Testimony, Witness, Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Time on Annual Journal of the New South Wales Australian Football History Society

Time on Annual Journal of the New South Wales Australian Football History Society 2019 Time on: Annual Journal of the New South Wales Australian Football History Society. 2019. Croydon Park NSW, 2019 ISSN 2202-5049 Time on is published annually by the New South Wales Australian Football Society for members of the Society. It is distributed to all current members free of charge. It is based on football stories originally published on the Society’s website during the current year. Contributions from members for future editions are welcome and should be discussed in the first instance with the president, Ian Granland on 0412 798 521 who will arrange with you for your tale to be submitted. Published by: The New South Wales Australian Football History Society Inc. ABN 48 204 892 073 40 Hampden Street, Croydon Park, NSW, 2133 P O Box 98, Croydon Park NSW 2133 Contents Editorial ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 2019: Announcement of the “Greatest Ever Players from NSW” ..................................................................... 3 Best NSW Team Ever Announced in May 2019 ......................................................................................... 4 The Make-Up of the NSW’s Greatest Team Ever ...................................................................................... 6 Famous footballing families of NSW ............................................................................................................... -

THE RISE of BOLTON DAVDISON EXTENDS STAY in MAGPIE NEST PASSION in the PRESIDENCY Inside

EDITION 13 $2.50 THE RISE OF BOLTON DAVDISON EXTENDS STAY IN MAGPIE NEST PASSION IN THE PRESIDENCY inside News 4 AFL Canberra Limited Bradman Stand Manuka Oval Manuka Circle ACT 2603 PO Box 3759, Manuka ACT 2603 Seniors 16-23 Ph 02 6228 0337 CHECK OUT OUR Fax 02 6232 7312 Reserves 24 Publisher Coordinate PO Box 1975 WODEN ACT 2606 Under 18’s 25 Ph 02 6162 3600 NEW WEBSITE! Email [email protected] Neither the editor, the publisher nor AFL Canberra accepts liability of any form for loss or harm of any type however caused All design material in the magazine is copyright protected and cannot be reproduced without the written www.coordinate.com.au permission of Coordinate. Editor Jamie Wilson Ph 02 6162 3600 Round 13 Email [email protected] Designer Logan Knight Ph 02 6162 3600 Email [email protected] vs Photography Andrew Trost Email [email protected] Manuka Oval, Sat 5th July, 2pm vs ANZ Stadium, Sat 5th July, 3:50pm vs Ainslie Oval, Sun 6th July, 2pm DESIGN + BRANDING + ADVERTISING + INTERNET Cover Photography GSP Images © 2008 In the box with the GM david wark We’re a happy team at Tuggeranong, we’re the might 8/ AFL Canberra distributes the Football Record to fighting Hawks…. hundreds of email address every week and division 1 What an incredible performance last week against all the scores are sent via sms to dozens weekly as well. (let me odds, or was it? know if you would like to be added to these databases) The Hawks have been building nicely and pushed a star 9/ The AFL Canberra website has the Record, game loaded Swans to within 4 goals the wee before. -

2018 Annual Financial Report

ANNUAL FINANCIAL REPORT HAWTHORN FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED | YEAR ENDING 31 OCTOBER 2018 | ACN 005 068 851 HAWTHORN FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED AND ITS CONTROLLED ENTITIES ACN 005 068 851 ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2018 HAWTHORNHawthorn Football FOOTBALL Club Limited CLUB and LIMITED its controlled entities AND ITS CONTROLLED ENTITIES CONTENTSContents Page Directors’ report 3 Lead auditor’s independence declaration 18 Statements of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 19 Statements of changes in equity 20 Statements of financial position 21 Statements of cash flows 22 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 23 Directors’ declaration 42 Independent auditor’s report 43 Appendix 1 – Foundation Report 45 hawthornfc.com.au 2 2 HAWTHORN FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED 3 AND ITS CONTROLLED ENTITIES DIRECTORS’ REPORT Hawthorn Football Club Limited and its controlled entities FORDirectors’ THE report YEAR ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2018 For the year ended 31 October 2018 The Directors present their report together with the financial report of Hawthorn Football Club Limited (“Club”) and the Group, (being the Club and its controlled entities), for the year ended 31 October 2018 and the auditor’s report thereon. Directors The Directors of te lub at an time during or since te end of te inancial ear are J ennett A (resident W anivell Vice-resident R J are A D oers ** A ae A L ristanson A * forer Vice-resident L olan R ali T Shearer R andenber * Appointed ice-resident 1 Februar 18, replaced L ristanson ** Retired rom te oard 1 December 17 *** Appointed to te oard 1 Februar 18 Principal Activities The principal activities of the Club are to compete within the Australian Football League (“AFL”) by maintaining, providing, supporting and controlling a tea of ootallers bearing te nae of te atorn Footall lub. -

Tiger Talk Claremont Football Club Inside This Issue

MARCH 2013 TTIGERTTIGERIIGGEERR TTALKTTALKAALLKK THE OFFICAL NEWSLETTER OF ONE TEAM WITH 2,589 KEY PLAYERS AND CLIMBING. CLAREMONT FOOTBALL CLUB INSIDE THIS ISSUE CFC REDEVELOPMENT MARC WEBB – MARK SEABY “ONE TEAM “ ARTICLE AND THE CHALLENGE INTERVIEW MARKETING PICTURES TO GO 3 IN A ROW PROMOTION · · · · “ www.claremontfc.com President’s Report Ken Venables - President On behalf of the Board of Directors I take this opportunity to wish you all a healthy, happy and successful 2013. It is that exciting time of the year again when Both gentlemen were co-opted on to the Board Perth and the Fremantle Dockers with Peel. the football season we have all been looking at the start of 2012. We also welcome Sam Whilst this decision was made by the football forward to is almost upon us. Our Senior Drabble to the Board this year as a co-optee. commission to involve both East Perth and Peel Coach, Marc Webb, has been coordinating very Sam is a descendant of the famous Drabble no other WAFL Club was invited to participate impressive pre-season sessions since full scale Hardware family business which was located in and nor were we consulted prior to the decision training resumed on January 17. Bay View Terrace. being announced. I must add however that this A great feeling continues within the player There is a huge year ahead of us off the fi eld football club was not, at any stage, interested group on the back of another incredibly with the demolition of our clubrooms at the in becoming involved. successful year in 2012, two magnifi cent end of the season. -

A'n ANALYSIS of the AFL FINAL EIGHT SYSTEM 1 Introduction

A'N ANALYSIS OF THE AFL FINAL EIGHT SYSTEM Jonathan Lowe and Stephen R. Clarke School of Mathematical Sciences Swinburne University PO Box 218 Hawthorn Victoria 3122, Australia Abstract An extensive analYsis· �to the n,ewfipal. eight system employed by ihe AFL. was unc�ertaken using_ certain crit�a a,s a benchmalk. An Excel Spreadsheet was-set up tq fully ex�e-every __possib.fe · __ _ outCome . .It was found that the new .syS�em failed-o� a nUmber of �portant-Criteria _::;uCh as t�e . 8.- probability of Premiership-decreaSing for lower-ranked teams,-and ·the most likely' sc�n·ario of · the grand final being the top two ranked sides. This makes the new system more unjuSt than the · · · previous Mcintyre Final Eight·system. 1 Introduction Recently, many deb�tes have occurred over the finals system played in Australian R.tiies f(mtball. The Australian Fo otball League {AFL), inresponse to public pressure, releaseda new finals system to replace the Mcintyre Final Eight system. Deipite a general acceptance of the system by the football clubs, a thorough statistical examination of this system is yet to be undertaken. It is the aim of this paper to examine the new system and to compare it to the previous Mcintyre Final Eight system. In 1931, the "Page Final Fo ur" system was put into place for the AFL finals. As the number of teams in the competition grew, so to did the number of finalists. The "Mcintyre Final Five" was introduced in 1972, and a system involving six teams was in place in 1991. -

Encyclopedia of Australian Football Clubs

Full Points Footy ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Volume One by John Devaney Published in Great Britain by Full Points Publications © John Devaney and Full Points Publications 2008 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission. Every effort has been made to ensure that this book is free from error or omissions. However, the Publisher and Author, or their respective employees or agents, shall not accept responsibility for injury, loss or damage occasioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of material in this book whether or not such injury, loss or damage is in any way due to any negligent act or omission, breach of duty or default on the part of the Publisher, Author or their respective employees or agents. Cataloguing-in-Publication data: The Full Points Footy Encyclopedia Of Australian Football Clubs Volume One ISBN 978-0-9556897-0-3 1. Australian football—Encyclopedias. 2. Australian football—Clubs. 3. Sports—Australian football—History. I. Devaney, John. Full Points Footy http://www.fullpointsfooty.net Introduction For most football devotees, clubs are the lenses through which they view the game, colouring and shaping their perception of it more than all other factors combined. To use another overblown metaphor, clubs are also the essential fabric out of which the rich, variegated tapestry of the game’s history has been woven. -

Feb 2010.Pub

March 2010 Williamstown Senior List 2010 Williamstown Football Club The Williamstown Football Club Coaching Staff have finalised our 2010 list. The 42 players comprise the P.O Box 307 following 20 players who have returned to the Seagulls. Williamstown 3016 2. Josh Young 7. David Stretton 36. Matthew Cravino 51. Nick DiMartino Ph: (03) 9391 0309 Fax: (03) 9391 5497 3. Ben Davies 9. Luke Cartelli 38. Dane Rampe 52. Dean Muir E: [email protected] 4. Ben Jolley 10. Brett Johnson (Capt) 42. Jordan Florance 56. Trent Lee 5. Cameron Lockwood 25. Michael Tanner 46. Dylan Ayton 62. Jacob Graham 6. Matthew Little 28. Matthew Grossman 50. Richard Knight 65. Nathan Uren The Williamstown Football Club have recruited 22 new players in 2010. Listed below are the players, their ages, clubs they have been recruited from and their 2010 jumper number. No. Player Name Recruited From : Age 8. Peter Faulks Casey Scorpions 21 12. Phil Smith Box Hill Hawks 20 13. Stephen McCallum Calder Cannons 18 15. Jeremy Mugavin Collingwood (VFL) 20 17. Nick Sing Gippsland Power 18 Stephen McCallum Peter Faulks 21. Adam Marangon Old Melbournians 19 27. Jack Purton-Smith Sandringham Dragons 18 39. Michael Fogarty Western Jets 18 40. Dion Lawson Western Jets 18 47. Tom German Essendon 19 53. Brian Fenton Bendigo Pioneers 18 54. Jye Sandiford Bendigo Pioneers 18 Phil Smith Nick Sing 55. Jake Wilson Portland 18 57. Hayden Armstrong Marist College (ACT) 18 956 1958 1959 1969 1976 1986 1990 2003 58. Jake De Sousa Coburg 22 59. Josh Griffiths Northern Knights 18 60. -

Unrivalled MCG.ORG.AU/HOSPITALITY Your Guide to Corporate Suites and Experiences in 2018/19

Premium Experiences Unrivalled MCG.ORG.AU/HOSPITALITY Your guide to corporate suites and experiences in 2018/19. An Australian icon The Melbourne Cricket Ground was built in 1853 and since then, has established a marvellous history that compares favourably with any of the greatest sporting arenas in the world. Fondly referred to as the ‘G, Australia’s favourite stadium has hosted Olympic and Commonwealth Games, is the birthplace of Test Cricket and the home of Australian Rules Football. Holding more than 80 events annually and attracting close to four million people, the MCG has hosted more than 100 Test matches (including the first in 1877) and is home to a blockbuster events calendar including the traditional Boxing Day Test and the AFL Grand Final. MCG EST. 1853 EST. MCG THE PINNACLE OF TEST CRICKET AND THE HOME OF AUSTRALIAN RULES FOOTBALL CORPORATE SUITE LEASING Many of Australia’s leading businesses choose to entertain their clients and staff in the unique and relaxed environment of their very own corporate suite at the iconic MCG. CORPORATE SUITE LEASING 2018/19 CORPORATE Designed to offer first-class amenities, personal service and an exclusive environment, an MCG corporate suite is the perfect setting to entertain, reward employees or enjoy an event with friends in capacities ranging from 10-20 guests. Corporate suite holders are guaranteed access to all AFL home and away matches scheduled at the MCG, AFL Finals series matches including the AFL Grand Final, and international cricket matches at the MCG, headlined by the renowned Boxing Day Test. You will also enjoy; - Two VIP underground car park passes - Company branding facing the ground - Two additional suite entry tickets to all events - Non-match day access for business meetings THE YEAR AWAITS There are plenty of exciting events to look forward to at the MCG in 2018, headlined by the AFL Grand Final, and the Boxing Day Test. -

Club and AFL Members Received Free Entry to NAB Challenge Matches and Ticket Prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series Were Held at 2013 Levels

COMMERCIAL OPERATIONS DARREN BIRCH GENERAL MANAGER Club and AFL members received free entry to NAB Challenge matches and ticket prices for the Toyota AFL Finals Series were held at 2013 levels. eason 2015 was all about the with NAB and its continued support fans, with the AFL striving of the AFL’s talent pathway. to improve the affordability The AFL welcomed four new of attending matches and corporate partners in CrownBet, enhancing the fan experience Woolworths, McDonald’s and 2XU to at games. further strengthen the AFL’s ongoing SFor the first time in more than 10 development of commercial operations. years, AFL and club members received AFL club membership continued free general admission entry into NAB to break records by reaching a total of Challenge matches in which their team 836,136 members nationally, a growth was competing, while the price of base of 3.93 per cent on 2014. general admission tickets during the In season 2015, the Marketing and Toyota Premiership Season remained the Research Insights team moved within the same level as 2014. Commercial Operations team, ensuring PRIDE OF SOUTH AUSTRALIA Fans attending the Toyota AFL Finals greater integration across membership, The Showdown rivalry between Eddie Betts’ Series and Grand Final were also greeted to ticketing and corporate partners. The Adelaide Crows and Port ticket prices at the same level as 2013, after a Research Insights team undertook more Adelaide continued in 2015, price freeze for the second consecutive year. than 60 projects, allowing fans, via the with the round 16 clash drawing a record crowd NAB AFL Auskick celebrated 20 years, ‘Fan Focus’ panel, to influence future of 53,518. -

2009 AFL Annual Report

CHAIRMAN’S REPORT MIKE FITZPATRICK CEO’S REPORT ANDREW DEMETRIOU UUniquenique ttalent:alent: HHawthorn'sawthorn's CCyrilyril RRioliioli iiss a ggreatreat eexamplexample ofof thethe sskill,kill, ggameame ssenseense aandnd fl aairir aann eever-growingver-growing nnumberumber ooff IIndigenousndigenous pplayerslayers bbringring ttoo tthehe ccompetition.ompetition. CHAIRMAN'S REPORT Mike Fitzpatrick Consensus the key to future growth In many areas, key stakeholders worked collaboratively to ensure progress. n late 2006 when the AFL Commission released its » An important step to provide a new home for AFL matches in Next Generation fi nancial strategy for the period 2007-11, Adelaide occurred when the South Australian National we outlined our plans to expand the AFL competition and Football League (SANFL) and South Australian Cricket to grow our game nationally. Those plans advanced Association (SACA) signed a memorandum of understanding to Isignifi cantly in 2009 when some very tangible foundations redevelop Adelaide Oval as a new home for football and cricket. were laid upon which the two new AFL clubs based on the Gold » Attendances, club membership and national television audiences Coast and in Greater Western Sydney will be built. Overall, 2009 continued to make the AFL Australia’s most popular professional delivered various outcomes for the AFL competition and the game sporting competition. at a community level, which were highlighted by the following: » Participation in the game at a community level reached a » Work started on the redevelopment of the Gold Coast Stadium record of more than 732,000 registered participants. after funding was secured for the project. » A new personal conduct policy, adopted by the AFL » The AFL Commission issued a licence to Gold Coast Football Commission in late 2008, was implemented in 2009. -

Annual Financial Report

Annual Financial Report HAWTHORN FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED YEAR ENDING 31 OCTOBER 2015 Year ending 31 October 2013 ACN 005 068 851 Hawthorn Football Club Limited and its controlled entities ACN 005 068 851 Annual report for the year ended 31 October 2015 2 Hawthorn Football Club Limited and its controlled entities HawthornCONTENTS Football Club Limited and its controlled entities Contents PAGE Page Directors’ report 33 Lead auditor’s independence declaration 14 Statements of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 15 Statements of changes in equity 16 Statements of financial position 17 Statements of cash flow s 18 Notes to the consolidated financial statements 19 Directors’ declaration 3388 Independent auditor’s report 3399 Appendix 1 – Foundation Report 4041 2 hawthornfc.com.au 2 3 Hawthorn Football Club Limited and its controlled entities DIRECTORS’Hawthorn Football REPORT Club Limited and its controlled entities FORDirectors’ THE YEAR report ENDED 31 OCTOBER 2015 For the year ended 31 October 2015 The Directors present their report together with the financial report of Hawthorn Football Club Limited (“ the Club” ) and the Group, (being the Club and its controlled entities), for the year ended 31 October 2015 and the auditor’s report thereon. Directors The Directors of the Club at any time during or since the end of the financial year are: P A Newbold (President) R J Garvey (Vice-President) M K Ralston (former Vice-President)* R C Am os A D W Gowers A H Kaye L J Kristjanson P W Nankivell* * B A Stevenson * Retired from the board 11 December 2014 ** Appointed to the board 11 December 2014 Principal activities The principal activities of the Club are to compete within the Australian Football League (AFL) by maintaining, providing, supporting and controlling a team of footballers bearing the name of the Hawthorn Football Club. -

2020 TOYOTA AFL GRAND FINAL the GABBA ACCESSIBLE NEEDS SEATING REQUEST FORM Please Complete and Submit the Below To

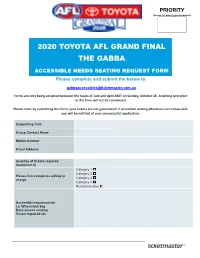

PRIORITY (please list priority group number) 2020 TOYOTA AFL GRAND FINAL THE GABBA ACCESSIBLE NEEDS SEATING REQUEST FORM Please complete and submit the below to [email protected] Forms are only being accepted between the hours of 7am and 4pm AEST on Sunday, October 18. Anything sent prior to this time will not be considered. Please note: by submitting this form, your tickets are not guaranteed. If accessible seating allocations are exhausted, you will be notified of your unsuccessful application. Supporting Club Group Contact Name Mobile Number Email Address Quantity of tickets required (maximum 6) Category 1 ☐ Category 2 ☐ Please tick categories willing to Category 3 ☐ accept Category 4 ☐ Restricted View ☐ Accessible requirements: i.e. Wheelchair bay Easy access seating Vision impaired etc. It is a requirement from Queensland Health to provide the information for all members for contact tracing purposes. Please complete the information below for all members who you are wanting to attend the 2020 Toyota AFL Grand Final with. Member #1 Priority Group ☐ Priority 1 ☐ Priority 2 ☐ Priority 3 Member Name Mobile phone number Email address Membership barcode number Companion card number (if applicable) ☐ You acknowledge that you are not entering The Gabba from a known banned area, hotspot or currently serving a mandated 14 day quarantine period & you accept the AFL’s acknowledgement of risk. To be able to book your tickets, please tick the box. Member #2 Priority Group ☐ Priority 1 ☐ Priority 2 ☐ Priority 3 Member Name Mobile phone number Email address Membership barcode number Companion card number (if applicable) ☐ You acknowledge that you are not entering The Gabba from a known banned area, hotspot or currently serving a mandated 14 day quarantine period & you accept the AFL’s acknowledgement of risk.