The Collected Teachings of AJAHNCHAH

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

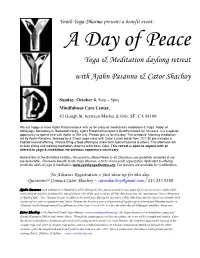

Yoga & Meditation Daylong Retreat with Ajahn Pasanno & Cator Shachoy

Youth Yoga Dharma presents a benefit event: A Day of Peace Yoga & Meditation daylong retreat with Ajahn Pasanno & Cator Shachoy Sunday, October 4, 9am – 5pm Mindfulness Care Center, 42 Gough St, between Market & Otis, SF, CA 94109 We are happy to have Ajahn Pasanno back with us for a day of mindfulness meditation & Yoga. Abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery in Redwood Valley, Ajahn Pasanno has been a Buddhist monk for 40 years. It is a special opportunity to spend time with Ajahn in The City. Please join us for this day! The schedule: Morning meditation led by Ajahn Pasanno, followed by a 2-hour yoga class with Cator. Lunch break from 12-1:30 pm includes a traditional meal offering. Please bring a food offering to share with Ajahn Pasanno & others. The afternoon will include sitting and walking meditation, dharma reflections, Q&A. This retreat is open to anyone with an interest in yoga & meditation. No previous experience necessary. Retreat fee: In the Buddhist tradition, this event is offered freely to all. Donations are gratefully accepted & are tax-deductible. Proceeds benefit Youth Yoga Dharma, a 501c-3 non-profit organization dedicated to offering youth the skills of yoga & meditation: www.youthyogadharma.org. Tax receipts are available for contributions. No Advance Registration – Just show up for this day. Questions?? Contact Cator Shachoy – [email protected] / 415.235.9380 Ajahn Pasanno took ordination in Thailand in 1974. During his first year as a monk he was taken by his teacher to meet Ajahn Chah, with whom he asked to be allowed to stay and train. -

River Dhamma

Arrow River Forest Hermitage Spring/Summer 2019 RIVER DHAMMA ARROW RIVER FRONT PAGE NEWS Abbots’ Meeting at the Hermitage About the Thai Forest Tradition The Thai Forest tradition is the branch of Arrow River is honoured to be hosting the 2019 Theravāda Buddhism in Thailand that most strictly North American Abbots’ Meeting from September upholds the original monastic rules of discipline 4 to 11. Seven abbots from monasteries in the laid down by the Buddha. The Forest tradition also Ajahn Chah tradition from Canada and the United most strongly emphasizes meditative practice and States will gather for fellowship and to enjoy the the realization of enlightenment as the focus of peace and solitude of the Hermitage. monastic life. Forest monasteries are primarily Needless to say, this event is grand undertaking oriented around practicing the Buddha’s path of for Arrow River. We have made a plan of priorities contemplative insight, including living a life of to complete to get things ship-shape for the visit. discipline, renunciation, and meditation in order to As we are an organization with a tight budget and fully realize the inner truth and peace taught by a small group of volunteers, we are looking for the Buddha. Living a life of austerity allows forest some help. monastics to simplify and refine the mind. This refinement allows them to clearly and directly Here’s what you can do: explore the fundamental causes of suffering within 1. Come out to Arrow River to help with their heart and to inwardly cultivate the path preparations. There will be scheduled work leading toward freedom from suffering and days, but you can also come on your own supreme happiness. -

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

The Island, the Refuge, the Beyond

T H E I S L A N D AN ANTHOLOGY OF THE BUDDHA’S TEACHINGS ON NIBBANA Ajahn Pasanno & Ajahn Amaro T H E I S L A N D An Anthology of the Buddha’s Teachings on Nibbæna Edited and with Commentary by Ajahn Pasanno & Ajahn Amaro Abhayagiri Monastic Foundation It is the Unformed, the Unconditioned, the End, the Truth, the Other Shore, the Subtle, the Everlasting, the Invisible, the Undiversified, Peace, the Deathless, the Blest, Safety, the Wonderful, the Marvellous, Nibbæna, Purity, Freedom, the Island, the Refuge, the Beyond. ~ S 43.1-44 Having nothing, clinging to nothing: that is the Island, there is no other; that is Nibbæna, I tell you, the total ending of ageing and death. ~ SN 1094 This book has been sponsored for free distribution SABBADÆNAM DHAMMADÆNAM JINÆTI The Gift of Dhamma Excels All Other Gifts © 2009 Abhayagiri Monastic Foundation 16201 Tomki Road Redwood Valley, CA 95470 USA www.abhayagiri.org Web edition, released June 13, 2009 VI CONTENTS Prefaces / VIII Introduction by Ajahn Sumedho / XIII Acknowledgements / XVII Dedication /XXII SEEDS: NAMES AND SYMBOLS 1 What is it? / 25 2 Fire, Heat and Coolness / 39 THE TERRAIN 3 This and That, and Other Things / 55 4 “All That is Conditioned…” / 66 5 “To Be, or Not to Be” – Is That the Question? / 85 6 Atammayatæ: “Not Made of That” / 110 7 Attending to the Deathless / 123 8 Unsupported and Unsupportive Consciousness / 131 9 The Unconditioned and Non-locality / 155 10 The Unapprehendability of the Enlightened / 164 11 “‘Reappears’ Does Not Apply…” / 180 12 Knowing, Emptiness and the -

Intuitive Awareness

IntuitiveIntuitive AAwarenesswareness Ajahn Sumedho HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Intuitive Awareness Ajahn Sumedho Intuitive Awareness 1 Dedications Dedicated to Ajahn Sumedho on his seventieth birthday with love and respect. In loving memory of my parents, David and Sheila Miles. And my son Riccardo Cattabiani, with gratitude for everything they have taught me. With gratitude for the life of Sritorn Hagyard. May she know the peace of Nirvana. Intuitive Awareness Ajahn Sumedho Amaravati Buddhist Monastery Awareness is your refuge: Awareness of the changingness of feelings, of attitudes, of moods, of material change and emotional change: Stay with that, because it’s a refuge that is indestructible. It’s not something that changes. It’s a refuge you can trust in. This refuge is not something that you create. It’s not a creation. It’s not an ideal. It’s very practical and very simple, but easily overlooked or not noticed. When you’re mindful, you’re beginning to notice, it’s like this. For Free Distrubution Publications from Amaravati are for free distribution. In most cases, this is made possible by individuals or groups making donations specifically for the publication of Buddhist teachings, to be made freely available to the public. Amaravati Publications Amaravati Buddhist Monastery Great Gaddesden Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire HP1 3BZ England ISBN 1 870205 17 0 © Amaravati Publications 2004 www.amaravati.org www.forestsangha.org www.dhammatalks.org -

Mahasi Sayadaw's Revolution

Deep Dive into Vipassana Copyright © 2020 Lion’s Roar Foundation, except where noted. All rights reserved. Lion’s Roar is an independent non-profit whose mission is to communicate Buddhist wisdom and practices in order to benefit people’s lives, and to support the development of Buddhism in the modern world. Projects of Lion’s Roar include Lion’s Roar magazine, Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly, lionsroar.com, and Lion’s Roar Special Editions and Online Learning. Theravada, which means “Way of the Elders,” is the earliest form of institutionalized Buddhism. It’s a style based primarily on talks the Buddha gave during his forty-six years of teaching. These talks were memorized and recited (before the internet, people could still do that) until they were finally written down a few hundred years later in Sri Lanka, where Theravada still dominates – and where there is also superb surf. In the US, Theravada mostly man- ifests through the teaching of Vipassana, particularly its popular meditation technique, mindfulness, the awareness of what is hap- pening now—thoughts, feelings, sensations—without judgment or attachment. Just as surfing is larger than, say, Kelly Slater, Theravada is larger than mindfulness. It’s a vast system of ethics and philoso- phies. That said, the essence of Theravada is using mindfulness to explore the Buddha’s first teaching, the Four Noble Truths, which go something like this: 1. Life is stressful. 2. Our constant desires make it stressful. 3. Freedom is possible. 4. Living compassionately and mindfully is the way to attain this freedom. 3 DEEP DIVE INTO VIPASSANA LIONSROAR.COM INTRODUCTION About those “constant desires”: Theravada practitioners don’t try to stop desire cold turkey. -

Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements

Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Buddhist Revivalist Movements Alan Robert Lopez Buddhist Revivalist Movements Comparing Zen Buddhism and the Thai Forest Movement Alan Robert Lopez Chiang Mai , Thailand ISBN 978-1-137-54349-3 ISBN 978-1-137-54086-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-54086-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956808 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specifi c statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. Cover image © Nickolay Khoroshkov / Alamy Stock Photo Printed on acid-free paper This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by Springer Nature The registered company is Nature America Inc. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

Venerable Acariya Mun Bhuridatta Thera

A SpiritualA Spiritual BiographyBiography This book is a gift of Dhamma and printed for free distribution only! Venerable âcariya Mun Bhåridatta Thera A Spiritual Biography by âcariya Mahà Boowa ¥àõasampanno Translated from the Thai by Bhikkhu Dick Sãlaratano Forest Dhamma of Wat Pa Baan Taad THIS BOOK MUST BE GIVEN AWAY FREE AND MUST NOT BE SOLD Copyright 2003 © by Venerable âcariya Mahà Boowa ¥àõasampanno This book is a free gift of Dhamma, and may not be offered for sale, for as the Venerable âcariya Mahà Boowa ¥àõasampanno has said, “Dhamma has a value beyond all wealth and should not be sold like goods in a market place.” Reproduction of this book, in whole or in part, by any means, for sale or material gain is prohibited. Permission to reprint in whole or in part for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma is hereby granted, and no further permission need be obtained. But for the electronic reproduction or distribution of this book, permission must first be obtained. Inquiries may be addressed to: Wat Pa Baan Taad, Baan Taad, Ampher Meuang, Udon Thani, 41000 Thailand Venerable âcariya Mun Bhåridatta Thera: by Venerable âcariya Mahà Boowa ¥àõasampanno. First Edition: 2003 Printed by: Silpa Siam Packaging & Printing Co. Ltd. Official Mahà Boowa Website: www.luangta.com (/english) Contents Translator’s Introduction vii About the Author xvii Author’s Preface 1 1. The Early Years 3 The Prophecy 4 The Sign 7 âcariya Sao Kantasãlo 15 Sarika Cave 24 Sàvaka Arahants 41 2. The Middle Years 55 The Dhutanga Practices 59 A Monk’s Fear of Ghosts 68 Local Customs and Beliefs 78 Hardship and Deprivation 91 Graduated Teaching 101 The Difference is in the Heart 112 The Well-digging Incident 117 An Impeccable Human Being 128 3. -

The Way It Is

The way it is By Ajahn Sumedho 1 Ajahn Sumedho 2 Venerable Ajahn Sumedho is a bhikkhu of the Theravada school of Buddhism, a tradition that prevails in Sri Lanka and S.E. Asia. In this last century, its clear and practical teachings have been well received in the West as a source of understanding and peace that stands up to the rigorous test of our current age. Ajahn Sumedho is himself a Westerner having been born in Seattle, Washington, USA in 1934. He left the States in 1964 and took bhikkhu ordination in Nong Khai, N.E. Thailand in 1967. Soon after this he went to stay with Venerable Ajahn Chah, a Thai meditation master who lived in a forest monastery known as Wat Nong Pah Pong in Ubon Province. Ajahn Chah’s monasteries were renowned for their austerity and emphasis on a simple direct approach to Dhamma practice, and Ajahn Sumedho eventually stayed for ten years in this environment before being invited to take up residence in London by the English Sangha Trust with three other of Ajahn Chah’s Western disciples. The aim of the English Sangha Trust was to establish the proper conditions for the training of bhikkhus in the West. Their London base, the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara, provided a reasonable starting point but the advantages of a more gentle rural environment inclined the Sangha to establishing a forest monastery in Britain. This aim was achieved in 1979, with the acquisition of a ruined house in West Sussex subsequently known as Chithurst Buddhist Monastery or Cittaviveka. -

Dependent Origination: Seeing the Dharma

Dependent Origination: Seeing the Dharma Week Six: Interconnectedness and Interpenetration Experiential Homework Possibilities The experiential homework is essentially the first exercise we practiced in class involving looking for the boundary between oneself and other than self while experiencing seeing. This is the exercise my dissertation subjects were given for my data collection portion of my dissertation research. It relates directly to the transition from the link of nama-rupa to the link of vinnana, and then sankhara, that I spoke about in my talk this week. Just so that you can begin to have some experiential relationship to my research before I present my dissertation in our last session in two weeks, I’m including the exact instructions as they were given to my participants as well as the daily journal questionnaire they were asked to fill out. Exercises like these are meant not as onetime exercises but for repeated application. Your experience of them will often change and deepen if they are applied regularly over an extended period of time. My subjects used this exercise as part of their daily meditation practice for 15 minutes a day over a period of 10 days. Each day they filled out the questionnaire, their answers to which then became a significant part of my data. See below. Suggested Reading “Subtle Energy” This reading is a selection of excerpts from my dissertation Literature Review regarding the topic of subtle energy. See below. Transcendental Dependent Origination by Bhikkhu Bodhi. This is a sutta selection translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi with his commentary. While the ordinary form of Dependent Origination describes the causes and conditions that lead to suffering, in this version, the Buddha also enumerates the chain of causes and conditions that lead to the end of suffering. -

Amaravati Calendar 08

2008 2551 PHOTO AND TEXT CREDITS This 2008 calendar features pictures by a variety of photographers. © Wat Pah Nanachat (Feb, Mar, May, Aug, Oct, Dec); © Amaravati Publications (Apr); © Aruna Publications (Jan, June, Sept); © Khun Tu (July, Nov). Scriptural quotes on each page are English renderings of texts from the Pali Canon. The translations draw on the works from: “A Dhammapada for Contemplation” © Aruna Publications 2006; and texts from Itivuttaka 3.50; Theragatha 1.3 from Thanissaro Bhikkhu © Access to Insight 2005 edition, www.accesstoinsight.org For free distribution. This work may be republished, reformatted, reprinted, and redistributed in any medium. It is the author's wish, however, that any such republication and redistribution be made available to the public on a free and unrestricted basis and that translations and other derivative works be clearly marked as such. Appreciation is expressed to all who have offered assistance with this production. LUNAR OBSERVANCE DAYS These days are devoted to quiet reflection at the monastery. Visitors may come and take the Precepts for the day and join in all or part of the extended evening meditation. The dates for the lunar calendar are determined by traditional methods of calculation, and are not always the same as the precise astronomical occurrences. THE MAJOR FULL-MOON DAYS OF 2008 – 2551/52 Magha Puja March 21 (‘Sangha Day’) Commemorates the spontaneous gathering of 1,250 arahants, to whom the Buddha gave the exhortation on the basis of the discipline (Ovada Patimokkha). Vesakha Puja (Wesak) May 19 (‘Buddha Day’) Commemorates the birth, enlightenment and passing away of the Buddha.