Correlations Between Multiple Tracers of the Cosmic Web Arxiv

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Nonstandard Signals in Cosmological Data †

Proceeding Paper An Overview of Nonstandard Signals in Cosmological Data † George Alestas ‡,* , George V. Kraniotis ‡ and Leandros Perivolaropoulos ‡ Division of Theoretical Physics, University of Ioannina, 45110 Ioannina, Greece; [email protected] (G.V.K.); [email protected] (L.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] † Presented at the 1st Electronic Conference on Universe, 22–28 February 2021; Available online: https://ecu2021.sciforum.net/. ‡ Current address: Department of Physics, University of Ioannina, 45110 Ioannina, Greece. Abstract: We discuss in a unified manner many existing signals in cosmological and astrophysical data that appear to be in some tension (2s or larger) with the standard LCDM as defined by the Planck18 parameter values. The well known tensions of LCDM include the H0 tension the S8 tension and the lensing (Alens) CMB anomaly. There is however, a wide range of other, less standard signals towards new physics. Such signals include, hints for a closed universe in the CMB, the cold spot anomaly indicating non-Gaussian fluctuations in the CMB, the hemispherical temperature variance assymetry and other CMB anomalies, cosmic dipoles challenging the cosmological principle, the Lyman-a forest Baryon Accoustic Oscillation anomaly, the cosmic birefringence in the CMB, the Lithium problem, oscillating force signals in short range gravity experiments etc. In this contribution present the current status of many such signals emphasizing their level of significance and referring to recent resources where more details can be found for each signal. We also briefly mention some possible generic theoretical approaches that can collectively explain the non-standard nature of these signals. In many cases, the signals presented are controversial and there is currently debate in the literature on the possible systematic origin of some of these signals. -

Finite Cosmology and a CMB Cold Spot

SLAC-PUB-11778 gr-qc/0602102 Finite cosmology and a CMB cold spot Ronald J. Adler,∗ James D. Bjorken† and James M. Overduin∗ ∗Gravity Probe B, Hansen Experimental Physics Laboratory, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, U.S.A. †Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94309, U.S.A. The standard cosmological model posits a spatially flat universe of infinite extent. However, no observation, even in principle, could verify that the matter extends to infinity. In this work we model the universe as a finite spherical ball of dust and dark energy, and obtain a lower limit estimate of its mass and present size: the mass 23 is at least 5 10 M⊙ and the present radius is at least 50 Gly. If we are not too far × from the dust-ball edge we might expect to see a cold spot in the cosmic microwave background, and there might be suppression of the low multipoles in the angular power spectrum. Thus the model may be testable, at least in principle. We also obtain and discuss the geometry exterior to the dust ball; it is Schwarzschild-de Sitter with a naked singularity, and provides an interesting picture of cosmogenesis. Finally we briefly sketch how radiation and inflation eras may be incorporated into the model. 1 Introduction The standard or “concordance” model of the present universe has been very successful in that it is consistent with a wide and diverse array of cosmological data. The model posits a spatially flat (k = 0) Friedmann-Robertson-Walker (FRW) universe of infinite extent, filled with dark energy, well described by a cosmological constant, and pressureless cold dark matter or “dust.” Despite the phenomenological success of the model, our present ignorance of the physical nature of both the dark energy and dark matter should prevent us from being complacent. -

On the Evolution of Large-Scale Structure in a Cosmic Void

On the Evolution of Large-Scale Structure in a Cosmic Void Town Sean Philip February Cape of Thesis Presented for the Degree of UniversityDoctor of Philosophy in the Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics University of Cape Town February 2014 Supervised by Assoc. Prof. Chris A. Clarkson & Prof. George F. R. Ellis The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University ii Contents Declaration vii Abstract ix Acknowledgements xi Conventions and Acronyms xiii 1 The Standard Model of Cosmology 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.1.1 Historical Overview 1 1.1.2 The Copernican Principle 5 1.2 Theoretical Foundations 10 1.2.1 General Relativity 10 1.2.2 Background Dynamics 10 1.2.3 Redshift, Cosmic Age and distances 13 1.2.4 Growth of Large-Scale Structure 16 1.3 Observational Constraints 23 1.3.1 Overview 23 1.3.2 A Closer Look at the BAO 27 iii 1.4 Challenges, and Steps Beyond 31 2 Lemaˆıtre-Tolman-Bondi Cosmology 35 2.1 Motivation and Review 35 2.2 Background Dynamics 37 2.2.1 Metric and field equations 37 2.2.2 Determining the solution 40 2.2.3 Connecting to observables 41 2.3 Linear Perturbation Theory in LTB 46 2.3.1 Introduction 46 2.3.2 Defining the perturbations 47 2.3.3 Einstein equations 57 2.3.4 The homogeneous -

The Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation at Large Scales and the Peak Theory

UNIVERSIDAD DE CANTABRIA La radiaci´ondel fondo c´osmicode microondas a gran escala y la teor´ıade picos por Airam Marcos Caballero Memoria presentada para optar al t´ıtulode Doctor en Ciencias F´ısicas en el Instituto de F´ısicade Cantabria Abril 2017 Declaraci´onde Autor´ıa Enrique Mart´ınezGonz´alez, doctor en ciencias f´ısicasy profesor de investigaci´ondel Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cient´ıficas, y Patricio Vielva Mart´ınez, doctor en ciencias f´ısicasy profesor contratado doctor de la Universidad de Cantabria, CERTIFICAN que la presente memoria, La radiaci´ondel fondo c´osmicode microondas a gran scala y la teor´ıade picos ha sido realizada por Airam Marcos Caballero bajo nuestra direcci´onen el Instituto de F´ısicade Cantabr´ıa,para optar al t´ıtulode Doctor por la Universidad de Cantabria. Consideramos que esta memoria contiene aportaciones cient´ıficassuficientes para cons- tituir la Tesis Doctoral del interesado. En Santander, a 7 de abril de 2017, Enrique Mart´ınezGonz´alez Patricio Vielva Mart´ınez iii Agradecimientos Ciertamente, esta tesis no podr´ıahaber sido posible sin la ayuda, apoyo, trabajo y con- sejos de mis dos directores, Enrique y Patricio. Gracias a ellos he podido adentrarme en el mundo de la cosmolog´ıa,incluso en regiones que van mucho m´asall´ade lo presentado en esta tesis. Muchas gracias por todo este tiempo en el que no he dejado de aprender. No ser´ıajusto empezar estos agradecimientos sin mencionar tambi´ena los organismos que me han dado cobijo y apoyo econ´omico: el Instituto de F´ısica de Cantabria, la Universidad de Cantabria, el Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cient´ıficasy el Minis- terio de Econom´ıay Competitividad. -

Light Propagation and Observations in Inhomogeneous Cosmological Models

HELSINKI INSTITUTE OF PHYSICS INTERNAL REPORT SERIES HIP-2015-03 Light Propagation and Observations in Inhomogeneous Cosmological Models Mikko Lavinto Helsinki Institute of Physics University of Helsinki Finland ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented with the permission of the Faculty of Science of the University of Helsinki for public criticism in the auditorium D101 of Physicum, Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2a, on the 27th of November 2015 at 12 o’clock. Helsinki 2015 ISBN 978-951-51-1261-3 (printed) ISBN 978-951-51-1262-0 (electronic) ISSN 1455-0563 http://ethesis.helsinki.fi Unigrafia Helsinki 2015 i Abstract The science of cosmology relies heavily on interpreting observations in the context of a theoretical model. If the model does not capture all of the relevant physical effects, the interpretation of observations is on shaky grounds. The concordance model in cosmology is based on the homogeneous and isotropic Friedmann-Robertson-Walker metric with small perturbations. One long standing question is whether the small-scale details of the matter distribution can modify the predictions of the concordance model, or whether the concordance model can describe the universe to a high precision. In this thesis, I discuss some potential ways in which inhomogeneities may change the in- terpretation of observations from the predictions of the concordance model. One possibility is that the small-scale structure affects the average expansion rate of the universe via a process called backreaction. In such a case the concordance model fails to describe the time-evolution of the universe accurately, leading to the mis-interpretation of observations. Another possibility is that the paths that light rays travel on are curved in such a way that they do not cross all regions with equal probability. -

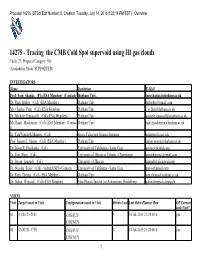

14275 (Stsci Edit Number: 0, Created: Tuesday, July 14, 2015 8:28:14 PM EST) - Overview

Proposal 14275 (STScI Edit Number: 0, Created: Tuesday, July 14, 2015 8:28:14 PM EST) - Overview 14275 - Tracing the CMB Cold Spot supervoid using HI gas clouds Cycle: 23, Proposal Category: GO (Availability Mode: SUPPORTED) INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Prof. Tom Shanks (PI) (ESA Member) (Contact) Durham Univ. [email protected] Dr. Rich Bielby (CoI) (ESA Member) Durham Univ. [email protected] Mr. Charles Finn (CoI) (ESA Member) Durham Univ. [email protected] Dr. Michele Fumagalli (CoI) (ESA Member) Durham Univ. [email protected] Mr. Ruari Mackenzie (CoI) (ESA Member) (Contac Durham Univ. [email protected] t) Dr. TalaWanda R Monroe (CoI) Space Telescope Science Institute [email protected] Prof. Simon L. Morris (CoI) (ESA Member) Durham Univ. [email protected] Dr. Jason X. Prochaska (CoI) University of California - Santa Cruz [email protected] Dr. Yue Shen (CoI) University of Illinois at Urbana - Champaign [email protected] Dr. Istvan Szapudi (CoI) University of Hawaii [email protected] Dr. Nicolas Tejos (CoI) (AdminUSPI) (Contact) University of California - Santa Cruz [email protected] Dr. Tom Theuns (CoI) (ESA Member) Durham Univ. [email protected] Dr. Gabor Worseck (CoI) (ESA Member) Max-Planck-Institut fur Astronomie, Heidelberg [email protected] VISITS Visit Targets used in Visit Configurations used in Visit Orbits Used Last Orbit Planner Run OP Current with Visit? 01 (1) J0315-2143 COS/FUV 3 14-Jul-2015 21:28:03.0 yes COS/NUV 02 (2) J0321-1758 COS/FUV 4 14-Jul-2015 21:28:06.0 yes COS/NUV 1 Proposal 14275 (STScI Edit Number: 0, Created: Tuesday, July 14, 2015 8:28:14 PM EST) - Overview Visit Targets used in Visit Configurations used in Visit Orbits Used Last Orbit Planner Run OP Current with Visit? 03 (2) J0321-1758 COS/FUV 2 14-Jul-2015 21:28:09.0 yes COS/NUV 04 (3) J0317-1654 COS/FUV 3 14-Jul-2015 21:28:11.0 yes COS/NUV 05 (4) J0326-1646 COS/FUV 3 14-Jul-2015 21:28:13.0 yes COS/NUV 15 Total Orbits Used ABSTRACT The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) Cold Spot, a ~100 sq. -

Cosmic Homogeneity As Standard Ruler Pierros Ntelis

Cosmic Homogeneity as standard ruler Pierros Ntelis Collaborators: J. Rich .97 J.C. Hamilton )=2 H ( J.M. Le Goff 2 R A.Ealet D S. Escoffier A.J. Hawken A. Tilquin Post Doc Aix-Marseille University, CPPM P. Ntelis 2nd Colloque National DE, October 2018 s. 1 Cosmic Homogeneity as standard ruler What can fractality tell us about the universe? Romansco Broccoli, Italy since 16th c. ) Simulation (<r Angulo et al (2008) N r ln ln d d )= Euclid (r 2 eBOSS LSST DESI D P. Ntelis 2nd Colloque National DE, October 2018 s. 2 Cosmic Homogeneity as standard ruler Outline ΛCDM Phenomenology Challenges of Cosmological Principle Standard Rulers and Candles Homogeneity scale as a standard Ruler Conclusion and Outlook P. Ntelis 2nd Colloque National DE, October 2018 s. 3 Cosmic Homogeneity as standard ruler Statistical On enough Standard Homogeneity Cosmological Principle = large Phenomenology ΛCDM + scales Isotropy Non Homogeneous + Isotropic Homogeneous + Isotropic M.Stolpovskiy P. Ntelis 2nd Colloque National DE, October 2018 s. 4 Cosmic Homogeneity as standard ruler Standard 4 4 R Least EH = c d xp g Phenomenology ΛCDM S − 16⇡G Action Z Principle Gµ⌫ Tµ⌫ Metric Ansatz / Perturbed g g¯ + δg Einstein-Boltzmann µ⌫ ' µ⌫ µ⌫ Equations + X, Cosmic Components, (b,CDM,DE,…) δf (~x, p,~ t)= [δf (~x, p,~ t)] Dt X C X 8 coupled non linear differential P. Ntelis 2nd Colloque National DE, October 2018 s. 5 Cosmic Homogeneity as standard ruler 5 % 26 % 69 % Perturbed Planck SDSS 2018 ++ Equations Boltzmann-Einstein Cosmological Principle Homogeneous + Isotropic P. Ntelis 2nd Colloque National DE, October 2018 s. -

Universe Secrets Exposed

Universe Secrets Exposed 1/1/11 Universe Secrets Exposed using NASA’s and Other Equivalent Data Sub title Universe Center Found by triangulation of Hubble Deep Fields and the CMB cold spots by Charles Sven 1/1/11 June 13, 2006 contents • Secrets are unassembled NASA data • CMB or Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation embers are radiating across 13.7 billion light years to earth from every direction • Very slow Earth moves at 600k/s or 0.2% of the speed of light • Hubble Space Telescope Deep Fields • coldest CMB embers found in Eridanus • Triangulation locates center • Conclusion Universe Secrets Exposed • NASA’s data (via triangulation) supports Earth next to the epicenter of the Big Bang. • This explosion converted dark energy into matter (as was demonstrated at Stanford Lab.) • Fastest stuff out took 14+ billion years •(That CMB ember radiation) took another 13.7 billion years to shine back to earth as well in all directions - A 28 billion year round trip. Universe Secrets Exposed • NASA’s data (via triangulation) supports Earth next to the epicenter of the Big Bang. • This explosion converted dark energy into matter (as was demonstrated at Stanford Lab.) • Fastest stuff out took 14+ billion years •(That CMB ember radiation) took another 13.7 billion years to shine back to earth as well in all directions - A 28 billion year round trip. E=mc 2 and the Reverse High Energy Beam Matter created from energy at Stanford Linear Accelerator. Reported 9/1/97 High Energy Laser Universe Secrets Exposed • NASA’s data (via triangulation) supports Earth next to the epicenter of the Big Bang. -

CMB Cold Spot from Inflationary Feature Scattering

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Nuclear Physics B 906 (2016) 367–380 www.elsevier.com/locate/nuclphysb CMB cold spot from inflationary feature scattering ∗ Yi Wang a,b, Yin-Zhe Ma c,d, a Department of Physics, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Clear Water Bay, Kowloon, Hong Kong, PR China b Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0WA, UK c School of Chemistry and Physics, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Westville Campus, Private Bag X54001, Durban, 4000, South Africa d Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK Received 4 July 2015; received in revised form 8 March 2016; accepted 15 March 2016 Available online 21 March 2016 Editor: Hong-Jian He Abstract We propose a “feature-scattering” mechanism to explain the cosmic microwave background cold spot seen from WMAP and Planck maps. If there are hidden features in the potential of multi-field inflation, the inflationary trajectory can be scattered by such features. The scattering is controlled by the amount of isocurvature fluctuations, and thus can be considered as a mechanism to convert isocurvature fluctuations into curvature fluctuations. This mechanism predicts localized cold spots (instead of hot ones) on the CMB. In addition, it may also bridge a connection between the cold spot and a dip on the CMB power spectrum at ∼ 20. © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). -

Cosmic Microwave Background

Christian: Cosmic Microwave Background April 17, 2020 Monday, April 13, 2020 Christian final report: Cosmic Microwave Background Cosmic Microwave Background Hey everyone, here is my presentation on the early universe. Will try to answer any questions asap. Adam Q & A: Q Clayton: Good presentation Christian. On slide 13 you mention that an increase in baryons and and photons would mean a decrease in neutrons, does this happen because the neutrons decay into a baryons and photons, or is there another process that happen to cause these increases and decreases? A Christian: The fundamental difference between isocurvature and adiabatic perturbation is that isocurva- ture perturbations maintain a homogeneous density, and the perturbations are only related to entropy, while adiabatic perturbations induce inhomogeneities in the spatial curvature. I believe that you’re right in saying that a neutron decaying into a photon and proton would maintain the criteria for an isocurvature perturbation, but I’m sure there are other weak interactions that would also. Q Noah: Great presentation, Christian! I have some questions regarding slide 17. Are there cold spots in the CMB that are not caused by the presence of large voids? If so, what is attributed to be their source? Also, are there hot spots in the CMB? A Christian: The difficult thing about cold spots is that we’re not actually sure where they come from. Some studies indicate voids and smaller galaxy concentrations in the WMAP Cold Spot (the main CMB Cold Spot), but different surveys conflict with this observation, and it is generally accepted that the void necessary to explain such an anomoly would be exceptionally large, 3 orders of magnitude larger in volume than typical voids. -

Cosmic Troublemakers: the Cold Spot, the Eridanus Supervoid, and the Great Walls

MNRAS 000,1{ ?? (2015) Preprint 19 July 2016 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Cosmic troublemakers: the Cold Spot, the Eridanus Supervoid, and the Great Walls Andr´as Kov´acs1?, Juan Garc´ıa-Bellido2y, 1 Institut de F´ısica d'Altes Energies, The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, E-08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain 2 Instituto de F´ısica Te´orica IFT-UAM/CSIC, Universidad Aut´onoma de Madrid, Cantoblanco 28049 Madrid, Spain Submitted 2015 ABSTRACT The alignment of the CMB Cold Spot and the Eridanus supervoid suggests a physi- cal connection between these two relatively rare objects. We use galaxy catalogues with photometric (2MPZ) and spectroscopic (6dF) redshift measurements, supplemented by low-redshift compilations of cosmic voids, in order to improve the 3D mapping of the matter density in the Eridanus constellation. We find evidence for a supervoid with a significant elongation in the line-of-sight, effectively spanning the total red- shift range z < 0:3. Our tomographic imaging reveals important substructure in the Eridanus supervoid, with a potential interpretation of a long, fully connected system of voids. We improve the analysis by extending the line-of-sight measurements into the antipodal direction that interestingly crosses the Northern Local Supervoid at the lowest redshifts. Then it intersects very rich superclusters like Hercules and Corona Borealis, in the region of the Coma and Sloan Great Walls, as a possible compensation for the large-scale matter deficit of Eridanus. We find that large-scale structure mea- surements are consistent with a central matter underdensity δ0 ≈ −0:25, projected ? transverse radius r0 ≈ 195 Mpc/h with an extra deepening in the centre, and line- k of-sight radius r0 ≈ 500 Mpc/h, i.e. -

Hsw Void As the Origin of Cold Spot

Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. Vol. 23 No. 4; October – December 2016 85 Suranaree J. Sci. Technol. Vol. 23 No. 4; October - December 2016 435 HSW VOID AS THE ORIGIN OF COLD SPOT Anut Sangka1,2 , Utane Sawangwit2, Nuanwan Sanguansak1, and 3 Teeraparb Chantavat∗ Received: September 09, 2016; Revised: November 28, 2016; Accepted: December 01, 2016 Abstract The cosmic microwave background (CMB) cold spot (CS) anomaly is one of the most important unresolved issues in CMB observations. The CS has an angular radius in the o sky greater than 5 and a temperature at the centre of about 160 μK which is lower than the average (8.3 times the root mean square of CMB fluctuations). This research is aimed at investigating the origin of the CS as the secondary anisotropy CMB fluctuations, specifically the integrated Sachs-Wolfe (ISW) effect by cosmic voids. The Hamaus, Sutter, and Wendelt void profile is used in the ISW calculation. The calculation shows that the radius of void rv, the central density contrast δc, and the redshift z are needed to be −1 . Mpc h , −0.5 (specific value), and . , respectively. The void profile can fit the data�ퟑퟎ quite well except for the positive fluctuation�ퟎ ퟔퟎ region in the CS and the probability �ퟐퟎ �ퟎ ퟏퟑ ofퟏퟗퟎ finding such a void is only 10−17. ퟎ ퟒퟓ Keywords: CMB, cosmic voids, ISW effect Introduction The cosmic microwave background (CMB) with very small Gaussian fluctuations. The radiation is the earliest electromagnetic signal root mean square (RMS) of the fluctuations is of the Universe that can be observed.