Apr/May 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TML Propagation Protocols

PROPAGATION PROTOCOLS This document is intended as a guide for Tamborine Mountain Landcare members who wish to assist our regeneration projects by growing some of the plants needed. It is a work in progress so if you have anything to add to the protocols – for example a different but successful way of propagating and growing a particular plant – then please give it to Julie Lake so she can add it to the document. The idea is that our shared knowledge and experience can become a valuable part of TML's intellectual property as well as a useful source of knowledge for members. As there are many hundreds of plants native to Tamborine Mountain, the protocols list will take a long time to complete, with growing information for each plant added alphabetically as time permits. While the list is being compiled by those members with competence in this field, any TML member with a query about propagating a particular plant can post it on the website for other me mb e r s to answer. To date, only protocols for trees and shrubs have been compiled. Vines and ferns will be added later. Fruiting times given are usual for the species but many rainforest plants flower and fruit opportunistically, according to weather and other conditions unknown to us, thus fruit can be produced at any time of year. Finally, if anyone would like a copy of the protocols, contact Julie on [email protected] and she’ll send you one. ………………….. Growing from seed This is the best method for most plants destined for regeneration projects for it is usually fast, easy and ensures genetic diversity in the regenerated landscape. -

Diet of the White-Headed Pigeon Columba Leucomela Near Lismore, Northern New South Wales: Fruit, Seeds, Flower Buds, Bark and Grit

Corella, 2011, 35(3): 107-111 Diet of the White-headed Pigeon Columba leucomela near Lismore, northern New South Wales: fruit, seeds, flower buds, bark and grit D. G. Gosper 39 Azure Avenue, Balnarring, Victoria 3926, Australia Received: 27 May 2010 Gut contents of 18 White-headed Pigeons Columba leucomela, found dead over a four-year period near Lismore in northern New South Wales, comprised fruits and seeds of the invasive plant Camphor Laurel Cinnamomum camphora almost exclusively. Birds frequently ingested Melaleuca quinquenervia bark, which, as far as I am aware, constitutes the fi rst record of consumption of bark in the Columbidae, prompting some interesting hypotheses. It is suggested that bark ingestion may counter potential adverse effects from a diet dominated by Camphor Laurel fruits and seeds, which are reputed to contain toxins. Incidental records of consumption of fl ower buds of indigenous plants and insects (the fi rst such records for this species), and regular drinking from man-made structures such as roof guttering on buildings are detailed. INTRODUCTION surrounding area is a mixture of pasture, remnant riparian rainforest and regrowth forest with extensive areas dominated The White-headed Pigeon Columba leucomela is known to by woody weed species, notably Camphor Laurel and Broad- feed on the fruits and seeds of a number of fl eshy-fruited invasive leaved Privet Ligustrum lucidum, and several house gardens. plants, notably Camphor Laurel Cinnamomum camphora, which has become an important seasonal food source for this species Dead pigeons were collected and crop and gizzard contents in northern New South Wales (NSW) (Frith 1982; Recher and removed during subsequent dissection. -

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan

Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan Working Plan for Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3 Upper North East Forest Agreement Region North East Region Contents Page 1. DETAILS OF THE RESERVE 2 1.1 Introduction 2 1.2 Location 2 1.3 Key Attributes of the Reserve 2 1.4 General Description 2 1.5 History 6 1.6 Current Usage 8 2. SYSTEM OF MANAGEMENT 9 2.1 Objectives of Management 9 2.2 Management Strategies 9 2.3 Management Responsibility 11 2.4 Monitoring, Reporting and Review 11 3. LIST OF APPENDICES 11 Appendix 1 Map 1 Locality Appendix 1 Map 2 Cadastral Boundaries, Forest Types and Streams Appendix 1 Map 3 Vegetation Growth Stages Appendix 1 Map 4 Existing Occupation Permits and Recreation Facilities Appendix 2 Flora Species known to occur in the Reserve Appendix 3 Fauna records within the Reserve Y:\Tourism and Partnerships\Recreation Areas\Orara East SF\Bruxner Flora Reserve\FlRWP_Bruxner.docx 1 Bruxner Park Flora Reserve Working Plan 1. Details of the Reserve 1.1 Introduction This plan has been prepared as a supplementary plan under the Nature Conservation Strategy of the Upper North East Ecologically Sustainable Forest Management (ESFM) Plan. It is prepared in accordance with the terms of section 25A (5) of the Forestry Act 1916 with the objective to provide for the future management of that part of Orara East State Forest No 536 set aside as Bruxner Park Flora Reserve No 3. The plan was approved by the Minister for Forests on 16.5.2011 and will be reviewed in 2021. -

Fig Parrot Husbandry

Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author AVIAN HUSBANDRY NOTES FIG PARROTS MACLEAY’S FIG PARROT Cyclopsitta diopthalma macleayana BAND SIZE AND SPECIAL BANDING REQUIREMENTS - Band size 3/16” - Donna Corporation Band Bands must be metal as fig parrots are vigorous chewers and will destroy bands made of softer material. SEXING METHODS - Fig Parrots can be sexed visually, when mature (approximately 1 year). Males - Lower cheeks and centre of forehead red; remainder of facial area blue, darker on sides of forehead, paler and more greenish around eyes. Females - General plumage duller and more yellowish than male; centre of forehead red; lower cheeks buff - brown with bluish markings; larger size (Forshaw,1992). ADULT WEIGHTS AND MEASUREMENTS - Male - Wing: 83-90 mm Tail : 34-45 mm Exp. cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g Female - Wing: 79-89 mm Tail: 34-45 mm Exp.cul: 13-14 mm Tars: 13-14 mm Weight : 39-43 g (Crome & Shield, 1992) Orange-breasted Fig Parrot Cyclopsitta gulielmitertii Edwards Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris edwardsii Salvadori’s Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris salvadorii Desmarest Fig Parrot Psittaculirostris desmarestii Fig Parrot Husbandry Manual – Draft September2000 Compiled by Liz Romer 1 Made available at http://www.aszk.org.au/Husbandry%20Manuals.htm with permission of the author NATURAL HISTORY Macleay’s Fig Parrot 1.0 DISTRIBUTION Macleay’s Fig Parrot inhabits coastal and contiguous mountain rainforests of north - eastern Queensland, from Mount Amos, near Cooktown, south to Cardwell, and possibly the Seaview Range. This subspecies is particularly common in the Atherton Tableland region and near Cairns where it visits fig trees in and around the town to feed during the breeding season (Forshaw,1992). -

Ficus Rubiginosa 1 (X /2)

KEY TO GROUP 4 Plants with a milky white sap present – latex. Although not all are poisonous, all should be treated with caution, at least initially. (May need to squeeze the broken end of the stem or petiole). The plants in this group belong to the Apocynaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Moraceae, and Sapotaceae. Although an occasional vine in the Convolvulaceae which, has some watery/milky sap will key to here, please refer to Group 3. (3.I, 3.J, 3.K) A. leaves B. leaves C. leaves alternate opposite whorled 1 Leaves alternate on the twigs (see sketch A), usually shrubs and 2 trees, occasionally a woody vine or scrambler go to Group 4.A 1* Leaves opposite (B) or whorled (C), i.e., more than 2 arising at the same level on the twigs go to 2 2 Herbs usually less than 60 cm tall go to Group 4.B 2* Shrubs or trees usually taller than 1 m go to Group 4.C 1 (All Apocynaceae) Ficus obliqua 1 (x /2) Ficus rubiginosa 1 (x /2) 2 GROUP 4.A Leaves alternate, shrubs or trees, occasional vine (chiefly Moraceae, Sapotaceae). Ficus spp. (Moraceae) Ficus, the Latin word for the edible fig. About 9 species have been recorded for the Island. Most, unless cultivated, will be found only in the dry rainforest areas or closed forest, as in Nelly Bay. They are distinguished by the latex which flows from all broken portions; the alternate usually leathery leaves; the prominent stipule (↑) which encloses the terminal bud and the “fig” (↑) or syconia. This fleshy receptacle bears the flowers on the inside; as the seeds mature the receptacle enlarges and often softens (Think of the edible fig!). -

Flying Foxes Jerry Copy

Species Common Name Habit Flowering Fruit Notes Acacia macradenia Zigzag wattle Shrub August Possible pollen source Albizia lebbek Lebbek Tall tree summer Source of nectar. Excellent shade tree for large gardens. Alphitonia excelsa Red ash Tree October to March November to May Food source for Black and Grey- headed flying fox Angophora costata Smooth-barked Tall tree December to Source of nectar apple January Angophora Rough-barked apple Tall tree September to Source of nectar floribunda February Angophora costata Smooth-barked Tall tree November to Source of nectar subsp. leiocarpa apple, Rusty gum February Archontophoenix Alexander palm Tree-like November to January Food source for alexandrae December Spectacled flying fox. Good garden tree Archontophoenix Bangalow palm Tree-like February to June March to July Food source for cunninghamiana Grey-headed flying fox. Good garden tree Species Common Name Habit Flowering Fruit Notes Banksia integrifolia Coastal Shrub or small tree Recurrent, all year Food source for honeysuckle round Black and Grey- headed flying fox. Good garden tree Banksia serrata Old man banksia Shrub or small tree February to May Source of nectar. Good garden tree Buckinghamia Ivory curl tree Small tree December to Possible source of celsissima February nectar. Good garden tree Callistemon citrinus Crimson bottlebrush Shrub or small tree November and Source of nectar. March Good garden tree Callistemon salignus White bottlebrush Shrub or small tree spring Source of nectar. Good garden tree Castanospermum Moreton Bay Tall tree spring Source of nectar australe chestnut, Black bean Corymbia citriodora Lemon-scented gum Tall tree may flower in any Source of nectar season Corymbia Red bloodwood From mallee to tall summer to autumn Source of nectar gummifera tree Corymbia Pink bloodwood Tall tree December to March Source of nectar. -

Pollinated by Pleistodontes Imperialis. (Ficus Carica); Most

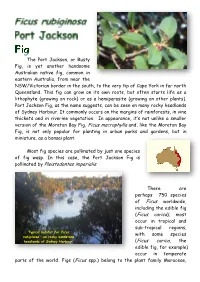

The Port Jackson, or Rusty Fig, is yet another handsome Australian native fig, common in eastern Australia, from near the NSW/Victorian border in the south, to the very tip of Cape York in far north Queensland. This fig can grow on its own roots, but often starts life as a lithophyte (growing on rock) or as a hemiparasite (growing on other plants). Port Jackson Fig, as the name suggests, can be seen on many rocky headlands of Sydney Harbour. It commonly occurs on the margins of rainforests, in vine thickets and in riverine vegetation. In appearance, it’s not unlike a smaller version of the Moreton Bay Fig, Ficus macrophylla and, like the Moreton Bay Fig, is not only popular for planting in urban parks and gardens, but in miniature, as a bonsai plant. Most fig species are pollinated by just one species of fig wasp. In this case, the Port Jackson Fig is pollinated by Pleistodontes imperialis. There are perhaps 750 species of Ficus worldwide, including the edible fig (Ficus carica); most occur in tropical and sub-tropical regions, Typical habitat for Ficus with some species rubiginosa – on rocky sandstone headlands of Sydney Harbour. (Ficus carica, the edible fig, for example) occur in temperate parts of the world. Figs (Ficus spp.) belong to the plant family Moraceae, which also includes Mulberries (Morus spp.), Breadfruit and Jackfruit (Artocarpus spp.). Think of a mulberry, and imagine it turned inside out. This might perhaps bear some resemblance to a fig. Ficus rubiginosa growing on a sandstone platform adjoining mangroves. Branches of one can be seen in the foreground, a larger one at the rear. -

Ficus Rubiginosa F. Rubiginosa Click on Images to Enlarge

Species information Abo ut Reso urces Hom e A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Ficus rubiginosa f. rubiginosa Click on images to enlarge Family Moraceae Scientific Name Ficus rubiginosa Desf. ex Vent. f. rubiginosa Ventenat, E.P. (1805) Jard. Malm. : 114. Type: New Holland; holo: FI. Fide Dixon et al. (2001). Leaves and figs. Copyright G. Sankowsky Common name Fig; Small-leaved Fig; Larger Small-leaved Fig; Larger Small Leaf Fig; Fig, Larger Small Leaf; Fig, Small-leaved Stem A strangling fig, hemi-epiphyte or lithophyte to 30 m. Leaves Figs. Copyright G. Sankowsky Petioles and twigs produce a milky exudate. Stipules about 2-6 cm long, usually smooth on the outer surface, occasionally hairy. Petioles to 4 cm long, channelled on the upper surface. Leaf blades rather variable in shape, about 6-10 x 2-3 cm; leaves hairy. Flowers Tepals glabrous. Male flowers dispersed among the fruitlets in the ripe figs. Anthers reniform. Stigma cylindric, papillose, often slightly coiled. Bracts at the base of the fig, two. Lateral bracts not present on the outside of the fig body. Fruit Scale bar 10mm. Copyright CSIRO Figs pedunculate, globose, about 10-18 mm diam. Orifice triradiate, +/- closed by inflexed internal bracts. Seedlings Cotyledons ovate-oblong, about 5 mm long. At the tenth leaf stage: leaves ovate, apex acute or bluntly acute, base obtuse or cordate, margin entire, glabrous, somewhat triplinerved at the base; oil dots not visible; stipules large, sheathing the terminal bud, about 20-40 mm long. -

![12 Laman St Figs Report 280910[1] Mckenzie](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3219/12-laman-st-figs-report-280910-1-mckenzie-1293219.webp)

12 Laman St Figs Report 280910[1] Mckenzie

Expert Witness Report Parks and Playgrounds Movement Inc v Newcastle City Council [2010] NSWLEC 40745 Laman Street, Cooks Hill (between Dawson Street and Darby Street) Prepared for Parks and Playgrounds Movement Inc (Contact: Mr Doug Lithgow, President) Prepared by Ian McKenzie – Consulting Arborist 28 September 2010 Table of Contents 1 Summary.....................................................................................................2 2 Introduction ................................................................................................4 2.1 Acknowledgement ................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Disclaimer ................................................................................................................ 4 2.3 Background .............................................................................................................. 4 2.4 Brief ......................................................................................................................... 5 2.5 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 6 3 Site Details..................................................................................................7 3.1 Site Description........................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Heritage Status ........................................................................................................ -

Interactions Among Leaf Miners, Host Plants and Parasitoids in Australian Subtropical Rainforest

Food Webs along Elevational Gradients: Interactions among Leaf Miners, Host Plants and Parasitoids in Australian Subtropical Rainforest Author Maunsell, Sarah Published 2014 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith School of Environment DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/3017 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/368145 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Food webs along elevational gradients: interactions among leaf miners, host plants and parasitoids in Australian subtropical rainforest Sarah Maunsell BSc (Hons) Griffith School of Environment Science, Environment, Engineering and Technology Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy February 2014 Synopsis Gradients in elevation are used to understand how species respond to changes in local climatic conditions and are therefore a powerful tool for predicting how mountain ecosystems may respond to climate change. While many studies have shown elevational patterns in species richness and species turnover, little is known about how multi- species interactions respond to elevation. An understanding of how species interactions are affected by current clines in climate is imperative if we are to make predictions about how ecosystem function and stability will be affected by climate change. This challenge has been addressed here by focussing on a set of intimately interacting species: leaf-mining insects, their host plants and their parasitoid predators. Herbivorous insects, including leaf miners, and their host plants and parasitoids interact in diverse and complex ways, but relatively little is known about how the nature and strengths of these interactions change along climatic gradients. -

Atoll Research Bulletin No. 350 Pisonia Islands of the Great Barrier Reef

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN NO. 350 PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PART I. THE DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE AND DISPERSAL BY SEABIRDS OF PISONIA GRANDIS BY T. A. WALKER PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PARTII. THE VASCULAR FLORAS OF BUSHY AND REDBILL ISLANDS BY T. A. WALKER, M.Y. CHALOUPKA, AND B. R KING. PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PART 111. CHANGES IN THE VASCULAR FLORA OF LADY MUSGRAVE ISLAND BY T. A. WALKER ISSUED BY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON D.C., U.S.A. JULY 1991 (60 mme gauge) (104 mwe peak) Figure 1-1. The Great Barrier Reef showing localities referred to in the text. Mean monthly rainfall data is illustrated for the four cays and the four rocky islands where records are available. Sizes of the ten largest cays on the Great Barrier Reef are shown below - three at the southern end (23 -24s) and seven at the northern end (9-11s). 4m - SEA LidIsland 14 years (1973-1986) 'J . armual mean 15% mm 1m annual median 1459 mm O ' ONDMJJAS (10 metre gauge) "A (341 mme peak) Low Islet 97 yeam (1887-1984) annualmeana080mm 100 . annual median 2038 mm $> .:+.:.:. n8 m 100 Pine Islet 52 yeus (1934-1986) &al mean 878 mm. malmedm 814 mm (58 mwe hgh puge. 68 mem iddpeak) O ONDJFIVlnJJAS MO Nonh Reef Island l6years (1961-1977) mual mean 1067 mm. mmlmedian 1013 mm O ONDMJJAS MO Haon Island 26 years (19561982) annual mean 1039 mm,mal median 1026 mm Lady Elliot Island 47 yeus (1539-1986) annual mean 1177 mm, ma1median 1149 mm O ONDMJJAS PISONIA ISLANDS OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF PART I. -

I Is the Sunda-Sahul Floristic Exchange Ongoing?

Is the Sunda-Sahul floristic exchange ongoing? A study of distributions, functional traits, climate and landscape genomics to investigate the invasion in Australian rainforests By Jia-Yee Samantha Yap Bachelor of Biotechnology Hons. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2018 Queensland Alliance for Agriculture and Food Innovation i Abstract Australian rainforests are of mixed biogeographical histories, resulting from the collision between Sahul (Australia) and Sunda shelves that led to extensive immigration of rainforest lineages with Sunda ancestry to Australia. Although comprehensive fossil records and molecular phylogenies distinguish between the Sunda and Sahul floristic elements, species distributions, functional traits or landscape dynamics have not been used to distinguish between the two elements in the Australian rainforest flora. The overall aim of this study was to investigate both Sunda and Sahul components in the Australian rainforest flora by (1) exploring their continental-wide distributional patterns and observing how functional characteristics and environmental preferences determine these patterns, (2) investigating continental-wide genomic diversities and distances of multiple species and measuring local species accumulation rates across multiple sites to observe whether past biotic exchange left detectable and consistent patterns in the rainforest flora, (3) coupling genomic data and species distribution models of lineages of known Sunda and Sahul ancestry to examine landscape-level dynamics and habitat preferences to relate to the impact of historical processes. First, the continental distributions of rainforest woody representatives that could be ascribed to Sahul (795 species) and Sunda origins (604 species) and their dispersal and persistence characteristics and key functional characteristics (leaf size, fruit size, wood density and maximum height at maturity) of were compared.