Kaiser Guibert of Nogent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communes-Aisne-IDE.Pdf

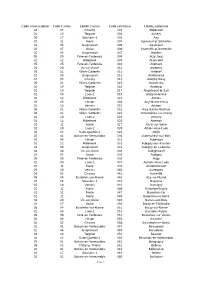

Commune Arrondissement Canton Nom et Prénom du Maire Téléphone mairie Fax mairie Population Adresse messagerie Abbécourt Laon Chauny PARIS René 03.23.38.04.86 - 536 [email protected] Achery Laon La Fère DEMOULIN Georges 03.23.56.80.15 03.23.56.24.01 608 [email protected] Acy Soissons Braine PENASSE Bertrand 03.23.72.42.42 03.23.72.40.76 989 [email protected] Agnicourt-et-Séchelles Laon Marle LETURQUE Patrice 03.23.21.36.26 03.23.21.36.26 205 [email protected] Aguilcourt Laon Neufchâtel sur Aisne PREVOT Gérard 03.23.79.74.14 03.23.79.74.14 371 [email protected] Aisonville-et-Bernoville Vervins Guise VIOLETTE Alain 03.23.66.10.30 03.23.66.10.30 283 [email protected] Aizelles Laon Craonne MERLO Jean-Marie 03.23.22.49.32 03.23.22.49.32 113 [email protected] Aizy-Jouy Soissons Vailly sur Aisne DE WULF Eric 03.23.54.66.17 - 301 [email protected] Alaincourt Saint-Quentin Moy de l Aisne ANTHONY Stephan 03.23.07.76.04 03.23.07.99.46 511 [email protected] Allemant Soissons Vailly sur Aisne HENNEVEUX Marc 03.23.80.79.92 03.23.80.79.92 178 [email protected] Ambleny Soissons Vic sur Aisne PERUT Christian 03.23.74.20.19 03.23.74.71.35 1135 [email protected] Ambrief Soissons Oulchy le Château BERTIN Nicolas - - 63 [email protected] Amifontaine Laon Neufchâtel sur Aisne SERIN Denis 03.23.22.61.74 - 416 [email protected] Amigny-Rouy Laon Chauny DIDIER André 03.23.52.14.30 03.23.38.18.17 739 [email protected] Ancienville Soissons -

Download Download

Of Palaces, Hunts, and Pork Roast: Deciphering the Last Chapters of the Capitulary of Quierzy (a. 877) Martin Gravel Politics depends on personal contacts.1 This is true in today’s world, and it was certainly true in early medieval states. Even in the Carolingian empire, the larg- est Western polity of the period, power depended on relations built on personal contacts.2 In an effort to nurture such necessary relationships, the sovereign moved with his court, within a network of important political “communication centres”;3 in the ninth century, the foremost among these were his palaces, along with certain cities and religious sanctuaries. And thus, in contemporaneous sources, the Latin term palatium often designates not merely a royal residence but the king’s entourage, through a metonymic displacement that shows the importance of palatial grounds in * I would like to thank my fellow panelists at the International Medieval Congress (Leeds, 2011): Stuart Airlie, Alexandra Beauchamp, and Aurélien Le Coq, as well as our session organizer Jens Schneider. This paper has greatly benefited from the good counsel of Jennifer R. Davis, Eduard Frunzeanu, Alban Gautier, Maxime L’Héritier, and Jonathan Wild. I am also indebted to Eric J. Goldberg, who was kind enough to read my draft and share insightful remarks. In the final stage, the precise reading by Florilegium’s anonymous referees has greatly improved this paper. 1 In this paper, the term politics will be used in accordance with Baker’s definition, as rephrased by Stofferahn: “politics, broadly construed, is the activity through which individuals and groups in any society articulate, negotiate, implement, and enforce the competing claims they make upon one another”; Stofferahn, “Resonance and Discord,” 9. -

Quierzy Info *************

Sortie à la médiathèque Régulièrement notre classe se rend à la médiathèque de Chauny. Ce sont les parents qui nous emmènent là-bas. On lit des livres, on fait des jeux, On trie des ouvrages sur la forêt et on cherche du vocabulaire sur ce thème. Pour cela, on utilise les codes couleurs et les catégories de livres. QUIERZY INFO ************* Merci aux enfants pour leur participation à ce Quierzy Info et pour les petits articles qu’ils nous ont envoyés. Désormais le dernier trimestre scolaire est terminé, nos petits écoliers ont pu profiter de quelques sorties bien Bulletin municipal n° 58 distrayantes : - Le 27 mai, ils se sont rendus à st Quentin et plus précisément au musée du papillon où ils ont pu découvrir différents insectes et leur évolution. Ils ont fini la journée au parc d’Isle toujours à la découverte des insectes. - Le 9 juin, une intervenante est venue passer la journée dans la classe de Madame Dujour: Le matin il y a eu un récapitulatif sur la métamorphose de la chenille en papillon (sujet vu à la sortie de St Quentin). Ils ont ensuite appris au travers de jeux comment différencier un papillon de jour et un papillon de nuit. L'après-midi ils sont allés à la chasse aux papillons. Les petits ont pu attraper avec des filets divers insectes (libellules, araignées, papillons .....) qu'ils ont mis dans des boites transparentes pour les observer et les ont libérés par la suite. Les enfants ayant fait un élevage de papillons (ramenés de st Quentin) les ont relâchés également durant cette après-midi-là. -

Fiche De Randonnée

Lille N 2 Laonnois A 26 Balade à pied Laon A 1 A 4 microbalade ÀÀ l’ombrl’ombree N 2 Reims A 4 Durée : 0 h 45 desdes rremparempartsts PARIS Longueur : 2 km ▼ 106 m - ▲ 125 m COUCY-LE-CHÂTEAU – COUCY-LE-CHÂTEAU Balisage : jaune et vert Sur le plateau de Coucy, en éperon au-dessus du passage de la vallée Niveau : assez facile de l’Ailette à la vallée de l’Oise, se dressent les vestiges de ce qui fut la plus grande forteresse d’Europe. Ce petit circuit qui épouse le tracé Points forts : • Cœur historique des remparts offre une succession ininterrompue de points de vue de Coucy-le-Château. sur la campagne et la forêt environnantes. • Points de vue sur les vallées de l’Ailette et de l’Oise, Porte de Soissons panorama qu’en 4, ainsi et leurs versants boisés. D (office de tourisme). se restaurer : que sur Coucy-la-Ville et Descendre la côte de Sois- la forêt de St-Gobain). • Rendez-vous sur le site chemin faisant : sons sur 20 m (panorama internet pour accéder aux 4 Tourner à gauche vers sur la vallée de l'Ailette). offres associées à ce circuit. la Porte de Chauny. Pren- • Sur la commune de Coucy- Variante de D à 1 : face à Se loger dre à droite et descendre le-Château : ville fortifiée (rempart, château), église St-Sauveur (XII-XIIIe s.), l’office de tourisme, s'engager dans l'im- sur 100 m. À hauteur du troisième candé- gloriette (XVIIe s.), source couverte, passe St-Sauveur. -

Cc La Belle Judith 31

- 95 - Une reine du IXe siècle cc La belle Judith 31 Judith (< La Belle )> est la deuxikme épouse du roi Louis le Pieux, elle est la m6re du roi (Charles le Chauve. Née un peu apres 800, elle meurt en l’année 843. Pour évoquer la figure de cette reine, qui séjourna souvent A Laon, à Samoussy, à Quierzy, à Corbeny, à Ercry (St-Erme), à Trosly-Loire, à Savonnières, à Servais ou à Versigny, - laissons parler deux auteurs, ses contemporains. Ge premier est Sun poète : Ermold le Noir, connu polrr son long <( Pohe sur le roi Louis le Pieux >. Erincld est aquitain : son teint basané, ses cheveux noirs l’ont fait surnommer : <( Nigellus >) le Noir. Intimemient lie d’amitié avec Pépin, prince d’Aquitaine et deuxième fils de Louis le Pieux et de la reine Hermengarde, première femmfe du roi, Ermold est un homme d‘&lise qui a‘toujours vécu à la cotir des Carolingiens. C’est un courtisan qui s’est imprudemment mélé aux différends qui séparent le roi Louis, d*2 ses fils du premifer lit. Ayant intrigué pom Pépin, prince d’Aquitaine, Ermold est brusquement !exilé A Strasbourg en 826. Là, pour fléchir le courroux de son souverain, Ermold adresse à Louis un grand poème en quatre chants, où il implore son pardon, tout en cklébrant la gloire de l’empereur et de sa deuxième écouse Judith. Au cours de 2.650 vers, l’exilé évoque !e paradis perdu de la cour carolin- gienne ; ce paradis, qu’il pleure en exil, est, sous sa plume, un monde de beauté et de luxe, où évolue Jgditht la Belle, qu’il dbcrit avec mille prkcieux détails vécus. -

Revolt and the Manipulation of Sacral and Private Space in 12Th-Century Laon and Bruges

Power and culture : new perspectives on spatiality in european history / edited by Pieter François, Taina Syrjämaa, Henri Terho. - Pisa : Plus-Pisa university press, 2008. – (The- matic work group. 1, Power and culture ; 3) 110 (21.) 1. Spazio – Concetto 2. Europa – Cultura - Storia I. François, Pieter II. Syrjämaa, Taina III. Terho, Henri CIP a cura del Sistema bibliotecario dell’Università di Pisa This volume is published thanks to the support of the Directorate General for Research of the European Commission, by the Sixth Framework Network of Excellence CLIOHRES.net under the contract CIT3-CT-2005-006164. The volume is solely the responsibility of the Network and the authors; the European Community cannot be held responsible for its contents or for any use which may be made of it. Cover: Alberto Papafava, View of Piazza di Siena in Roma, watercolour, Palazzo Papafava, Padua. © 1990 Photo Scala, Florence © 2008 by CLIOHRES.net The materials published as part of the CLIOHRES Project are the property of the CLIOHRES.net Consortium. They are available for study and use, provided that the source is clearly acknowledged. [email protected] - www.cliohres.net Published by Edizioni Plus – Pisa University Press Lungarno Pacinotti, 43 56126 Pisa Tel. 050 2212056 – Fax 050 2212945 [email protected] www.edizioniplus.it - Section “Biblioteca” Member of ISBN: 978-88-8492-553-4 Linguistic Revision Rodney Dean Informatic Editing Răzvan Adrian Marinescu Revolt and the Manipulation of Sacral and Private Space in 12th-Century Laon and Bruges Jeroen Deploige Ghent University ABSTRACT Thanks to the highly original testimony of the Benedictine abbot Guibert of Nogent and the cleric Galbert of Bruges we are well informed about the communal revolt in Laon in 1112, where bishop Gaudry was killed, and on the brutal events in Flanders after the murder of count Charles the Good in the church of St Donatian in Bruges in 1127. -

Déchets Ménagers Sur L’Ensemble Du Terri- Toire De La Communauté D’Agglomération

Journal d’information Novembre 2018 Ensemble e des d modernisons g é ssa che a ts am p r .3 e L la gestion des déc déchets aux hète s rie cè s c p a . ’ 4 L ménagers combran en ts es p. L 9 ourcerie ss s p e .1 R 0 teurs de T a ri im p . n 1 A 0 CE QUI CHANGE EN 2019 www.ctlf.fr Bernard Bronchain Dominique Ignaszak Président de la Communauté Vice-président en charge de la collecte et traite- d’Agglomération Chauny-Tergnier-la Fère ment des déchets des ménages et assimilés de la Communauté d’Agglomération Chauny-Tergnier-la Fère La Communauté d’Agglomération Chauny-Ter- domaine en renforçant le potentiel de collecte et gnier-La Fère a été créée le 1er janvier 2017 par la de tri des déchets tout en assurant les meilleures fusion de la communauté de communes des Villes conditions de confort et de sécurité possible pour d’Oyse et de la communauté de communes Chau- les usagers. ny-Tergnier avec intégration de trois communes de l’ancienne communauté de communes du Val de l’Ai- Convaincus que vous adhérez aux enjeux humains lette : Manicamp, Quierzy et Bichancourt. (amélioration des conditions de travail et de sécuri- té des personnels de collecte), financiers (maîtrise Les règles de collecte et de gestion des déchets des coûts) et environnementaux (réduction des gaz des 3 entités étaient différentes. Nous avons donc à effet de serre, augmentation du taux de recyclage engagé un travail très important d’harmonisation du des emballages par une amélioration du geste de tri, service dans le but de le moderniser et de répondre baisse du refus de tri), de la gestion des déchets, la aux enjeux environnementaux d’aujourd’hui. -

Contemplating Money and Wealth in Monastic Writing C. 1060–C. 1160 Giles E

© Copyrighted Material Chapter 3 Contemplating Money and Wealth in Monastic Writing c. 1060–c. 1160 Giles E. M. Gasper ashgate.com It is possible to spend money in such a way that it increases; it is an investment which grows, and pouring it out only brings in more. The very sight ofashgate.com sumptuous and exquisite baubles is sufficient to inspire men to make offerings, though not to say their prayers. In this way, riches attract riches, and money produces more money. For some unknown reasons, the richer a place appears, the more freely do offerings pour in. Gold-cased relics catch the gaze and open the purses. If you ashgate.com show someone a beautiful picture of a saint, he comes to the conclusion that the saint is as holy as the picture is brightly coloured. When people rush up to kiss them, they are asked to donate. Beauty they admire, but they do no reverence to holiness. … Oh, vanity of vanities, whose vanity is rivalled only by its insanity! The walls of the church are aglow, but the ashgate.compoor of the church go hungry. The 1 stones of the church are covered with gold, while its children are left naked. The famousApologia of Bernard of Clairvaux to Abbot William of St Thierry on the alleged decadence of the Cluniac monastic observance is well known. While Bernard does not makes an unequivocalashgate.com condemnation of wealth, adornment and money, but rather a series of qualified, if biting, remarks on the subject directed particularly to monastic communities, material prosperity and its 1 Bernard of Clairvaux,ashgate.com An Apologia to Abbot William, M. -

RN2 – Secteur De Crouy Aménagement De Sécurité De La Côte De La Perrière Du 4 Mai Au 24 Juin 2020

MINISTÈRE DE LA TRANSITION ÉCOLOGIQUE ET SOLIDAIRE Direction interdépartementale des routes Nord Lille, le 30 avril 2020 COMMUNIQUÉ DE PRESSE RN2 – secteur de Crouy Aménagement de sécurité de la côte de la Perrière du 4 mai au 24 juin 2020 Dans le cadre de son programme d’entretien du réseau et d’aménagement d’un secteur routier sensible, la Direction Interdépartementale des Routes Nord (DIRN) réalisera des travaux sur la RN2 au niveau et à l’approche du carrefour de la Perrière (Crouy). Ce chantier retardé en raison de la crise sanitaire se déroulera du lundi 4 mai au mercredi 24 juin 2020 et respectera les nouvelles précautions sanitaires. Les travaux se dérouleront en 6 phases distinctes avec pour chacune des restrictions de circulation impactant les deux sens. Phase 1 - du lundi 4 au mercredi 6 mai (jeudi 7 en fonction des aléas météorologiques) Durant cette période, la chaussée sera rénovée dans les deux sens sur une section de 600m comprise entre l’échangeur de Margival/Vregny et le carrefour de la Perrière. En journée, de 6h à 21h, la circulation sera réduite à une voie par sens et alternée sur une section d’environ 1km. De nuit, de 21h à 6h, la circulation sera rétablie à une voie par sens sur chaussée rabotée et la vitesse sera limitée à 50km/h. Phase 2 - du lundi 11 au mercredi 27 mai de jour comme de nuit La zone de travaux se situera dans le sens Soissons → Laon sur 600m débutant au niveau de la sortie vers Crouy et se terminant après le carrefour. -

Code Circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code Commune

Code circonscription Code Canton Libellé Canton Code commune Libellé_commune 04 03 Chauny 001 Abbécourt 01 18 Tergnier 002 Achery 05 17 Soissons-2 003 Acy 03 11 Marle 004 Agnicourt-et-Séchelles 01 06 Guignicourt 005 Aguilcourt 03 07 Guise 006 Aisonville-et-Bernoville 01 06 Guignicourt 007 Aizelles 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 008 Aizy-Jouy 02 12 Ribemont 009 Alaincourt 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 010 Allemant 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 011 Ambleny 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 012 Ambrief 01 06 Guignicourt 013 Amifontaine 04 03 Chauny 014 Amigny-Rouy 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 015 Ancienville 01 18 Tergnier 016 Andelain 01 18 Tergnier 017 Anguilcourt-le-Sart 01 09 Laon-1 018 Anizy-le-Grand 02 12 Ribemont 019 Annois 03 08 Hirson 020 Any-Martin-Rieux 01 19 Vervins 021 Archon 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 022 Arcy-Sainte-Restitue 05 21 Villers-Cotterêts 023 Armentières-sur-Ourcq 01 10 Laon-2 024 Arrancy 02 12 Ribemont 025 Artemps 01 11 Marle 027 Assis-sur-Serre 01 10 Laon-2 028 Athies-sous-Laon 02 13 Saint-Quentin-1 029 Attilly 02 01 Bohain-en-Vermandois 030 Aubencheul-aux-Bois 03 08 Hirson 031 Aubenton 02 12 Ribemont 032 Aubigny-aux-Kaisnes 01 06 Guignicourt 033 Aubigny-en-Laonnois 04 20 Vic-sur-Aisne 034 Audignicourt 03 07 Guise 035 Audigny 05 05 Fère-en-Tardenois 036 Augy 01 09 Laon-1 037 Aulnois-sous-Laon 03 11 Marle 039 Autremencourt 03 19 Vervins 040 Autreppes 04 03 Chauny 041 Autreville 05 04 Essômes-sur-Marne 042 Azy-sur-Marne 04 16 Soissons-1 043 Bagneux 03 19 Vervins 044 Bancigny 01 11 Marle 046 Barenton-Bugny 01 11 Marle 047 Barenton-Cel 01 11 Marle 048 Barenton-sur-Serre -

Women in the First Crusade and the Kingdom of Jerusalem

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Spring 2019 Women in the First Crusade and the Kingdom of Jerusalem Maria Carriere Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Carriere, Maria, "Women in the First Crusade and the Kingdom of Jerusalem" (2019). WWU Honors Program Senior Projects. 120. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/120 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Women in the First Crusade and the Kingdom of Jerusalem Maria Carriere 2 Women’s participation in the crusades has been attributed mainly to ambiguity in Pope Urban II’s preaching and framing of the First Crusade as a kind of pilgrimage rather than a military excursion. A comparison between ranks of women during the People’s Crusade and the First Crusade has been lacking in the historiography of these crusade expeditions. By analyzing attitudes and perceptions toward women, we can connect women’s ability to participate in crusading to their economic status. A comparison between chroniclers and contemporaries’ attitudes toward and descriptions of women in the People’s and the First Crusades can provide insight into women’s economic status, religious affiliation, and actions and how these factors influenced the crusades themselves. -

The Royal Abbey of Saint Médard in Soissons

Join us in helping to carry on 1500 years of history The Royal Abbey I would like to contribute to the mission of the ARSMS, including the preservation of the Royal Association for the Royal Abbey of Saint Abbey of Saint Médard in Soissons, a registered Médard in Soissons (ARSMS) of Saint Médard historical monument. Created in 2016, ARSMS’s mission includes the in Soissons q I wish to become a member of the ARSMS for preservation and protection of the site, as well an annual fee of 10 euros. as public outreach and international scientific investigation aimed at deepening understanding of q I wish to make a donation to the ARSMS. the very significant spiritual, political, and economic roles the Abbey played in the history of medieval Name ___________________________________ France, especially during the Merovingian and Carolingian periods. Address _________________________________ Contact: [email protected] ________________________________________ Mailing address: 10 rue des Longues Raies, E-mail __________________________________ 02200 Soissons Telephone _______________________________ Website: www.saint-medard-soissons.fr Date and signature ________________________ At the present time, all site visits must be Payment methods: personal check or money arranged by appointment with the Tourist Office in Soissons, or with ARSMS. order made out to “Association Abbaye Royale 1500 Years of History Saint-Médard de Soissons.” Please include this form, signed and dated, and mail to: ARSMS, 10, rue des Longues Raies, 02200 Soissons. Historical Background Thank you for your support! Founded in 560 to house the relics of Saint Médard, bishop of Noyon, this Benedictine Abbey soon became q For tax purposes, I wish to receive a receipt for one of the principal spiritual and political centers of all gifts exceeding 10 euros.