Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

741.5 Batman..The Joker

Darwyn Cooke Timm Paul Dini OF..THE FLASH..SUPERBOY Kaley BATMAN..THE JOKER 741.5 GREEN LANTERN..AND THE JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA! MARCH 2021 - NO. 52 PLUS...KITTENPLUS...DC TV VS. ON CONAN DVD Cuoco Bruce TImm MEANWHILE Marv Wolfman Steve Englehart Marv Wolfman Englehart Wolfman Marshall Rogers. Jim Aparo Dave Cockrum Matt Wagner The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of In celebration of its eighty- queror to the Justice League plus year history, DC has of Detroit to the grim’n’gritty released a slew of compila- throwdowns of the last two tions covering their iconic decades, the Justice League characters in all their mani- has been through it. So has festations. 80 Years of the the Green Lantern, whether Fastest Man Alive focuses in the guise of Alan Scott, The company’s name was Na- on the career of that Flash Hal Jordan, Guy Gardner or the futuristic Legion of Super- tional Periodical Publications, whose 1958 debut began any of the thousands of other heroes and the contemporary but the readers knew it as DC. the Silver Age of Comics. members of the Green Lan- Teen Titans. There’s not one But it also includes stories tern Corps. Space opera, badly drawn story in this Cele- Named after its breakout title featuring his Golden Age streetwise relevance, emo- Detective Comics, DC created predecessor, whose appear- tional epics—all these and bration of 75 Years. Not many the American comics industry ance in “The Flash of Two more fill the pages of 80 villains become as iconic as when it introduced Superman Worlds” (right) initiated the Years of the Emerald Knight. -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

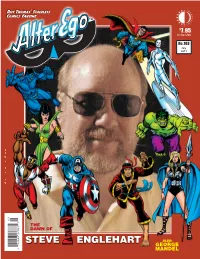

Englehart Steve

AE103Cover FINAL_AE49 Trial Cover.qxd 6/22/11 4:48 PM Page 1 BOOKS FROM TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING Roy Thomas’ Stainless Comics Fanzine $7.95 In the USA No.103 July 2011 STAN LEE UNIVERSE CARMINE INFANTINO SAL BUSCEMA MATT BAKER The ultimate repository of interviews with and PENCILER, PUBLISHER, PROVOCATEUR COMICS’ FAST & FURIOUS ARTIST THE ART OF GLAMOUR mementos about Marvel Comics’ fearless leader! Shines a light on the life and career of the artistic Explores the life and career of one of Marvel Comics’ Biography of the talented master of 1940s “Good (176-page trade paperback) $26.95 and publishing visionary of DC Comics! most recognizable and dependable artists! Girl” art, complete with color story reprints! (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 (224-page trade paperback) $26.95 (176-page trade paperback with COLOR) $26.95 (192-page hardcover with COLOR) $39.95 QUALITY COMPANION BATCAVE COMPANION EXTRAORDINARY WORKS IMAGE COMICS The first dedicated book about the Golden Age Unlocks the secrets of Batman’s Silver and Bronze OF ALAN MOORE THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE publisher that spawned the modern-day “Freedom Ages, following the Dark Knight’s progression from Definitive biography of the Watchmen writer, in a An unprecedented look at the company that sold Fighters”, Plastic Man, and the Blackhawks! 1960s camp to 1970s creature of the night! new, expanded edition! comics in the millions, and their celebrity artists! (256-page trade paperback with COLOR) $31.95 (240-page trade paperback) $26.95 (240-page trade paperback) $29.95 (280-page trade -

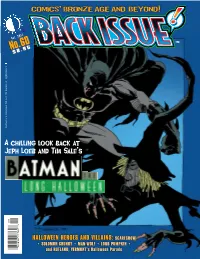

A Chilling Look Back at Jeph Loeb and Tim Sale's

Jeph Loeb Sale and Tim at A back chilling look Batman and Scarecrow TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 9 No.60 Oct. 201 2 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 COMiCs HALLOWEEN HEROES AND VILLAINS: • SOLOMON GRUNDY • MAN-WOLF • LORD PUMPKIN • and RUTLAND, VERMONT’s Halloween Parade , bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD ’ s SCARECROW i . Volume 1, Number 60 October 2012 Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! The Retro Comics Experience! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich J. Fowlks COVER ARTIST Tim Sale COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Scott Andrews Tony Isabella Frank Balkin David Anthony Kraft Mike W. Barr Josh Kushins BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 Bat-Blog Aaron Lopresti FLASHBACK: Looking Back at Batman: The Long Halloween . .3 Al Bradford Robert Menzies Tim Sale and Greg Wright recall working with Jeph Loeb on this landmark series Jarrod Buttery Dennis O’Neil INTERVIEW: It’s a Matter of Color: with Gregory Wright . .14 Dewey Cassell James Robinson The celebrated color artist (and writer and editor) discusses his interpretations of Tim Sale’s art Nicholas Connor Jerry Robinson Estate Gerry Conway Patrick Robinson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Scarecrow . .19 Bob Cosgrove Rootology The history of one of Batman’s oldest foes, with comments from Barr, Davis, Friedrich, Grant, Jonathan Crane Brian Sagar and O’Neil, plus Golden Age great Jerry Robinson in one of his last interviews Dan Danko Tim Sale FLASHBACK: Marvel Comics’ Scarecrow . .31 Alan Davis Bill Schelly Yep, there was another Scarecrow in comics—an anti-hero with a patchy career at Marvel DC Comics John Schwirian PRINCE STREET NEWS: A Visit to the (Great) Pumpkin Patch . -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

Yellow Peril!

Yellow Peril! An Archive of AntiAsian Fear Edited and Introduced by John Kuo Wei Tchen and Dylan Yeats VERSO London • New York ^^/p/a ■ The Asian/Paciflc/American InstiJutc at NYU Published in collaboration with the Asian / Pacific / American Institute, NYU First published by Verso 2014 © John Kuo Wei Tchen and Dylan Yeats 2014 In Memory ofYoshio Kishi, Him Mark Lai, and Alexander Saxton All rights reserved The moral rights o f the authors have been asserted 1 3 5 7 9 108642 Verso UK: 6 Meard Street, London W IF OEG US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201 www.versobooks.com Verso is the imprint of New Left Books ISBN13: 9781781681237 (pbk) ISBN13: 9781781681244 (hbk) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Yellow peril! : an archive of antiAsian fear / edited and introduced by John Kuo Wei Tchen and Dylan Yeats, pages cm ISBN 9781781681237 (pbk.) — ISBN 9781781681244 (hardcover) 1. Asian Americans in popular culture— History— Sources. 2. Asian Americans— History— Sources. 3. Xenophobia— United States— History— Sources. 4. Racism— United States— History— Sources. 5. United States— Race relations— Sources. I. Tchen, John Kuo Wei, editor, author. II. Yeats, Dylan, editor, author. E184.A75Y45 2014 973’.0495—dc23 2013026694 Typeset in Garamond Pro by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall Printed in Singapore by Tien Wah Press ‘"The person who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign place ” Contents Hugo of St. -

Toward an Aesthetics and Politics of Guilt in American

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Responsibility, Freedom, and the State: Toward an Aesthetics and Politics of Guilt in American Literature, 1929-1960 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature by Timothy Jeffrey Haehn 2014 © Copyright by Timothy Jeffrey Haehn 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Responsibility, Freedom, and the State: Toward an Aesthetics and Politics of Guilt in American Literature, 1929-1960 By Timothy Jeffrey Haehn Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Eleanor K. Kaufman, Chair This dissertation proposes a fundamental reassessment of guilt in twentieth-century American literature. I claim that guilt ought to be understood not so much in relation to the Holocaust or the history of U.S. race relations as in relation to the state. In readings of Mary McCarthy, Richard Wright, J. D. Salinger, Arthur Miller, and Saul Bellow, as well as the early Superman comics and fiction and criticism that invoke Fyoder Dostoevsky’s work, this project demonstrates how authors of fiction and popular culture mobilize feelings of responsibility and guilt to symbolize anxieties over the diminished role of the state as a vehicle for public relief. As the federal government jettisoned burdens that it had borne since the Depression, the writers in question depict various mechanisms employed by individuals to absorb state burdens and to compensate for the reduced availability of state-backed relief. With renewed emphasis on existential categories such as guilt, freedom, and anxiety, I trace tensions at the core of mid- twentieth-century narratives that situate them squarely within the problematics of antistatism. -

AKA Clark Kent) Middle Name Is Joseph

Superman’s (AKA Clark Kent) Middle Name Is Joseph. What’s that?! There in the sky? Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No! It’s the Man of Tomorrow! Superman has gone by many names over the years, but one thing has remained the same. He has always stood for what’s best about humanity, all of our potential for terrible destructive acts, but also our choice to not act on the level of destruction we could wreak. Superman was first created in 1933 by Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, the writer and artist respectively. His first appearance was in Action Comics #1, and that was the beginning of a long and illustrious career for the Man of Steel. In his unmistakable blue suit with red cape, and the stylized red S on his chest, the figure of Superman has become one of the most recognizable in the world. The original Superman character was a bald telepathic villain that was focused on world domination. It was like a mix of Lex Luthor and Professor X. Superman’s powers include incredible strength, the ability to fly. X-ray vision, super speed, invulnerability to most attacks, super hearing, and super breath. He is nearly unstoppable. However, Superman does have one weakness, Kryptonite. When exposed to this radioactive element from his home planet, he becomes weak and helpless. Superman’s alter ego is mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent. He lives in the city of Metropolis and works for the newspaper the Daily Planet. Clark is in love with fellow reporter Lois Lane. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse

APRIL 8 – MAY 4 Quadracci Powerhouse By David Bar Katz | Directed by Mark Clements Judy Hansen, Executive Producer Milwaukee Repertory Theater presents The History of Invulnerabilty PLAY GUIDE • Play Guide written by Lindsey Hoel-Neds Education Assistant With contributions by Margaret Bridges Education Intern • Play Guide edited by Jenny Toutant Education Director MARK’S TAKE Leda Hoffmann “I’ve been hungry to produce History for several seasons. Literary Coordinator It requires particular technical skills, and we’ve now grown our capabilities such that we can successfully execute this Lisa Fulton intriguing exploration of the life of Jerry Siegel and his Director of Marketing & creation, Superman. I am excited to build, with my wonder- Communications ful creative team, a remarkable staging of this amazing play that will equally appeal to theater-lovers and lovers of comic • books and superheroes.”” -Mark Clements, Artistic Director Graphic Design by Eric Reda TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis ....................................................................3 Biography of Jerry Siegel. .5 Biography of Superman .....................................................5 Who’s Who in the Play .......................................................6 Mark Clements The Evolution of Superman. .7 Artistic Director The Golem Legend ..........................................................8 Chad Bauman The Übermensch ............................................................8 Managing Director Featured Artists: Jef Ouwens and Leslie Vaglica ...............................9 -

“I Am the Villain of This Story!”: the Development of the Sympathetic Supervillain

“I Am The Villain of This Story!”: The Development of The Sympathetic Supervillain by Leah Rae Smith, B.A. A Thesis In English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved Dr. Wyatt Phillips Chair of the Committee Dr. Fareed Ben-Youssef Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leah Rae Smith Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to share my gratitude to Dr. Wyatt Phillips and Dr. Fareed Ben- Youssef for their tutelage and insight on this project. Without their dedication and patience, this paper would not have come to fruition. ii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………….ii ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………...iv I: INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………….1 II. “IT’S PERSONAL” (THE GOLDEN AGE)………………………………….19 III. “FUELED BY HATE” (THE SILVER AGE)………………………………31 IV. "I KNOW WHAT'S BEST" (THE BRONZE AND DARK AGES) . 42 V. "FORGIVENESS IS DIVINE" (THE MODERN AGE) …………………………………………………………………………..62 CONCLUSION ……………………………………………………………………76 BIBLIOGRAPHY …………………………………………………………………82 iii Texas Tech University, Leah Rae Smith, May 2021 ABSTRACT The superhero genre of comics began in the late 1930s, with the superhero growing to become a pop cultural icon and a multibillion-dollar industry encompassing comics, films, television, and merchandise among other media formats. Superman, Spider-Man, Wonder Woman, and their colleagues have become household names with a fanbase spanning multiple generations. However, while the genre is called “superhero”, these are not the only costume clad characters from this genre that have become a phenomenon.