaking pace VANCOUVER, BC – June 2, 2021 – The Metro Vancouver* housing market saw steady home sale and listing activity in May, a shift back from the record-breaking activity seen in the earlier spring months. The Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver (REBGV) reports that residential home sales in the region totalled 4,268 in May 2021, a 187.4 per cent increase from the 1,485 sales recorded in May 2020, and a 13 per cent decrease from the 4,908 homes sold in April 2021. Last month’s sales were 27.7 per cent above the 10-year May sales average. “While home sale and listing activity remained above our long-term averages in May, conditions moved back from the record-setting pace experienced throughout Metro Vancouver in March and April of this year,” Keith Stewart, REBGV economist said. “With a little less intensity in the market today than we saw earlier in the spring, home sellers need to ensure they’re working with their REALTOR® to price their homes based on current market conditions.” There were 7,125 detached, attached and apartment properties newly listed for sale on the Multiple Listing Service® (MLS®) in Metro Vancouver in May 2021. This represents a 93.4 per cent increase compared to the 3,684 homes listed in May 2020 and a 10.2 per cent decrease compared to April 2021 when 7,938 homes were listed. The total number of homes currently listed for sale on the MLS® system in Metro Vancouver is 10,970, a 10.5 per cent increase compared to May 2020 (9,927) and a 7.1 per cent increase compared to April 2021 (10,245). -

Wetland Action Plan for British Columbia

Wetland Action Plan for British Columbia IAN BARNETT Ducks Unlimited Kamloops, 954 A Laval Crescent, Kamloops, BC, V2C 5P5, Canada, email [email protected] Abstract: In the fall of 2002, the Wetland Stewardship Partnership was formed to address the need for improved conservation of wetland ecosystems (including estuaries) in British Columbia. One of the first exercises undertaken by the Wetland Stewardship Partnership was the creation of a Wetland Action Plan. The Wetland Action Plan illustrates the extent of the province's wetlands, describes their value to British Columbians, assesses threats to wetlands, evaluates current conservation initiatives, and puts forth a set of specific actions and objectives to help mitigate wetland loss or degradation. It was determined that the most significant threats to wetlands usually come from urban expansion, industrial development, and agriculture. The Wetland Stewardship Partnership then examined which actions would most likely have the greatest positive influence on wetland conservation and restoration, and listed nine primary objectives, in order of priority, in a draft ‘Framework for Action’. Next, the partnership determined that meeting the first four of these objectives could be sufficient to provide meaningful and comprehensive wetland protection, and so, committed to working together towards enacting specific recommendations in relation to these objectives. These four priority objectives are as follows: (1) Work effectively with all levels of government to promote improved guidelines and stronger legislative frameworks to support wetlands conservation; (2) Provide practical information and recommendations on methods to reduce impacts to wetlands to urban, rural, and agricultural proponents who wish to undertake a development in a wetland area; (3) Improve the development and delivery of public education and stewardship programs that encourage conservation of wetlands, especially through partnerships; and (4) Conduct a conservation risk assessment to make the most current inventory information on the status of B.C.