Atomic Structure and the Periodic Table the Electronic Structure of an Atom Determines Its Characteristics Studying Atoms by Analyzing Light Emissions/Absorptions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomic Orbitals

Visualization of Atomic Orbitals Source: Robert R. Gotwals, Jr., Department of Chemistry, North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics, Durham, NC, 27705. Email: [email protected]. Copyright ©2007, all rights reserved, permission to use for non-commercial educational purposes is granted. Introductory Readings Where are the electrons in an atom? There are a number of Models - a description of models that look to describe the location and behavior of some physical object or electrons in atoms. It is important to know this information, as behavior in nature. Models it helps chemists to make statements and predictions about are often mathematical, describing the behavior of how atoms will react with other atoms to form molecules. The some event. model one chooses will oftentimes influence the types of statements one can make about the behavior – that is, the reactivity – of an atom or group of atoms. Bohr model - states that no One model, the Bohr model, describes electrons as small two electrons in an atom can billiard balls, rotating around the positively charged nucleus, have the same set of four much in the way that planets quantum numbers. orbit around the Sun. The placement and motion of electrons are found in fixed and quantifiable levels called orbits, Orbits- where electrons are or, in older terminology, shells. believed to be located in the There are specific numbers of Bohr model. Orbits have a electrons that can be found in fixed amount of energy, and are identified with the each orbit – 2 for the first orbit, principle quantum number 8 for the second, and so forth. -

Group Problems #22 - Solutions

Group Problems #22 - Solutions Friday, October 21 Problem 1 Ritz Combination Principle Show that the longest wavelength of the Balmer series and the longest two wavelengths of the Lyman series satisfy the Ritz Combination Principle. The wavelengths corresponding to transitions between two energy levels in hydrogen is given by: n2 λ = λlimit 2 2 ; (1) n − n0 where n0 = 1 for the Lyman series, n0 = 2 for the Balmer series, and λlimit = 91:1 nm for the Lyman series and λlimit = 364:5 nm for the Balmer series. Inspection of this equation shows that the longest wavelength corresponds to the transition between n = n0 and n = n0 + 1. Thus, for the Lyman series, the longest two wavelengths are λ12 and λ13. For the Balmer series, the longest wavelength is λ23. The Ritz combination principle states that certain pairs of observed frequencies from the hydrogen spectrum add together to give other observed frequencies. For this particular problem, we then have: ν12 + ν23 = ν13 =) h(ν12 + ν23) = hν13 (2) 1 1 1 =) hc + = hc (3) λ12 λ23 λ13 1 1 1 =) + = : (4) λ12 λ23 λ13 Inverting Eqn. 1 above gives: 2 2 2 1 1 n − n0 1 n0 = 2 = 1 − 2 : (5) λ λlimit n λlimit n To calculate 1/λ12 and 1/λ13, we use the Lyman series numbers and find 1/λ12 = −1 −1 3=(4 ∗ 91:1) = 0:00823 nm and 1/λ13 = 8=(9 ∗ 91:1) = 0:00976 nm . To compute 1/λ23, we use the Balmer series numbers and find 1/λ23 = 5=(9 ∗ 364:5) = 0:00152 −1 nm . -

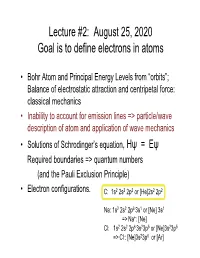

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal Is to Define Electrons in Atoms

Lecture #2: August 25, 2020 Goal is to define electrons in atoms • Bohr Atom and Principal Energy Levels from “orbits”; Balance of electrostatic attraction and centripetal force: classical mechanics • Inability to account for emission lines => particle/wave description of atom and application of wave mechanics • Solutions of Schrodinger’s equation, Hψ = Eψ Required boundaries => quantum numbers (and the Pauli Exclusion Principle) • Electron configurations. C: 1s2 2s2 2p2 or [He]2s2 2p2 Na: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s1 or [Ne] 3s1 => Na+: [Ne] Cl: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s23p5 or [Ne]3s23p5 => Cl-: [Ne]3s23p6 or [Ar] What you already know: Quantum Numbers: n, l, ml , ms n is the principal quantum number, indicates the size of the orbital, has all positive integer values of 1 to ∞(infinity) (Bohr’s discrete orbits) l (angular momentum) orbital 0s l is the angular momentum quantum number, 1p represents the shape of the orbital, has integer values of (n – 1) to 0 2d 3f ml is the magnetic quantum number, represents the spatial direction of the orbital, can have integer values of -l to 0 to l Other terms: electron configuration, noble gas configuration, valence shell ms is the spin quantum number, has little physical meaning, can have values of either +1/2 or -1/2 Pauli Exclusion principle: no two electrons can have all four of the same quantum numbers in the same atom (Every electron has a unique set.) Hund’s Rule: when electrons are placed in a set of degenerate orbitals, the ground state has as many electrons as possible in different orbitals, and with parallel spin. -

Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values

268 A Textbook of Physical Chemistry – Volume I Principal, Azimuthal and Magnetic Quantum Numbers and the Magnitude of Their Values The Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen and hydrogen-like species in the polar coordinates can be written as: 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕 휕휓 1 휕2휓 8휋2휇 푍푒2 (406) [ (푟2 ) + (푆푖푛휃 ) + ] + (퐸 + ) 휓 = 0 푟2 휕푟 휕푟 푆푖푛휃 휕휃 휕휃 푆푖푛2휃 휕휙2 ℎ2 푟 After separating the variables present in the equation given above, the solution of the differential equation was found to be 휓푛,푙,푚(푟, 휃, 휙) = 푅푛,푙. 훩푙,푚. 훷푚 (407) 2푍푟 푘 (408) 3 푙 푘=푛−푙−1 (−1)푘+1[(푛 + 푙)!]2 ( ) 2푍 (푛 − 푙 − 1)! 푍푟 2푍푟 푛푎 √ 0 = ( ) [ 3] . exp (− ) . ( ) . ∑ 푛푎0 2푛{(푛 + 푙)!} 푛푎0 푛푎0 (푛 − 푙 − 1 − 푘)! (2푙 + 1 + 푘)! 푘! 푘=0 (2푙 + 1)(푙 − 푚)! 1 × √ . 푃푚(퐶표푠 휃) × √ 푒푖푚휙 2(푙 + 푚)! 푙 2휋 It is obvious that the solution of equation (406) contains three discrete (n, l, m) and three continuous (r, θ, ϕ) variables. In order to be a well-behaved function, there are some conditions over the values of discrete variables that must be followed i.e. boundary conditions. Therefore, we can conclude that principal (n), azimuthal (l) and magnetic (m) quantum numbers are obtained as a solution of the Schrodinger wave equation for hydrogen atom; and these quantum numbers are used to define various quantum mechanical states. In this section, we will discuss the properties and significance of all these three quantum numbers one by one. Principal Quantum Number The principal quantum number is denoted by the symbol n; and can have value 1, 2, 3, 4, 5…..∞. -

Vibrational Quantum Number

Fundamentals in Biophotonics Quantum nature of atoms, molecules – matter Aleksandra Radenovic [email protected] EPFL – Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne Bioengineering Institute IBI 26. 03. 2018. Quantum numbers •The four quantum numbers-are discrete sets of integers or half- integers. –n: Principal quantum number-The first describes the electron shell, or energy level, of an atom –ℓ : Orbital angular momentum quantum number-as the angular quantum number or orbital quantum number) describes the subshell, and gives the magnitude of the orbital angular momentum through the relation Ll2 ( 1) –mℓ:Magnetic (azimuthal) quantum number (refers, to the direction of the angular momentum vector. The magnetic quantum number m does not affect the electron's energy, but it does affect the probability cloud)- magnetic quantum number determines the energy shift of an atomic orbital due to an external magnetic field-Zeeman effect -s spin- intrinsic angular momentum Spin "up" and "down" allows two electrons for each set of spatial quantum numbers. The restrictions for the quantum numbers: – n = 1, 2, 3, 4, . – ℓ = 0, 1, 2, 3, . , n − 1 – mℓ = − ℓ, − ℓ + 1, . , 0, 1, . , ℓ − 1, ℓ – –Equivalently: n > 0 The energy levels are: ℓ < n |m | ≤ ℓ ℓ E E 0 n n2 Stern-Gerlach experiment If the particles were classical spinning objects, one would expect the distribution of their spin angular momentum vectors to be random and continuous. Each particle would be deflected by a different amount, producing some density distribution on the detector screen. Instead, the particles passing through the Stern–Gerlach apparatus are deflected either up or down by a specific amount. -

Observations of the Lyman Series Forest Towards the Redshift 7.1 Quasar ULAS J1120+0641 R

A&A 601, A16 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201630258 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics Observations of the Lyman series forest towards the redshift 7.1 quasar ULAS J1120+0641 R. Barnett1, S. J. Warren1, G. D. Becker2, D. J. Mortlock1; 3; 4, P. C. Hewett5, R. G. McMahon5; 6, C. Simpson7, and B. P. Venemans8 1 Astrophysics Group, Blackett Laboratory, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of California, Riverside, 900 University Avenue, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 3 Department of Mathematics, Imperial College London, London SW7 2AZ, UK 4 Department of Astronomy, Stockholm University, Albanova, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden 5 Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 6 Kavli Institute for Cosmology, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK 7 Gemini Observatory, Northern Operations Center, N. A’ohoku Place, Hilo, HI 96720, USA 8 Max-Planck Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany Received 15 December 2016 / Accepted 9 February 2017 ABSTRACT We present a 30 h integration Very Large Telescope X-shooter spectrum of the Lyman series forest towards the z = 7:084 quasar ULAS J1120+0641. The only detected transmission at S=N > 5 is confined to seven narrow spikes in the Lyα forest, over the redshift range 5:858 < z < 6:122, just longward of the wavelength of the onset of the Lyβ forest. There is also a possible detection of one further unresolved spike in the Lyβ forest at z = 6:854, with S=N = 4:5. -

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom

The Quantum Mechanical Model of the Atom Quantum Numbers In order to describe the probable location of electrons, they are assigned four numbers called quantum numbers. The quantum numbers of an electron are kind of like the electron’s “address”. No two electrons can be described by the exact same four quantum numbers. This is called The Pauli Exclusion Principle. • Principle quantum number: The principle quantum number describes which orbit the electron is in and therefore how much energy the electron has. - it is symbolized by the letter n. - positive whole numbers are assigned (not including 0): n=1, n=2, n=3 , etc - the higher the number, the further the orbit from the nucleus - the higher the number, the more energy the electron has (this is sort of like Bohr’s energy levels) - the orbits (energy levels) are also called shells • Angular momentum (azimuthal) quantum number: The azimuthal quantum number describes the sublevels (subshells) that occur in each of the levels (shells) described above. - it is symbolized by the letter l - positive whole number values including 0 are assigned: l = 0, l = 1, l = 2, etc. - each number represents the shape of a subshell: l = 0, represents an s subshell l = 1, represents a p subshell l = 2, represents a d subshell l = 3, represents an f subshell - the higher the number, the more complex the shape of the subshell. The picture below shows the shape of the s and p subshells: (notice the electron clouds) • Magnetic quantum number: All of the subshells described above (except s) have more than one orientation. -

4 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance

Chapter 4, page 1 4 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Pieter Zeeman observed in 1896 the splitting of optical spectral lines in the field of an electromagnet. Since then, the splitting of energy levels proportional to an external magnetic field has been called the "Zeeman effect". The "Zeeman resonance effect" causes magnetic resonances which are classified under radio frequency spectroscopy (rf spectroscopy). In these resonances, the transitions between two branches of a single energy level split in an external magnetic field are measured in the megahertz and gigahertz range. In 1944, Jevgeni Konstantinovitch Savoiski discovered electron paramagnetic resonance. Shortly thereafter in 1945, nuclear magnetic resonance was demonstrated almost simultaneously in Boston by Edward Mills Purcell and in Stanford by Felix Bloch. Nuclear magnetic resonance was sometimes called nuclear induction or paramagnetic nuclear resonance. It is generally abbreviated to NMR. So as not to scare prospective patients in medicine, reference to the "nuclear" character of NMR is dropped and the magnetic resonance based imaging systems (scanner) found in hospitals are simply referred to as "magnetic resonance imaging" (MRI). 4.1 The Nuclear Resonance Effect Many atomic nuclei have spin, characterized by the nuclear spin quantum number I. The absolute value of the spin angular momentum is L =+h II(1). (4.01) The component in the direction of an applied field is Lz = Iz h ≡ m h. (4.02) The external field is usually defined along the z-direction. The magnetic quantum number is symbolized by Iz or m and can have 2I +1 values: Iz ≡ m = −I, −I+1, ..., I−1, I. -

Chemical Bonding & Chemical Structure

Chemistry 201 – 2009 Chapter 1, Page 1 Chapter 1 – Chemical Bonding & Chemical Structure ings from inside your textbook because I normally ex- Getting Started pect you to read the entire chapter. 4. Finally, there will often be a Supplement that con- If you’ve downloaded this guide, it means you’re getting tains comments on material that I have found espe- serious about studying. So do you already have an idea cially tricky. Material that I expect you to memorize about how you’re going to study? will also be placed here. Maybe you thought you would read all of chapter 1 and then try the homework? That sounds good. Or maybe you Checklist thought you’d read a little bit, then do some problems from the book, and just keep switching back and forth? That When you have finished studying Chapter 1, you should be sounds really good. Or … maybe you thought you would able to:1 go through the chapter and make a list of all of the impor- tant technical terms in bold? That might be good too. 1. State the number of valence electrons on the following atoms: H, Li, Na, K, Mg, B, Al, C, Si, N, P, O, S, F, So what point am I trying to make here? Simply this – you Cl, Br, I should do whatever you think will work. Try something. Do something. Anything you do will help. 2. Draw and interpret Lewis structures Are some things better to do than others? Of course! But a. Use bond lengths to predict bond orders, and vice figuring out which study methods work well and which versa ones don’t will take time. -

Unique Astrophysics in the Lyman Ultraviolet

Unique Astrophysics in the Lyman Ultraviolet Jason Tumlinson1, Alessandra Aloisi1, Gerard Kriss1, Kevin France2, Stephan McCandliss3, Ken Sembach1, Andrew Fox1, Todd Tripp4, Edward Jenkins5, Matthew Beasley2, Charles Danforth2, Michael Shull2, John Stocke2, Nicolas Lehner6, Christopher Howk6, Cynthia Froning2, James Green2, Cristina Oliveira1, Alex Fullerton1, Bill Blair3, Jeff Kruk7, George Sonneborn7, Steven Penton1, Bart Wakker8, Xavier Prochaska9, John Vallerga10, Paul Scowen11 Summary: There is unique and groundbreaking science to be done with a new generation of UV spectrographs that cover wavelengths in the “Lyman Ultraviolet” (LUV; 912 - 1216 Å). There is no astrophysical basis for truncating spectroscopic wavelength coverage anywhere between the atmospheric cutoff (3100 Å) and the Lyman limit (912 Å); the usual reasons this happens are all technical. The unique science available in the LUV includes critical problems in astrophysics ranging from the habitability of exoplanets to the reionization of the IGM. Crucially, the local Universe (z ≲ 0.1) is entirely closed to many key physical diagnostics without access to the LUV. These compelling scientific problems require overcoming these technical barriers so that future UV spectrographs can extend coverage to the Lyman limit at 912 Å. The bifurcated history of the Space UV: Much the course of space astrophysics can be traced to the optical properties of ozone (O3) and magnesium fluoride (MgF2). The first causes the space UV, and the second divides the “HST UV” (1150 - 3100 Å) and the “FUSE UV” (900 - 1200 Å). This short paper argues that some critical problems in astrophysics are best solved by a future generation of high-resolution UV spectrographs that observe all wavelengths between the Lyman limit and the atmospheric cutoff. -

Electron Configurations, Orbital Notation and Quantum Numbers

5 Electron Configurations, Orbital Notation and Quantum Numbers Electron Configurations, Orbital Notation and Quantum Numbers Understanding Electron Arrangement and Oxidation States Chemical properties depend on the number and arrangement of electrons in an atom. Usually, only the valence or outermost electrons are involved in chemical reactions. The electron cloud is compartmentalized. We model this compartmentalization through the use of electron configurations and orbital notations. The compartmentalization is as follows, energy levels have sublevels which have orbitals within them. We can use an apartment building as an analogy. The atom is the building, the floors of the apartment building are the energy levels, the apartments on a given floor are the orbitals and electrons reside inside the orbitals. There are two governing rules to consider when assigning electron configurations and orbital notations. Along with these rules, you must remember electrons are lazy and they hate each other, they will fill the lowest energy states first AND electrons repel each other since like charges repel. Rule 1: The Pauli Exclusion Principle In 1925, Wolfgang Pauli stated: No two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers. This means no atomic orbital can contain more than TWO electrons and the electrons must be of opposite spin if they are to form a pair within an orbital. Rule 2: Hunds Rule The most stable arrangement of electrons is one with the maximum number of unpaired electrons. It minimizes electron-electron repulsions and stabilizes the atom. Here is an analogy. In large families with several children, it is a luxury for each child to have their own room. -

![Arxiv:1704.03416V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 11 Apr 2017 2](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7765/arxiv-1704-03416v1-astro-ph-ga-11-apr-2017-2-777765.webp)

Arxiv:1704.03416V1 [Astro-Ph.GA] 11 Apr 2017 2

Physics of Lyα Radiative Transfer Mark Dijkstra (Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Oslo) (Dated: April 7, 2017) Lecture notes for the 46th Saas-Fee winterschool, 13-19 March 2016, Les Diablerets, Switzerland. See http://obswww.unige.ch/Courses/saas-fee-2016/ arXiv:1704.03416v1 [astro-ph.GA] 11 Apr 2017 2 Contents 1. Preface 3 2. Introduction 3 3. The Hydrogen Atom and Introduction to Lyα Emission Mechanisms 4 3.1. Hydrogen in our Universe 4 3.2. The Hydrogen Atom: The Classical & Quantum Picture 6 3.3. Radiative Transitions in the Hydrogen Atom: Lyman, Balmer, ..., Pfund, .... Series 8 3.4. Lyα Emission Mechanisms 9 4. A Closer Look at Lyα Emission Mechanisms & Sources 10 4.1. Collisions 10 4.2. Recombination 13 5. Astrophysical Lyα Sources 14 5.1. Interstellar HII Regions 14 5.2. The Circumgalactic/Intergalactic Medium (CGM/IGM) 16 6. Step 1 Towards Understanding Lyα Radiative Transfer: Lyα Scattering Cross-section 22 6.1. Interaction of a Free Electron with Radiation: Thomson Scattering 22 6.2. Interaction of a Bound Electron with Radiation: Lorentzian Cross-section 25 6.3. Interaction of a Bound Electron with Radiation: Relation to Lyα Cross-Section 26 6.4. Voigt Profile of Lyα Cross-Section 27 7. Step 2 Towards Understanding Lyα Radiative Transfer: The Radiative Transfer Equation 29 7.1. I: Absorption Term: Lyα Cross Section 30 7.2. II: Volume Emission Term 30 7.3. III: Scattering Term 30 7.4. IV: ‘Destruction’ Term 36 7.5. Lyα Propagation through HI: Scattering as Double Diffusion Process 38 8.