The Place of Neuroanatomy in the Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuclear Expression of PG-21, SRC-1, and Pcreb in Regions of the Lumbosacral Spinal Cord Involved in Pelvic Innervation in Young Adult and Aged Rats

Original Article http://dx.doi.org/10.5115/acb.2012.45.4.241 pISSN 2093-3665 eISSN 2093-3673 Nuclear expression of PG-21, SRC-1, and pCREB in regions of the lumbosacral spinal cord involved in pelvic innervation in young adult and aged rats Richard N. Ranson1,2, Jennifer H. Connelly1, Robert M. Santer1, Alan H. D. Watson1 1Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff,2 School of Applied Sciences, Northumbria University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK Abstract: In rats, ageing results in dysfunctional patterns of micturition and diminished sexual reflexes that may reflect degenerative changes within spinal circuitry. In both sexes the dorsal lateral nucleus and the spinal nucleus of the bulbospongiosus, which lie in the L5-S1 spinal segments, contain motor neurons that innervate perineal muscles, and the external anal and urethral sphincters. Neurons in the sacral parasympathetic nucleus of these segments provide autonomic control of the bladder, cervix and penis and other lower urinary tract structures. Interneurons in the dorsal gray commissure and dorsal horn have also been implicated in lower urinary tract function. This study investigates the cellular localisation of PG-21 androgen receptors, steroid receptor co-activator one (SRC-1) and the phosphorylated form of c-AMP response element binding protein (pCREB) within these spinal nuclei. These are components of signalling pathways that mediate cellular responses to steroid hormones and neurotrophins. Nuclear expression of PG-21 androgen receptors, SRC-1 and pCREB in young and aged rats was quantified using immunohistochemistry. There was a reduction in the number of spinal neurons expressing these molecules in the aged males while in aged females, SRC-1 and pCREB expression was largely unchanged. -

Motor Tracts

Motor tracts There are two major descending tracts Pyramidal tracts (Corticospinal ) : Conscious control of skeletal muscles Extrapyramidal: Upper motor Subconscious neurons. regulation of balance, muscle tone, eye, hand, and upper limb position: Vestibulospinal tracts Lower motor neurons. Reticulospinal tracts Rubrospinal tracts Tectospinal tracts Extrapyramidal tracts arise in the brainstem, but are under the influence of the cerebral cortex Rexed laminae • Lamina 8: motor interneurons, Commissural nucleus • Lamina 9: ventral horn, LMN, divided into nuclei: Ventromedial : all segements (extensors of vertebral coloumn) Dorsomedial : (T1-L2) intercostals and abdominal muscles Ventrolateral: C5-C8 (arm) L2-S2 (thigh) Dorsolateral: C5-C8 (Forearm), L3-S3 (Leg) Reterodorsolateral: C8-T1 (Hand), S1-S2 (foot) Central: Phrenic nerve (C3-C5) • Lamina X : Surrounds the central canal – the grey commissure Motor neurons of anterior horn Medial group: (All segments) Lateral group: only enlargements Muscle spindles are sensory receptors within the belly of a muscle that primarily detect changes in the length of this muscle. Each muscle spindle consists of an encapsulated cluster of small striated muscle fibers (" intrafusal muscle fibers ") with somewhat unusual structure (e.g., nuclei may be concentrated in a cluster near the middle of the fiber's length). The skeletal muscle is composed of: Extrafusal fibers (99%): innervated by alpha motor neurons . Intrafusal fibers (1%): innervated by gamma motor neurons . depend on the muscle spindle receptors Activating alpha motor neurons Directly through supraspinal centers: Descending motor pathways (UMN) Indirectly through Muscle spindles Stretch reflex: skeletal muscles are shorter than the distance between its origin and insertion Gamma loop Gamma fibers activate the muscle fibers indirectly, while alpha fibers do it directly. -

The Syndrome of Acute Central Cervical Spinal Cord Injury by Richard C

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.21.3.216 on 1 August 1958. Downloaded from J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1958, 21, 216. THE SYNDROME OF ACUTE CENTRAL CERVICAL SPINAL CORD INJURY BY RICHARD C. SCHNEIDER, JOHN M. THOMPSON, and JOSE BEBIN From the Departments of Surgery and Sections of Neurosurgery of the University of Michigan Hospital, U.S. Veterans Hospital, and St. Joseph's Mercy Hospital, Ann Arbor, Michigan, and the Wayne County General Hospital, Eloise, Michigan, and the Department ofNeuropathology, University Hospital, Ann Arbor Any discussion of the diagnosis and treatment of tissue. The lower extremities tend to recover motor spinal cord injuries inevitably involves controversial power first, bladder function returns next, and finally strength in the upper extremities reappears, with the matters. Among the foremost of these are the indica- finer finger movements coming back last. The varying tions for (Schneider, 1951, 1955) and the contra- degrees of sensory impairment do not follow any set indications for (Schneider, Cherry, and Pantek, 1954) pattern of recovery." surgical intervention. It seems highly important, therefore, to establish criteria which will assist in It was first thought that the acute central cervical determining whether an operation should or should spinal cord injury was found only in severe hyper- Protected by copyright. not be undertaken. In 1955, a paper was published extension injuries. The importance of suspecting on " The Syndrome of Acute Central Cervical such an injury of the cervical spine in the presence Spinal Cord Injury" (Schneider et al., 1954), a of facial lacerations or contusions of the forehead syndrome the presence of which contraindicated any has been emphasized by Taylor and Blackwood surgical procedure. -

Central Nervous System. Sense Organs Study Guide

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM. SENSE ORGANS STUDY GUIDE 0 Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State University Medical Institute CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM. SENSE ORGANS STUDY GUIDE Recommended by the Academic Council of Sumy State University Sumy Sumy State University 2017 1 УДК 6.11.8 (072) C40 Authors: V. I. Bumeister, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor; O. S. Yarmolenko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant; O. O. Prykhodko, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Assistant Professor; L. G. Sulim, Senior Lecturer Reviewers: O. O. Sherstyuk – Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy (Poltava); V. Yu. Harbuzova – Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor of Sumy State University (Sumy) Recommended by for publication Academic Council of Sumy State University as a study guide (minutes № 11 of 15.06.2017) Central nervous system. Sense organs : study guide / C40 V. I. Bumeister, O. S. Yarmolenko, O. O. Prykhodko, L. G. Sulim. – Sumy : Sumy State University, 2017. – 173 p. ISBN 978-966-657- 694-4 This study gnide is intended for the students of medical higher educational institutions of IV accreditation level, who study human anatomy in the English language. Навчальний посібник рекомендований для студентів вищих медичних навчальних закладів IV рівня акредитації, які вивчають анатомію людини англійською мовою. УДК 6.11.8 (072) © Bumeister V. I., Yarmolenko O. S., Prykhodko O. O, Sulim L. G., 2017 ISBN 978-966-657- 694-4 © Sumy State University, 2017 2 INTRODUCTION Human anatomy is a scientific study of human body structure taking into consideration all its functions and mechanisms of its development. Studying the structure of separate organs and systems in close connection with their functions, anatomy considers a person's organism as a unit which develops basing on the regularities under the influence of internal and external factors during the whole process of evolution. -

Spinal Cord and Reflexes

Spinal Cord and Reflexes An Introduction 1 2 Spinal Cord – Cross Section 1. Sensory nerve 2. Motor nerve 3. Posterior root ganglion 4. Posterior root 5. Anterior root 6. Spinal nerve 7. Posterior white column 8. Anterior white column 9. Anterior grey horn 10. Posterior grey horn 11. Grey commissure 12. Central canal 13. Anterior median fissure 14. Posterior median fissure 15. Lateral white column 3 Spinal Cord Levels -- Anatomy 4 Spinal Cord Levels -- Physiology 5 Spinal Cord Levels – Clinical Applications 6 Dermatomes Dermatomes 1. Considerable overlap between neighboring dermatomes – as much as up to 8 dermatomes away 2. Borders are not exactly the same for touch as for pain and temperature 3. Dermatomes for pain and temp somewhat less extensive 4. Touch fibers belonging to a dorsal root overlap with those from neighboring roots moreso than do fibers for pain and temp. 7 Applications of Dermatomes • Intact Dermatomes • Lesions and Functional Goals 1. C3-5 = diaphragm = ok 1. C5 run electric wheelchair 2. C4 = shoulder shrugs = ok with mouth 3. C5 = deltoid and elbow flexes = 2. C6 feed self with clip-ons ok 3. C7 drive car with hand 4. C7 = wrist flexes = ok controls 5. C5-6 = biceps reflex = ok 4. C8 transfer by self to/from 6. C7 = triceps reflex = ok bed, auto, toilet 7. L2 = hip flexes = ok 5. T1-8 transfers self to/from tub 8. L3-4 = knee extends = ok 6. T9-12 ambulate with braces and crutches 9. L5-S1 = dorsiflexion = ok 7. S1-2 ambulate with cane 10. S1-S2 = plantarflexion = ok 8 Cord Overview 9 Spinal Cord Tracts – Physiology, too -- 1. -

Anatomy of the Spinal Cord

Anatomy of the Spinal Cord Neuroanatomy block-Anatomy-Lecture 2 Editing file Objectives At the end of the lecture, students should be able to: 1. Describe the external anatomy of the spinal cord. 2. Describe the internal anatomy of the spinal cord. 3. Describe the spinal nerves: formation, branches & distribution via plexuses. 4. Define Dermatome and describe its significance. 5. Describe the meninges of the spinal cord. 6. Define a reflex and reflex arc, and describe the components of the reflex arc. Color guide ● Only in boys slides in Green ● Only in girls slides in Purple ● important in Red ● Notes in Grey Spinal cord Function & Protection Features Shape & Pathway ● The primary function of ● Gives rise to 31 pairs of spinal ● It is elongated, cylindrical, thickness of spinal cord is nerves: the little finger,suspended in the vertebral a transmission of neural 8 Cervical, 12 Thoracic, canal signals between the brain 5 Lumbar, 5 Sacral, and the (PNS) then to the 1 Coccygeal. ● Continuous above with the medulla rest of the body by: oblongata. extends from foramen 1. Sensory. ● Spinal cord has two magnum to 2nd lumbar (L1-L2) vertebra. 2. Motor. enlargements: (In children it extends to L3). 3. Local reflexes. 1. Cervical enlargement: supplies In adults, its Length is upper limbs. approximately 45 cm ● Protected by vertebrae and 2. Lumbosacral enlargement: surrounded by the meninges supplies lower limbs ● The tapered inferior end forms Conus and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Medullaris, which is connected to the coccyx by a non-neuronal cord called Filum Terminale. ● The bundle of spinal nerves extending inferiorly from lumbosacral enlargement and conus medullaris surround the filum terminale and form cauda equina 3 Cross section of the Spinal cord ● The spinal cord is Incompletely ● Composed of grey matter in divided into two equal parts: the centre surrounded by Anteriorly by a short, shallow white matter supported by median fissure. -

University International

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

![1907-8.] Middle Cells of Grey Matter of Spinal Cord. 595](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9792/1907-8-middle-cells-of-grey-matter-of-spinal-cord-595-7289792.webp)

1907-8.] Middle Cells of Grey Matter of Spinal Cord. 595

1907-8.] Middle Cells of Grey Matter of Spinal Cord. 595 XXXVI.—The Middle Cells of the Grey Matter of the Spinal Cord. By J. H. Harvey Pirie, B.Sc, M.D., M.R.C.P. Ed. Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of M.D. Edin. Univ., 1907. {From the Pathological Department of the Royal Infirmary, Edinburgh.) Communicated by Dr ALEXANDER BRUCE. (With Two Plates.) (MS. received February 6, 1908. Read February 17, 1908.) THESE cells were first described and recognised as a separate and distinct group by Waldeyer (1). From his paper the following notes are taken:— " The middle cells are found at the junction of the anterior and posterior cornua, but especially in the former. They are small and medium-sized polygonal cells, arranged sometimes in a fairly compact group, sometimes more loosely scattered over a wider area. They are never so closely aggregated as are the cells of Clarke's column or those of the intermedio- lateral tract (Seitenhorn), but they are close enough to be regarded, especially in the upper cervical region, as a special nucleus of cells. Their situation varies somewhat in the different regions of the cord. As a group, they are most distinct in the upper cervical region. They lie here closely compacted to the outer side of, or a little in front of, Clarke's column. In the lower cervical region they form a less distinct group near Clarke's column, but quite internal to the postero-lateral motor group. In the upper dorsal region they are also abundant. They are situated laterally, and even somewhat posteriorly, to Clarke's column, extending into the posterior horn and into the scattered cells (Zerstreutenzellen) of the anterior cornu without a distinct limit. -

Motor Tracts

Motor tracts There are two major descending tracts Pyramidal tracts (Corticospinal ) : Conscious control of skeletal muscles Extrapyramidal: Upper motor Subconscious neurons. regulation of balance, muscle tone, eye, hand, and upper limb position: Vestibulospinal tracts Lower motor neurons. Reticulospinal tracts Rubrospinal tracts Tectospinal tracts Extrapyramidal tracts arise in the brainstem, but are under the influence of the cerebral cortex Rexed laminae • Lamina 8: motor interneurons, Commissural nucleus • Lamina 9: ventral horn, LMN, divided into nuclei: Ventromedial : all segements (extensors of vertebral coloumn) Dorsomedial : (T1-L2) intercostals and abdominal muscles Ventrolateral: C5-C8 (arm) L2-S2 (thigh) Dorsolateral: C5-C8 (Forearm), L3-S3 (Leg) Reterodorsolateral: C8-T1 (Hand), S1-S2 (foot) Central: Phrenic nerve (C3-C5) • Lamina X : Surrounds the central canal – the grey commissure Motor neurons of anterior horn Medial group: (All segments) Lateral group: only enlargements Brain stem • Stalk like in shape • Connects spinal cord to higher centers of forebrain Parts: 1. Medulla oblongata 2. Pons 3. Midbrain Motor tracts Both pyramidal tracts and extrapyramidal both starts from cortex: Area 4 Area 6 Area 312 Pyramidal: mainly from area 4 Extrapyramidal: mainly from area 6 area 6 Premotor area: uses external cues Suplemantary motor area: uses internal cues Lateral corticospinal tract The upper motor neurons of these tracts originate in the precentral gyrus of the cerebral cortex In midbrain:middle three- fifths of the basis pedunculi of the midbrain In medulla oblongata: pyramids Most of the fibers (85 percent) cross over (decussate) to the opposite side in the pyramidal decussation, where they continue to descend in the lateral funiculus of the spinal cord as the lateral corticospinal tract (LCST). -

Anatomy of the Spinal Cord

Anatomy of the spinal cord Done By: Samar AlOtaibi – Ghaida AlJamili "GIRLS SLIDES" Objectives: At the end of this lecture, the students should be able to : • Describe the external anatomy of the spinal cord. Dr.Najeeb notes: Green • Describe the internal anatomy of the spinal cord. Doctors' notes: Red • Describe the spinal nerves: formation, branches and distribution via plexuses. Extra notes& Summaries: Blue • Define ‘Dermatome’ and describe its significance. Editing File • Describe the meninges of the spinal cord. Define a reflex and reflex arc. Describe the components of • the reflex arc. Spinal Cord Terms: • An Elongated, almost Cylindrical structure, about the thickness of the Conus medullaris: The most distal bulbous part of the little finger. • It is suspended in the vertebral canal & spinal cord. surrounded--- by the meninges and Filum terminale "Termenal thread": is a delicate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). strand of fibrous tissue, about 20 cm in length, • In adults , its Length is approximately proceeding downward from the apex of the conus 45 cm medullaris • Extends from foramen magnum to L1- L2 • (In children it extends to L3) Notes: • Continuous above with the medulla oblongata. In children it extends to L3 so, we cannot give • The tapered inferior end forms conus medullaris, which is connected to the children spinal Anastasia to prevent spinal cord coccyx by a non-neuronal cord called injury. filum terminale. • Gives rise to 31 pairs of spinal nerves Terms: Spinal Meninges Epineurium: is the outermost layer of dense irregular • Three connective tissue membranes connective tissue surrounding a peripheral nerve. surround spinal cord and brain . Dura mater: tough outer layer, continuous P "Extension from the Dura mater" with epineurium of the spinal nerves Denticulate ligaments: The Pia mater of the spinal cord . -

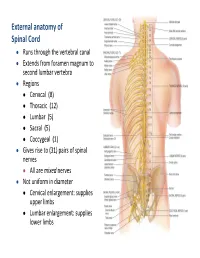

External Anatomy of Spinal Cord

External anatomy of Spinal Cord Runs through the vertebral canal Extends from foramen magnum to second lumbar vertebra Regions Cervical (8) Thoracic (12) Lumbar (5) Sacral (5) Coccygeal (1) Gives rise to (31) pairs of spinal nerves All are mixed nerves Not uniform in diameter Cervical enlargement: supplies upper limbs Lumbar enlargement: supplies lower limbs 10 11 Cross Section of Spinal Cord • l Rexed laminae • Lamina 1 relay information related to pain and temperature • Lamina 2: relay information related to pain and temperature (pain modulation) • Lamina 3 and 4: nucleus proprius; these laminae have many interneurons • Lamina 5: relay information related to pain and temperature • Lamina 6: presents only at the cervical and lumbar enlargements and receives proprioception • Lamina 7: Intermedio-lateral nucleus, contains preganglionic fibers of sympathetic (T1 -L2). Intermedio-medial nucleus ,all over the spinal cord, receive visceral pain. Dorsal nucleus of Clark’s presents at (C8 – L2 or T1- L4) , relay center for unconscious proprioception Rexed laminae • Lamina 8: motor interneurons, Commissural nucleus • Lamina 9: ventral horn, LMN, divided into nuclei: Ventromedial : all segements (extensors of vertebral coloumn) Dorsomedial : (T1-L2) intercostals and abdominal muscles Ventrolateral: C5-C8 (arm) L2-S2 (thigh) Dorsolateral: C5-C8 (Forearm), L3-S3 (Leg) Reterodorsolateral: C8-T1 (Hand), S1-S2 (foot) Central: Phrenic nerve (C3-C5) • Lamina X : Surrounds the central canal – the grey commissure Ascending tracts cervical -

Latin Term Latin Synonym UK English Term American English Term English

General Anatomy Latin term Latin synonym UK English term American English term English synonyms and eponyms Notes Termini generales General terms General terms Verticalis Vertical Vertical Horizontalis Horizontal Horizontal Medianus Median Median Coronalis Coronal Coronal Sagittalis Sagittal Sagittal Dexter Right Right Sinister Left Left Intermedius Intermediate Intermediate Medialis Medial Medial Lateralis Lateral Lateral Anterior Anterior Anterior Posterior Posterior Posterior Ventralis Ventral Ventral Dorsalis Dorsal Dorsal Frontalis Frontal Frontal Occipitalis Occipital Occipital Superior Superior Superior Inferior Inferior Inferior Cranialis Cranial Cranial Caudalis Caudal Caudal Rostralis Rostral Rostral Apicalis Apical Apical Basalis Basal Basal Basilaris Basilar Basilar Medius Middle Middle Transversus Transverse Transverse Longitudinalis Longitudinal Longitudinal Axialis Axial Axial Externus External External Internus Internal Internal Luminalis Luminal Luminal Superficialis Superficial Superficial Profundus Deep Deep Proximalis Proximal Proximal Distalis Distal Distal Centralis Central Central Periphericus Peripheral Peripheral One of the original rules of BNA was that each entity should have one and only one name. As part of the effort to reduce the number of recognized synonyms, the Latin synonym peripheralis was removed. The older, more commonly used of the two neo-Latin words was retained. Radialis Radial Radial Ulnaris Ulnar Ulnar Fibularis Peroneus Fibular Fibular Peroneal As part of the effort to reduce the number of synonyms, peronealis and peroneal were removed. Because perone is not a recognized synonym of fibula, peronealis is not a good term to use for position or direction in the lower limb. Tibialis Tibial Tibial Palmaris Volaris Palmar Palmar Volar Volar is an older term that is not used for other references such as palmar arterial arches, palmaris longus and brevis, etc.