SIMS-MASTERS-REPORT.Pdf (772.1Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week 2 FINAL Release (2004).Qxd

Week 2 - Games of October 3 Chuck Dunlap (Primary SEC Football Contact) • [email protected] • @SEC_Chuck Southeastern Conference Communications Office Ben Beaty (Secondary Football Contact) • [email protected] • @BenBeaty SECsports.com • CollegePressBox.com Phone: (205) 458-3000 EASTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Top 10 Streak Florida 1-0 1.000 51 35 1-0 1.000 51 35 0-0 1-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 W1 Georgia 1-0 1.000 37 10 1-0 1.000 37 10 0-0 1-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 W1 Tennessee 1-0 1.000 31 27 1-0 1.000 31 27 0-0 1-0 0-0 1-0 0-0 0-0 W1 Kentucky 0-1 .000 13 29 0-1 .000 13 29 0-0 0-1 0-0 0-0 0-1 0-1 L1 Missouri 0-1 .000 19 38 0-1 .000 19 38 0-1 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-1 0-1 W1 South Carolina 0-1 .000 27 31 0-1 .000 27 31 0-1 0-0 0-0 0-1 0-1 0-0 L1 Vanderbilt 0-1 .000 12 17 0-1 .000 12 17 0-0 0-1 0-0 0-0 0-1 0-1 L1 WESTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Top 10 Streak Alabama 1-0 1.000 38 19 1-0 1.000 38 19 0-0 1-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 W1 Auburn 1-0 1.000 29 13 1-0 1.000 29 13 1-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 1-0 0-0 W1 Mississippi State 1-0 1.000 44 34 1-0 1.000 44 34 0-0 1-0 0-0 1-0 1-0 1-0 W1 Texas A&M 1-0 1.000 17 12 1-0 1.000 17 12 1-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 W1 Arkansas 0-1 .000 10 37 0-1 .000 10 37 0-1 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-1 0-1 L1 LSU 0-1 .000 34 44 0-1 .000 34 44 0-1 0-0 0-0 0-1 0-0 0-0 L1 Ole Miss 0-1 .000 35 51 0-1 .000 35 51 0-1 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-1 0-1 L1 NOTES: Eight SEC teams are ranked in this week’s Top 25 polls, including three in the Top 5 and six in the Top 15. -

Week 12 Release (2016)

Week 12 - Games of Nov. 19 Chuck Dunlap (Primary SEC Football Contact) • [email protected] • @SEC_Chuck Southeastern Conference Communications Office Ben Beaty (Secondary Football Contact) • [email protected] • @BenBeaty SECsports.com • CollegePressBox.com Phone: (205) 458-3000 • Fax: (205) 458-3030 EASTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Top 10 Streak Florida 5-2 .714 180 113 7-2 .778 236 120 5-0 1-2 1-0 5-1 0-1 0-0 W1 Tennessee 3-3 .500 190 213 7-3 .700 338 269 5-1 2-1 1-0 3-1 2-2 0-2 W2 Georgia 4-4 .500 167 192 6-4 .600 226 240 2-2 3-1 1-1 3-3 2-3 1-0 W2 Kentucky 4-4 .500 185 237 5-5 .500 282 323 4-2 1-3 0-0 3-3 0-3 0-1 L2 South Carolina 3-5 .375 126 168 5-5 .500 180 211 4-2 1-3 0-0 3-3 1-2 0-1 L1 Missouri 1-5 .167 116 193 3-7 .300 312 291 3-3 0-4 0-0 1-4 0-2 0-0 W1 Vanderbilt 1-5 .167 79 111 4-6 .400 199 220 2-2 2-4 0-0 1-4 0-2 0-0 L4 WESTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Top 10 Streak #Alabama 7-0 1.000 274 106 10-0 1.000 412 122 5-0 4-0 1-0 5-0 6-0 2-0 W10 Auburn 5-2 .714 198 117 7-3 .700 320 157 5-2 2-1 0-0 4-1 2-2 0-1 L1 LSU 4-2 .667 154 86 6-3 .667 247 125 5-1 1-1 0-1 3-2 2-1 0-1 W1 Texas A&M 4-3 .571 213 188 7-3 .700 363 222 4-1 2-2 1-0 2-3 3-1 1-1 L2 Arkansas 2-4 .333 132 228 6-4 .600 288 299 5-2 1-1 0-1 1-4 3-4 1-1 L1 Ole Miss 2-4 .333 197 202 5-5 .500 354 315 4-2 1-2 0-1 1-4 2-5 1-2 W2 Mississippi State 2-4 .333 137 194 4-6 .400 281 319 3-2 1-4 0-0 1-3 1-2 1-1 L1 # - Western Division Champion vs. -

It Just Means More

IT JUST MEANS MORE. Scholars. Champions. Leaders. These are the pillars of the Southeastern Conference, and together they represent the The SEC is a place where Innovation and Leadership are vision for an 86-year-old intercollegiate athletic conference expected and pursued. However, the pursuit extends beyond that continues to experience unparalleled success. Ranging championship rings and trophies to include officiating, ad- from record-breaking accomplishments by student-athletes ministration, and other initiatives. For example, on the heels and administrators to significant growth in media, sponsor- of its football and men’s basketball collaborative replay suc- ship, and branding, the SEC continues to prove on every cess, this year the SEC became the first collegiate conference front why it is SECond to None. to introduce centralized video review in baseball. The Conference continues to deliver record financial distri- The SEC has also amplified its position relative to Branding butions to its member universities, which makes it possible and Celebration efforts. As SECU was renamed “SEC Aca- for the Conference to support scholars through and beyond demic Relations,” it heightened its focus on programs and graduation, win championships in every sponsored varsity activities designed to highlight the teaching, research and sport, and ultimately prepare young people to change the service accomplished on SEC campuses. The Conference world. also executed Year Four of the “It Just Means More” branding campaign, continuing its presence on radio, TV and online The SEC’s leadership believes strongly that intercollegiate while saturating national championship cities with digital athletic conferences have an obligation to aid in Student- outdoor exposure. -

CFPNCG FINAL Release (2004).Qxd

CFP National Championship Game Chuck Dunlap (Primary SEC Football Contact) • [email protected] • @SEC_Chuck Southeastern Conference Communications Office Ben Beaty (Secondary Football Contact) • [email protected] • @BenBeaty SECsports.com • CollegePressBox.com Phone: (205) 458-3000 EASTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Top 10 Streak #- Florida 8-2 .800 412 263 8-4 .667 478 370 4-1 3-1 1-2 6-0 1-3 1-2 L3 Georgia 7-2 .778 299 179 8-2 .800 323 200 3-0 4-1 1-1 4-1 4-2 2-2 W4 Missouri 5-5 .500 267 323 5-5 .500 267 323 4-2 1-3 0-0 3-3 1-4 0-3 L2 Kentucky 4-6 .400 217 264 5-6 .455 240 285 3-2 1-4 1-0 3-3 2-4 0-4 W2 Tennessee 3-7 .300 215 301 3-7 .300 215 301 1-4 2-3 0-0 3-3 0-5 0-4 L1 South Carolina 2-8 .200 235 360 2-8 .200 200 360 1-4 1-4 0-0 1-5 1-4 0-3 L6 Vanderbilt 0-9 .000 133 336 0-9 .000 133 336 0-5 0-4 0-0 0-5 0-3 0-2 L9 # - Eastern Division Champion WESTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Top 10 Streak %-Alabama 10-0 1.000 495 168 12-0 1.000 578 228 5-0 5-0 2-0 6-0 5-0 3-0 W12 Texas A&M 8-1 .889 285 190 9-1 .900 326 217 4-0 4-1 1-0 4-1 2-1 1-1 W8 Auburn 6-4 .600 257 237 6-5 .545 276 272 4-1 2-3 0-1 4-2 1-4 0-3 L1 Ole Miss 4-5 .444 366 363 5-5 .500 392 383 2-3 2-2 1-0 1-4 1-2 1-2 W1 Arkansas 3-7 .300 257 349 3-7 .300 257 349 2-3 1-4 0-0 2-4 1-5 0-4 L4 Mississippi State 3-7 .300 207 283 4-7 .364 235 309 2-3 1-4 1-0 1-5 2-3 1-1 W2 *LSU 5-5 .500 320 349 5-5 .500 320 349 2-2 3-3 0-0 2-4 1-2 1-2 W2 % - Western Division Champion; * - Not eligible for postseason play NOTES: The SEC is 6-2 in the postseason, with all six wins coming against Top-25 competition - the most in history for the conference. -

Tennessee Football Game #12

TENNESSEE FOOTBALL GAME #12 #FourInARow Vols Dominating Last 4 PAGE 5 6-TIME NATIONAL CHAMPS » 13 SEC CHAMPIONSHIPS » 50 BOWL GAMES » 89 ALL-AMERICANS » 45 NFL 1ST-ROUND PICKS RV/- TENNESSEE (7-4, 4-3 SEC) SCHEDULE & RECORD vs. VANDERBILT (4-7, 2-5 SEC) OVERALL RECORD: 7-4 NOV. 28, 2015 » NEYLAND STADIUM (102,455) » KNOXVILLE, TENN. » 4 P.M. » SECN SEC 4-3 NON-CONFERENCE 3-1 HOME 4-2 THE MATCHUP | #VANDYvsTENN AWAY 2-2 NEUTRAL 1-0 TENNESSEE VOLUNTEERS VANDERBILT COMMODORES THE RECORD vs THE SCHEDULE QUICK COMPARISON 32.6 (48/5) Points/Game (127/14) 14.0 DATE UT RK. OPPONENT (TV) TIME/RESULT 20.5 (25/6) Points Allowed/Game (14/5) 18.1 Sept. 5 25/25 vs. Bowling Green (SECN) W, 59-30 213.7 (26/2) Rush Yards/Game (93/11) 150.4 Sept. 12 23/23 19/17 OKLA. (ESPN) L, 24-31 (2ot) 148.8 (47/9) Rush Yards Allowed/Game (24/5) 126.1 Sept. 19 RV/RV W. CAROLINA (ESPNU) W, 55-10 199.6 (92/9) Pass Yards/Game (112/14) 168.5 Sept. 26 RV/RV at RV/RV Florida* (CBS) L, 27-28 217.9 (58/11) Pass Yards Allowed/Game (44/8) 208.7 Oct. 3 RV/RV ARKANSAS* (ESPN2) L, 20-24 413.4 (57/7) Total Offense/Game (119/13) 318.8 Oct. 10 19/16 GEORGIA* (CBS) W, 38-31 366.7 (47/7) Total Defense/Game (22/5) 334.8 Oct. 24 at 8/8 Alabama* (CBS) L, 14-19 UTSPORTS.COM (National Ranking/Conference Ranking) VUCOMMODORES.COM Oct. -

News Release

News Release FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Oct. 10, 2017 Former NBC Sports Broadcaster Headlines Community Prayer Breakfast Gettysburg, Pa. – Veteran ESPN and NBC Sports broadcaster Phil Stone will share how he took a leap of faith in his journey “From Sports to Jesus,” during the Adams County Community Prayer Breakfast at 7 a.m. on Wednesday, Nov. 15, at the Wyndham Hotel Gettysburg. The event is hosted by the Gettysburg Adams Chamber of Commerce, Adams County’s oldest and largest business organization. For 29 years, Stone sat at the window of the television sports world calling play-by-play of NFL Football and Major League Baseball for NBC Sports and for a myriad of other networks. He was the Voice of the PAC-10 for Prime Ticket Network and did play-by-play for the old Southwest Conference on Raycom Sports. He was selected to host golf and almost every Olympic sport there is for ESPN. For the longest time, the electricity of the sports arena was all Stone needed in life. He thought he had all the answers, because he had overcome his share of hurdles. He was raised in a broken home, then the same fate met his family when his wife left with his two children. Then the kids came back asking Stone to raise them, despite his jet-setting lifestyle. In 1994 he began to wonder why, with all his success, he was feeling so empty. Three of his friends started pushing for the family to attend worship, which led him to take the largest leap of faith in his life – from sports to Jesus. -

Lexus Tops List of Most-Seen Auto Advertisements

www.spotsndots.com Subscriptions: $350 per year. This publication cannot be distributed beyond the office of the actual subscriber. Need us? 888-884-2630 or [email protected] The Daily News of TV Sales Monday, June 21, 2021 Copyright 2021. LEXUS TOPS LIST OF MOST-SEEN AUTO ADVERTISEMENTS NISSAN, TOYOTA HITCH RIDE WITH NBA PLAYOFFS ADVERTISER NEWS Lexus is No.1 in iSpot.tv’s latest ranking of the most-viewed Amazon.com’s share of the online retail market will reach automotive commercials – the ads that have generated the 41.4% by the end of 2021, according to a projection by eMar- most impressions across national broadcast and cable TV keter. The retail and technology giant’s share will represent airings, WardsAuto reports. more than the combined business done by Walmart, eBay, The first-place ad for the week of June 7 features theLexus Apple, Home Depot, Target, Best Buy, Kroger, Costco and RX. The ad scored well for its “cinematic” aspects, according Wayfair. Amazon will hold its annual Prime Day sales event to Ace Metrix Creative Assessment survey data from iSpot. this week… Walmart has made an investment in DroneUp Since May 1, the Lexus spot earned 7% higher attention after conducting a pilot program last year with the company and was 6.2% more likeable than the norm for auto brands. to air deliver COVID-19 test kits. “The trial demonstrated we Subaru’s pet adoption-themed ad appears in the ranking could offer customers delivery in minutes versus hours. Now, for the second straight week (this time at No. -

MEDIA INFORMATION Media Information

MEDIA INFORMATION Media Information Cavaliers guard Collin Sexton talks to a reporter following a 115-112 overtime win in Detroit on January 9, 2020. Fred Mcleod TV Studio & Fred McLeod TV Studio & Media Workroom Media Workroom The Cavaliers organization named the combined television studio and media workroom space at Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse the “Fred McLeod TV Studio & Media Workroom” on September 18, 2019 in honor of the team’s beloved 14-year play-by-play television announcer, who passed away unexpectedly on September 9, 2019. Given the indelible impact and legacy of Fred McLeod, and how he touched so many across the media and fan community, as well as the team he loved, the Fred McLeod TV Studio & Media Workroom serves as a lasting tribute to someone that was universally admired, respected and appreciated as a fellow media member and willing mentor to a countless number across the industry. Before and after every Cavaliers home game, home and visiting team media members gather in the television studio and media workroom space on the event level of Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse to hear from, and interview, the Cavaliers head coach. The space is also used for many other media events and reporting elements throughout the year by attending media covering games and events for newspapers, magazines, television, radio, websites and other digital platforms, as they write and file their respective stories and coverage inside the walls of this important area. A Strongsville, Ohio native, Fred served as the television voice of the Cavs since joining the team and FOX Sports Ohio in 2006. -

Acc/School Information

ACC/SCHOOL INFORMATION SHIPPING/MAILING 4512 Weybridge Lane Greensboro, NC 27407 Phone: 336-854-8787 EMAIL All staff member email address: (first initial and last [email protected]) Exceptions: Andy Fledderjohann ([email protected]) TC Gammons ([email protected]) FAX NUMBERS Administrative/Communications/Football.... 336-854-8797 Championships (Olympic Sports) .................. 336-369-1203 Compliance/Student-Athlete Welfare ............ 336-369-0065 Finance/Administration .................................. 336-316-6097 Office of the Commissioner ........................... 336-547-6268 theACC.com TWITTER: @theACC FACEBOOK: facebook.com/theACC INSTAGRAM/SNAPCHAT: @ACCsports BOSTON COLLEGE NC STATE BCEagles.com GoPack.com Twitter: @BCEagles Twitter: @PackAthletics CLEMSON NOTRE DAME ClemsonTigers.com und.com Twitter: @ClemsonTigers Twitter: @FightingIrish DUKE PITT GoDuke.com PittsburghPanthers.com Twitter: @DukeATHLETICS Twitter: @Pitt_ATHLETICS FLORIDA STATE SYRACUSE Seminoles.com Cuse.com Twitter: @Seminoles Twitter: @Cuse GEORGIA TECH VIRGINIA RamblinWreck.com VirginiaSports.com Twitter: @GTAthletics Twitter: @VirginiaSports LOUISVILLE VIRGINIA TECH GoCards.com HokieSports.com Twitter: @GoCards Twitter: @hokiesports MIAMI WAKE FOREST HurricaneSports.com GoDeacs.com Twitter: @MiamiHurricanes Twitter: @DemonDeacons NORTH CAROLINA GoHeels.com Twitter: @GoHeels 2019-20 Atlantic Coast Conference Officers President: Joe Tront, Virginia Tech Vice-President: Peter Brubaker, Wake Forest Secretary-Treasurer: Tricia Bellia, Notre Dame 2019-20 -

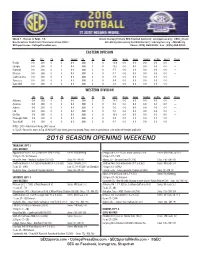

2016) FINAL Release (2004

Week 1 - Games of Sept. 1-5 Chuck Dunlap (Primary SEC Football Contact) • [email protected] • @SEC_Chuck Southeastern Conference Communications Office Ben Beaty (Secondary Football Contact) • [email protected] • @BenBeaty SECsports.com • CollegePressBox.com Phone: (205) 458-3000 • Fax: (205) 458-3030 EASTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA 2015 Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Streak Florida 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 10-4 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Georgia 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 10-3 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Kentucky 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 5-7 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Missouri 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 5-7 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- South Carolina 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 3-9 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Tennessee 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 9-4 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Vanderbilt 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 4-8 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- WESTERN DIVISION SEC Pct. PF PA Overall Pct. PF PA 2015 Home Away Neutral vs. Div. Top 25 Streak Alabama 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 14-1 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Arkansas 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 8-5 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Auburn 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 7-6 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- LSU 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 9-3 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Ole Miss 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 10-3 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Mississippi State 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 9-4 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- Texas A&M 0-0 .000 0 0 0-0 .000 0 0 8-5 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 0-0 --- NOTES: 2015 - Final record during 2015 season vs. -

Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs

Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs Prepared by: Robert Gessner President Massillon Cable TV, Inc. Massillon, OH Phone: 330-833-5509 Email: [email protected] November 5, 2013 1 Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs It is important to note that all of this information is specific to MCTV. Our costs are unique to the extent that we offer our customers a set of networks and channels that differs from others. We also may have different costs for program content due to different outcomes of negotiations. However, I am confident you will find that the facts presented are an accurate representation of the current costs of Basic Cable TV programming, the increase in costs expected in 2014 and the rest of this decade for any independent cable TV company in the US. I believe any other cable TV company will report similar increases in cost, contract terms and conditions, and expectations for the future. 2 Analysis of Changes in Basic Cable TV Programming Costs Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 4 Expect Large Increases ............................................................................................... 4 There Are No “Local” TV Stations in NE Ohio ............................................................. 4 Seven Major Media Companies Control US TV ........................................................... 4 Contracts Are Becoming More Restrictive .................................................................. -

Details of ESPN and ACC Exclusive 12Year Agreement

Details of ESPN and ACC Exclusive 12Year Agreement ESPN has been televising ACC content since the first year of the network in 197980. Highlights of the new agreement include: • Football on national TV: Regularseason action on Saturday afternoon and nights, primetime Thursdays, Labor Day Monday and the ACC Football Championship Game; • Men’s basketball on national TV: The most games ever across the ESPN networks, highlighted by both regularseason matchups of the storied DukeNorth Carolina rivalry each year; for the first time, full national telecasts on all games televised on an ESPN platform (had been local market blackouts on handful of telecasts); a new weekly Sunday franchise on ESPNU; every regularseason intraconference game and the entire conference tournament produced and distributed via ESPN and Raycom Sports; • Women’s basketball: A record number of women’s regularseason basketball games and the addition of the entire conference tournament; • Olympic sports: An expanded commitment to the league’s 22sponsored Olympic sports with regularseason and championship telecasts, highlighted by baseball, softball, lacrosse, and men’s and women’s soccer; • Syndication: Syndication rights for ACC football, basketball and Olympic sports action for overtheair and regional cable network distribution in ACC markets and beyond via an agreement with Raycom Sports and through potential sublicense agreements with other national outlets; • Digital media: Exclusive ACC football, men’s and women’s basketball, and Olympic sports games as well as simulcasts on ESPN3.com. Live ACC games, including football and basketball, on ESPN Mobile TV; • ESPN 3D: Live ACC action on ESPN 3D, ESPN’s newest network and the first 3D network to launch in the industry; • Additional outlets: ACC action on ESPN International, ESPN GamePlan, ESPN FULL COURT, ESPN Classic and ESPN Deportes; and extensive content rights for ESPN.com.