CEREBELLAR DISORDERS Mov5 (1)

Total Page:16

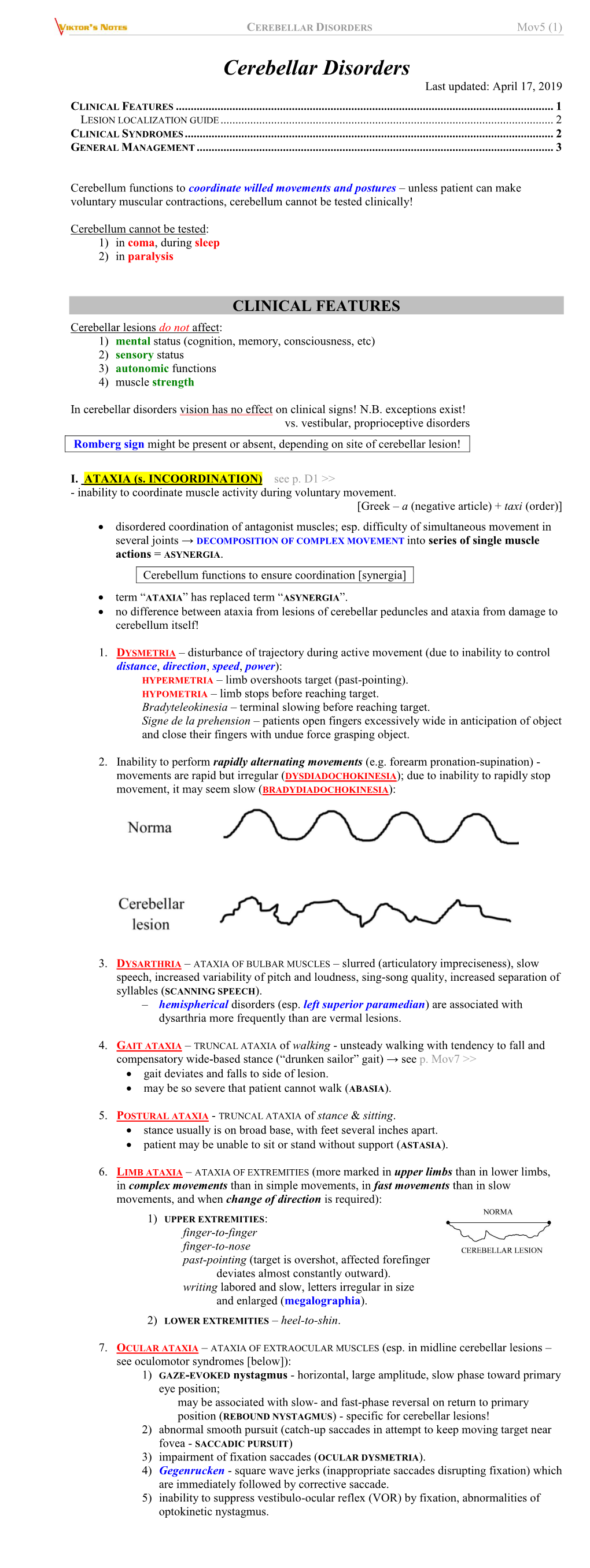

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiplex Families with Multiple System Atrophy

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Multiplex Families With Multiple System Atrophy Kenju Hara, MD, PhD; Yoshio Momose, MD, PhD; Susumu Tokiguchi, MD, PhD; Mitsuteru Shimohata, MD, PhD; Kenshi Terajima, MD, PhD; Osamu Onodera, MD, PhD; Akiyoshi Kakita, MD, PhD; Mitsunori Yamada, MD, PhD; Hitoshi Takahashi, MD, PhD; Motoyuki Hirasawa, MD, PhD; Yoshikuni Mizuno, MD, PhD; Katsuhisa Ogata, MD, PhD; Jun Goto, MD, PhD; Ichiro Kanazawa, MD, PhD; Masatoyo Nishizawa, MD, PhD; Shoji Tsuji, MD, PhD Background: Multiple system atrophy (MSA) has Results: Consanguineous marriage was observed in 1 been considered a sporadic disease, without patterns of of 4 families. Among 8 patients, 1 had definite MSA, 5 inheritance. had probable MSA, and 2 had possible MSA. The most frequent phenotype was MSA with predominant parkin- Objective: To describe the clinical features of 4 multi- sonism, observed in 5 patients. Six patients showed pon- plex families with MSA, including clinical genetic tine atrophy with cross sign or slitlike signal change at aspects. the posterolateral putaminal margin or both on brain mag- netic resonance imaging. Possibilities of hereditary atax- Design: Clinical and genetic study. ias, including SCA1 (ataxin 1, ATXN1), SCA2 (ATXN2), Machado-Joseph disease/SCA3 (ATXN1), SCA6 (ATXN1), Setting: Four departments of neurology in Japan. SCA7 (ATXN7), SCA12 (protein phosphatase 2, regula- tory subunit B,  isoform; PP2R2B), SCA17 (TATA box Patients: Eight patients in 4 families with parkinson- binding protein, TBP) and DRPLA (atrophin 1; ATN1), ism, cerebellar ataxia, and autonomic failure with age at ␣ onset ranging from 58 to 72 years. Two siblings in each were excluded, and no mutations in the -synuclein gene family were affected with these conditions. -

Reframing Psychiatry for Precision Medicine

Reframing Psychiatry for Precision Medicine Elizabeth B Torres 1,2,3* 1 Rutgers University Department of Psychology; [email protected] 2 Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science (RUCCS) 3 Rutgers University Computer Science, Center for Biomedicine Imaging and Modelling (CBIM) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: (011) +858-445-8909 (E.B.T) Supplementary Material Sample Psychological criteria that sidelines sensory motor issues in autism: The ADOS-2 manual [1, 2], under the “Guidelines for Selecting a Module” section states (emphasis added): “Note that the ADOS-2 was developed for and standardized using populations of children and adults without significant sensory and motor impairments. Standardized use of any ADOS-2 module presumes that the individual can walk independently and is free of visual or hearing impairments that could potentially interfere with use of the materials or participation in specific tasks.” Sample Psychiatric criteria from the DSM-5 [3] that does not include sensory-motor issues: A. Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive, see text): 1. Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions. 2. Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication. -

Non-Progressive Congenital Ataxia with Cerebellar Hypoplasia in Three Families

248 Non-progressive congenital ataxia with cerebellar hypoplasia in three families . No 1.6 Z. YAPICI & M. ERAKSOY . .. I.Y.. \ .~ ---················ No of Neurology, of Child Neuro/ogy, Facu/ty of Turkey Abstract Non-progressive with cerebellar hypoplasia are a rarely seen heterogeneous group ofhereditary cerebellar ataxias. Three sib pairs from three different families with this entity have been reviewed, and differential diagnosis has been di sc ussed. in two of the families, the parents were consanguineous. Walking was delayed in ali the children. Truncal and extremiry were then noticed. Ataxia was severe in one child, moderate in two children, and mild in the remaining revealed horizontal, horizonto-rotatory and/or vertical variable degrees ofmental and pvramidal signs besides truncal and extremity ataxia. In ali the cases, cerebellar hemisphere and vermis were in MRI . During the follow-up period, a gradual clinical improvement was achieved in ali the Condusion: he cu nsidered as recessive in some of the non-progressive ataxic syndromes. are being due to the rarity oflarge pedigrees for genetic studies. Iffurther on and clini cal progression of childhood associated with cerebellar hypoplasia is be a cu mbined of metabolic screening, long-term follow-up and radiological analyses is essential. Key Words: Cerebella r hy poplasia, ataxic syndromes are common during Patients 1 and 2 (first family) childhood. Friedreich 's ataxia and ataxia-telangiectasia Two brothers aged 5 and 7 of unrelated parents arc two best-known examples of such rare syn- presented with a history of slurred speech and diffi- dromes characterized both by their progressive nature culty of gait. -

Cerebellar Atrophy with Long-Term Phenytoin (Pht) Use: Case Report

REVIEWS CASE REPORTS CEREBELLAR ATROPHY WITH LONG-TERM PHENYTOIN (PHT) USE: CASE REPORT Jamir P. Rissardo, Ana L.F. Caprara, Juliana O.F. Silveira Departament of Neurology, Federal University of Santa Maria, RS, Brazil Federal University of Santa Maria Health Sciences Center – Camobi Street, Km 09 – Universitary Campus Santa Maria/RS – 97105-900 ABSTRACT Cerebellar atrophy can be found with long-term phenytoin (PHT) use or acute phenytoin intoxication. PHT may cause cerebellar symptoms, such as nystagmus, diplopia, dysarthria and ataxia. Clinical manifestations may be persistent. We report a case of a 41-year-old male who presented with cerebellar dysfunction and cerebellar atrophy after long- term phenytoin use. He had ataxic gait, preserved strength, commuting deep refl exes, dysmetria, dysdiadochocine- sia, scanning speech and somnolence. Cranial computed tomography revealed enlargement of inter follicular cere- brospinal fl uid spaces in cerebellum and also a slight enlargement of the fourth ventricle, suggesting signs of cerebellar volumetric reduction. PHT was withdrawn. Six months later, he presented improvement in his condition; he had atypical gait, mild dysmetria, diadochokinesia and normal speech. In conclusion, clinicians should be vigilant with patients on phenytoin. If the patient has cerebellar signs with a correspondent clinical history of phenytoin intoxication CT scan should be helpful as an initial cerebellar assessment. Keywords: phenytoin, ataxia, cerebellum, atrophy INTRODUCTION CASE REPORT C erebellar atrophy can be found with long-term A 41-year-old male admitted to our hospital pre- phenytoin (PHT) use (1), acute phenytoin intoxica- senting acute ataxia and scanning speech, for 20 tion (2,9), normal aging brain and alcohol abuse days. -

TWITCH, JERK Or SPASM Movement Disorders Seen in Family Practice

TWITCH, JERK or SPASM Movement Disorders Seen in Family Practice J. Antonelle de Marcaida, M.D. Medical Director Chase Family Movement Disorders Center Hartford HealthCare Ayer Neuroscience Institute DEFINITION OF TERMS • Movement Disorders – neurological syndromes in which there is either an excess of movement or a paucity of voluntary and automatic movements, unrelated to weakness or spasticity • Hyperkinesias – excess of movements • Dyskinesias – unnatural movements • Abnormal Involuntary Movements – non-suppressible or only partially suppressible • Hypokinesia – decreased amplitude of movement • Bradykinesia – slowness of movement • Akinesia – loss of movement CLASSES OF MOVEMENTS • Automatic movements – learned motor behaviors performed without conscious effort, e.g. walking, speaking, swinging of arms while walking • Voluntary movements – intentional (planned or self-initiated) or externally triggered (in response to external stimulus, e.g. turn head toward loud noise, withdraw hand from hot stove) • Semi-voluntary/“unvoluntary” – induced by inner sensory stimulus (e.g. need to stretch body part or scratch an itch) or by an unwanted feeling or compulsion (e.g. compulsive touching, restless legs syndrome) • Involuntary movements – often non-suppressible (hemifacial spasms, myoclonus) or only partially suppressible (tremors, chorea, tics) HYPERKINESIAS: major categories • CHOREA • DYSTONIA • MYOCLONUS • TICS • TREMORS HYPERKINESIAS: subtypes Abdominal dyskinesias Jumpy stumps Akathisic movements Moving toes/fingers Asynergia/ataxia -

Abadie's Sign Abadie's Sign Is the Absence Or Diminution of Pain Sensation When Exerting Deep Pressure on the Achilles Tendo

A.qxd 9/29/05 04:02 PM Page 1 A Abadie’s Sign Abadie’s sign is the absence or diminution of pain sensation when exerting deep pressure on the Achilles tendon by squeezing. This is a frequent finding in the tabes dorsalis variant of neurosyphilis (i.e., with dorsal column disease). Cross References Argyll Robertson pupil Abdominal Paradox - see PARADOXICAL BREATHING Abdominal Reflexes Both superficial and deep abdominal reflexes are described, of which the superficial (cutaneous) reflexes are the more commonly tested in clinical practice. A wooden stick or pin is used to scratch the abdomi- nal wall, from the flank to the midline, parallel to the line of the der- matomal strips, in upper (supraumbilical), middle (umbilical), and lower (infraumbilical) areas. The maneuver is best performed at the end of expiration when the abdominal muscles are relaxed, since the reflexes may be lost with muscle tensing; to avoid this, patients should lie supine with their arms by their sides. Superficial abdominal reflexes are lost in a number of circum- stances: normal old age obesity after abdominal surgery after multiple pregnancies in acute abdominal disorders (Rosenbach’s sign). However, absence of all superficial abdominal reflexes may be of localizing value for corticospinal pathway damage (upper motor neu- rone lesions) above T6. Lesions at or below T10 lead to selective loss of the lower reflexes with the upper and middle reflexes intact, in which case Beevor’s sign may also be present. All abdominal reflexes are preserved with lesions below T12. Abdominal reflexes are said to be lost early in multiple sclerosis, but late in motor neurone disease, an observation of possible clinical use, particularly when differentiating the primary lateral sclerosis vari- ant of motor neurone disease from multiple sclerosis. -

Comprehensive Systematic Review: Treatment of Cerebellar Motor Dysfunction and Ataxia

Comprehensive systematic review: Treatment of cerebellar motor dysfunction and ataxia Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology Theresa A. Zesiewicz, MD1; George Wilmot, MD2; Sheng-Han Kuo, MD3; Susan Perlman, MD4; Patricia E. Greenstein, MB, BCh5; Sarah H. Ying, MD6; Tetsuo Ashizawa, MD7; S.H. Subramony, MD8; Jeremy D. Schmahmann, MD9; K.P. Figueroa10; Hidehiro Mizusawa, MD11; Ludger Schöls, MD12; Jessica D. Shaw, MPH1; Richard M. Dubinsky, MD, MPH13; Melissa J. Armstrong, MD, MSc8; Gary S. Gronseth, MD13; Kelly L. Sullivan, PhD14 1) Department of Neurology, University of South Florida, Tampa 2) Department of Neurology, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 3) Department of Neurology, Columbia University, New York, NY 4) Department of Neurology, University of California, Los Angeles 5) Department of Neurology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA 6) Shire, Lexington, MA, and the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 7) Department of Neurology, Houston Methodist Research Institute, TX 8) Department of Neurology, University of Florida College of Medicine, Gainesville 9) Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 10) Department of Neurology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City 11) National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry, Tokyo, Japan 12) Department of Neurology and Hertie-Institute for Clinical Brain Research, Tübingen, Germany 13) Department of Neurology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City 14) Jiann-Ping Hsu College of Public Health, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro Address correspondence and reprint requests to American Academy of Neurology: [email protected] Title character count: 71 Abstract word count: 254 Manuscript word count: 7,891 Approved by the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee on October 22, 2016; by the Practice Committee on October 2, 2017; and by the AAN Institute Board of Directors on December 5, 2017. -

A Dictionary of Neurological Signs

FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page i A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS SECOND EDITION FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page iii A DICTIONARY OF NEUROLOGICAL SIGNS SECOND EDITION A.J. LARNER MA, MD, MRCP(UK), DHMSA Consultant Neurologist Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Liverpool Honorary Lecturer in Neuroscience, University of Liverpool Society of Apothecaries’ Honorary Lecturer in the History of Medicine, University of Liverpool Liverpool, U.K. FM.qxd 9/28/05 11:10 PM Page iv A.J. Larner, MA, MD, MRCP(UK), DHMSA Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery Liverpool, UK Library of Congress Control Number: 2005927413 ISBN-10: 0-387-26214-8 ISBN-13: 978-0387-26214-7 Printed on acid-free paper. © 2006, 2001 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, Inc., 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dis- similar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to propri- etary rights. While the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of going to press, neither the authors nor the editors nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omis- sions that may be made. -

Ataxia in Children: Early Recognition and Clinical Evaluation Piero Pavone1,6*, Andrea D

Pavone et al. Italian Journal of Pediatrics (2017) 43:6 DOI 10.1186/s13052-016-0325-9 REVIEW Open Access Ataxia in children: early recognition and clinical evaluation Piero Pavone1,6*, Andrea D. Praticò2,3, Vito Pavone4, Riccardo Lubrano5, Raffaele Falsaperla1, Renata Rizzo2 and Martino Ruggieri2 Abstract Background: Ataxia is a sign of different disorders involving any level of the nervous system and consisting of impaired coordination of movement and balance. It is mainly caused by dysfunction of the complex circuitry connecting the basal ganglia, cerebellum and cerebral cortex. A careful history, physical examination and some characteristic maneuvers are useful for the diagnosis of ataxia. Some of the causes of ataxia point toward a benign course, but some cases of ataxia can be severe and particularly frightening. Methods: Here, we describe the primary clinical ways of detecting ataxia, a sign not easily recognizable in children. We also report on the main disorders that cause ataxia in children. Results: The causal events are distinguished and reported according to the course of the disorder: acute, intermittent, chronic-non-progressive and chronic-progressive. Conclusions: Molecular research in the field of ataxia in children is rapidly expanding; on the contrary no similar results have been attained in the field of the treatment since most of the congenital forms remain fully untreatable. Rapid recognition and clinical evaluation of ataxia in children remains of great relevance for therapeutic results and prognostic counseling. Keywords: Ataxia, Diagnostic maneuvers, Acute cerebellitis, Cerebellar syndrome, Cerebellar malformations Background Clinical signs in cerebellar ataxic patients are related to Ataxia in children is a common clinical sign of various impaired localization. -

Full Text (PDF)

RESIDENT & FELLOW SECTION Clinical Reasoning: Section Editor An 82-year-old man with worsening gait John J. Millichap, MD Sheena Chew, MD SECTION 1 neck and left leg cramps. He denied bowel or bladder Ivana Vodopivec, MD, An 82-year-old man with hypothyroidism presented symptoms. PhD with difficulty walking. The patient was previously healthy, playing com- Aaron L. Berkowitz, MD, One year prior to presentation, he noticed that his petitive sports at the national level into his late 70s. PhD legs occasionally “froze” when initiating walking. His His only medication was levothyroxine. gait progressively worsened over the year. He devel- oped balance difficulty, tripping and falling twice Question for consideration: Correspondence to without loss of consciousness. In the 4 months prior Dr. Chew: to presentation, he started using a cane, a rolling 1. What examination findings would help to localize [email protected] walker, then a wheelchair. He reported occasional the etiology of his abnormal gait? GO TO SECTION 2 From the Department of Neurology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital (S.C., I.V., A.L.B.), and Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital (S.C.), Harvard Medical School, Boston. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures. Funding information and disclosures deemed relevant by the authors, if any, are provided at the end of the article. e246 © 2017 American Academy of Neurology ª 2017 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. SECTION 2 arm dysdiadochokinesia and right leg dysmetria, but The neurologic basis of gait spans the entire neuraxis, no left-sided or truncal ataxia. -

Ataxia and Tremor in People with Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

for health professionals Ataxia and tremor in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) Freecall: 1800 042 138 www.msaustralia.org.au MS PRACTICE // ATAXIA AND TREMOR IN PEOPLE WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS Ataxia and tremor in people with multiple sclerosis (MS) Ataxia and tremor are common yet difficult symptoms to manage in people with MS ― often requiring the involvement of a multidisciplinary team. Early intervention is important in order to address both the functional and psychological issues associated with these symptoms. Freecall: 1800 042 138 www.msaustralia.org.au MS PRACTICE // ATAXIA AND TREMOR IN PEOPLE WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS 01 Contents Page 1.0 Definitions 02 2.0 Incidence and impact 3.0 Pathophysiology and clinical characteristics 3.1 Ataxia 3.2 Tremor 03 4.0 Assessment 5.0 Management 04 5.1 Physiotherapy 5.2 Pharmacotherapy 05 5.3 Surgical intervention 06 6.0 Summary Freecall: 1800 042 138 www.msaustralia.org.au MS PRACTICE // AtaXIA AND TREMOR IN PEOPLE WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS 02 1.0 Definitions Ataxia Tremor Ataxia is a term used to describe a number of Tremor is defined as a rhythmic, involuntary, oscillating abnormal movements that may occur during the movement of a body part. There are two main execution of voluntary movements. They include, but classifications of tremor ― resting tremor and action are not limited to, incoordination, delay in movement, tremor. Resting tremor is present in a body part that dysmetria (inaccuracy in achieving a target), is completely supported against gravity and is not dysdiadochokinesia (inability -

Pseudoathetosis in the Spectrum of Alcoholic Neurotoxicity: Presentation and Management

Nachane & Nayak: Pseudoathetosis 154 Case Report Pseudoathetosis in the spectrum of alcoholic neurotoxicity: presentation and management Hrishikesh B. Nachane1, Ajita S. Nayak2 1Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry, T.N.M.C. and B.Y.L. Nair Ch. Hospital, Mumbai 2Professor and Head, Department of Psychiatry, K.E.M. Hospital and Seth G.S. Medical college, Mumbai Corresponding author: Hrishikesh Nachane Email – [email protected] ABSTRACT Pseudoathetosis, a proprioceptive abnormality, refers to a movement disorder consisting of involuntary, slow, writhing movements of the fingers. Although many causes for pseudoathetosis have been documented previously, such as multiple sclerosis, myelitis, leprosy, vitamin B12 deficiency, trauma, etc. it has not been previously described in a case of alcohol use disorder. A 50 years old man with chronic alcoholism presented to us with cognitive impairment, cerebellar signs and slow writhing movements of his fingers. Upon detailed investigations, no vitamin deficiency was detected. The patient was managed with a combination of nutritional supplementation, Memantine and Quetiapine, and had complete reversal of pseudoathetosis. The authors imply that pseudoathetosis can be a presentation of alcoholic neurotoxicity, co-occurring with cortico-cerebellar dysfunction, and can manifest irrespective of nutritional status of the patient. Key words: Pseudoathetosis, alcohol, neurotoxicity (Paper received – 5th January 2020, Peer review completed – 20th February 2020) (Accepted – 28th February 2020) INTRODUCTION With increase in alcohol consumption across India, there has been a steady rise in alcohol related complications [1]. The spectrum of alcoholic neurotoxicity is vast: covering dementia, Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, myelopathy to peripheral neuropathy. These conditions are not only challenging to diagnose, but downright difficult to treat [2].