Louise Mackenzie Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

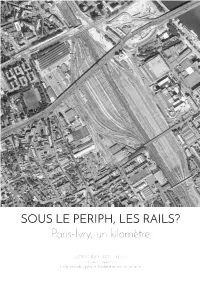

SOUS LE PERIPH, LES RAILS? Paris-Ivry, Un Kilomètre

SOUS LE PERIPH, LES RAILS? Paris-Ivry, un kilomètre WORKSHOP EUROPEEN N°4 du 17 au 24 février 2017 Ecole nationale supérieure d’architecture Paris-Val de Seine 240 étudiants de Master 1 soit 6 groupes d’environ 40 étudiants inscrits dans tous les domaines d’études partic- ipent au Workshop. Chaque groupe est encadré par un des architectes-enseignants invités. 240 students in first year of master therefore six groups of 40 students studying in all fields of study. Each group is working with a specific invited architect - teacher. Workshop européen n° 4 du 17 février au 24 février 2017 SOUS LE PÉRIPH, LES RAILS? Paris-Ivry, un kilomètre Architectes- enseignants invités Guest architects - teachers Aljosa DEKLEVA Gulia MARINO (Ljubljana, Slovénie) (Lausanne, Suisse) Frédéric FLOQUET Olivier RAFFAELLI (Valence, Espagne) (Sao Paulo, Brésil, Paris) Richard MANAHL Jonathan WOODROFFE (Vienne, Autriche) (Londres, Angleterre) Groupe de pilotage enseignant Teacher Team Marie-Hélène Badia Dragoslav Mirkovic Cyrille Faivre Dominique Pinon (coordinateur) Brigit de Kosmi Nathalie Regnier-Kagan Sylvia Lacaisse Donato Severo Pierre Léger Marco Tabet Michel Lévi Ludovic Vion Moniteurs étudiants en binôme Student instructors Armelle Breuil Flora-Lou Leclair Colombe Crouan Sophie Loyer Thomas Gabriel Fares Makhlouf Théo Gruss- Koskas Julie Ondo Lucile Ink Florent Paoli Victor Le Forestier Philippe Robart 3 SOMMAIRE SUMMARY 01 Organisation de la semaine 7 Week Organization 02 Objectifs pédagogiques 11 Educational goals 03 Présentation des architectes invités -

The Stepford Wives Free

FREE THE STEPFORD WIVES PDF Ira Levin,Chuck Palanhiuk | 160 pages | 21 Jul 2011 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9781849015899 | English | London, United Kingdom The Stepford Wives - Wikipedia Netflix uses cookies for personalization, to customize its online advertisements, and for other The Stepford Wives. Learn more The Stepford Wives change your cookie preferences. Netflix supports the Digital Advertising Alliance principles. By interacting with this site, you agree to our use of cookies. We use cookies why? You can change cookie preferences ; continued site use signifies consent. Contact us. Netflix Netflix. After moving to the beautiful suburb of Stepford with her husband, a woman begins to suspect something is radically wrong with the neighborhood wives. Watch all you want for free. Nicole Kidman and Matthew Broderick are new to a very strange neighborhood in this comedic remake. More Details. Watch offline. Available to download. This movie is Coming Soon. The Witcher: Blood Origin. In an elven world 1, years before Geralt of Rivia, the worlds of monsters, men and elves merge to become one — and the very first Witcher arises. In s Amsterdam, a family starts the first-ever phone sex line — but being in the business of sexual desires The Stepford Wives them to question their own. For employees of the Deep State, conspiracies aren't just theories — they're fact. And keeping them a secret is a full-time job. A The Stepford Wives known as the maverick of news media defiantly chases the truth in this series adaptation of the hit movie of the same name. A journalist investigates The Stepford Wives case of Anna Delvey, the Instagram-legendary heiress who stole the hearts -- and money -- of New York's social elite. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

1 Evolving Authorship, Developing Contexts: 'Life Lessons'

Notes 1 Evolving Authorship, Developing Contexts: ‘Life Lessons’ 1. This trajectory finds its seminal outlining in Caughie (1981a), being variously replicated in, for example, Lapsley and Westlake (1988: 105–28), Stoddart (1995), Crofts (1998), Gerstner (2003), Staiger (2003) and Wexman (2003). 2. Compare the oft-quoted words of Sarris: ‘The art of the cinema … is not so much what as how …. Auteur criticism is a reaction against sociological criticism that enthroned the what against the how …. The whole point of a meaningful style is that it unifies the what and the how into a personal state- ment’ (1968: 36). 3. For a fuller discussion of the conception of film authorship here described, see Grist (2000: 1–9). 4. While for this book New Hollywood Cinema properly refers only to this phase of filmmaking, the term has been used by some to designate ‘either something diametrically opposed to’ such filmmaking, ‘or some- thing inclusive of but much larger than it’ (Smith, M. 1998: 11). For the most influential alternative position regarding what he calls ‘the New Hollywood’, see Schatz (1993). For further discussion of the debates sur- rounding New Hollywood Cinema, see Kramer (1998), King (2002), Neale (2006) and King (2007). 5. ‘Star image’ is a concept coined by Richard Dyer in relation to film stars, but it can be extended to other filmmaking personnel. To wit: ‘A star image is made out of media texts that can be grouped together as promotion, publicity, films and commentaries/criticism’ (1979: 68). 6. See, for example, Grant (2000), or the conception of ‘post-auteurism’ out- lined and critically demonstrated in Verhoeven (2009). -

Fall 2001 Page 1 of 7

Screen/Society Fall 2001 Page 1 of 7 Screen/Society Fall 2001 Schedule Update 11/12: The Richard White Auditorium will not be 35mm-ready until after the Fall Semester. In order to accomodate 35mm, some screening dates and locations have been changed. Please check this website regularly for updates. All 35mm film programming will be held in Griffith. Screen/Society was started in 1991 by graduate students in English and the Graduate Program in Literature working with staff in the Program in Film and Video. It has continued to provide challenging programming for the Duke community, emphasizing the importance of screening work in its original format, whether video, 16mm or 35mm. Our goal is to advance the academic study of film at Duke and to work with Arts and Sciences Departments to find ways to relate film, video, and digital art to studies in other disciplines. Screen/Society encompasses the following components: z Public Exhibition ? department-, center- and program-curated film series z Southern Circuit ? touring series organized by the South Carolina Arts Commission featuring new works and the artists in person z North Carolina Latin American Film Festival ? touring series presented at state schools and universities z Cinemateque ? Arts and Sciences course-related film screenings Films will be screened at 8pm in the Richard White Auditorium on Duke University?s East Campus, unless otherwise noted. Please check schedule for screening dates. All films are free to the general public unless otherwise noted. Public Exhibition provides an opportunity for departments, programs, and centers to curate film series. These series may be related to courses, research or broad themes of interest. -

Cyborg Cinema and Contemporary Subjectivity

Cyborg Cinema and Contemporary Subjectivity Sue Short Cyborg Cinema and Contemporary Subjectivity This page intentionally left blank Cyborg Cinema and Contemporary Subjectivity Sue Short Faculty of Continuing Education Birkbeck College, University of London, UK © Sue Short 2005 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 1–4039–2178–4 hardback This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Unseen Horrors: the Unmade Films of Hammer

Unseen Horrors: The Unmade Films of Hammer Thesis submitted by Kieran Foster In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy De Montfort University, March 2019 Abstract This doctoral thesis is an industrial study of Hammer Film Productions, focusing specifically on the period of 1955-2000, and foregrounding the company’s unmade projects as primary case studies throughout. It represents a significant academic intervention by being the first sustained industry study to primarily utilise unmade projects. The study uses these projects to examine the evolving production strategies of Hammer throughout this period, and to demonstrate the methodological benefits of utilising unmade case studies in production histories. Chapter 1 introduces the study, and sets out the scope, context and structure of the work. Chapter 2 reviews the relevant literature, considering unmade films relation to studies in adaptation, screenwriting, directing and producing, as well as existing works on Hammer Films. Chapter 3 begins the chronological study of Hammer, with the company attempting to capitalise on recent successes in the mid-1950s with three ambitious projects that ultimately failed to make it into production – Milton Subotsky’s Frankenstein, the would-be television series Tales of Frankenstein and Richard Matheson’s The Night Creatures. Chapter 4 examines Hammer’s attempt to revitalise one of its most reliable franchises – Dracula, in response to declining American interest in the company. Notably, with a project entitled Kali Devil Bride of Dracula. Chapter 5 examines the unmade project Nessie, and how it demonstrates Hammer’s shift in production strategy in the late 1970s, as it moved away from a reliance on American finance and towards a more internationalised, piece-meal approach to funding. -

Paris Cinema.1.1

01 02 03 The New Wave Hotel 04 05 Roland-François Lack 06 07 08 09 The association of the French New Wave with the kind of movement through urban 10 space that has been called flânerie is a familiar one. A defamiliarising strategy in this 11 chapter, and in my research more broadly,1 is to examine and occupy the spaces in 12 which New Wave films come to rest, countering a general assumption that cinema is 13 always about movement. The hotel is a peculiarly cinematic stopping place because, it 14 has been argued, it is ‘always already in motion’, a ‘ceaseless flux of reservations, occu- 15 pations and vacancies’.2 By fixing exactly the locations of Paris hotels in New Wave films 16 and by looking closely at the contents of the rooms in those hotels, this chapter will try 17 to resist the appeal of such mobility and fix its gaze firmly on its object, unmoved. The 18 suggestion will be, finally, that the French New Wave is less a cinema of flânerie than 19 it is a cinema of stasis; is as much a cinema of interiors as it is a cinema of the street. 20 What, cinematically, is particular about the New Wave’s use of hotels? New Wave 21 hotels are places of passage, temporary stopping places that signify transience and, in 22 the end, mobility. In her study of cinematic flânerie, Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues defines 23 the cinematographic image as ‘passage’,3 and though she goes on to illustrate the point 24 through New Wave films that follow characters as they walk in streets, fixing on their 25 ‘singular mobility’, here we will be following the New Wave’s characters into spaces 26 where walking is restricted. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for over twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire.␣ Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers.␣ At the same time it originally aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire.␣ Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions.␣ Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), and Bruder Lustig, which further explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend is now added Der Heidenkönig (The Heathen King).␣ Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action. -

De Hong Sang-Soo Well-Trodden Paths and Sights of Paris: Hong Sang-Soo’S Night and Day (2008) André Habib

Document generated on 09/30/2021 7:02 p.m. Études littéraires En terrains connus ou « choses vues » dans Paris : Night and Day (2008) de Hong Sang-soo Well-trodden paths and sights of Paris: Hong Sang-soo’s Night and Day (2008) André Habib Montréal, Paris, Marseille : la ville dans la littérature et le cinéma Article abstract contemporains. Plus vite que le coeur des mortels With the possible exception of New York City, Paris is one of cinema’s most Volume 45, Number 2, Summer 2014 beloved “characters”. From the Lumière brothers to New Wave heroes, from Debord’s psychogeography to Rohmer’s emotional cartography, from the 1965 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1028980ar Six in Paris and the 1985 Japanese takes on the city to the 2006 Paris je t’aime, DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1028980ar no other city has graced film and influenced filmmakers so often as Paris. Of general interest is the evolution of that city in contemporary Asian filmography and, in particular, the 2008 Night and Day by Hong Sang-soo, the See table of contents only movie he shot outside his native South Korea. In keeping with his obsession with paring down locales (coffee shops, bars, apartments), neighbourhoods and events (drunken binges, love triangles, holidays), Night Publisher(s) and Day is restricted to a familiar take on the city’s 14th arrondissement. Focussed not so much on culture clash or encounters as on the city itself, Night Département des littératures de l’Université Laval and Day zooms in on the most trivial sights, the most ordinary settings, the drudgery of daily life and the paths trodden by the main character (who ends ISSN up meeting mostly South Koreans). -

The Films the Films

THE FRENCH NEW WAVE March 9 continued tions that were a signature of their LE BEAU SERGE (1958) Director: Claude work. Thus, their intellectual fer Chabrol. 97 minutes. With Gerald ment was translated into highly Blain, Jean-Claude Brialy, Bernadette spirited recombinations and in LaFont. troductions of new elements into the grammar of film. The first New Wave feature: a "moral" drama about a wanderer who Some of their main influences were returns to his roots to find his old American genre films, even B pic village friend a drunkard. In- tures (like Monogram Studios', fluenced by Hitchcock, Chabrol here dedicatee of Godard's BREATHLESS), displays his own style of critical with borrowings to various degrees detachment in dealing with the theme from Hitchcock, Lang, etc. These in of "exchange." The bucolic setting fluences were the staples of Bazin's would be reversed a year later in his "auteur" theory. Bazin stressed mise city mouse/country mouse {jrama THE en scene, the fabrication of a COUSINS, made with' the same leads. self-contained artistically con the escape into the House of Fiction trolled visual universe by the in CELINE AND JULIE ... , illustrates March 16 director (cf. Truffaut's DAY FOR the extremes of poetic inspiration NIGHT) as the center of creativity in and improvisation in the New Wave. THE SIGN OF THE LION (1959) Director: film. Rohmer and Chabrol, for exam Eric Rohmer. Approximately 90 ple, wrote a book on Hitchcock, as Unlike most films of their time, none minutes. did Truffaut later on, all ap of these turn into star preciating the moral dimensions of vehicles, either distanced or A simple Renoiresque story (cf.